In the late 1950s, a Texas town on the Gulf of Mexico was suffering from a devastating, decade-long drought. But while the wells ran dry, the ocean lapped at the town’s shore, taunting the thirsty residents with its endless supply of undrinkable water. Undrinkable, that is, until President John F. Kennedy stepped in to save the day with the promise of science. The evolving technology of desalination wouldn’t just end droughts: it would give us as much water as we wanted. It would allow us to inhabit otherwise uninhabitable places. It would let us make the deserts bloom. But at what cost?

Credits

Hosts: Alexis Pedrick and Elisabeth Berry Drago

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producers: Rigoberto Hernandez, Alexis Pedrick

Reporter: Rigoberto Hernandez

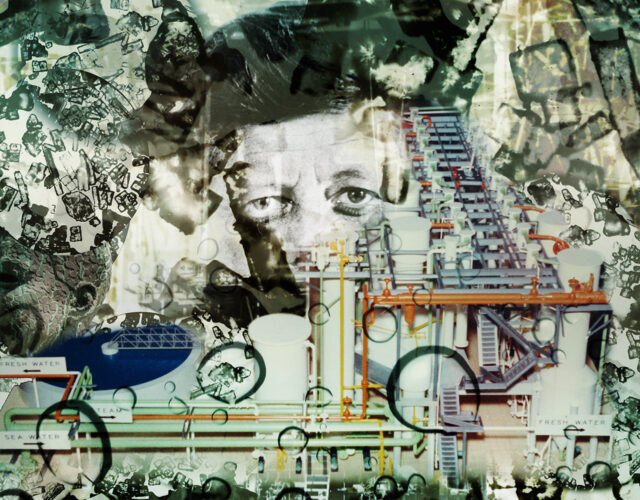

Photo illustration by Jay Muhlin

Music courtesy of the Audio Network.

Research Notes

Barringer, Felicity. “As ‘Yuck Factor’ Subsides, Treated Wastewater Flows from Taps.” New York Times, February 9, 2012.

Burnett, John. “When the Sky Ran Dry.” Texas Monthly, July 2012.

“Countries Who Rely on Desalination.” World Atlas.

Gies, Erica. “Desalination Breakthrough: Saving the Sea from Salt.” Scientific American, June 6, 2016.

“Is Desalination the Future of Drought Relief in California?” PBS NewsHour, October 30, 2015.

Jaehnig, Kenton, and Jacob Roberts. “Nor Any Drop to Drink.” Distillations, November 2018.

Leahy, Stephen, and Katherine Purvis. “Peak Salt: Is the Desalination Dream over for the Gulf States?” Guardian, September 29, 2016.

Madrigal, Alexis. “The Many Failures and Few Successes of Zany Iceberg Towing Schemes.” Atlantic, August 10, 2011.

Miller, Joanna M. “Desalting Plant Opens Amid Surplus.” Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1992.

“President Hails Desalting Plant; He Flips Switch to Dedicate Water Project in Texas.” New York Times, June 22, 1961.

Pulwarty, Roger, John Wiener, and David Ware. “Bite without Bark: How the Socioeconomic Context of the 1950s U.S. Drought Minimized Responses to a Multiyear Extreme Climate Event.” Weather and Climate Extremes 11 (2016): 80–94.

Rivard, Ry. “The Desalination Plant Is Finished but the Debate over It Isn’t.” Voice of San Diego, August 30, 2016.

“San Diego’s Oversupply of Water Reaches a New, Absurd Level.” Voice of San Diego, February 2, 2016.

“With the Drought Waning, the Future of Desalination Is Murkier.” Voice of San Diego, June 5, 2017.

“The Year in San Diego Water Wars.” Voice of San Diego, December 29, 2015.

Simon, Matt. “Desalination Is Booming. But What about All That Toxic Brine.” Wired, January, 14, 2019.

“The 1976–1977 California Drought: A Review.” California Department of Water Resources, May 1978.

Voutchkov, Nikolay. “Desalination—Past, Present and Future.” International Water Association, August 17, 2016.

Video Archive

“The California Drought 1976–77: A Two Year History” (video). California Department of Water Resources.

“The MacNeil/Lehrer Report; Drought in the West.” Broadcast on February 11, 1977. National Records and Archives Administration, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (WGBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA, and Washington, DC, accessed March 19, 2019.

“White House Today (1961).” Lake Jackson Historical Museum, 1961. Texas Archive of the Moving Image.

Transcript

Making the Deserts Bloom

Mother nature creates a more serious situation in Texas and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, New Mexico and Colorado. A six-month drought kills off cattle and ruins crop. The critical need for water makes it necessary for the farmers to truck the precious liquid to their herds.

Empty stock pens testified to the Dreadful loss already sustained by the ranchers the last rain a little over 1 inch fell here in September further setbacks. Come next month when calves are sold at a loss.

Alexis: Hello and welcome to Distillations. A podcast powered by the Science History Institute. I’m Alexis Pedrick.

Lisa: And I’m Lisa Berry Drago.

Alexis: Distillations is a show where we take a deep-dive into a moment of science-related history in order to shed some light on the present. And the team that produces it? Well, we’re all nerds about the history of science which is, to be clear, a huge and ever expanding topic.

Lisa: And we’re all passionate about different aspects of it. So behind the scenes every month, we’re wrangling with topics and research with the goal of bringing you a story that makes you look at the world in a different way.

Alexis: There’s myself and Lisa, your hosts. Our senior producer Mariel Carr

Mariel: Hey guys.

Alexis: Who you might remember from our opioids story, and our other producer Rigo Hernandez.

Rigo: Hello.

Lisa: today’s story actually comes from Rigo and some reporting he did in his hometown in California.

Alexis: He’s going to pick up this story later in the episode so you’ll hear from him, and get to know why he is so passionate about this topic.

Lisa: And what’s that topic? Well, today our story today starts in 1950s Texas, where a terrible drought was taking place and science—actually almost science fiction—came to save the day. Kind of.

Alexis: The story of how Texas responded to the really desperate situation of not having enough water, tells us a lot about what we think science should do for us and the role we think it should play in our lives.

Alexis: Chapter One: The Tragedy of the Commons

Alexis: Between 1950 and 1960 half of Texas’s farming industry vanished. And in a small city on the gulf coast, called Freeport, the drought was hitting especially hard. So hard that rationing prevented people from watering their plants, washing their cars, or running their “evaporative coolers.”

Lisa: And we should note that in southeastern Texas evaporative coolers were not just for fun.

Alexis: Like most of Texas, Freeport got its drinking water from the Brazos River. Which cuts diagonally across much of the state before emptying into the Gulf of Mexico—right next to Freeport.

Jacob Roberts: So by the time this River reaches Freeport, which is again at the very end of the river. The flow has slowed down there’s less water total and they just can’t really rely on it anymore. Because everybody—it’s kind of the tragedy of the commons once there’s a need for water. Everybody just grabs as much as they can without worrying about who’s downstream.

Alexis: That’s Jacob Roberts. He’s a writer for Distillations magazine and he co-wrote a story about the history of one of our” scientific solutions “to drought with Kenton Jaehnig.

Jaehnig: and I am the processing archivist here that the Science History of Science History Institute.

Lisa: By 1957 Freeport was eight years into a decade-long drought. Some farmers had resorted to feeding their animals prickly pear or molasses to keep them alive. The US government was issuing federal food commodities to more than 100,000 people. Of 254 Texas counties, 244 were considered disaster areas. And Freeport was one of them.

Roberts: Their reservoirs were very low for about a decade. They had water rationing, people’s lawns completely dried up. Everything looked kind of dead. They needed water now.

Alexis: Throughout the drought years the salty waters of the Gulf of Mexico lapped at Freeport’s shore, taunting the thirsty town with its undrinkable water. But some people looked out at the sea and wondered, what if they could make that undrinkable seawater… drinkable?

Lisa: On January 13, 1957, four hundred miles from Freeport, in the city of San Angelo Texas, President Dwight Eisenhower gave a speech that his administration would do whatever they could to alleviate the suffering from the drought.

Alexis: But it wouldn’t be Eisenhower who’d deliver Freeport from its drought. That honor belonged to a new president, one who was dealing with increasingly complex foreign relations

and needed a win: John F. Kennedy. But he didn’t do it alone. JFK was concerned about water in Texas because his Vice President, Lyndon B. Johnson, made sure he was concerned about it.

Kennedy: It’s a matter of the greatest interest to the vice president who living as he does in the state of Texas has seen throughout his life how important it is. That the freshwater be secured.

Lisa: Water security had been a priority for LBJ for a while. As a senator he worked on a bill to build dams that saved fresh water. When he was the senate whip, Congress passed the Saline Water Act in 1952.

Alexis: All that drought going on? It hadn’t gone unnoticed. The Saline Water Act was basically a research program to figure out the best way to convert seawater into drinkable water. Which begs a very basic question.

Lisa: Right. Why can’t we drink the ocean?

Roberts: it’s very ironic that we’re surrounded by all this water. The world is made up of about 70% water and only a tiny percentage of that is freshwater. That humans can drink and even a smaller percentage of that. Is accessible so most of it’s locked up in glaciers or it’s far underground. We can’t access it. For all of human history people have been thinking what’s up with that. Why can’t we just drink the ocean?

Alexis: The answer is actually pretty simple: you can’t drink the ocean because it’ll kill you. If you drink enough of it. Sea water is made up of H2O, yes, but also a lot of salt. Too much salt for the human body to process. When you drink it, your body has to work really hard to flush out that salt, and you end up peeing more water than you drink. And then you dehydrate. And then you die.

Lisa: But humans don’t really like limitations like this. If there’s an ocean full of water we want the option of drinking it. So we created a work-around: desalination. Getting the salt out of saltwater.

Alexis: In 1955 Congress establishes the “Office of Saline Water” and within a few years they came up with a plan to create five pilot desalination plants around the United States.

Roberts: Each one was planned to use a different type of Technology because they didn’t know what would be the best way to you know, create desalinated water. So one plant used freezing technology, which was essentially what it sounds like you would freeze the water and because the density of water and salt is different it would have essentially separate the water from the salt. So you just scoop the ice off the top. And then melt it and it would be fresh water and the salt will be trapped in the bottom.

Lisa: There’s also an evaporation method which is essentially boiling the water and then capturing the steam. This was the method used by the first desalination plant in the United States, in Freeport, Texas, when it opened in 1961.

Alexis: The Freeport plant used the evaporation technique because of the man who led the project; a chemical engineer named Walter L. Badger. He was an expert on chemical evaporators. And he made money by selling the solids he’d extracted from liquids—things like salt and chlorine.

Roberts: and the focus and didn’t become until later on actually keeping the water that they were boiling off. So at the beginning they were valuing the solids that were in the water and then later they realized that the real value was actually the pure water itself.

Lisa: Badger was a character. In addition to being a chemical engineer he was a professor, and he had a reputation for being tough on students. He’d call them to the front of the room and blow smoke in their faces while they drew evaporator designs on the chalkboard. Sweet guy. Here’s Kenton Jaehnig, processing archivist at the Science History Institute.

Jaehnig: he was pushing them. He was trying to see if he’s trying to get them to do their job. Well wanted things he tried to get across to the students was that you know in the in the chemical industry, you know that the chemical companies expect the results from their employees.

Alexis: And Congress was relying on Badger for results. But he was undaunted by the task and by the promise of desalination.

Roberts: Badger just make comments like. I’ve been working in this field for about 50 years. I think I know a thing or two about evaporators just was clearly had a little bit of an ego and I think that the congressmen who were listening to him definitely ate it up.

Alexis: So the project proceeds, the plant is built and it really was a marvel of engineering. There’s a virtually infinite supply of water in the ocean and now we can control it. It’s the ultimate triumph of science over nature. President John F. Kennedy hailed it as a pivotal American scientific achievement.

Kennedy: This is a work which in many ways is a more important than any other scientific Enterprise In which this country is now engaged.

Lisa: Everyone is over the moon. We will in fact, get to the moon in about eight years, but for the time being there are plenty of jobs, the plant is about to bring much needed water security to the region. And remember when we said Kennedy was dealing with some complex foreign relations problems and needed a win?

Alexis: We were talking about the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba and the Berlin Crisis that split the German capital.

Jaehnig: And also there are other thing that was going on during this time was where the beginnings of the Space Race and they’re the headers and there are some concern that America at that time was falling behind in the realm of science. Basically he needs some good news.

Alexis: Some good scientific news. So on the day the Freeport desalination plant opens in 1961 Kennedy was actually there. Kind of. What happens next is a combination of TV magic and clever staging.

Roberts: So Kennedy is sitting in the Oval Office. He’s got the cameras on him. and he’s giving this speech which is being broadcast directly through the microphones to the crowds at Freeport, on the other side of the country basically.

Kennedy: I’m sure that before this decade is out that we will see more and more evidence of man’s ability at an economic rate to secure fresh water from salt water. And when that day comes then we will literally see the deserts bloom.

Roberts: here he was saying that we’re going to harness the ocean. We’re going to turn deserts into farmland. We’re going to bring men and women out of poverty and it’s all because of Science.

Alexis: And he reaches over and pushes this shiny black button, that kinds of looks like a telegraph. And there’s a wire sticking out of it, but you can’t tell if it’s actually connected to anything, and then he leans over and says:

Kennedy: I hope it works.

Alexis: I hope it works. As in, I hope this moment of cinema magic and staging doesn’t bomb while I’m live on national television. But also, maybe, I hope this thing I’ve played up as saving us actually saves us…?

Roberts: and then the camera cuts to back and Freeport where a spigot opens up in water fresh water gushes out into a tank and children run up with paper cups and the crowd is like smiling families and mothers and you know reporters and so it’s implying that Kennedy somehow has started up this whole plant.

Alexis: And then it’s over.

Lisa: Desalination has solved everything.

Alexis: But of course it’s more complicated than that. Because this wouldn’t be Distillations if we didn’t take that pretty picture and mess it up a little bit.

Lisa: JFK might have had a win in Texas, but droughts would continue to afflict the country, and things would get messy. And messier. Especially in California.

Alexis: So here’s where we are bringing in our producer Rigo Hernandez. Like the rest of us, Rigo likes to complicate things and because he grew up in San Diego, and water scarcity has been on his mind for most of his life.

Lisa: Chapter Two: Jerry Brown, AKA, Governor Moonbeam

Lehrer: Drought, Drought of record-setting proportions in 13 States from California to Kansas North Dakota to Colorado water rationing for business and industry as well as private use is already in effect in some areas. And weather forecasters say it’s going to all get worse before it gets better.

Rigo: That’s Jim Lehrer, on PBS in 1977. In 1976, California got hit with the worst drought in state history. It might not have lasted as long as the decade-long Texas one—it actually only lasted two years—but the stakes were higher. California is the most populous state in the country. And it grows most of our fruits and vegetables.

Lehrer: Other Industries dependent on water are suffering a car wash operator in Mill Valley tried drilling for his own water to save his business, but didn’t have any luck. The laundry business has been struggling to stay alive by cutting back on its processes and trying to reduce. The number of customers such individual struggles are only the beginning according to many who see the drought and its ramifications spreading through every sector of the California economy and lifestyle before it’s over.

Rigo: California’s governor at the time was Jerry Brown. AKA Governer Moonbeam, a nickname he earned because of his idealistic and non-traditional policies. Here he is on PBS in 1977.

Jerry Brown: We are subject to limits as people were 2,000 years ago and we can harness nature to some extent but the we haven’t learned how to control it yet.

Rigo: If this sounds familiar to you you’re not alone. Apparently politicians really like talking about harnessing the power of nature.

Jerry Brown: and I hope that not only the secretary of agriculture, but those other people in Washington will provide some funds and some leadership. In such projects as using the ocean of which certainly the planet is well-endowed with.

Rigo: The agriculture industry lost a billion dollars during the two-year drought. But for all his talk about harnessing nature and drinking the ocean, Jerry Brown didn’t build a desalination plant. He also said this on PBS:

Jerry Brown: And there is a certain arrogance of power that lays waste the basic resources of our land that we’re going to have to change we have to realize the we’re on this planet just like all the other species and I think there’s been a certain degree of pride and arrogance that is not recognized that.

Rigo: Brown created what I like to think of as a water police force. And residents were asked to cut their water use by 10 percent. People who didn’t were charged extra. In the end Southern California cut its water use by 15 percent, exceeding the goal. It was the first time the state got serious about water conservation. And then rains returned in 1978. But the state warned people not to fall into a “false sense of security.” They started airing ads like this one:

DPW: When it rains in California, remember that our summers are long, hot and dry. Remember that California survives on the water it saves. On water stored and reservoirs and groundwater basins. And remember that the California department of water resources wants you to save water all year long. Save every one last drop, it saves energy too.

Rigo: Jerry Brown was on to something. Because as politically sexy as JFK made building desalination plants seem, they’re actually NOT the best solution to drought. But we keep building them anyway.

Alexis: Chapter Three: A Brief History of Desalination and its Complications

Rigo: The ocean has been taunting thirsty people for a long time. It bothered Aristotle back in 340 BCE. And he came up with a desalination method using evaporation. It was essentially the same method Walter Badger would later use at the Freeport, Texas plant. The ancient Greeks and Romans also dealt with water shortages. But instead of desalination they built aqueducts that carried fresh water from lakes and rivers. Here’s Jacob Roberts again:

Roberts: Even at the very beginning it was clear that doing a massive engineering project like building an aqueduct, which is really incredible. And obviously they’ve lasted Through the Ages and can still see them today to take advantage of existing sources of freshwater was just way easier and more energy efficient and less time-consuming then to extract the fresh water from the ocean.

Rigo: In modern history the first examples of people trying to drink the sea were people LIVING on the sea. People on boats. People with no other water at hand. People like sailors and explorers. During World War II, battleships and submarines on both sides used small seawater purification machines to make sure their crews stayed hydrated. Later those same machines would move off boats and on to islands. Like the Dutch colony of Aruba, which has virtually no fresh water. It’s bone dry and surrounded by salty water. It wouldn’t be such an appealing place to colonize if it weren’t for all of its oil. In the 1930s through the 50s the Dutch made enough money from Aruba’s oil industry that they could buy their way out of the fact that there was no drinking water on the island. They could use that money to pay for desalination. And they wouldn’t be the only country that would turn oil into water.

Roberts: The end result was basically that they created sort of an oasis sort of in the middle of a place where life really has no right to exist. I mean this was an island that

had very few vegetation and animals on it just because it didn’t really get much rain and the Dutch were basically able to create a city, a small city of workers out of nothing.

Rigo: Desalination only made sense on Aruba because of all their oil money. Today Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Kuwait are in the same boat. And that’s because one of the challenges of desalination is that it’s really expensive.

Alexis: Remember that tidy Freeport, Texas story we neatly wrapped up for you a little while ago? Well, we’re back to ruin it. You’re welcome.

Lisa: So Freeport’s plant was the first industrial-sized, desalination plant that was ever built in the United States. And it was a big accomplishment. But it ultimately closed and was forgotten. Here’s Jacob Roberts again, telling us about the shortcomings of Walter Badger’s plan.

Roberts: The price of water at the time was about 35 cents per thousand gallons that was sort of like the standard price that you would pay for water in 1961 America. Now even though Badger brought the price down a lot with his design. His desalinated water was still costing about one dollar and 25 cents per thousand gallons, which is you know, that a good and astronomically higher amount compared to regular water that you could just grab from a stream or river.

Lisa: So it was expensive. There also wasn’t enough of it.

Roberts: it was supposed to create an output of about a million gallons of fresh water per day. So essentially this plant was a test case to see can we provide the water for an entire city with desalination plant?

Alexis: I know that a million gallons of water a day sounds like a lot of water.

Roberts: but it was still only a percentage of their water remember because even a million gallons a day. Is not enough water for 14,000 people to live off of.

Lisa: But there was another reason why the plant closed.

Jaehnig: the other thing that happened at Freeport was that I thought that the drop

Roberts: just as these plants were built in response to a drought happening. They were shut down in response to a drought ending.

Lisa: Chapter Four: How should science save us from drought?

Rivard: I’m fascinated by water. I think it’s the next Frontier. I mean everybody said, you know, we used to fight wars over oil now, we’re going to fight them over water.

Rigo: This is Ry Rivard. He writes about water and energy for the voice of San Diego—an investigative news outlet. I asked him if desalination was the answer to drought.

Rivard: Some water officials that I’ve talked to say that desalination is a perfectly logical solution to droughts and a perfectly logical insurance policy. But there is a sequence that I think a good number of people who would concede desalination can be necessary would say needs to happen before you do desalination. The first is you make sure that everybody’s conserving as much as they possibly can. So you drive down demand as much as you can without hurting the economy.

Rigo: California’s actually gotten pretty good at that. Remember, after the 1976-1977 drought Southern California cut its water use by 15 percent.

Rivard: And the second thing you do. And not because it’s much cheaper, but just because it’s kind of more efficient in some ways is you recycle waste water.

Lisa: You recycle waste water. Ry’s talking about capturing and re-using—as in drinking—the water you flush down the toilet. Recycling waste water takes as much energy as desalination does. They both have a high carbon footprint. But it doesn’t create a problematic byproduct: brine.

Alexis: Right. Because if you’ve been wondering what happens to all the salt that gets extracted by desalination, It GETS DUMPED BACK IN THE OCEAN. And there’s a lot of it. And it’s making oceans saltier. Which is making desalinating ocean water harder. It’s also affecting marine life– and probably not in good ways. But we haven’t studied it enough to know exactly how. Recycling waste water is a better solution than desalination. There’s only one problem. The yuck factor.

Rivard: Well in San Diego, we had a rough history with recycled Wastewater.

We have an update to a story that might disgust you. The city council voted to move ahead with a toilet to tap plan –yummy—which will purify 50 million of gallons of recycled water a day. And you know where it’s recycled from? The toilet.

Now that’s poopy water.

Lisa: Calling recycled waste water “poopy water” did not help sell it as a solution. And when it comes down to it, it seems like we don’t actually usually want the best solution. We want the most appealing solution. Science only offers up the solutions that the culture can bear. And the culture of San Diego could not bear poopy—I mean recycled waste—water.

Rivard: It got branded as toilet to tap, and that killed this project in the city of San Diego for quite a while. A number of years.

Rigo: Los Angeles got a waste-water purification plant up and running but there was significant enough pushback that the water ended up only being used for irrigation. Even Ry doesn’t want to use that term “toilet to tap” anymore because he says it’s unfair.

Rivard: It’s become verboten in pro water recycling circles. And I think that reputation has worn off people are. We’re open to toilet to tap which we’re not supposed to use that phrase.

Rigo: San Diego revived the program in the early 2010s. The new ambitious goal is that treated waste water will provide one third of San Diegans drinking water. But the stakes are high for the city to get it right.

Rivard: There’s this question of if an agency takes on doing water Recycling and they screw it up they would destroy. Water recycling for a generation probably because if if you get fecal material in your water supply because you didn’t get the process, right? You can’t do a water recycling plan anymore and L.A. or Santa Clara or wherever else they want to do it. It just kills it for Generation because they’ll say We’ll look at those idiots in San Diego and what they did, and we don’t want that to happen here. So you have to be very careful doing Wastewater Recycling and so if you just skip ahead and do desalle you spare yourself the headache and you know, it might be a nicer room ribbon cutting.

Rivard: There’s a sort of sexiness to desalination, you know, everybody that build the desalination plant can say, you know, we built the largest desalination facility in the Western Hemisphere and they don’t have to deal with the stigma of wastewater recycling.

Alexis: Like we said, the scientific solutions put in practice are the ones that the culture can bear. And that’s not nothing. There are huge mental hurdles to making waste water purification work. We don’t just need a science solution, we need a social science solution to help people deal with these hang-ups.

Lisa: The mental equation seems like it goes something like this: Desalination equals conquering nature. If we can do it it means we’re smart, and strong. Conserving water equals depriving ourselves, and people don’t like depriving themselves. And waste water recycling equals drinking our own poop. It means we’re gross, and makes us feel like we deserve more. And I’m not saying any of this is true. It’s all false. But the feelings are real.

Alexis: Chapter Five: Alexis is Skeptical.

Alexis: Ok. Rigo, I gotta be honest. I don’t buy it, all. Poopy water has the same carbon footprint as desal, I mean sure it doesn’t leave brine, but why can’t we choose the less gross option? Why can’t we just choose desalination?

Rigo: Bascially poopy water, and I’m laughing because I don’t even like to use that term poopy water, but basically recycled water is a more sustainable and there are two reasons why. One, is the obvious one. You don’t have the biproduct of brine. And the second one is that all that recycled water that you have, you don’t have to use it for drinking. You can actually give it to the

farmers for irrigation so that they stop using ground water—or water from wells—and that frees up all the other water for us to for human consumption only.

Alexis: Okay I get it, so poopy is sort of like secret conservation.

Rigo: Exactly. And there’s another benefit, which is that if you’re landlocked you don’t need the ocean, you can do recycled water there, you have the supplies within your sewers. Look who’s doing desal, it’s places on the ocean.

Alexis: So, I follow that, but, I get it, desal is an imperfect solution, but there are lots of things that are imperfect solutions. Why are we so concerned about this one?

Rigo: Here’s the thing. Now that water is becoming increasingly a commodity, it seems like the direction we’re heading is that only the rich will be able to afford this water. If the whole Narrative of like who gets to have water is that only the rich will be able to have it and then the poor are going to suffer then desalination gives us a glimpse into what the future might look like: only the rich will be able to afford desalination, and that’s horrifying. I mean, look who’s doing it all rich countries in the Middle East like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates and these wealthy California cities like Santa Barbara. I actually went there and there’s a Ronald Reagan mural at the train station, by the way, just to give you a mental image of the place, and I talk to Sheila Lodge, who was the mayor during the big drought in the 1980s.

Lodge: by the way, I the drought was my fault. I don’t know if you knew that.

Rigo: To be clear, she didn’t actually cause the drought.

Lodge: Oh to have such power so.

Rigo: But she was the person who had to fix it. Santa Barbara is especially vulnerable in droughts because of its geography. If you look at a map it’s basically an island. There are mountains to the north and the ocean to the south. It was cut off from the rest of the state and from reliable water sources. By 1990 they were seriously running out of water. They tried conservation. But it wasn’t enough.

Lodge: When did we really get to considering anything and everything including desalination? It was one proposal to use some tugs to bring a an iceberg down from Alaska. The Proposal didn’t explain how. The melting water would be gotten on sure but…

Rigo: Ultimately they did not drag an iceberg anywhere. But they did build a really expensive desalination plant. Which they were only able to do because Santa Barbara is a wealthy city. It’s not unlike Aruba in the 1930s—when it used its oil money to buy desalinated water.

Alexis: So in this Kevin Costner Water World scenario that you’ve laid out, wealthy people will have all the water they want, but poor people won’t have that option. Is that what you’re saying the problem is?

Rigo: It’s that you can’t look at these places and say, oh great, we’ve figured out what we’re going to do in the future when there will be even more droughts, because 99% of the world, or I don’t know I just came up with that number, but MOST of the world will NOT be able to afford desalination. So instead of us exploring actual sustainable solutions to drought, we’re putting a very expensive band-aid on the problem. And it’s a band-aid that’s actual making the CAUSE of droughts worse for everyone else. It’s using a lot of energy and contributing to climate change.

Alexis: Okay, I’m convinced. One more question and then this interrogation is over, I promise. Will desalination ever get cheaper? Is it just that it’s new technology that’s making it expensive?

Rigo: It’s not going to get cheaper, but regular water is going to get more and more expensive. So it’ll even out. This is the new normal.

Alexis: Chapter Six: What if we don’t even need Desalination?

Rigo: In 2015 the largest Desalination plant in the Western Hemisphere opened in Carlsbad California, outside of San Diego. The plant is across the street from the beach. It’s straight out of a postcard.

> >Ocean sounds<>

Rigo: There are dozens of surfers catching waves just outside of the plant.

Paulson: So we just entered the plant and right now we’re actually walking past our solids handling.

Rigo: The opening of the plant was a huge deal. But, within only a few months millions of gallons of its purified water were dumped into a reservoir. San Diego County had too much water.

Rivard: It’s sort of a crazy thing to think that this was really at the tail end of one of the biggest routes and hundreds of years in California that we would have too much water.

Rigo: So what happened? The first thing to understand is how San Diego gets its water. The majority of it comes from pipes connected to the Colorado River and reservoirs in northern California. And water from these sources has to continually flow to people’s taps.

Rivard: It’s like you have to have electric current flowing through a switch even when it’s off. It has to be sort of on standby. So there’s amount of water flowing through this pipe and we couldn’t stop it.

Rigo: It’s also helpful to understand some of the bureaucracy: an agency called the Metropolitan Water District controls the water in Southern California. And the San Diego water authority doesn’t get along with them. And it didn’t want to rely on them for their water.

Lund: I don’t know if they have a dispute with Metropolitan Water District and they feel they have to do this politically, or if they’ve really done the numbers. So their water security problem might be more political than hydrologic.

Rigo: That’s Jay Lund. He studies CA water issues at the University of California, Davis. At the same time San Diego is building its desal plant, Governor Jerry Brown 2.0 is telling the whole state to conserve water. And they did. And it was working. But San Diego had already signed a THIRTY YEAR contract on their desal plant. They were locked in. Jay Lund says the city would only have needed to conserve five to eight percent more water to stay afloat during in 2015. That’s not a lot. In fact, Jay Lund says that desalination is not really necessary. At all.

Lund: when we’ve done computer models that have even very extreme forms of climate change. We see desalination used very rarely. Because it’s so expensive. You do other things first.

Rigo: He is making a point we’ve already made: if you’re looking for the best economic or scientific solution to drought, desalination is not the answer. But we know that a lot of other things go into these decisions: culture, politics, and not wanting to think about yucky things, like poop water. The yuck factor. And San Diego still has too much water, in fact, right now the dams are overflowing. But that desal plant isn’t going anywhere any time soon.

Rivard: You’re not just going to build a billion dollar facility without some promise that people are going to be buying water from it for the long term.

Rigo: It seems like desalination is here to stay.

Rivard: But you want to keep an eye on it because if we’re counting on this thing and it doesn’t work, then we’re in a lot of trouble.

Alexis: So Rigo, after all of this reporting, all these months of talking to people and doing research, I don’t know, what are some parting words of wisdom? What do you want to leave us with?

Rigo: In doing this story, I was frankly really like surprise. I like I kind of saw it as magic. Like at every plant that I went to in Santa Barbara and in San Diego there was, like, at the end of the tour we I got to drink some of the water, they had a little faucet and like you get to drink the desalinated water and actually I thought that was like really freaking cool ,like, it felt like I was like, this is Magic. Just a few minutes ago this was like in the ocean and now it’s here. And that like felt really cool. I felt like those kids have Freeport who were getting their cups and they were drinking that water that was just in the ocean and that felt really cool. But then when you actually start to think about it it’s and then you actually starts to run through the ramifications and all the stuff that goes into this that’s when you start to realize that this is more complicated. That it’s not that simple and that it may be a cool solution and it might make me giddy to think about its magic, but it doesn’t mean that it’s the most sustainable solution.