Dr. Seaborg Goes to Washington

And then goes back. And then back again. And back again…

And then goes back. And then back again. And back again…

What would it take for a scientist to become a trusted advisor to 10 different U.S. presidents over 50 years? From Harry Truman to Bill Clinton, chemist Glenn T. Seaborg (1912–1999) can claim this honor. Seaborg was considered one of the most accomplished chemists of his day—and with good reason. He led teams that discovered 10 new elements and numerous life-saving radioisotopes. He was architect of the last major realignment of the periodic table. An element is named for him. He won a Nobel Prize. And just for fun, he transmuted bismuth, the element next to lead on the periodic table, into gold.

Seaborg’s research helped usher the United States into the Atomic Age, and his expertise led to his counsel on everything from scientific education to national policies for the civilian and military use of nuclear energy. Through the Records of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory – Nuclear Division, held in the Science History Institute Archives, we can catch glimpses of Seaborg’s storied career of service to presidents from both sides of the political aisle.

Seaborg began his career on the faculty of the University of California, Berkeley, at the age of 27. In 1940, utilizing Berkeley’s famed 37-inch cyclotron, he and his colleagues discovered a new element by bombarding uranium atoms with alpha particles. That new element was named plutonium.

Plutonium’s ability to fuel both atomic bombs and nuclear reactors made the discovery top-secret until after the war, but his work continued and at the age of 30, he was called upon to be a section head in the Manhattan Project.

Glenn Seaborg greets First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy during a Visit to the Nuclear Development Center in Lynchburg, Virginia.

Seaborg’s first presidential appointment came four years later in 1946, when Truman appointed him to the first General Advisory Committee of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). This impressive group, which included J. Robert Oppenheimer and Enrico Fermi, exerted great influence over the AEC, especially its emerging civilian nuclear power program.

In 1959 President Eisenhower invited Seaborg to serve on the President’s Science Advisory Committee. In this role Seaborg and his colleagues considered a wide variety of topics with an emphasis on military issues. During personal meetings with the president, Seaborg stressed the importance of arms control and a ban on nuclear testing in the atmosphere. He found Eisenhower to be very agreeable on both matters.

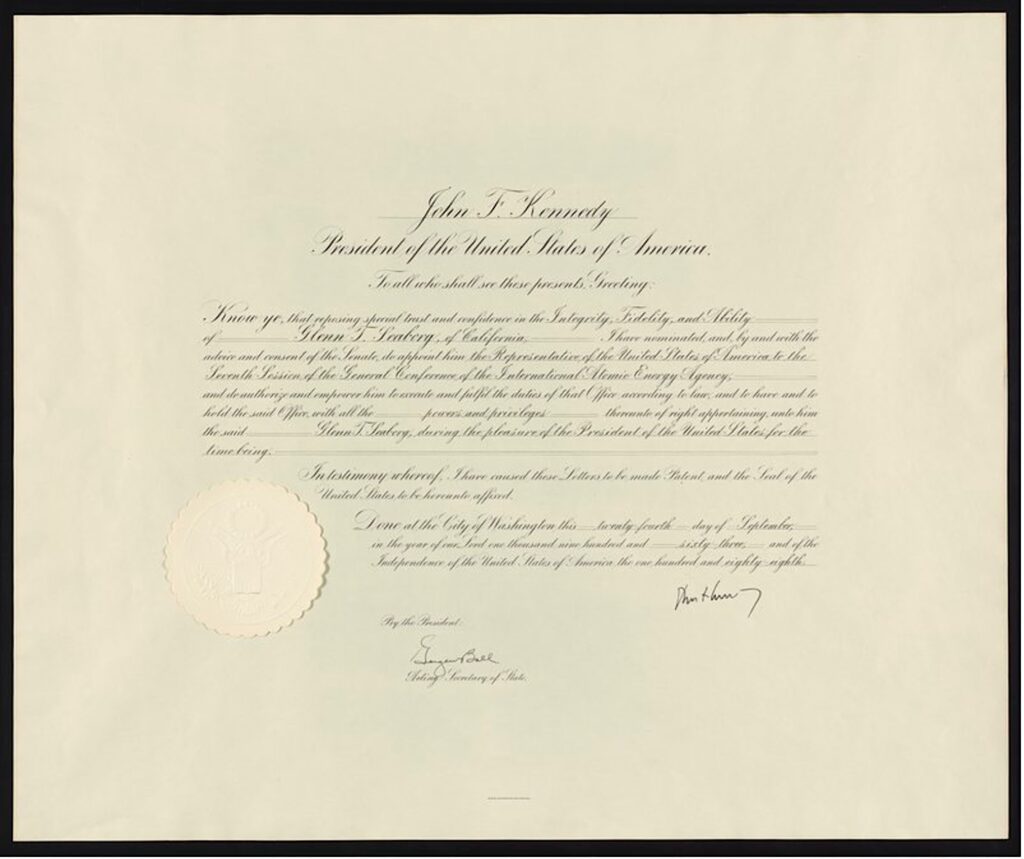

Appointment conferred by John F. Kennedy to Glenn Seaborg as U.S. Representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency, 1963

When President-elect John F. Kennedy phoned Seaborg to request that he accept the position of chairman of the AEC, Seaborg asked how much time he had to decide. “Take your time,” Kennedy said. “You don’t have to let me know until tomorrow morning.” Seaborg accepted the position and remained in the post for more than 10 years.

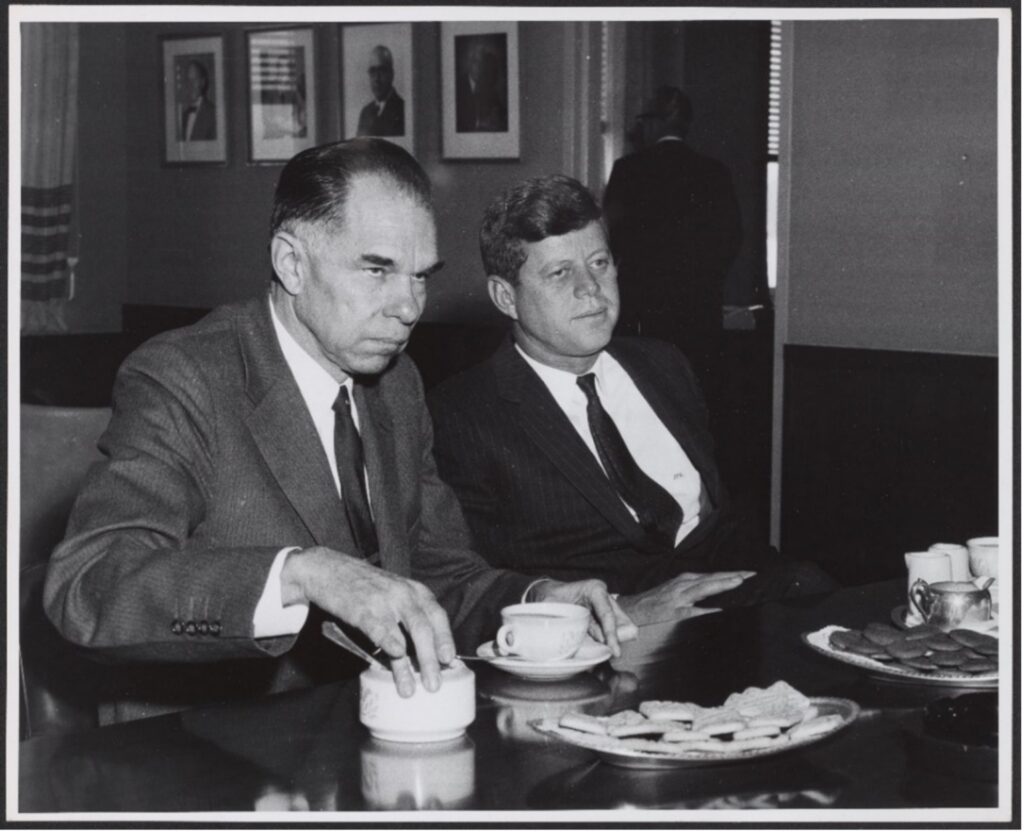

Less than a month after his inauguration, Kennedy visited the AEC’s Germantown, Maryland, headquarters. During morning coffee in Seaborg’s office, the president heard presentations on the fundamentals of atomic energy and nuclear structure. AEC staff then presented on a variety of activities including military weapons, nuclear propulsion, civilian power reactors, and nuclear medicine.

Visit of President John F. Kennedy to the U.S. AEC, February 16, 1961.

Seaborg accompanied the president on tours of various AEC installations including the Radiation Laboratory at Berkeley, the Los Alamos Laboratory, and the Nuclear Weapons Test Site in Nevada. Kennedy’s ability to absorb it all impressed Seaborg who would, in later years, comment that Kennedy was one of the most impressive intellects he’d ever met.

Seaborg and Kennedy at the Nevada Weapons Test Site, 1961.

Kennedy was also the first president to personally present the AEC’s highest honor, the Enrico Fermi Award, at a White House ceremony. The first of these presentations was to theoretical physicist Hans Bethe. When Kennedy concluded the presentation, Seaborg embarrassingly remembered that the $50,000 check that accompanied the award was still in his pocket. He belatedly handed the check to the president, causing the crowd to break out into laughter as photographers captured it all.

Glenn Seaborg and President John F. Kennedy present the AEC’s Enrico Fermi award to Dr. Hans Bethe, December 1, 1961.

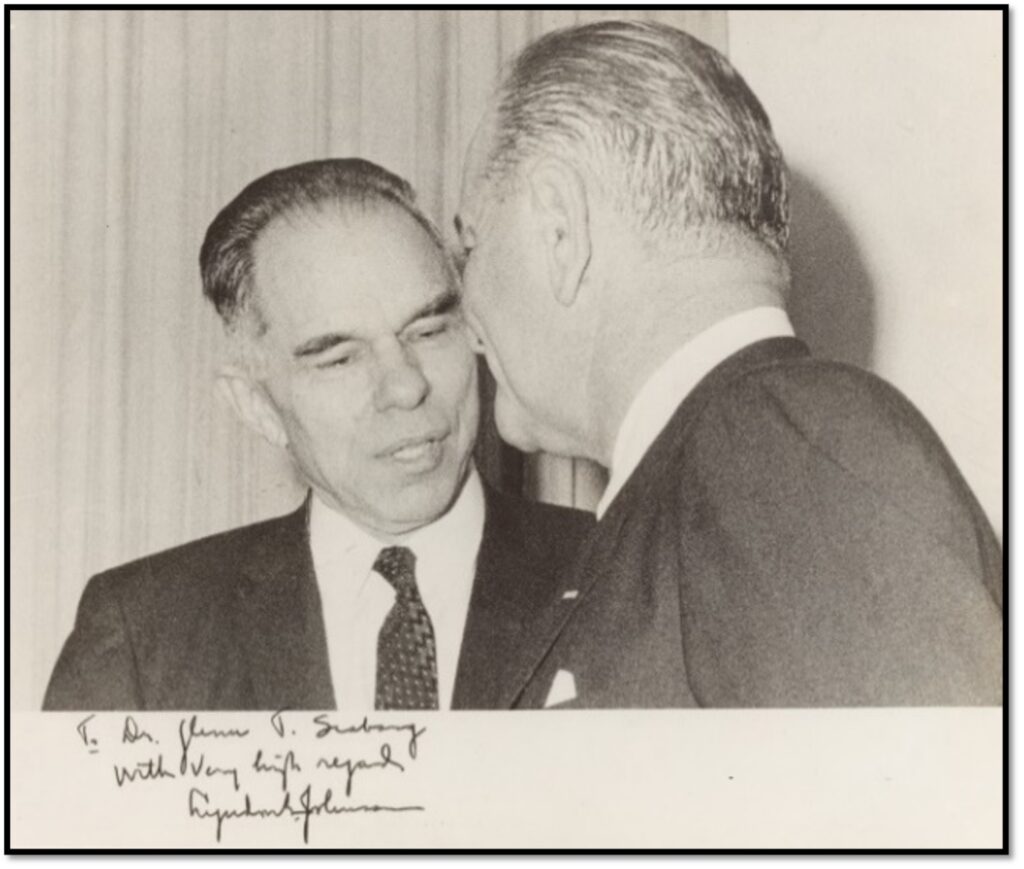

Seaborg remained in his role at the AEC under Lyndon Johnson, who, like Kennedy, frequently sought Seaborg’s advice. Seaborg found Johnson’s personality to be overwhelming, noting that when Johnson wanted advice or information, he wanted it right away.

Glenn Seaborg with President Lyndon B. Johnson, 1968.

Seaborg remembered Johnson’s dedication to the goal of equal opportunity for all Americans. In this respect, Johnson had ordered him to identify a woman and an African American for appointment to the AEC. This resulted in the appointments of Samuel Nabrit (president of Texas Southern University) and later Mary Bunting (president of Radcliffe College) to the commission.

Members of the U.S. AEC (from left): Samuel Nabrit, Wilfred Johnson, Glenn Seaborg, James Ramey, and Gerald Tape, 1966.

When Richard Nixon took office, Seaborg was one of only a few incumbents asked to stay. Seaborg and Nixon first met when both were chosen as the U.S. Junior Chamber of Commerce’s “Ten Outstanding Young Men of 1947.” At the time, Nixon was a congressman and suggested to Seaborg that they should remain in touch and “stick together.” During Seaborg’s first meeting with Nixon in the White House, he reminded him of the photograph they’d taken 20 years earlier and asked the president if he would autograph it, which Nixon gladly did.

Barbara Walker (Miss America 1947) with eight of the Ten Outstanding Young Men of 1947.

Seaborg soon discovered that Nixon operated quite differently from his predecessors. Rather than reporting directly to the president, Seaborg reported to Nixon through a series of intermediaries. He rarely attended Cabinet meetings and soon found himself bypassed completely in all matters related to arms control. Nixon was blunt with Seaborg, stating that he should confine his advice to scientific matters only.

Henry Kissinger, Robert Ellsworth, Patrick Haggerty, President Richard Nixon, Glenn Seaborg, and Lee Dubridge at the White House, 1969.

When Seaborg’s commitment to the AEC ended in 1971, he returned to Berkeley but still served as an informal scientific advisor to U.S. presidents and government bodies for the next three decades. That included Gerald Ford, whom Seaborg first met in the 1960s when Ford was still a member of Congress from Michigan. On one memorable occasion in 1965, the two men snuck away from a formal dinner to watch the NCAA basketball championship game between Seaborg’s alma mater, UCLA, and Ford’s, the University of Michigan. They were joined by Michigan Governor George Romney (father of Mitt), who lamented with Ford over Michigan’s 91–80 loss.

Glenn Seaborg and President Gerald Ford.

Jimmy Carter’s early career as a nuclear engineer in the Navy brought him in contact with Seaborg, and the two kept in touch when the former became president in 1977. Seaborg advised Carter on the development of nuclear power and arms control, but soon found that Carter was not an advocate for civilian nuclear power, which limited Seaborg’s influence within his administration.

As with many of the others, Seaborg knew Ronald Reagan prior to his being elected to the White House. During Reagan’s administration, Seaborg participated in the National Commission on Excellence in Education. In a 1983 report titled “A Nation at Risk,” Seaborg notably contributed the passage, “If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might have viewed it as an act of war.”

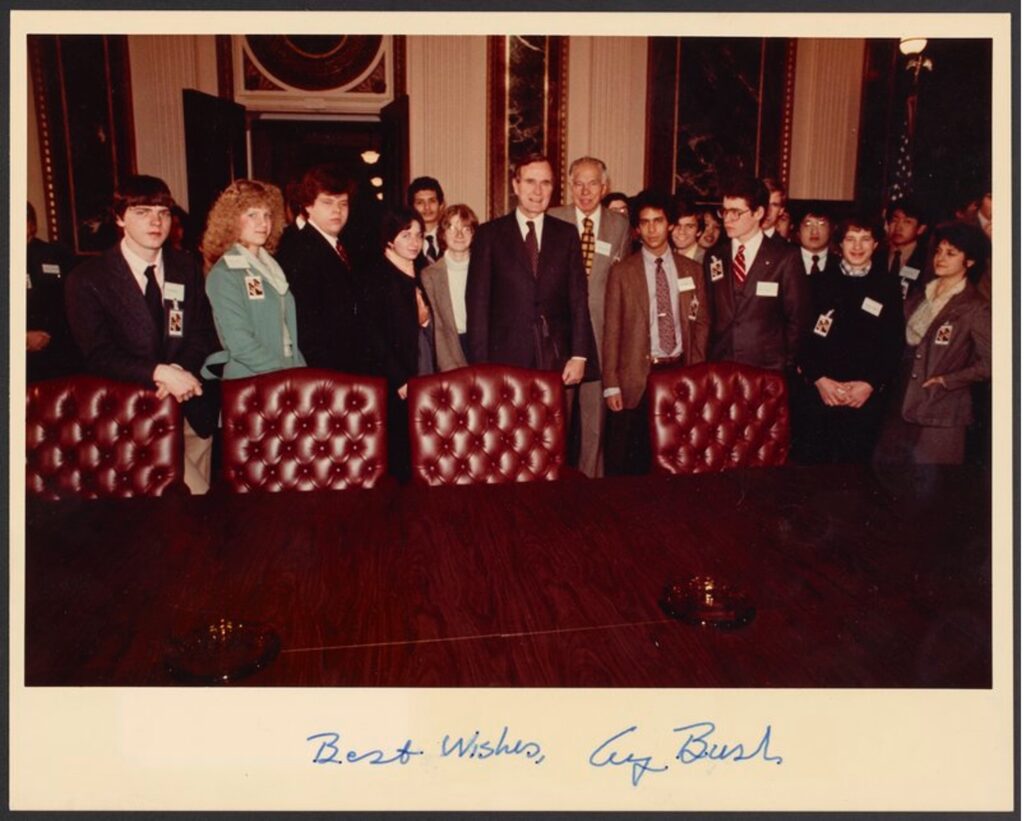

In 1989 President George Bush called Seaborg when he needed a scientific briefing on some astounding news. Researchers at the University of Utah announced they had developed cold fusion, and with it, a cheap, unlimited source of clean energy. Economic prosperity and an end to world tensions over oil supplies was presumably in reach. Unfortunately for the president, Seaborg was quick to temper Bush’s expectations. Seaborg expressed doubt that the phenomena was real, noting, “scientists are as skeptical as economists of getting something for nothing.” Controversy in the chemistry world ensued, but Seaborg, of course, proved correct.

Glenn Seaborg with George Bush and an unidentified group.

As Seaborg’s influence on national policies waned, he spent more and more time as a researcher and educator. Indeed, his visits to the Clinton White House were almost entirely related to issues of science education. Seaborg fondly recalled his days working with various administrations in the White House. Reflecting on his service to multiple presidents, he stated, “I consider myself privileged to have had the opportunity to become acquainted with these men, who have so much shaped history—most of whom I am pleased to say I also like as individuals.” His service to science and the nation ended with his death in 1999.

If you are interested in Seaborg’s story, you can make an appointment to use the Records of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory – Nuclear Division or check out our digitized material on Seaborg.

Featured image: Glenn Seaborg shaking hands with Lyndon B. Johnson, from the Records of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory – Nuclear Division. Science History Institute.

More and more digital research tools are helping to answer even the smallest collections questions.

In pursuit of something memorable and meaningless.

How does a museum and library negotiate biography, civics, and the history of science?

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.