‘High’ School Science

Most object labels tell us what something is. Why one in our collections tells us what something is not.

Most object labels tell us what something is. Why one in our collections tells us what something is not.

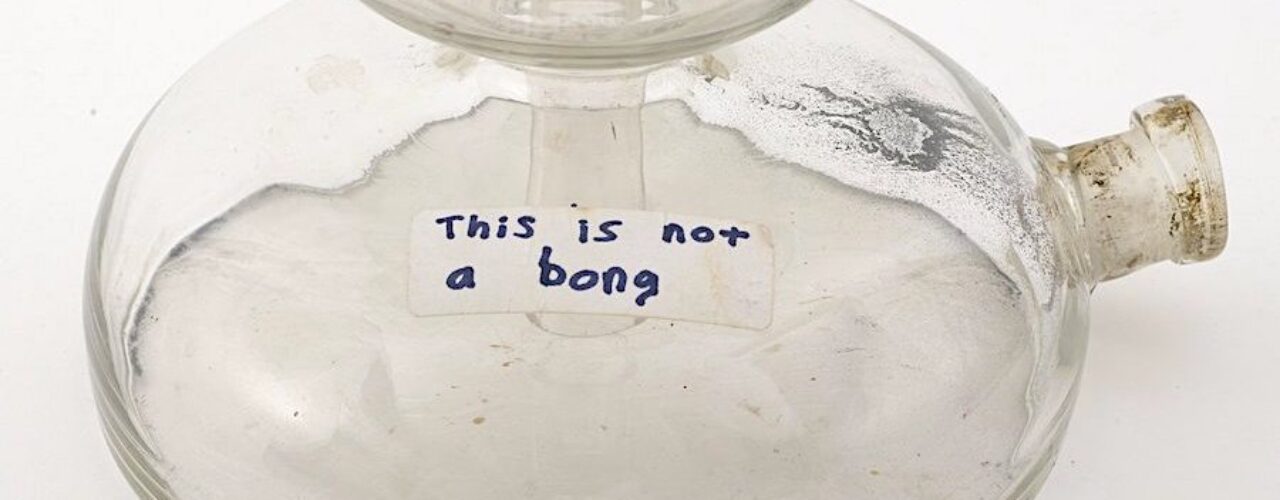

If you explore our digital collections, you might come across an oddly shaped piece of glassware that was once a familiar object in chemistry laboratories. It’s called a Kipp’s apparatus and the Science History Institute has several of these instruments, including one on display in our museum in Philadelphia.But another Kipp’s apparatus in our collections has a better provenance—and a surprising label.The Kipp’s apparatus, also known as the Kipp generator, was invented by Petrus Jacobus Kipp in 1844. The tool was widely used in labs and educational demonstrations into the second half of the 20th century. In a family publication, you might say it looks a bit like a snowman. In less formal company, you’d agree that it would look more at home with 1960s hippies than 19th-century chemists.

Full view of the Kipp’s apparatus.

This Kipp’s apparatus was donated to the Institute by Jeremy Wolf, a chemistry teacher at Palisades High School in Kintnersville, Pennsylvania. A decade after he donated it, Wolf told an Institute curator the story behind the label.

Wolf received the apparatus from his grandmother, Margaret Murray, who had worked as a teacher in Wyomissing, Pennsylvania. She had received it from a student’s parent, who Wolf believes purchased it from a medical supply company in Reading, Pennsylvania. (The glass apparatus was produced by Reading Scientific sometime in the late 1800s or early 1900s.) Murray asked her grandson if he’d like it for his classroom. She thought it might inspire the kids.

Wolf displayed the apparatus in a glass cabinet in the “independent science research team” room at Palisades High School. When kids asked about it, Wolf explained it was an historical piece of chemical equipment. It could be used for capturing hydrogen generated by reacting acids and metals.

One day the school principal walked in, perhaps to do a teaching evaluation. The principal noticed the Kipp’s apparatus. “It kind of looks like something illicit,” he told Wolf.

“Don’t worry,” Wolf replied. “It’s not a bong.”

Then a student sensibly suggested it needed a label. Wolf agreed. To his surprise, the students decided the appropriate label was not “Kipp’s apparatus” but “This is not a bong.”

Later, the principal decided that perhaps it should not be displayed.

Beyond inspiring student creativity, this Kipp’s apparatus once served as a set decoration for the school’s fall play. Wolf also tried to use it to capture hydrogen with his Advanced Placement chemistry students after the AP exam. But missing some connectors, this apparatus was leaky. It also requires a lot of strong acid to work effectively, so it was not a good fit for a high school science lab.

Finally, in the summer of 2012, Wolf decided to donate it to what was then named the Chemical Heritage Foundation (now the Science History Institute). As he rode the subway to the Foundation’s museum and library, the Kipp’s apparatus peeked out of a cardboard box. A fellow rider noticed it and complimented Wolf: “That’s a pretty cool bong!”

More and more digital research tools are helping to answer even the smallest collections questions.

In pursuit of something memorable and meaningless.

How does a museum and library negotiate biography, civics, and the history of science?

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.