History Is a Piece of Cake

What are cookbooks doing in a history of science collection?

What are cookbooks doing in a history of science collection?

You’ve probably heard that cooking is an art, but baking is a science. This adage stems from the fact that baking relies on precise measurements and chemical reactions, and applies principles of physics and biology to create delicious treats. That’s the essence of food science. However, both baking and cooking reflect science, technology, and the culture of the times.

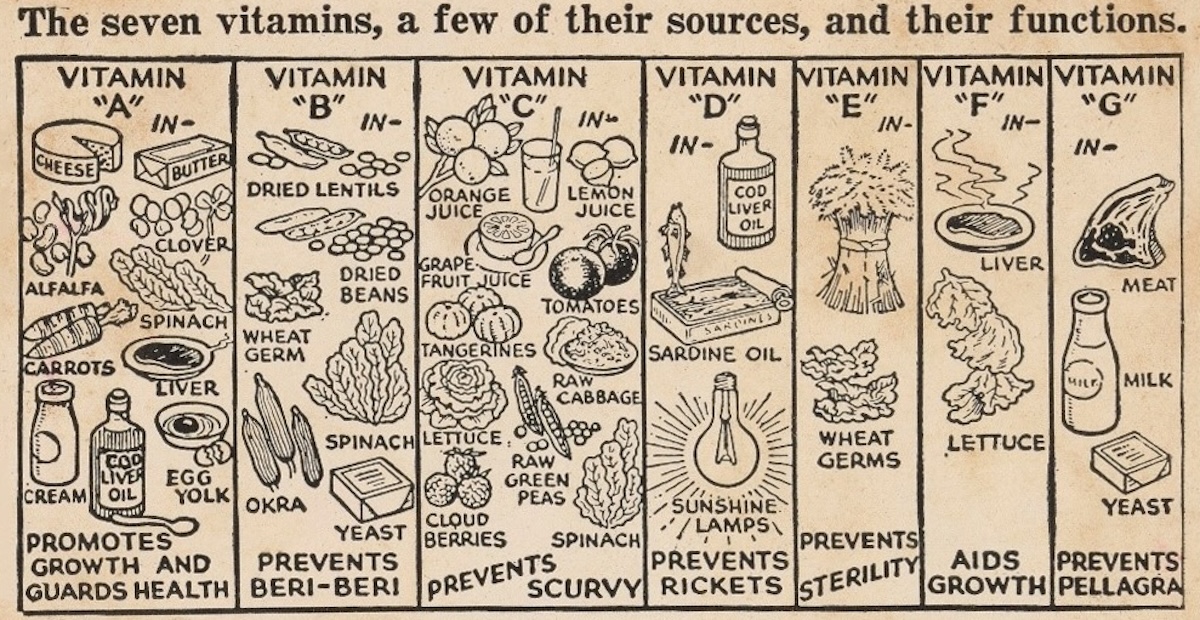

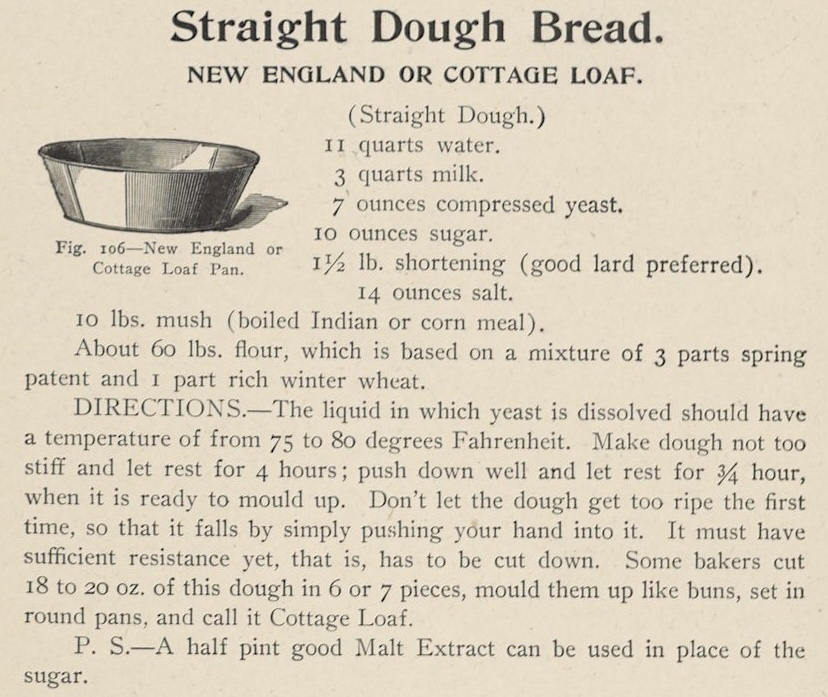

This scientific and historical approach to cooking and baking explains why there are cookbooks in the Science History Institute’s collections. Some were acquired via associations or organizations, such as the Society of Flavor Chemists. Others were donated by people who used them for study. We also acquire recipe- and cookbooks for exhibitions, or collect them as primary resources in science history. From industrial bread production manuals, to the chemistry behind perfect Jell-O, these works reveal how scientific principles moved from laboratories into home kitchens.

While it would take longer than a blog post to fully detail everything about food science in our collections, I wanted to give a quick overview of the extensive number of resources we hold and then highlight some of our more surprising items.

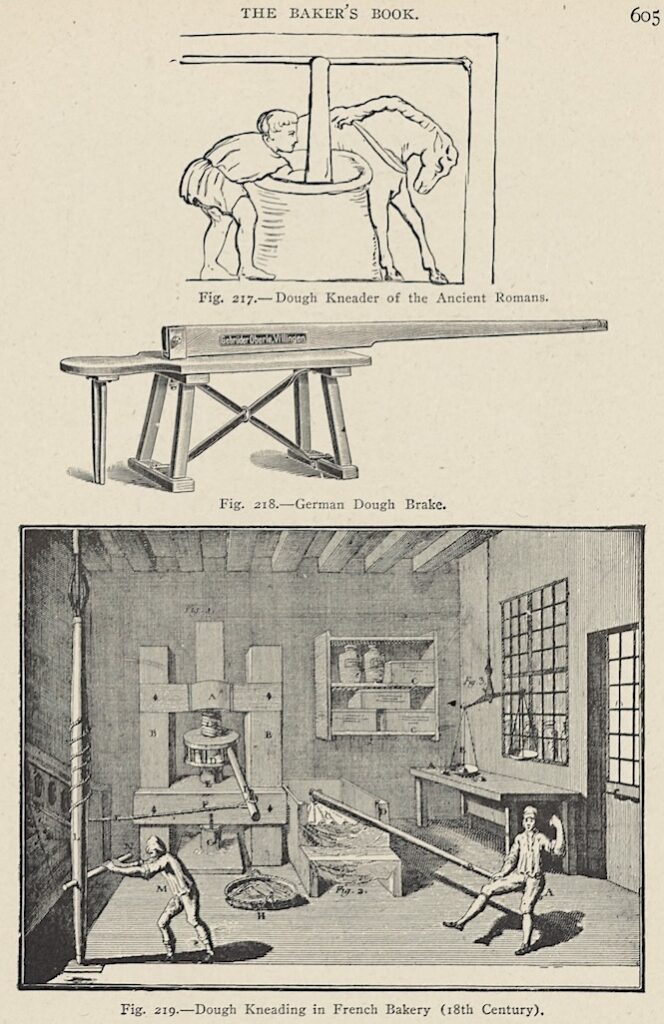

Left: Published by the Kellogg Company, The Housewife’s Almanac: A Book for Homemakers (1938) includes recipes that utilize Kellogg’s All-Bran product; Right: illustrations of dough kneading technology across the ages, from The Baker’s Book, Volume II (1903).

Our food science collection might surprise you: it’s filled with European breadmaking manuals, industry journals like The Cheese Press, home and promotional cookbooks, and almanacs that offer a fascinating window into chemistry, food preservation, the evolution of kitchen technology, and nutrition. These resources, which include this charming image from Clabber Girl: The Healthy Baking Powder (1931), give us a unique lens into how science has shaped what and how we eat.

Domestic technology is where food science has become part of everyday life. Cookbooks can reflect aspects of day-to-day life that can get lost in history. But beyond nailing down your grandma’s recipe, cookbooks also reflect the technology and culture of the time. Many cookbooks had menu suggestions, etiquette advice, and food guides.

For instance, the Kellogg Company’s The Housewife’s Almanac dedicates many pages to fun facts, astrology, and wedding etiquette in addition to recipes.

Pages 12 (left) and 16 (right) from The Housewife’s Almanac: A Book for Homemakers, 1938.

From the late 19th to the mid-20th century, promotional cookbooks were a popular way to introduce audiences to the benefits and uses of new products.

These promotional cookbooks had to convince readers their product was the best, whether it was Rumford’s “no-powder taste” baking powder or Kellogg’s cereal, with its promise of better digestion. In short, companies essentially told consumers to trust the science behind the brand.

Clearly, these books were made for more than just baking a pretty cake. With such a fascinating collection at my fingertips, I had to put one of these older recipes to the test.

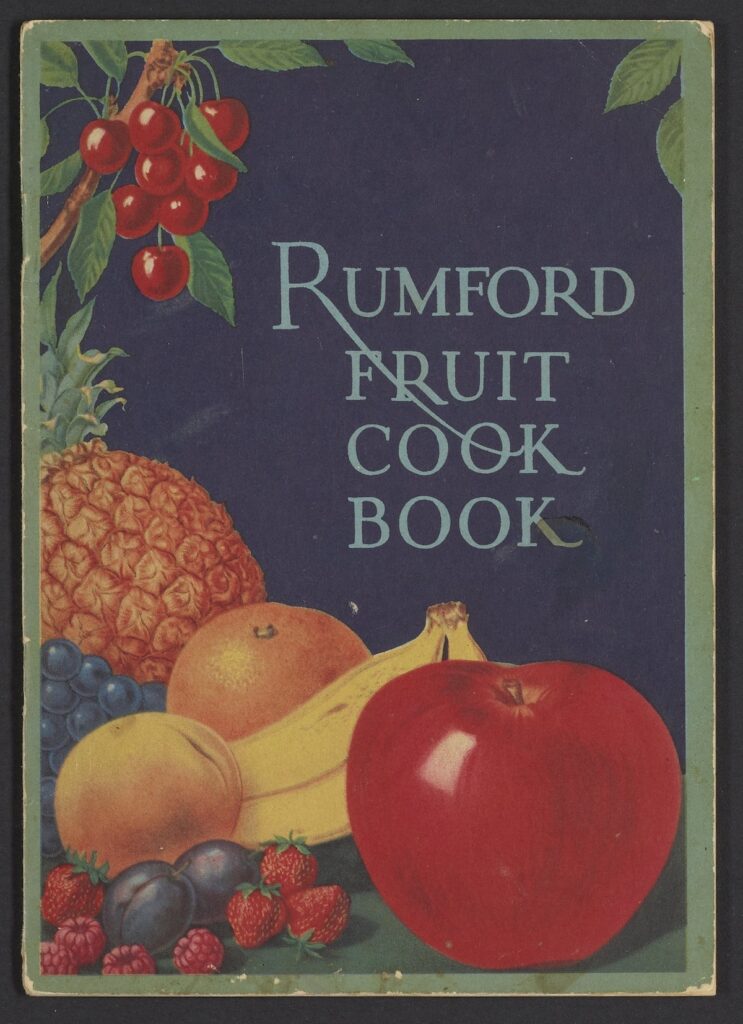

I decided to cook a recipe from Rumford Fruit Recipes (cover title: Rumford Fruit Cook Book), written by Lily Haxworth Wallace in 1927. This book is gorgeous—plus I love baking with fruit and wanted to use what is in season. Since Rumford baking powder is still sold today, I could make the recipe exactly as intended.

The cherry on top (pun intended!) was that the book was written by a woman. I always want to highlight women in science and explain what types of science women were “allowed” to study and practice.

Wallace, who trained at the National Training School of Cookery in London, wrote cookbooks from 1908 through 1950. Many of her books (like this one) were written in partnership with Rumford Baking Powder. The Science History Institute also holds both 1945 and 1948 editions of the Haxworth-authored Rumford Complete Cook Book.

As I mentioned, cookbooks are a great snapshot of a time in history that can help us understand what was happening culturally and technologically.

For example, this cookbook was published in 1927 during an economically stable time, right before the Great Depression. Refrigeration and processed foods were becoming more common, and canning technology had significantly improved. Rumford Fruit Recipes even notes that, unlike today, fruit wasn’t readily available year-round. Reading about this different food landscape made me even more excited to try my hand at a recipe from this cookbook.

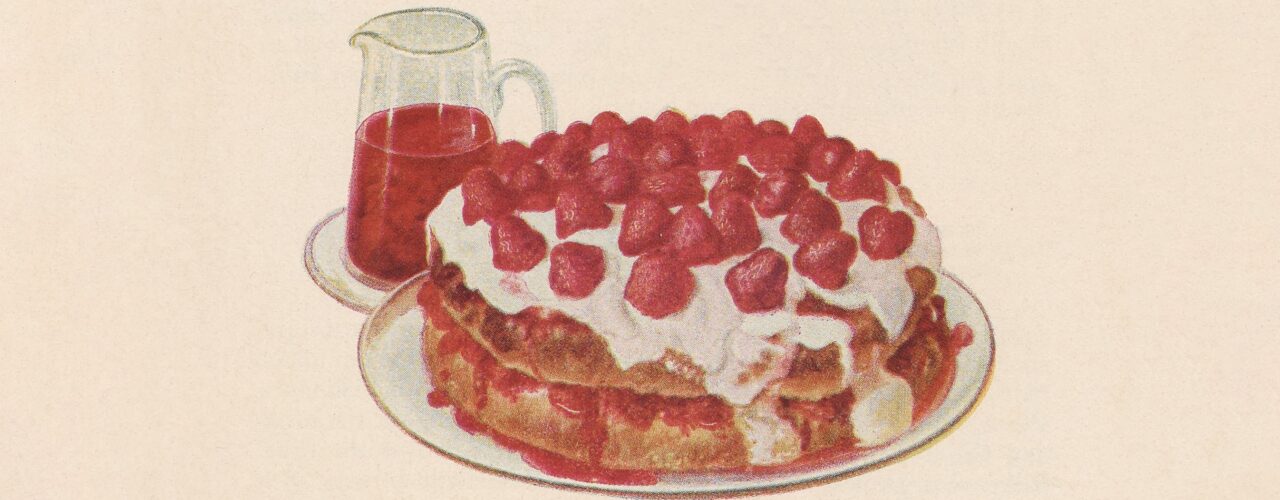

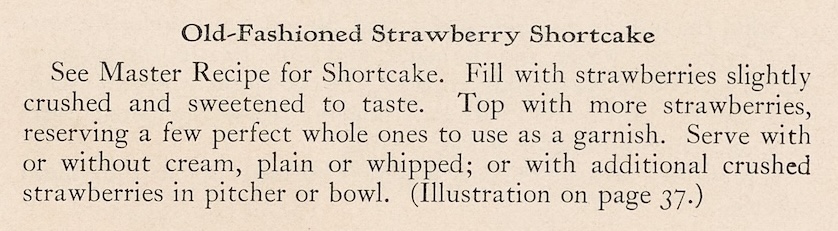

I decided to bake the “old fashioned strawberry shortcake” from page 12—partly because it’s strawberry season and partly because of the fantastic illustration of the cake on page 37.

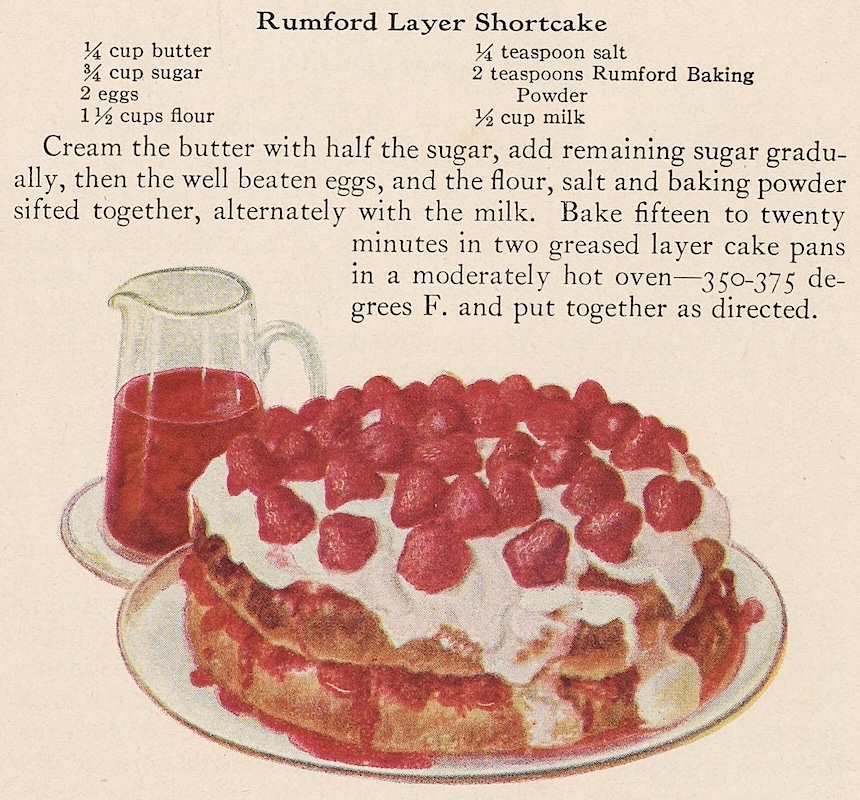

My baking objective, described on page 12 (top) and pictured on page 37 (bottom) of Rumford Fruit Recipes.

The cake has three components: the cake base, fruit filling, and whipped cream topping. Let me walk you through each one.

The strawberry shortcake recipe instructs us to use the master recipe for a “Rumford Layer Shortcake” on page 37 (pictured above) for the cake element.

Cream the butter with half the sugar, add remaining sugar gradually, then the well-beaten eggs, and the flour, salt, and baking powder sifted together, alternately with the milk.

Bake 15 to 20 minutes in two greased layer cake pans in a moderately hot oven, 350–375°F, and put together as directed.

The strawberry shortcake recipe tells us to “fill with strawberries slightly crushed and sweetened to taste.” I opted to combine strawberries with rhubarb for my filling. Below is my personal filling recipe, taken from different parts of the Rumford Fruit Cookbook, as well as my own intuition (so maybe baking is an art and a science!)

Following the “Rhubarb Slump” recipe on page 36, I cooked the rhubarb, sugar, and water together until the rhubarb was broken. Then I prepared the strawberries, “lightly crushed and sweetened to taste,” and mixed the cooked rhubarb and fresh strawberries.

To top everything off, the strawberry shortcake recipe suggests serving the cake “with or without cream, plain or whipped.” Sadly, there were no explicit instructions for whipped cream. I decided that I would do what I assumed most home cooks would do: make their own to their own taste.

I measured some heavy whipping cream into a bowl and added about ⅛ of a cup of powdered sugar and a splash of vanilla extract.

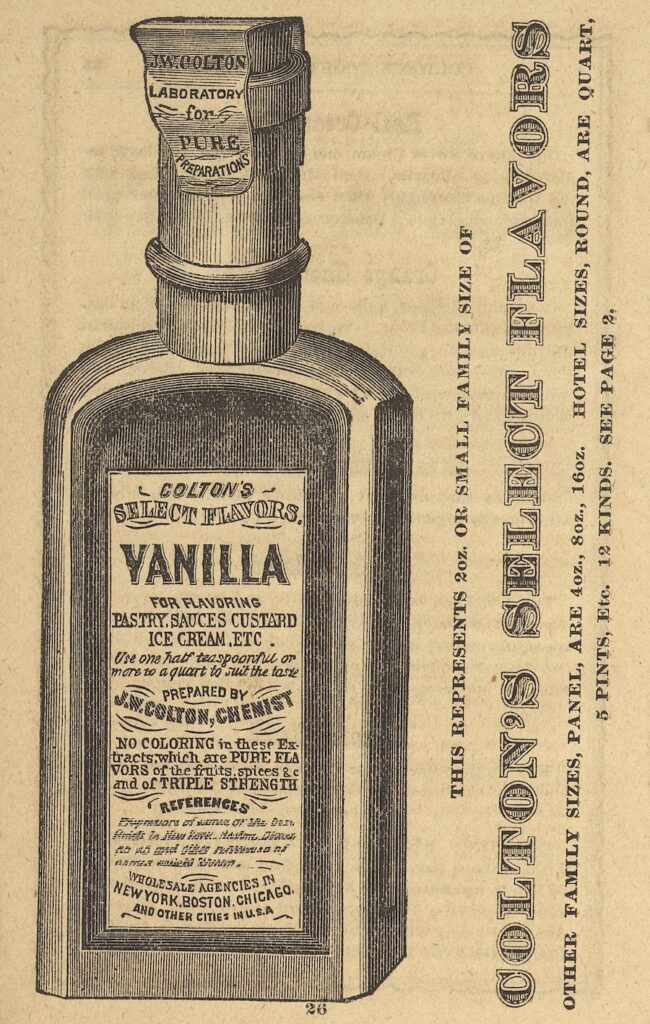

To my surprise, vanilla extract has been used in baking since the mid-1800s, so I was successful in preserving the historical accuracy of the recipe! I used a hand mixer to whip the cream into stiff peaks.

I was amazed that this 98-year-old recipe felt so current. I had expected baking times and temperatures to be vague and measurements to reference unfamiliar sizes. For example, J.W. Colton’s Choice Cooking Recipes, Preparations and Calendar for 1876-77 instructs us to use a “wine-glass of yeast” (which, thanks to Google, I know is a quarter of a cup). Other recipes have measurements such as “enough milk to make a thick batter.”

Here’s a side-by-side comparison of the Rumford shortcake and my cake.

The Rumford shortcake recipe was easy to understand and the measurements were standardized. Page 47 of the book even has a table of baking times and measurement guides. This recipe is now one of my favorites and will become a regular rotation in my house! I loved the simplicity and freshness of the cake.

Want to try your own historical cooking experiment? Our collections are full of these old recipes waiting to be rediscovered! Here are some of the more interesting ones I found:

Featured image: Old-Fashioned Strawberry Shortcake, illustration from Rumford Fruit Recipes, 1927.

Memory, materials, and the history of science in the Eugene Garfield Papers.

Explore the history of science behind U.S. efforts to feed schoolchildren with Lunchtime exhibition curator Jesse Smith.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.