The Power of Perspective

How contrasting stories found in our collections help us embrace the complexity of the history of science.

How contrasting stories found in our collections help us embrace the complexity of the history of science.

As a fellow in the Science History Institute’s new curatorial fellowship program, which is aimed at diversifying the career opportunities of scholars, I’m developing methods to use the Institute’s oral histories in our museum. The Center for Oral History conducts and collects interviews with scientists, who share their experiences and perspectives in their own words. I’m investigating how stories from these interviews can help further the museum’s mission of making science accessible to everyone. To do so, I’ve surveyed how other museums use oral histories in their exhibitions and I am exploring how the Institute can learn from these institutions. Through this experience, I’ve rediscovered the power of oral histories and artifacts when they are brought into conversation with each other.

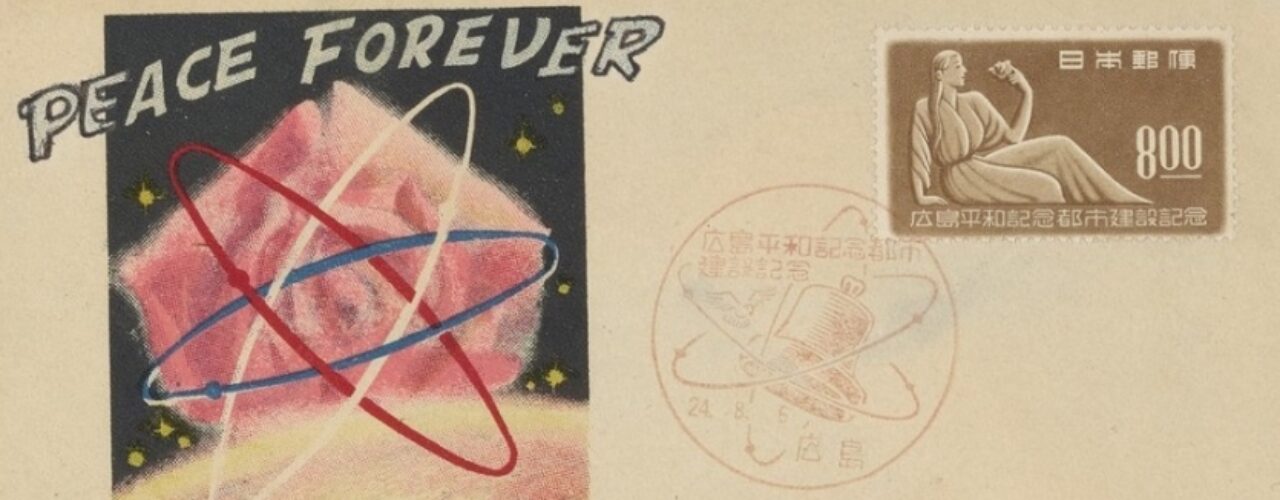

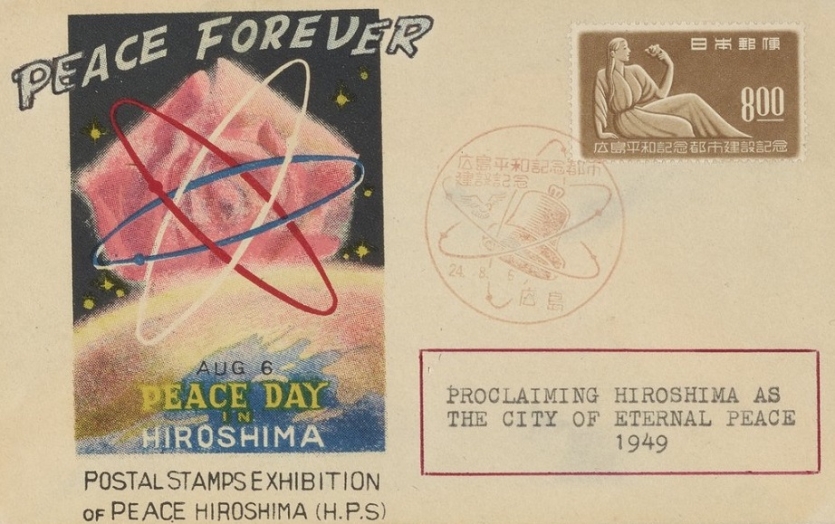

I grew up in Hiroshima, Japan, where the legacy of the atomic bomb gave particular weight to the ways objects and first-person narratives interweave. As a school child, my first encounter with American science was via the testimony of the Hibakusha (A-bomb survivors). During a special program broadcast on Hiroshima’s Atomic Bomb Memorial Day on August 6, I listened to an oral history that told of a Japanese doctor who discovered that the bomb’s radiation had exposed his X-ray films. Later, while working at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, I imagined the stories behind artifacts in the museum’s collection—a burnt tricycle, a charred bento box, and a pocket watch stopped at 8:15 a.m.

If we don’t know the stories behind these objects, they are simply remnants of mundane, everyday life. History can explain some facts behind these objects: we learn that the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and that the bomb’s detonation explains why these X-ray films are exposed, why the contents of the bento box remain uneaten, or why this watch stopped at 8:15 a.m.

However, without the perspective of first-person accounts, history cannot explain that grieving parents buried the tricycle as a surrogate for their lost child and, decades later, recovered the rusted piece to donate to the Peace Memorial Museum. This story not only adds depth to our understanding of a historical object, it also adds nuance and perspective to our understanding of history—in this case, America’s development of nuclear technologies.

As a curatorial fellow, I bring my awareness of the complex history of American science to the Institute’s scientific artifacts. For instance, during my colleague Roger Turner’s “From NMR to MRI” talk, I learned that our NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) spectrometer, a Varian A-60 Proton NMR console, earned the terrifying nickname “Crisis Detector” because its users had such a hard time handling this delicate and unreliable early model.

During Roger’s talk, I was fascinated by the human story behind the instrument and became curious about how I could combine our oral history collection and the NMR machine. I discovered the story of biochemist Mildred Cohn, who used NMR to investigate the role of enzymes in the body in order to understand how metabolism works. In her oral history interview, Cohn also remembers that it “took months to get [the early NMR machine] to work, because Varian did not have a temperature control on it. They were used to Palo Alto where the temperature is fairly constant. In St. Louis the temperature could drop 40 degrees in a day.”

Considering how delicate the original NMR machine was, I didn’t think this technology would be widely adopted. On the contrary, the talk explained, today medical practitioners use NMR technology as MRI (magnetic resonance imaging)—a multidimensional NMR imaging method—to diagnose illnesses and injuries. Nuclear magnetic resonance helps countless people become healthy and live longer.

However, the word “nuclear” in “nuclear magnetic resonance” elicits complex feelings for me, a historian who grew up in Hiroshima. In the NMR console, I see not only a story of beneficient science, but also the stories of nuclear bomb victims and survivors, and a larger story of science’s role in warfare.

While the stories behind our NMR machine reveal a great deal about the history of American science, stories and artifacts from Hiroshima offer a completely different narrative about American science told from a non-American, non-scientist perspective.

The stories from Hiroshima and the U.S. are not contradictory, and both are important for understanding a fuller account of American science. In fact, when such stories intertwine, they help us embrace a more complex—and oftentimes emotionally difficult—set of histories. In this case, we learn the history of American science in two different times and contexts, working toward quite different aims: one, the taking of lives; the second, the saving of lives.

These objects and stories helped me weave this corresponding pair of histories with radically different outcomes. Even as a historian, I am still struck by the power of objects and stories, a power that enables us to embrace the complexity of science and its history.

In pursuit of something memorable and meaningless.

How does a museum and library negotiate biography, civics, and the history of science?

Searching for the cats hiding in our collections.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.