Weaving History

What do Qing dynasty paintings reveal about the secret of degumming ramie?

What do Qing dynasty paintings reveal about the secret of degumming ramie?

Ramie, one of the oldest fiber crops used in textile production to be mentioned in Classic of Poetry (ShiJing, 诗经), is exported from China to Europe under the name China-grass. Ramie cloth is as smooth as silk and as breathable as cotton, and is therefore excellent for summer and celebrated as the “summer cloth” (XiaBu, 夏布). Despite its alluring qualities and the reference to China in its English nickname, ramie sounds esoteric to contemporary ears and the technology of producing summer cloth is not well understood. However, the Science History Institute has in its collections The Story of Ramie from Seed to Finished Garment (ca. 1820–1870), five albums of watercolor paintings from Qing China that visually document the entire process of ramie production, from planting to making clothes.

The albums were produced by Sunqua (新呱) (active 1830–1870), a Cantonese artist who drew export paintings for foreigners. Though Sunqua probably emphasized the aesthetic value of the albums as souvenirs, as a graduate student studying the history of science, I am interested in reading the albums as a scientific text and interpreting the technical details of making ramie clothes.

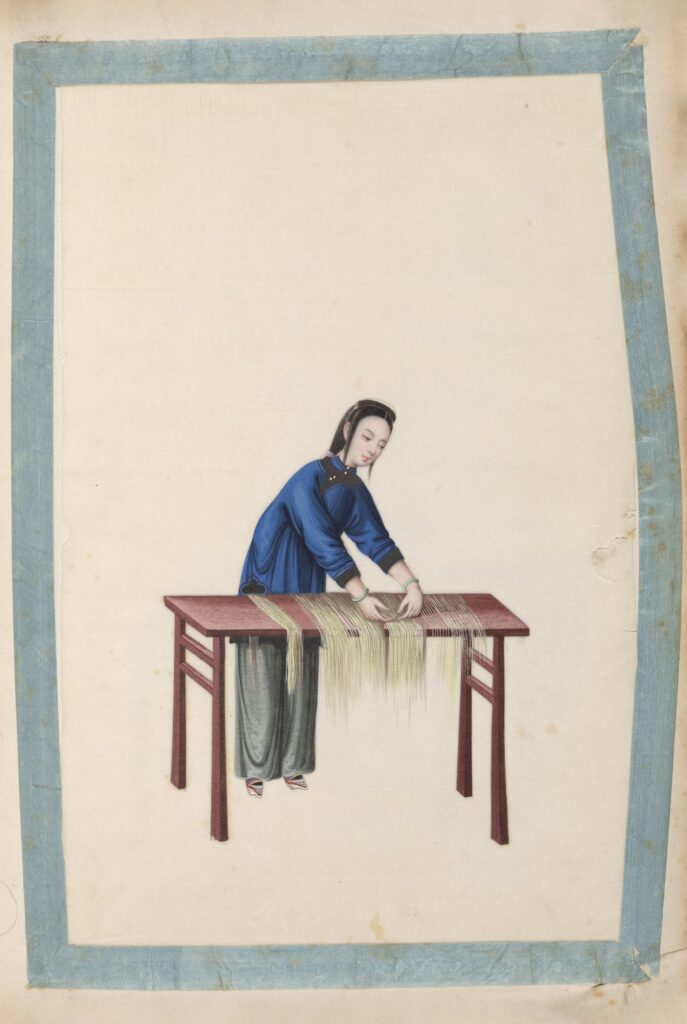

While summer cloth is not woven or tailored differently than cloth made from other fibers, making yarn from the ramie plant is a special, four-step process: harvesting the plant; scraping, which removes the fiber layer from the cortex and inner wooden body; separating the fibers by hand; and finally, twisting, splicing (connecting two fibers to make a continuous long one), and spinning the fiber into yarn, as showcased in the albums.

Though this seems straightforward, the ramie plant contains a specific kind of gum that needs to be removed to make the yarn soft and white, and degumming technology varied across regions and periods. How did the average person with a limited understanding of chemicals bleach and soften ramie in 19th-century China? In other words, what secrets of degumming do the albums reveal? To interpret the paintings, I turned to three ancient Chinese texts that offer clues about premodern textile technology.

Written nearly 600 years before the ramie albums were produced, Compilation on Agriculture and Sericulture (NongSangJiYao, 农桑辑要), a text composed by Yuan officials in 1273, suggests soaking and boiling ramie yarn in order to degum it:

Another Yuan text, Wang Zhen’s Book on Agriculture (WangZhenNongShu, 王桢农书) (1313) introduces a different degumming method—steaming the ramie plant itself before the yarn is produced:

Finally, like Compilation on Agriculture and Sericulture, the Ming text Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century (TianGongKaiWu, 天工开物) (1637) suggests degumming by boiling the fibers before they are spun into yarn:

Though they don’t use the word “degum,” these texts suggest that ramie gum is removed, as they emphasize that ramie becomes soft and white. According to the texts, degumming can take place on the plant, fibers, or yarn, and usually requires water, heat, and the use of certain ashes.

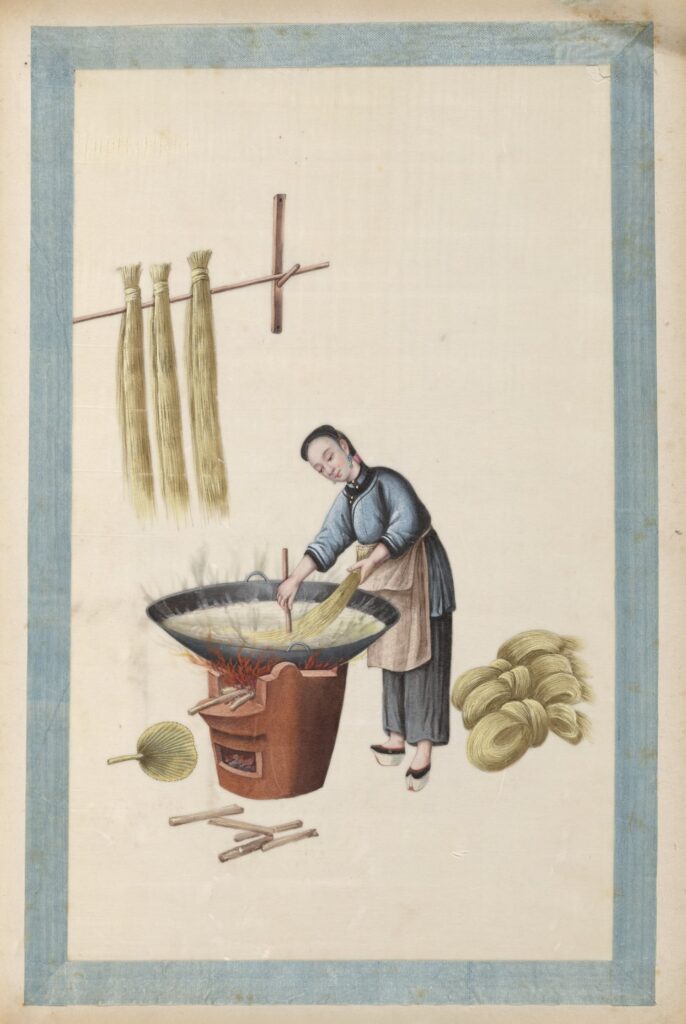

So what are the degumming techniques illustrated in the ramie albums at the Science History Institute? These paintings were produced in the Qing dynasty, hundreds of years later than these three texts. I believe that two of the album’s paintings illustrate the degumming process. In the image above, ramie fibers are boiled after being twisted into coarse threads.

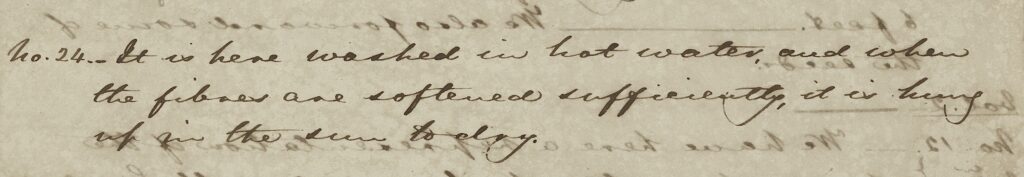

Here a woman boils the coarse threads in a cauldron. Raw threads lie at her feet and boiled ones hang to dry. According to a handwritten transcript that accompanies the album, “It is here washed in hot water, and when the fibres are softened sufficiently, it is hung up in the sun to dry.”

This preliminary “washing” of ramie fibers echoes the boiling method described in Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century. The coarse threads are washed in hot water without being mixed with ashes, which makes this process also like the steaming method recorded in Wang Zhen’s Book on Agriculture.

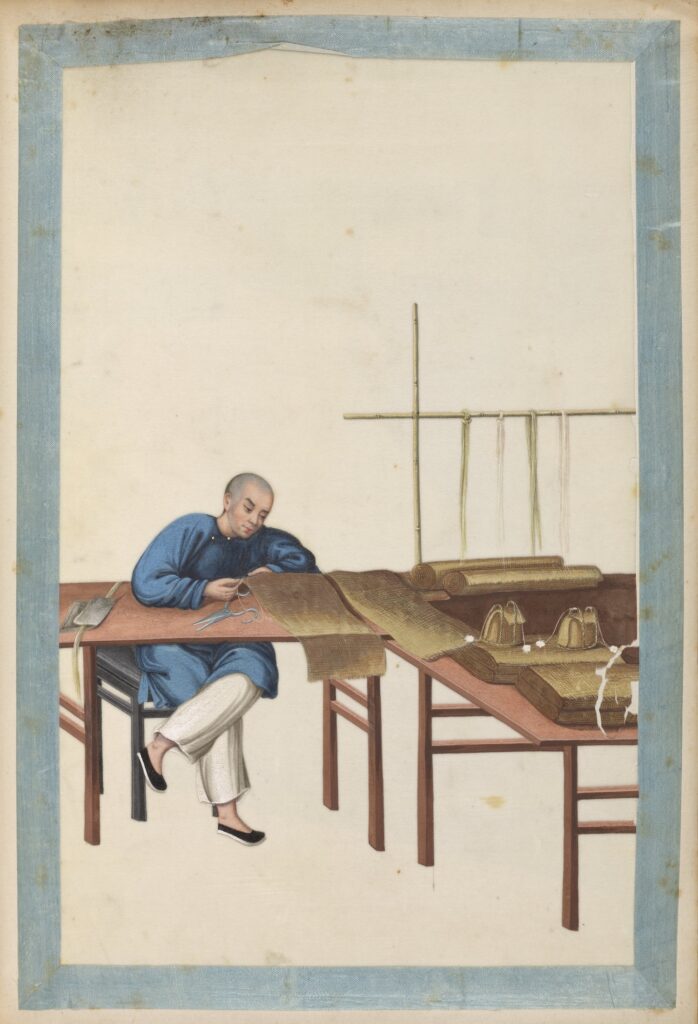

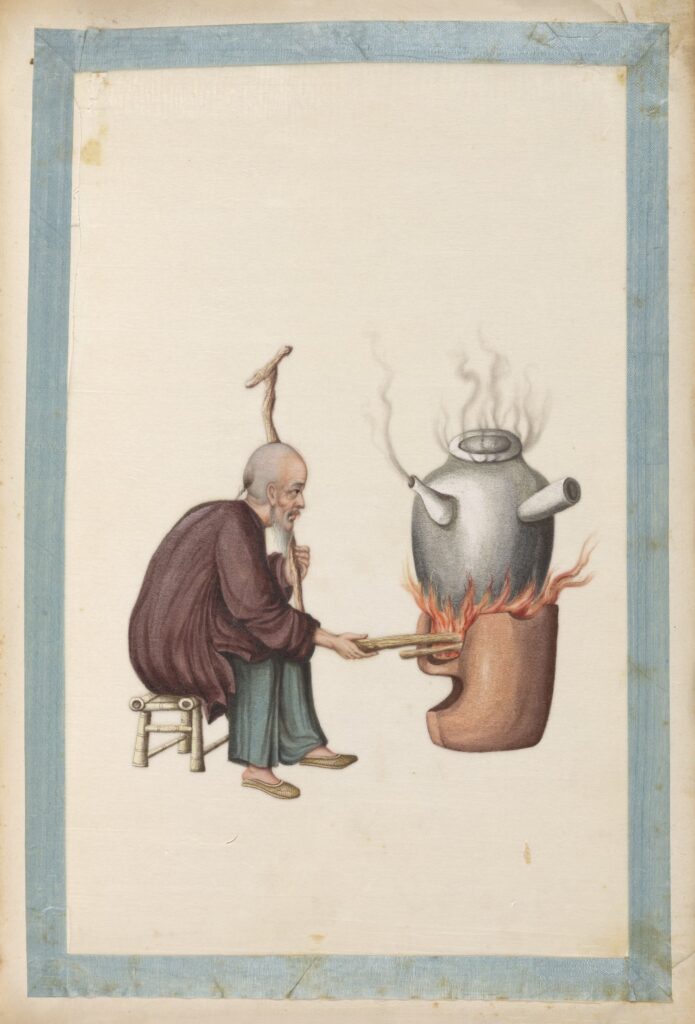

According to the albums, the boiled threads are further spliced and spun into fine yarn. Before being woven on a loom, the yarn itself is stewed:

In this painting, an elderly man stews the yarn in a huge metal pot covered with a lid. The accompanying transcript explains: “When the yarn is to be bleached before weaving, it is taken off the roller…and put into hot water, over a hot fire, where it is boiled. With the hot water is mixed the impure carbonate of Potash in the proportions of 2 mace (钱, about 3.73g) to one catty (斤, about 597g) of water.”

The use of “potash” resonates with the first text, Compilation on Agriculture and Sericulture, in which yarn is soaked with mulberry wood ashes and boiled with millet-stalk ashes, as well as the third text, Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century, which says to boil ramie fibers with rice-stalk ashes and lime.

When the Qing albums are read in conjunction with ancient texts, we observe the continuity and discontinuity of textile technology across the centuries. Moreover, while the ancient texts shed light on technical details, the paintings flesh out accounts of ramie production by showcasing the laborers, particularly women, who played a key role in transforming the ramie plant into yarn. We gain a fuller understanding of the historical process of ramie production by considering the ramie album images alongside ancient texts.

[1] This calculation is taken from Dieter Kuhn’s Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology; Part 9, Textile Technology: Spinning and Reeling (1988).

All images: The Story of Ramie from Seed to Finished Garment, Books 1–5, five brocade-bound sets of Chinese watercolor paintings depicting the process of producing ramie, ca. 1820–1870.

More and more digital research tools are helping to answer even the smallest collections questions.

In pursuit of something memorable and meaningless.

How does a museum and library negotiate biography, civics, and the history of science?

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.