Collecting Lives and Live Collections

How does a museum and library negotiate biography, civics, and the history of science?

How does a museum and library negotiate biography, civics, and the history of science?

This blog took flight just about three years ago. Drawing together the esoteric and the everyday, since then it has featured stories on everything from pizza, Radiation Measurement Kits, and cockroaches, to U-matic video cassette tapes, flap books, numismatics, Ping-Pong, and marginalia. Institute staff and scholars have uncovered these and other gems in our library, archival, museum, and oral history collections. But why stop there?

In the last couple of years, I have been collecting stories for the Scientific Biographies, an online educational resource that lives on the Institute’s website. These biographies offer perspectives on the lives of individuals who have contributed to the development and use of scientific knowledge (though many of them lived before the word “science” was used as it is today). Does it make sense to think about these biographies as a collection? What do we mean by “collection,” anyway? And what is at stake?

Librarians often differentiate between “Collections” and “Institutional Repositories.” The latter are thought to preserve the intellectual output of an institution. It might make sense to locate the biographies here, as each one offers a distinct interpretation. Collections proper, on the other hand, provide the fodder for such output—the foundation of what historian of science Lorraine Daston calls “cumulative, collective knowledge.”

With a primary focus on archives, Daston warns against too much hair-splitting when it comes to pinning down the essences of these things. Given their “historical heterogeneity,” she writes, “. . . [I]t makes little sense to seek a definition bound by form, location, content, or proprietor. The boundaries…[have] been historically fluid.”

Generalizing across these differences, Daston argues that scientific archives have certain functions, or behaviors, in common: whether one is talking about the Svalbard Global Seed Vault (which collects germplasms) or the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary Project (which collects words), these collections tend to be “opportunistic and open-ended.” They gather what is available and preserve it for as-yet undetermined ends. And this is precisely why researchers and storytellers find them useful.

Our biographies of scientists who lived and worked in the past are likewise opportunistic. And in digital spaces, they are increasingly open-ended. Because collections are resource-intensive holdings that require active support to maintain, grow, and make accessible, they have tended to favor those with wealth and power. A biographical framing is often implicit in the way materials are accessioned, organized, and preserved. This often means that biases and blind spots are built into collections and into the histories built on them, a quality that has been addressed by scholars and collections managers focused on colonial archives, archival silences, and harmful content. It is one of the reasons why biography often feels conservative or old-fashioned, though new relational and educational schemes hold out the promise of greater accuracy and inclusion.

Today, some guides help people build and describe collections in ways that are more representative and respectful. This doesn’t mean excluding material that is potentially troubling or problematic (categories that are themselves, of course, highly subjective and historically contingent), but it does mean flagging and contextualizing this material as much as possible. One university archive, for example, includes the following in its Statements on Inclusivity & Harmful Content:

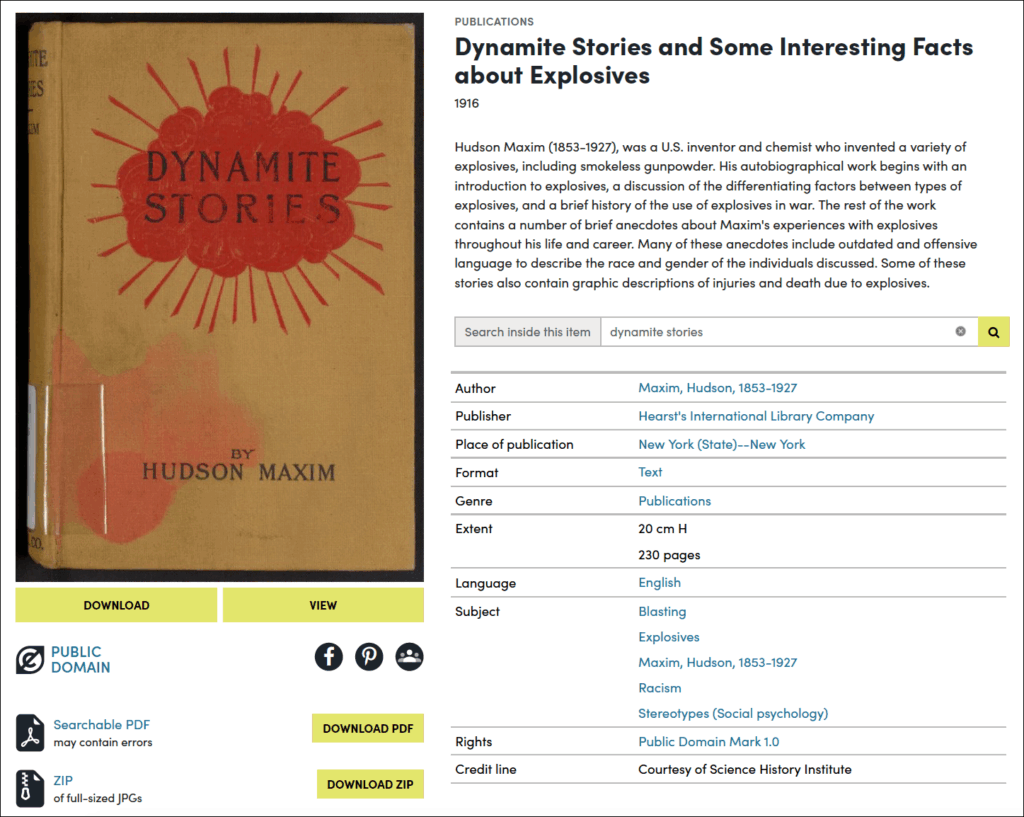

These archivists have, accordingly, committed to flagging “historical materials that contain offensive or harmful languages or images,” but they defend retaining such materials for the sake of “historical integrity.” Similar steps have been taken at the Science History Institute. Here is one example from our digital collections.

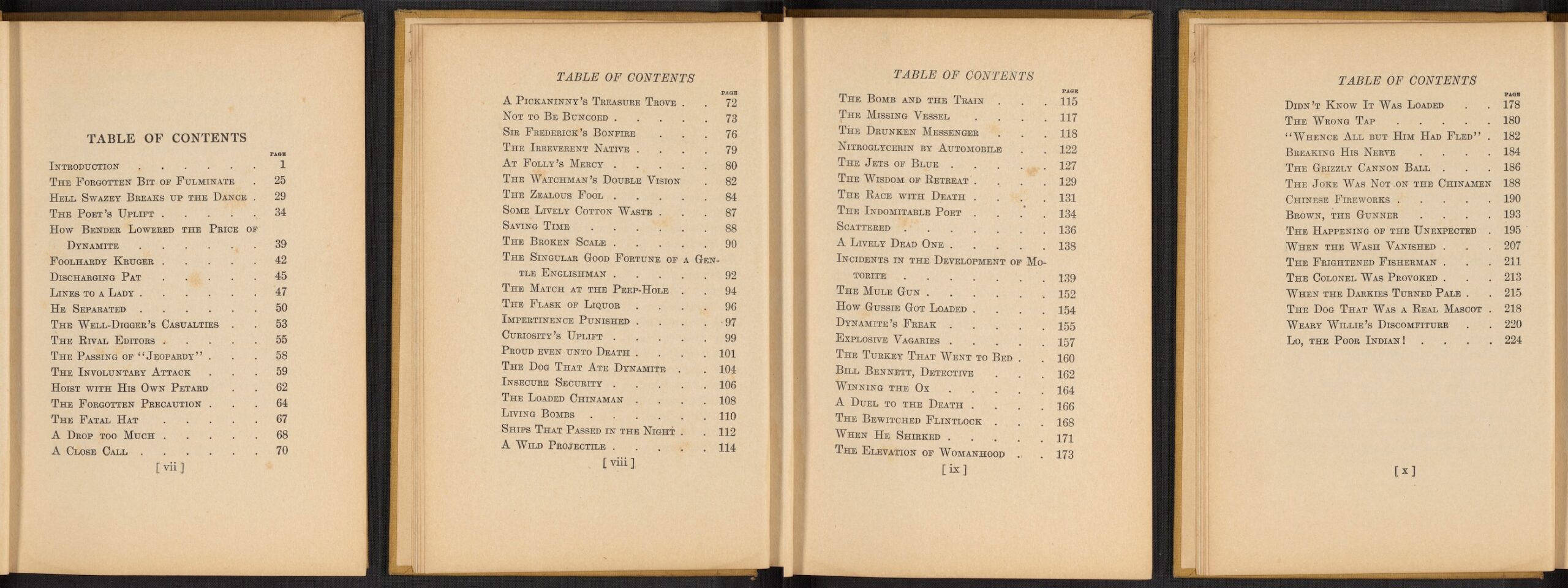

The description of Hudson Maxim’s 1916 book Dynamite Stories indicates that the book includes numerous anecdotes about the author’s experiences with explosives. It notes further, “Many of these anecdotes include outdated and offensive language to describe the race and gender of the individuals discussed. Some of these stories also contain graphic descriptions of injuries and death due to explosives.”

I first encountered this book in the process of editing a new biography of Maxim for the Scientific Biographies. I have read Dynamite Stories and can confirm that it includes offensive language and ideas. At a time when everyone seems to agree that the stakes are high for historical interpretation, I have worried deeply about presenting Maxim’s life and work to our audiences at the expense of telling other stories.

Making Dynamite Stories available to researchers as part of the Institute’s digital collections, for their own interpretation and analysis, is one thing. Library and archival collections have a way of levelling the ethical claims of the materials they preserve. For instance, we hold both the Trinity Photograph Collection, which contains photographs and negatives of the Trinity nuclear detonation, and Photographs from the Papers of Gabor B. Levy, which contain “1950s-era family photographs,” together in a common infrastructure despite obvious differences in content. But should different standards apply to something that is part of an institutional repository, or even an educational resource? Since Plutarch, audiences have been looking to biographies for insights about how to live, which suggests that subject selection cannot be leveled here in the same way.

Maxim’s life story is interesting, to be sure. He grew up in extreme poverty in rural Maine, made a small fortune through the development of smokeless gunpowder, and used that fortune in later life to invest in the conservation of the area around Lake Hopatcong, New Jersey. He lost his left hand in a mercury fulminate explosion, loved poetry almost as much as he loved guns, and he twice presented the Miss America trophy dressed as King Neptune.

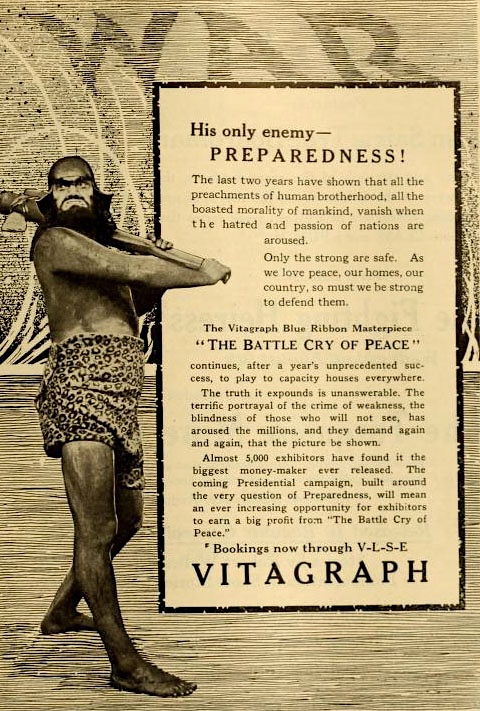

Maxim’s case study can highlight numerous threads and historical lessons. Along with the development of high explosives, he wrote extensively on the theory of military deterrence. As someone who was desperate to learn, but who often had to miss school to work before Maine enacted compulsory education laws in 1875, Maxim’s autobiography opens a window onto the early history of U.S. public education. At the same time, his commitments to the democratizing function of education and his belief in the “bootstrapping” need to pull oneself up fed into a strongly eugenicist and nativist philosophy that are clearly harmful to specific groups and civil society writ large.

Maxim’s story would not be the only one in the Scientific Biographies to contain controversial and potentially harmful content (whether understood exclusively in reference to our own species or extended to other life forms). Does inclusion of such examples on the basis of “historical integrity” make sense for this collection?

I have looked to social studies educators for guidance on this question. Members of the National Council for the Social Studies have developed standards for civics and history, for example, that provide a helpful reference. In defining civics, they write:

I believe there is a need to see scientific research, innovation, and communication as a form of civic participation, in line with this definition. Crucially, “not all participation is beneficial.” After all, scientific ideas—for example, ideas about racial difference and human development—have often been invoked in limiting the participation of certain groups in deliberative processes. That said, at its best, scientific practice does hold up a compelling model of deliberation, “making choices and judgments with information and evidence . . . and concern for fair procedures.” We need to fold the history of science into contemporary civics education not merely because it contains examples of civic virtues and vices, but because it sheds light on the very conditions of civic participation in the first place.

The civics “pathway,” like the other disciplines included in the social studies standards, is elaborated through a series of grade-specific “indicators.” These indicators are concepts students are expected to have mastered by a series of benchmark years in school. Examples from the history pathway support the idea that it is important for students to confront perspectives that they may find objectionable. Here are just a few examples:

I am especially interested in the last two indicators cited above. Perhaps one of the most valuable lessons students can learn here is that history, like science, is always on the move. We should fully expect that “the perspectives of people in the present [will] shape interpretations of the past” and that these will continue to change over time. This is why we are now emphasizing authors’ motivations and perspectives with new additions to the Scientific Biographies, among other developments.

History is less about “getting it right” than it is about entering into an open deliberation with each other and the sources we have about the past. Recognizing, then, that sources like Maxim’s Dynamite Stories were created in distinct contexts for particular audiences and purposes is just plain literacy, which every student needs.

Maxim wanted to promote access to education because he thought it would make for a stronger democracy. He also defended members of the Confederacy and wanted to close U.S. borders. He cared deeply about the nature he found in his backyard and dedicated resources to its protection. Maxim also destroyed people and places through his work with high explosives. His story, like others in the Scientific Biographies, is complicated. This is why it makes for a good educational resource—he breaks down straightforward assumptions students might have about “good guys” and “bad guys” and he forces us to reckon with our own values about what constitutes the “good” and the “bad.”

All of that said, collecting and contextualizing harmful content is just part of what reparative work might look like for an interpretive collection like the Scientific Biographies. The larger task at hand is to collect stories that reflect the wide range of contributions, contributors, values, and priorities that have constituted “science” over time.

Featured image: Detail of the cover of Dynamite Stories by Hudson Maxim, 1916.

Mapping Philadelphia’s industrial past with digital tools.

Memory, materials, and the history of science in the Eugene Garfield Papers.

Explore the history of science behind U.S. efforts to feed schoolchildren with Lunchtime exhibition curator Jesse Smith.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.