Happy Birthday, Dr. G!

Memory, materials, and the history of science in the Eugene Garfield Papers.

Memory, materials, and the history of science in the Eugene Garfield Papers.

In my household, there is a constant tension between two parties. One is committed to periodic decluttering; the other advocates holding onto stuff for its unforeseen utility. Our debates about what to keep and what to release often get quite heated, especially around the start of the new year. To protect the innocent, I am not going to name names.

If you’ve struggled with cohabitants on this front like me, you are in good company. Collecting institutions like the Science History Institute routinely wrestle with decisions about what to preserve and what to let go. These decisions have consequences for the well-being of museums and libraries, just like they do on the home front. They constrain what is remembered and forgotten, both by individuals and collectives.

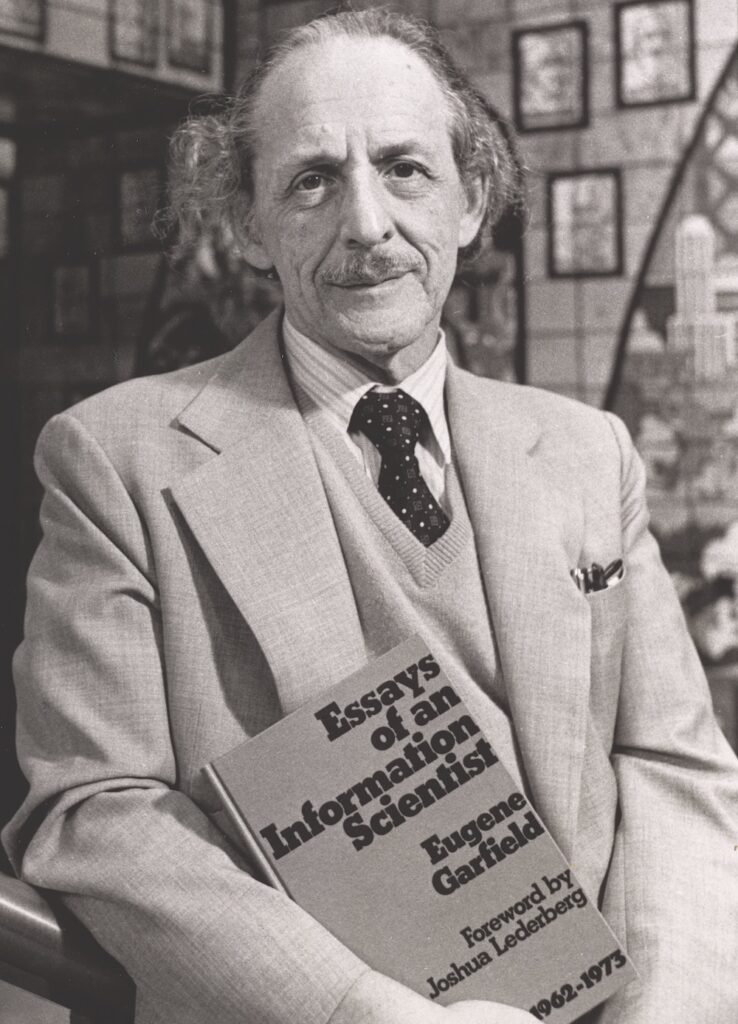

I was struck recently to find an explicit discussion of these dynamics in the 1997 oral history interview Robert Williams conducted with Eugene Garfield (1925–2017). Garfield was a pioneering researcher and businessman in the field of scientometrics, the quantitative analysis of scientific publications. Focused on patterns in citation data, Garfield’s key innovation, the Science Citation Index (SCI), linked journal articles in ways that were similar to what Google PageRank would later do for websites. In the middle of an exchange about the early days of his company, which became the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI), Garfield paused to describe the stuff laying around his office.

I love this exchange because it highlights the importance of physical aides to the working of memory. But it also casts a curious light over the materials that were acquired by the Institute’s archives in 2009 and 2018. Comprising print, photographic, audio-visual, and digital materials, the Eugene Garfield Papers are incredibly rich and heterogenous. They range over subjects as diverse as molecular biology, dry cleaning, impact factors, and jazz. They are simultaneously a portal to another world and a means of understanding the present. I started thinking, what might the collection have revealed if Williams had gotten through to Garfield before he started throwing materials away? Why did Garfield hold on to the things he did? And how can his collections enrich memories and histories of science?

These questions bubbled vigorously to the surface for me the other day when I stumbled upon a colorful assemblage of birthday cards commemorating Garfield’s 75th birthday. These messages, sent and received in September 2000, richly preserve the memories Garfield’s friends, family, and colleagues had about him. They bump up against and constrain the claims of his own memory, helping historians work toward a fuller picture of what this pivotal period in the development of algorithmic culture felt like to those who were involved.

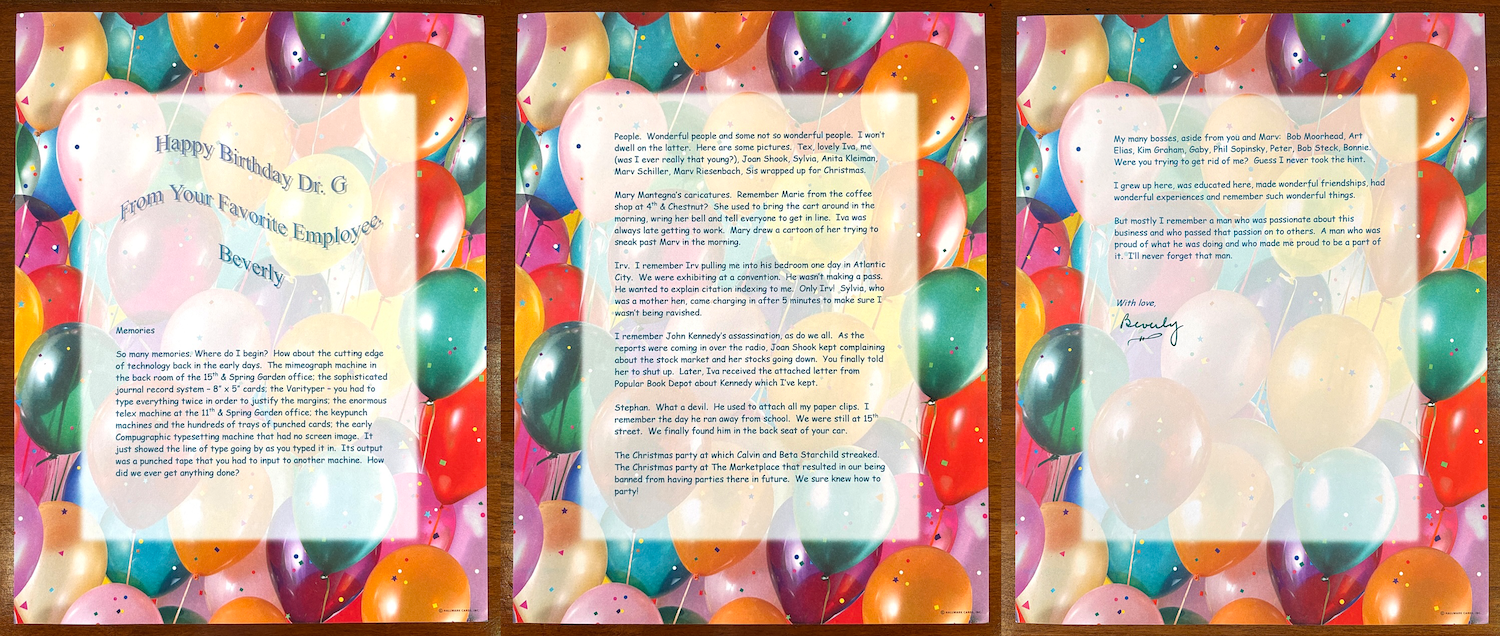

“So many memories. Where do I begin?” That’s how Beverly Bartolomeo, Garfield’s first full-time employee, opened her three-page letter. Meandering through technologies, labors, people, politics, and celebrations, her memories pull back the curtain on numerous lives at the ISI and their intersections.

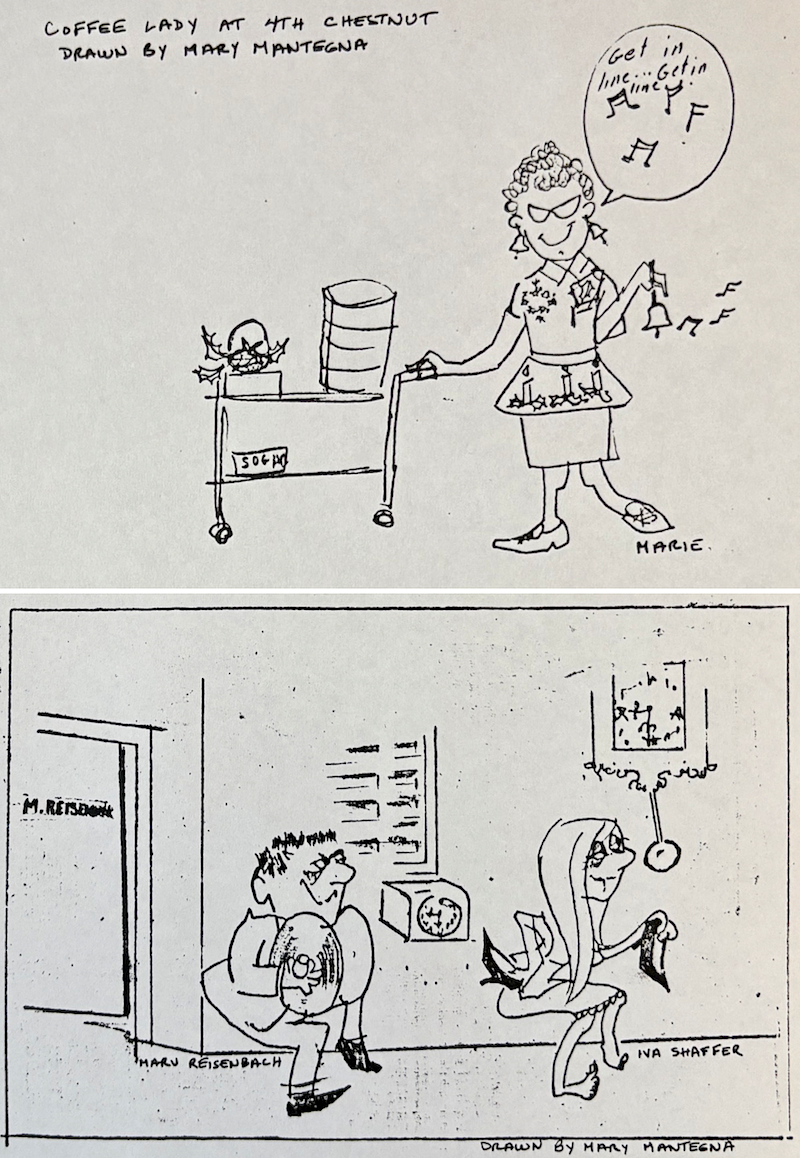

Bartolomeo’s message is especially well documented: along with her letter, she included a miniature archive of photos and clippings that help us see life at the ISI through her eyes.

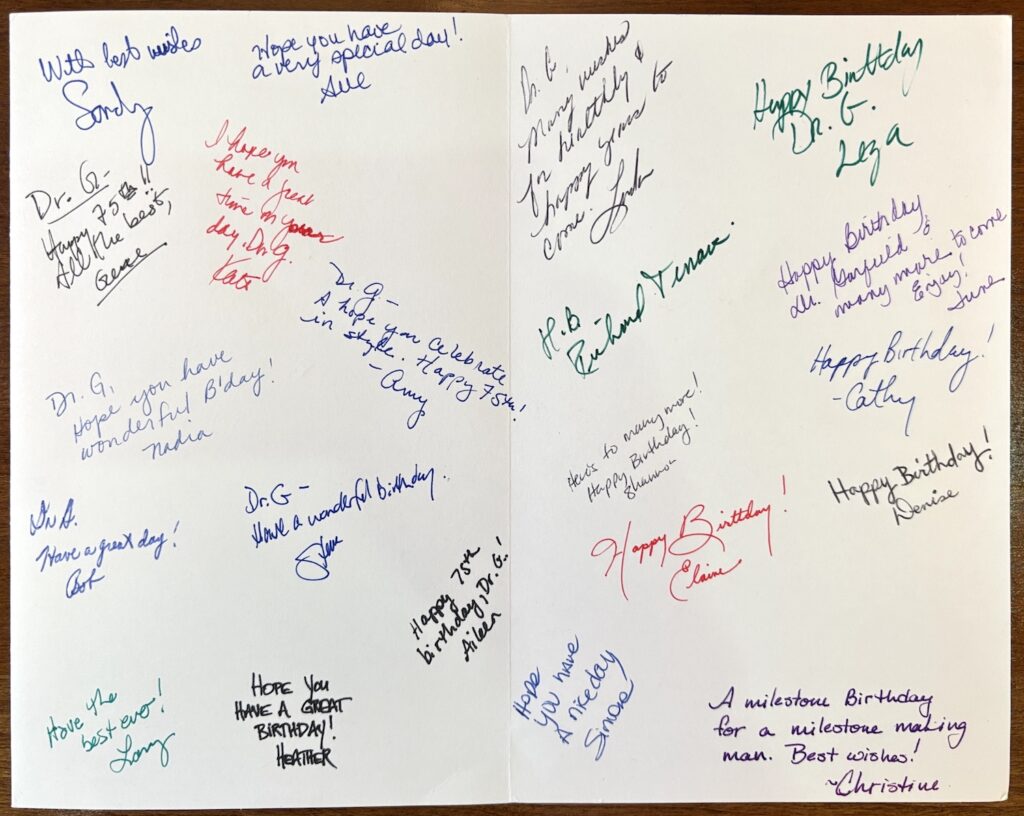

A group card signed by the staff of The Scientist—Garfield’s pet publishing venture—shows that others at the ISI held “Dr. G” and his 75th milestone at greater distance. “H.B.,” says one; “With best wishes,” another; “Hope you have a nice day,” a third is signed. Garfield’s intensive management style, reportedly, was not everyone’s favorite.

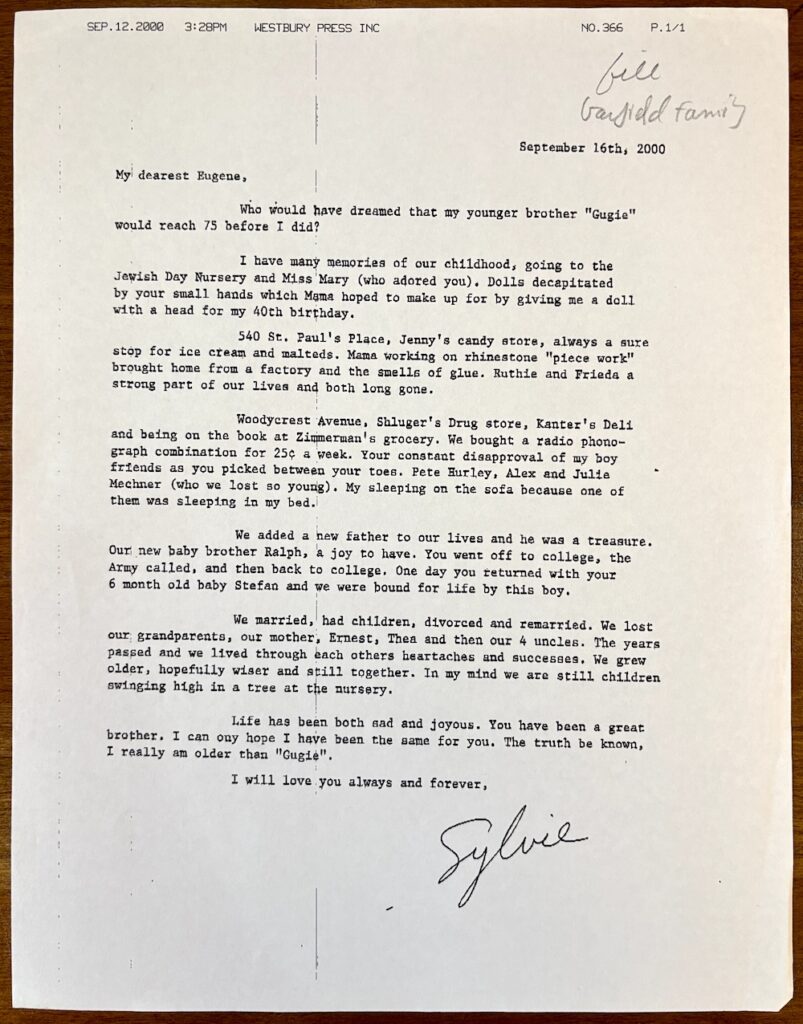

Sylvie Garfield called her brother by a different name. “Who would have dreamed that my younger brother ‘Gugie’ would reach 75 before I did?” Apparently, she felt he still had a lot of growing up to do. Detailing their early life in New York and family relationships, her memories extend and enrich those contained in Garfield’s oral histories and editorials.

Garfield was diligent about replying to the birthday messages he received. His papers also include numerous letters and emails he composed in response to those who sent their regards. Some use the occasion as a jumping-off point to till further memories of colleagues and friends; others, as an opportunity to get more scientometric work done. We learn that Garfield collected these materials in a box “with a turtle on top.” Birthday cards, unlike lecture slides on information science, were apparently worthy of preservation in his view.

Garfield created the ISI because he thought easier access to citations could help researchers better understand the scientific community and how it had developed over time. His turtle-topped box of birthday cards—surprising in its sentimentality but certainly not accidental—provides a complementary lens.

Explore the history of science behind U.S. efforts to feed schoolchildren with Lunchtime exhibition curator Jesse Smith.

Unwrapping the mystery of a Styrofoam Santa in our collections.

New World ingredients in Old World dyes.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.