How to Judge a Book by Its Cover

What book bindings teach us about readers of the past.

What book bindings teach us about readers of the past.

Despite living in a seemingly technology-defined world, all-consumed by Tik Tok, Chat GPT, and the newest generation of iPhone, it’s still reasonable to say that most of us have had the experience of holding (and maybe even reading) a physical book. In the same way historians will someday propound upon what AI and social media indicate about our society today, bibliographic experts examine the construction of books to draw conclusions about the people of any given period. This concept is referred to as material culture. Book bindings can indicate broad trends in literacy and information dissemination or provide specific insights into provenance—the record of who owned that book.

This is the first post in a series of explorations into the material culture of… you guessed it, books! In this series, we’ll look at examples from the Science History Institute’s Othmer Library that illustrate the craftsmanship and construction techniques of bookbinding, the properties of paper, the effect of the invention of the printing press, and more!

Let’s start with a crash course in the basic anatomy of a book. If we are conceptualizing a book from a Western perspective (excluding scrolls and tablets, for example), almost any book is made of three basic pieces: the text block, binding, and covers.

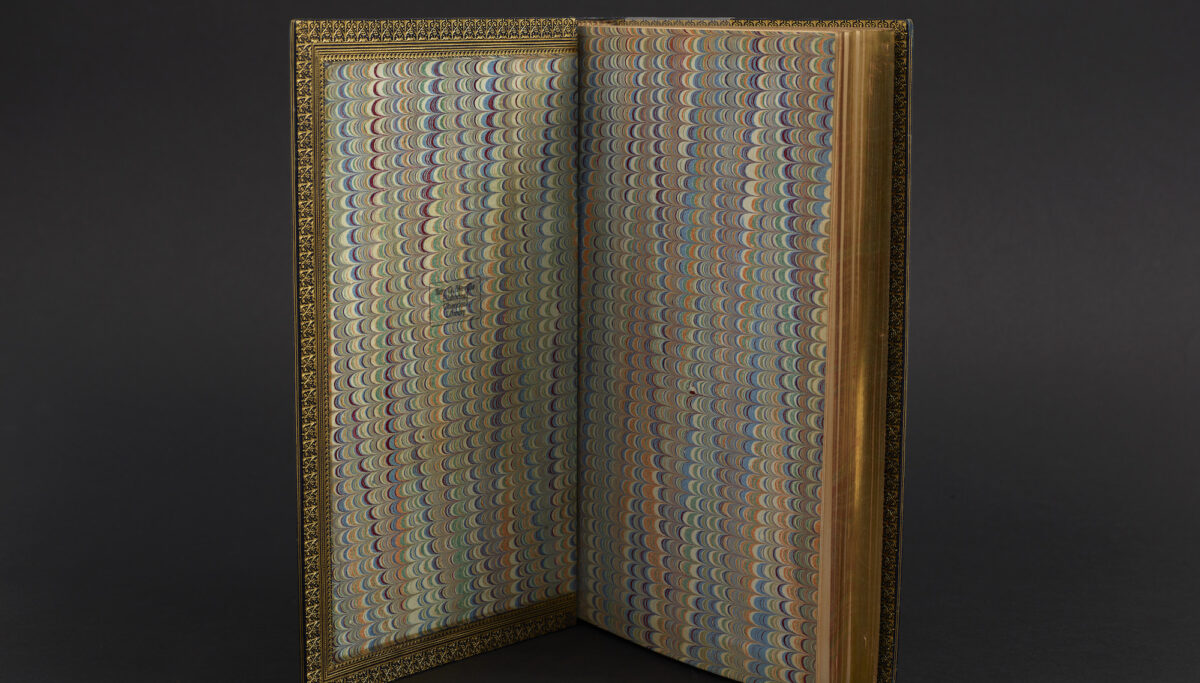

A text block is a group of writing or drawing substrates—paper, parchment, or papyrus—folded and/or stacked together into sections (also called quires, signatures, or gatherings: book people generally have a hard time sticking to one term). Endleaves (also known as endpapers or endsheets) are extra sheets of folded paper or parchment attached to the beginning and end of the text block. The endleaves help to protect the text block and attach it to the cover; the leaf attached to the inside of the cover is known as a pastedown and any extra blank leaves before and after the text block are called flyleaves.

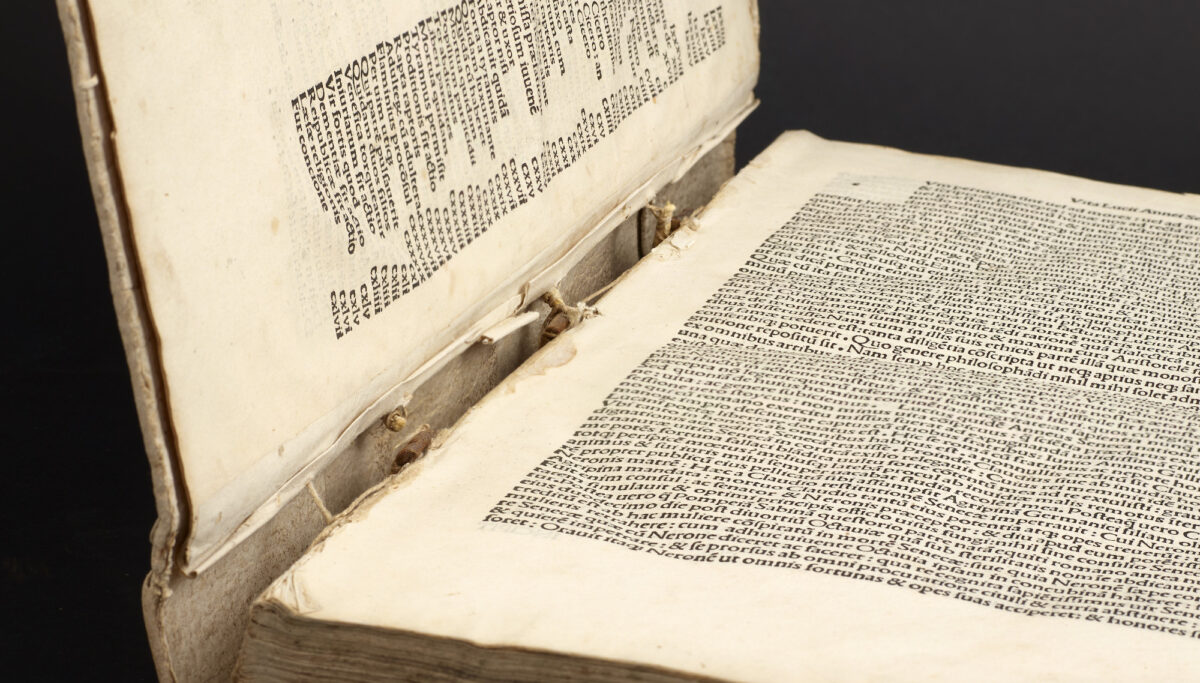

The binding is the system used to join sections of the text block to each other and create the book’s spine. In the sturdiest books, each section is sewn through its fold and the sewing is looped around a support at even intervals. Supports can be made of leather, parchment, linen cord, or woven tapes. The free ends of sewing supports are known as slips and attach the text block to the book’s cover boards. Less durable books may use an abbreviated sewing method, such as bypass sewing (skipping supports), 2-up sewing (sewing two sections together), stabbing or stitching (passing a support or sewing through the book’s margin), or adhesive binding (the spine is glued together, no thread is used).

Early binders often added additional sewing supports at the head and tail of the spine, known as headbands or endbands. Today modern bindings mimic medieval hand-sewn headbands with glue-on endbands. After a text block is sewn together, its spine is consolidated by coating it with an adhesive (traditionally animal glue) and rubbing it flat to fully adhere the sections together.

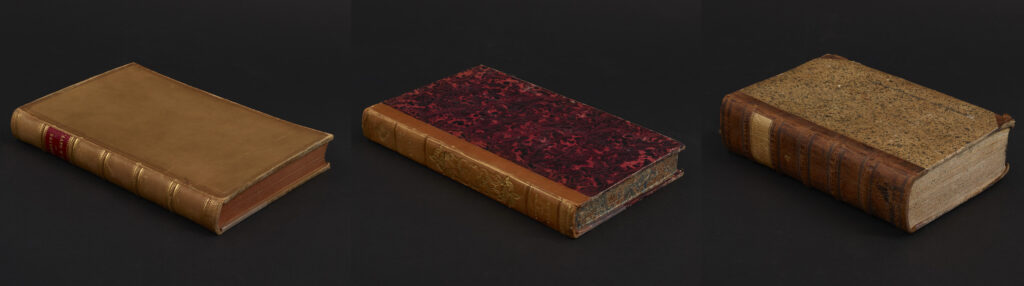

Book covers protect the text block and make the book easy to shut and store. Covers can be made from wood, pasteboard, pulpboard, paper, or parchment. Wooden book boards are laced on to the text block by passing the slips of the sewing supports through tunnels or channels in the boards. If the boards are paper based, the slips are glued on. Once attached to the textblock and binding, boards are covered in cloth, patterned paper, leather, or a combination. For example, books may be fully bound with leather, or they can be “half” bound, or “quarter” bound.

Book covers often have various decorative elements, such as furniture, elaborate metal pieces attached to the covers, sometimes bejeweled; ties or clasps, metal or ribbon pieces that connect the front and back covers; tooling, patterns stamped into leather, sometimes gilt; and inlays, embedded leather or other materials. Decorating a book is known as finishing.

Now that you’ve learned a bit of terminology, let’s examine a few specific bindings in our collection to draw some conclusions about their previous owners and the context in which they were created.

Believe it or not, there was a time (think early Middle Ages), where, relatively speaking, there simply weren’t that many books. Written and bound by hand, books could take years to finish. Books were primarily crafted for religious institutions or members of elite social classes. Even if laypeople had access books, few of them could read. It wasn’t until the end of the 15th century, after the invention of the Gutenberg press had revolutionized book production, that enough books existed to introduce a new system for storage. Before then, books were laid supine, with the front cover facing out, not stored on end with their spines facing out, as we are accustomed to today. Metal fixtures called bosses can indicate how the book was stored. These metal knobs slightly elevate the book from the table surface, so that the book wouldn’t lay directly on its leather covers.

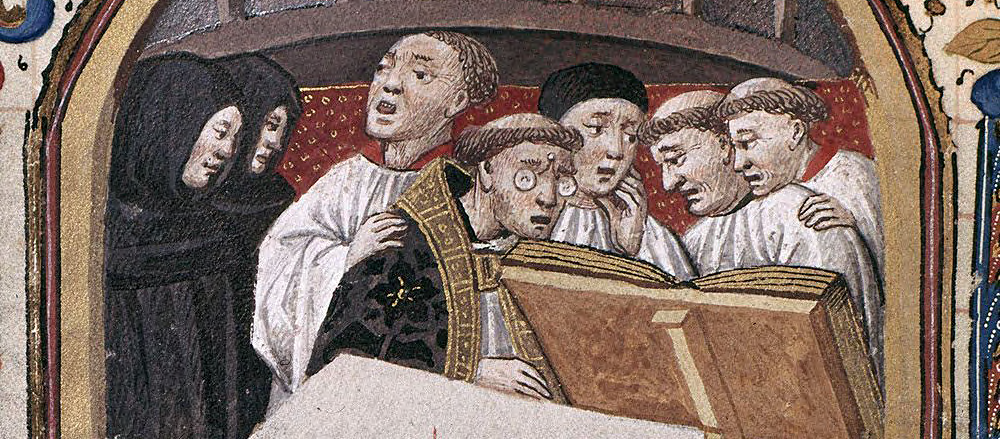

A large book may indicate a wealthy owner because of the time and cost to produce such a work, or that the book was intended for use by more than just one person. Group reading was common in the Middle Ages; for example, it’s common to find religious texts or choir books in large formats that would have been conducive for a group of priests or the congregation to read from.

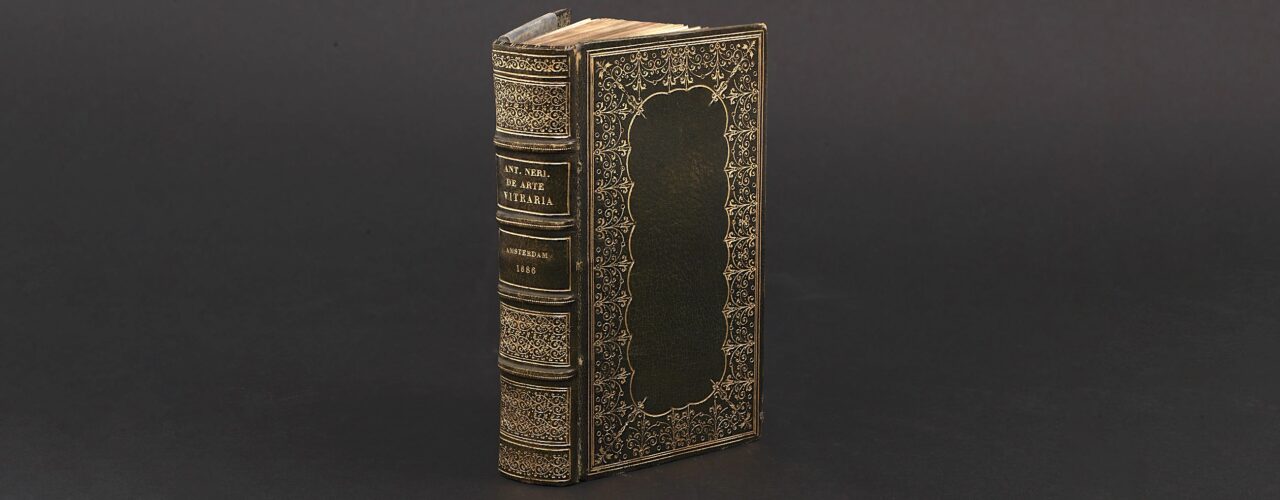

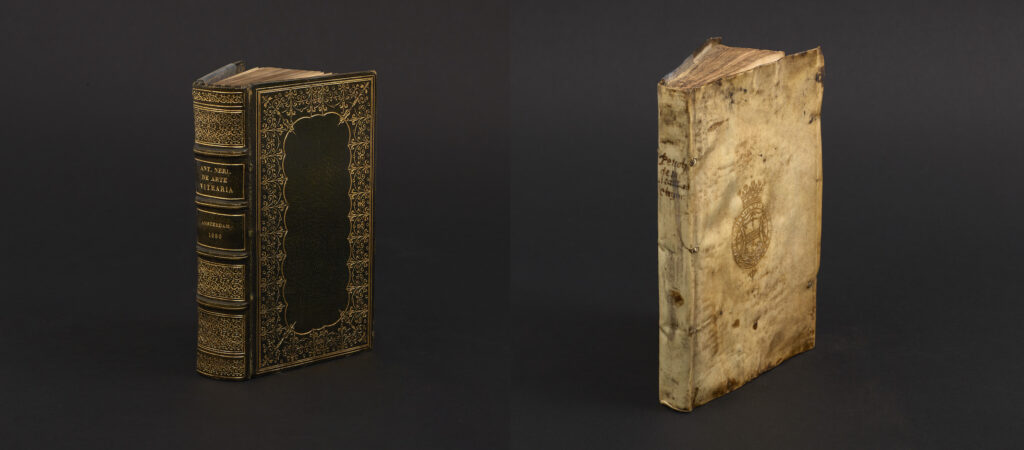

Bindings that are elaborately finished, such as the examples below, offer another window into former owners’ motivations and circumstances. An owner who opted to sumptuously bind a book may have done so out of reverence for the content, but more likely was engaging in an act of conspicuous consumption. A library of elaborately decorated books was (and remains) a status symbol of wealth and intellect. De Arte Vitraria (below, left, 1686), is no longer bound in its original case, perhaps because it was damaged or its subsequent owner found it to be uninteresting. A later 19th-century owner opted for the work to be rebound in full dark-green Morocco leather, a goatskin leather with a prominent grain pattern popular in fine bindings after the 18th century. The covers are decorated with broad filigree dentelles and inner dentelles, all richly gilt, including the edges and spine.

This owner clearly placed high value on the appearance of their books and had the financial means to customize their collection to their liking. In contrast, Tractatus Varii (above, right, 1594) is bound in its original limp vellum covers (“limp” indicates that no boards were used). The less showy, flexible, and lightweight binding indicates that this book may have been intended for intensive use, i.e., study and reading, and for easy transport. Though this book clearly had practical use, we can also infer that this owner wanted to make their ownership known due to the gilt armorial crests present on each cover.

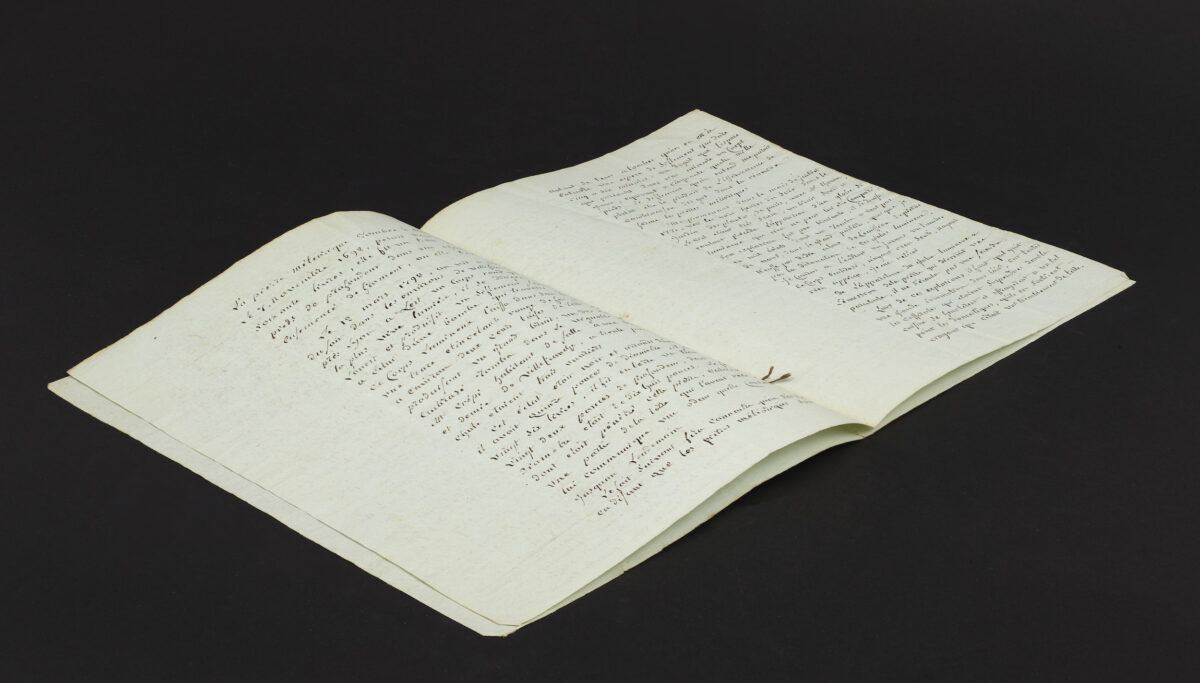

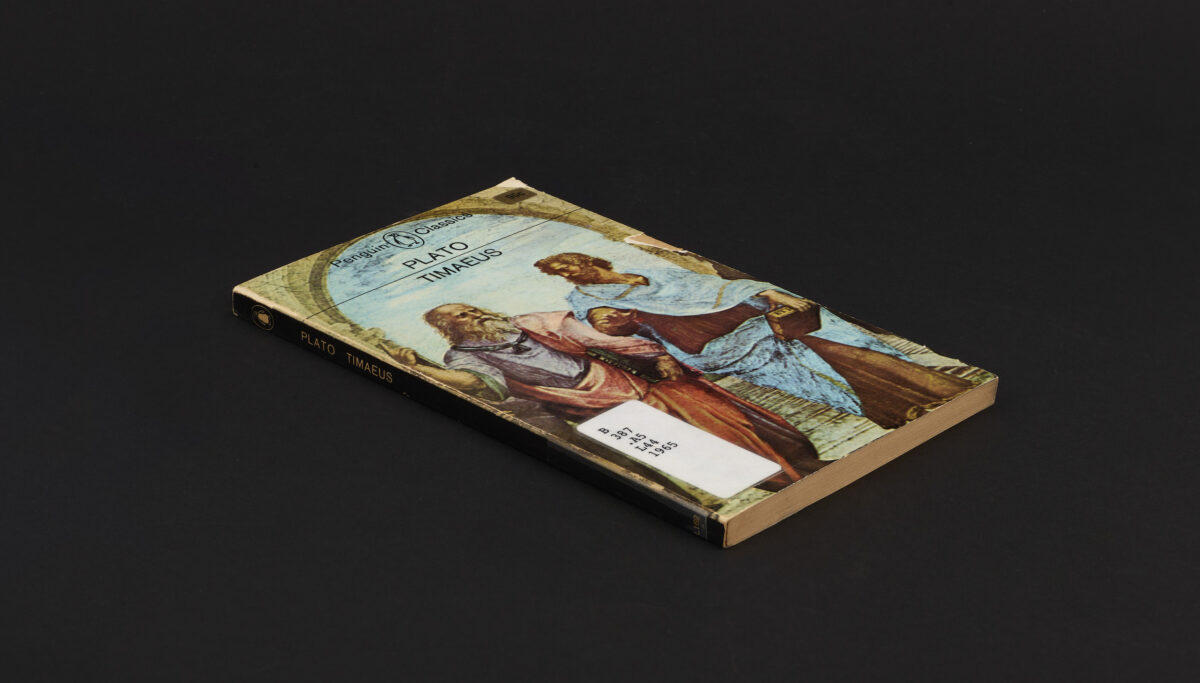

Explore the slide show below for more examples of limp coverings, a cheap and flexible binding option akin to today’s paperbacks. Limp bindings were produced as early as the 14th century and were especially popular for use in traveling accountants’ notebooks during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Limp bindings using vellum or parchment began to decline by the 19th century, and limp leather bindings came into vogue especially for pocket bibles and notebooks through the 19th century. In 1935 the first modern paperback was introduced by Penguin publishing house.

With the ability to print quickly, thanks to the invention of the Gutenberg press in the West in 1436, the cost of book production went down, and reading gradually became more accessible and subsequently, a popular activity. Fast forward several hundred years to the period of early 19th-century industrialization. Books were in high demand among upper- and middle-class folks; literacy rates were high among white men, and growing among white women, in Europe and the United States. Reading had become a common pastime, and printed materials were the established method for spreading news and information. It was impractical to keep up with the demand without the mechanization of the bookbinding process. Enter, the case binding. This simplified the fast construction method, in which covers are glued directly to a consolidated text block, streamlined the book production process.

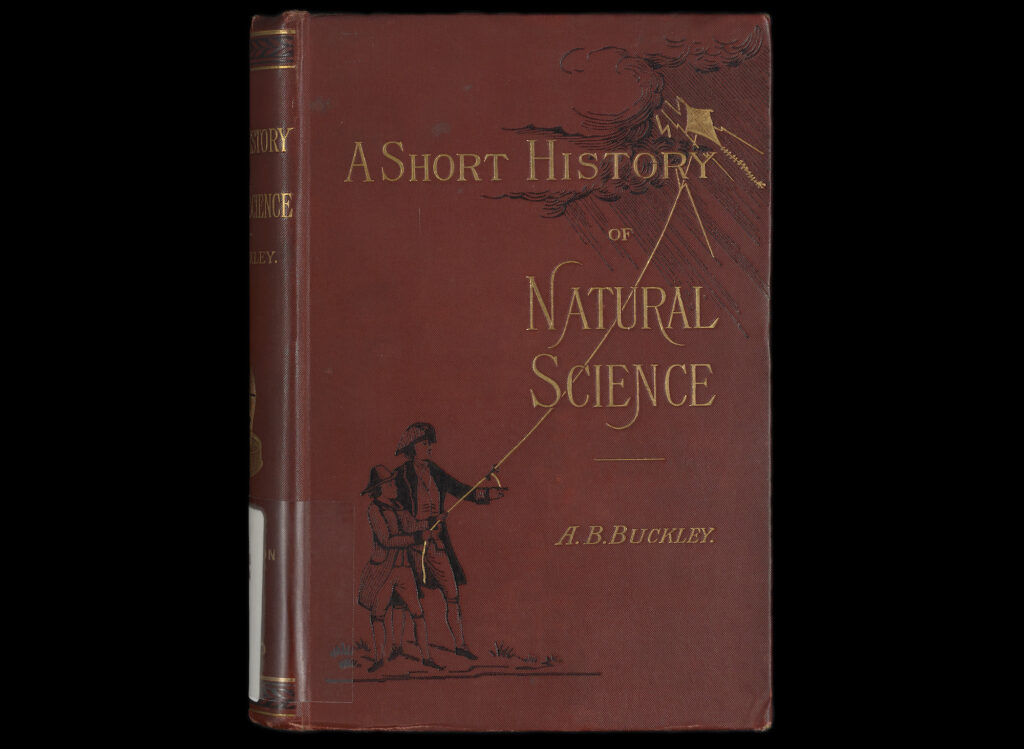

Thanks to new binding methods, such as the case binding, publishing houses gradually grew into flourishing and powerful companies. By the 1830s, publishers began to produce books in novelty cloth-bound case-bindings with varying levels of decoration. The work below, A Short History of Natural Science (1894) is an example of an elaborately decorated publisher’s binding and is a book written by a woman for children—a true sign of the times! Cloth coverings became immensely popular as they were cheap, robust, and easy to customize. They remain a timeless and popular board covering to this day.

There have been innumerable methods of bookbinding across the world and throughout history. Each system of construction is intentional, whether serving a practical purpose or embodying a social trend. Though only a few Western examples were given today, you can explore more bindings through the Science History Institute Digital Collections.

In pursuit of something memorable and meaningless.

How does a museum and library negotiate biography, civics, and the history of science?

Searching for the cats hiding in our collections.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.