Ladies Who Lab: Lesser-Known Women in Science, 1920–1970

Highlighting the work of 20th-century female scientists in our library collection.

Highlighting the work of 20th-century female scientists in our library collection.

I recently read—and loved—Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus. Set in the 1960s, it tells the story of Elizabeth Zott, a brilliant chemist who faces discrimination in the workplace due to her gender. Zott inadvertently lands a role as a cooking show host after she is unfairly fired from her research post. Through her television platform, she inspires women across the country to be more confident in themselves and dismantles the male-superiority complex. She sets a precedent that women can achieve anything they set their minds to.

Though Lessons in Chemistry is a work of fiction, there were many real-life “Elizabeth Zotts”—women who were successful, if not well-known, scientists despite cultural circumstances.

While identifying books to digitize for the Science History Institute Digital Collections, I happened across several women in STEM who I hadn’t previously known. I was browsing a list of more than 300 books in the Othmer Library published in the year 1928 (because these books entered the public domain on January 1, 2024), when I began to pick authors who I suspected were women. I counted only four.

These four female authors I identified are not well known, despite leaving legacies and hearty contributions to their scientific fields. It seems the implicit standard for a female scientist to become a household name is a Nobel Prize à la Marie Curie, the archetypal woman in science. So below I offer brief vignettes of the lives of these four Nobel Prize-less, yet impressive and deserving contributors to science, celebrating the true lives of women scientists in the 1920s and beyond.

Dr. Anna Marie Farnsworth was born on July 19, 1895, in the small rural village of Latour, Missouri. She began studying science at Central Missouri State University before transferring to the University of Chicago, where she graduated in December 1918 with dual bachelor’s degrees in physics and chemistry.

Farnsworth, who went by “Marie,” went on to earn a PhD in chemistry from the University of Chicago in June 1922. After her graduation, the newly 27-year-old Marie moved from Chicago to New Jersey to begin working for the Nonmetallic Minerals Experiment Station, part of the Bureau of Mines of the Department of the Interior. After a short period with the Bureau, she settled in Greenwich Village in New York City, where she began as an instructor in chemistry for Washington Square College at New York University. At NYU Dr. Farnsworth published her textbook The Theory and Technique of Quantitative Analysis (1928), which can be found in our collection.

In the mid 1930s Dr. Farnsworth became a research chemist at the Fogg Art Museum, where she developed a keen interest in archaeology. While there, she pioneered the field of archaeological chemistry. In 1938 the American School of Classical Studies at Athens asked Dr. Farnsworth to join an archaeological dig in Agora, Greece. She was one of the first chemists ever asked to accompany an excavation.

In 1941 Dr. Farnsworth accepted a position with the Metal & Thermit Corporation in Jersey City, New Jersey, where she worked until her retirement in 1961. Despite her career in industry, she continued to pursue her passion for archaeology. She published on topics such as the spectroscopic study of glass, the techniques of black Attic glaze and 5th-century intentional red glaze, the cleaning of bronze, the metallographic examination of ancient zinc from Athens, the analysis of Corinthian pigments, and the composition of Athenian cement.

She returned to Greece to work on archaeological digs in Corinth from 1958 through 1964. After her final expedition, she went on to teach a course titled “Science for the Archaeologist” at the University of Missouri–Columbia. In 1980 she was awarded the first Pomerance Award for Scientific Contributions to Archaeology given by the Archaeological Institute of America.

According to a June 1991 interview given by Dr. Farnsworth’s niece to The Holden Progress, Marie Farnsworth was a private person with a great love of reading. She loved nature and children, and strongly believed in education. “She didn’t learn housework like most women of her generation . . . Marie had set her goals early and followed her dream,” her niece said.

Dr. Marie Farnsworth died on June 8, 1991, at the age of 95.

Dr. Katherine Snodgrass lived a short but accomplished life. She was born on May 9, 1893, in Marion, Indiana. According to the 1890 census, the town had a population of only 8,700 at the time of her birth. After graduating from high school, she left her small-town life and moved to the Philadelphia area to attend the all-girls Bryn Mawr College. In 1915 she earned her degree in economics.

After graduating Dr. Snodgrass moved to New York City. She earned her master’s degree in economics from Columbia University in 1918 while working as a statistician for the State Charities Aid Association, and then settled in a home on the quaint Grove Street in the West Village. She worked as a statistician for the War Industries Board in 1918 and 1919; as a research assistant for the Federal Reserve Board from 1919 through 1922; and in 1923 as an associate editor for the New York Journal of Commerce.

In 1924 Dr. Snodgrass moved to California to become a research associate for the Food Research Institute at Stanford University. She worked there from 1924 through 1929, earning her doctorate from Stanford in the last two years. It was in this role she wrote and published Copra and Coconut Oil (1928), a study of the economics of coconut oil and its growth in popularity in the 1920s, which can be found in our library.

In 1930 Dr. Snodgrass was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to “make a study of the dietary fats of Northern Europe, with particular reference to the displacement of dairy fats by vegetable fats, being a study in the economics of food substitution.” Dr. Snodgrass traveled to England in September 1930 as part of her research. According to a September 25, 1930, article in the St. Cloud Times, immediately upon her return to the U.S., she visited her sister in Minneapolis and checked into the University Hospital for an “acute nervous ailment.” Sadly, she died by suicide at the hospital.

Dr. Snodgrass overcame humble rural beginnings and lack of opportunities due to her gender. She traveled, published many works on economics and chemistry, and received prestigious professional accolades.

Dr. Marguerite Griffith Tyler was born in Owensboro, Kentucky, on February 25, 1881. Her father was a military commander, so her early life was spent moving between Army posts across the U.S. and even the Philippines. In a 1936 newspaper interview, she says her childhood hobbies included skating, skiing, horseback riding, hunting, and other outdoor sports.

Dr. Tyler was educated at her own pace with the aid of governesses and tutors for much of her upbringing. According to Marguerite, this method of schooling taught her “to study for herself instead of for the teacher.”

Salt Lake City High School was the first public school she attended, and she enrolled at the College of Washington in Pullman, Washington, at the age of 15 before attending the University of Michigan. In a 1924 alumni survey conducted by the University of Michigan, Dr. Tyler spoke highly of her undergraduate education:

She earned her bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Michigan in 1903.

Following her graduation, Dr. Tyler taught at the University of Cincinnati before attending the University of Chicago, earning her master’s degree in chemistry by 1910. Degree in hand, Dr. Tyler went on to hold various postings across the country, including botany instruction at Washington State College and science instruction for nursing students at Lewiston State College in Idaho. She moved to New York City to complete her doctorate at Columbia University between 1927 and 1929. Her doctoral thesis, “A Quantitative Study of the Influence of Acetate and Phosphate on the Enzymic Activity of the Amylase of Aspergillus Oryzae” (1928), is in our library collection.

Dr. Tyler taught at the all-women’s Limestone College in South Carolina from 1929 to 1933, and then at the University of Kentucky from 1933 to 1935 before becoming a professor at the all-women’s Athens College in Alabama in 1936.

The remainder of Dr. Tyler’s life is less well-documented. According to an article in The Lewiston Tribune, she left Athens College in 1941 for Oak Ridge, Tennessee, to work on the Manhattan Project. She died on April 2, 1969, at the age of 88 in Owensboro, Kentucky.

Dr. Marguerite Griffith Tyler’s evident ambition was at odds with her gender and the time in which she lived. She undoubtedly battled discrimination, even from her family. In an interview in the Athenian, the Athens College student newspaper, she remarked, “[I] had never expected to be a teacher; [I] had always wanted to be a lawyer. [My] family, however, discouraged this ambition.”

Yet Tyler made the most of her career as a teacher and even felt empowered to critique unfairness as she saw it. In her response to the University of Michigan’s alumnae survey, she states, “the University of Michigan has never given women a chance on its faculty as I see it compared to other colleges.” To Dr. Tyler, life as a teacher was not a tame existence. “It has been most adventurous, dangerous, and exciting, due to the fact, in [my] opinion, that [my] work was in the field of science.”

Dr. Lotta Jean Bogert was born in South Dakota in 1888 and grew up in Colorado and Missouri. When she was 12 years old, her father passed away and her family relocated to New York State. She had a very active childhood, telling the San Rafael Daily Independent Journal in 1966, “I was always athletic. I played basketball and tennis as a girl. Sports are wonderful, providing you are knowledgeable about them. The only ones who don’t like sports are those who don’t understand the games.”

After high school she and her brother enrolled at Cornell University. Their mother passed away shortly after the siblings began college, but scholarships made it possible for Lotta and her brother to continue their educations.

Dr. Bogert earned her bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1910. She then attended Yale University to study biochemistry with Lafayette Mendel (1872–1935), the pioneering scholar of nutrition sciences. She earned her PhD from Yale in 1916 with her thesis, “The Regulation of the Blood Volume after Injection of Saline Solutions: Studies of the Permeability of Cellular Membranes.”

Dr. Bogert then became the first woman to hold a regular faculty position at the Yale School of Medicine. She conducted medical research and was an instructor in experimental medicine for three years before pursuing opportunities as a professor of food economics and nutrition at Kansas State University; a research chemist at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit; and a researcher at the University of Chicago Medical School. It was during this period that Dr. Bogert began writing textbooks for first and second-year college students, including Fundamentals of Chemistry: A Text-Book for Nurses and Other Students of Applied Chemistry (1924), which is part of our library collection.

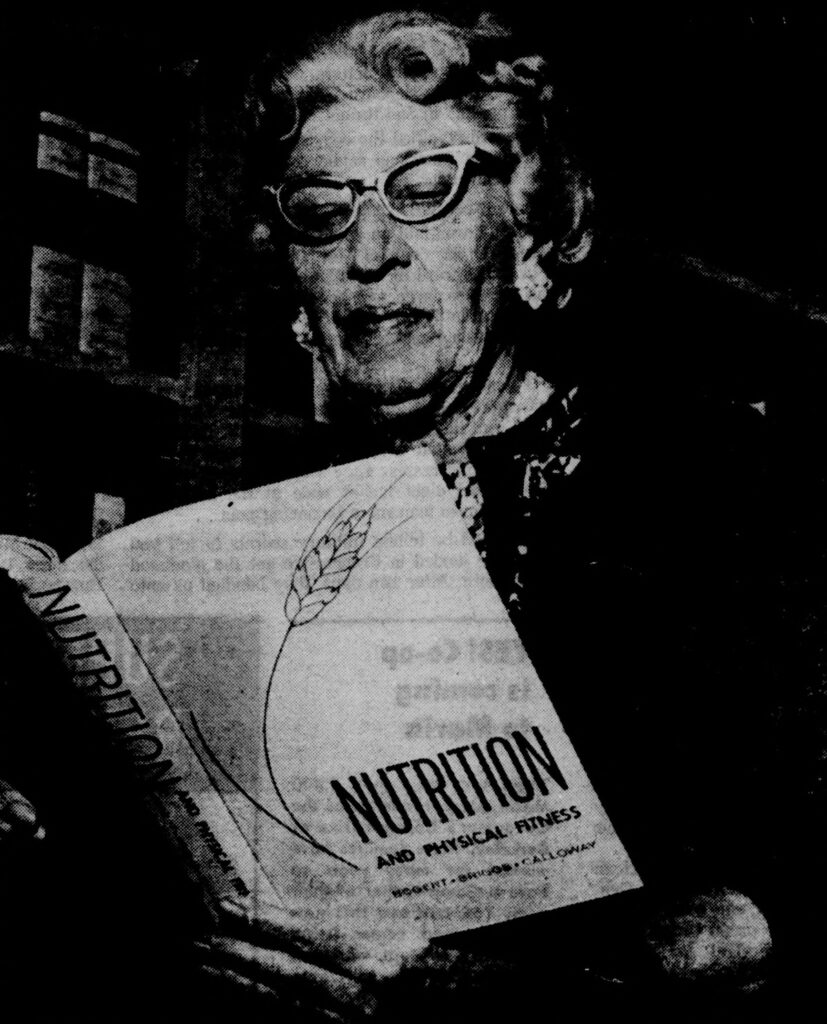

Dr. Bogert’s work centered on health, well-being, nutrition, and exercise. Her most popular work, Nutrition and Physical Fitness (1931), had nine subsequent editions. She also wrote articles to educate the public about nutrient intake and the nutritional development of children, including “Making a Menu to Suit All Ages” and “Adapting Food to Different Ages,” which were featured in National Parent-Teacher Magazine in 1935. In 1939 she moved from New York City to Berkeley, California. Dr. Bogert died in 1970.

To learn more about impressive but unsung women like Drs. Farnsworth, Snodgrass, Tyler, and Bogert, please check out Women Do Science, Too! in our Stories by Topic section.

Featured image: Wilson College Chemistry Club, group photograph of the members of the school’s chemistry club, ca. 1937.

Science History Institute

More and more digital research tools are helping to answer even the smallest collections questions.

In pursuit of something memorable and meaningless.

How does a museum and library negotiate biography, civics, and the history of science?

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.