Patents, Papers, and Passports: The Scientific Odyssey of Fritz Hochwald

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

How a Jewish scientist’s intellectual property became a lifeline in his journey from Nazi Europe to the United States.

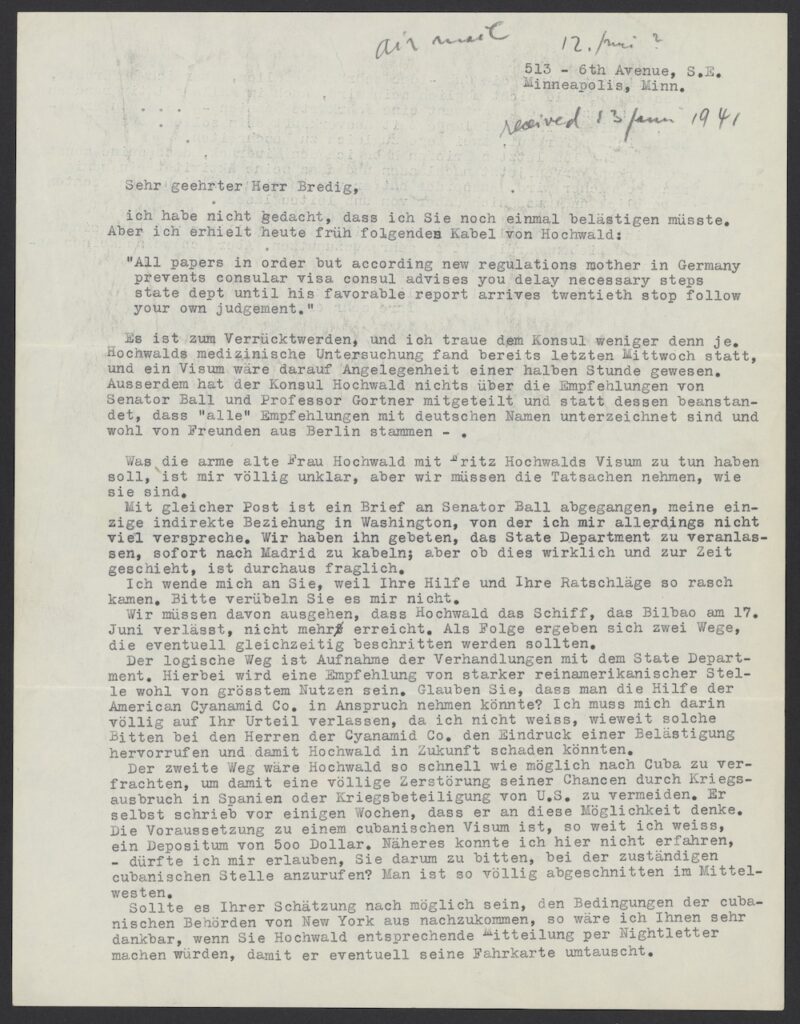

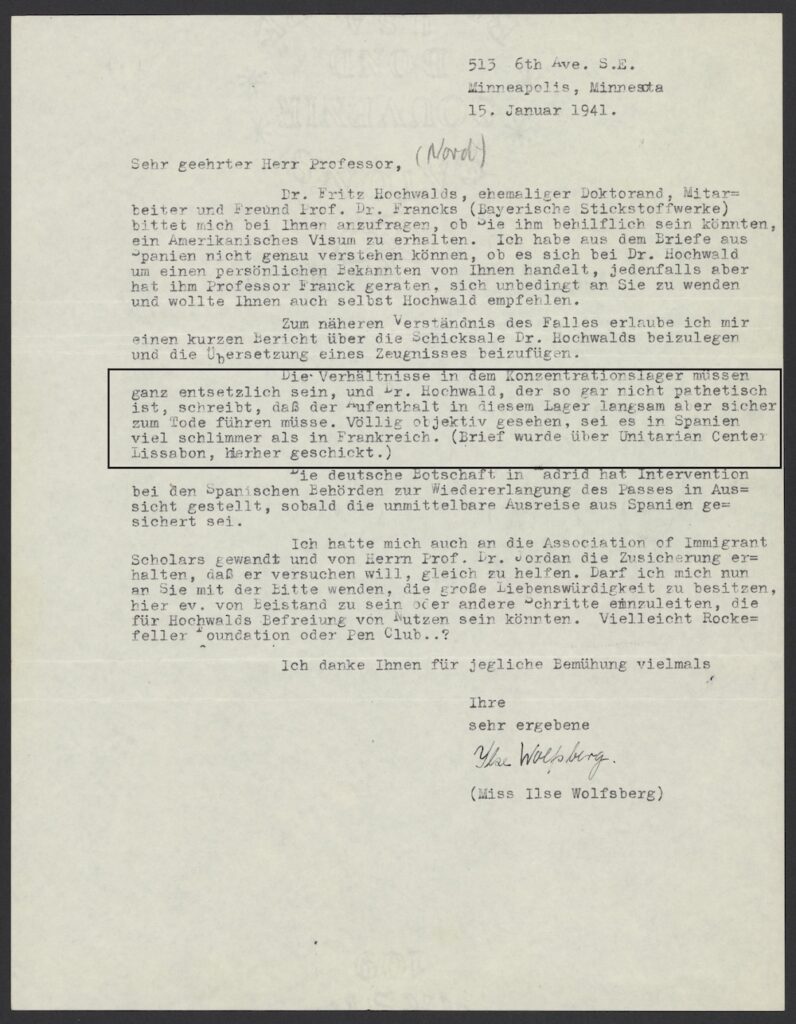

In January of 1941, Ilse Wolfsberg, the fiancé of Fritz Hochwald, contacted Hochwald’s colleague Max Bredig in a desperate attempt to help Fritz safely immigrate to the United States. “I don’t know where else to turn for advice,” Wolfsberg wrote to Bredig. A Jewish scientist turned patent attorney, Hochwald had been captured while attempting to flee the terrors of Nazi Germany, and it was up to Wolfsberg and Bredig to save him. What followed was an odyssey of scientific immigration, one that intertwined legal processes with an emotional journey of personal salvation.

Coming into my work as an intern with the Science History Institute, I had no idea that my collections work would take me down a path of scientific immigration, combining my interests as an undergraduate at Villanova University. I come from an ancestry of immigrants: my grandfather obtained his American citizenship after winning the Dominican National Lottery, receiving the funds to afford travel to Ellis Island in the 1930s.

From this background, I’ve centered much of my undergraduate research on studying American immigration, with an emphasis on legal history. Thus, this background gave me a different perspective in viewing the Institute’s collections. I was interested in how scientists could use their work and intellectual property to aid in their migration efforts, in effect using scientific discovery as a vehicle for obtaining citizenship.

Fritz Hochwald (1897–1968) had a turbulent life and professional career. He initially worked as a chemist in 1923 before shifting gears to become a patent attorney in 1929. At some point, Hochwald became colleagues with Max Bredig, whose personal papers, as well as those of his father Georg Bredig, are held in the Institute’s archives.

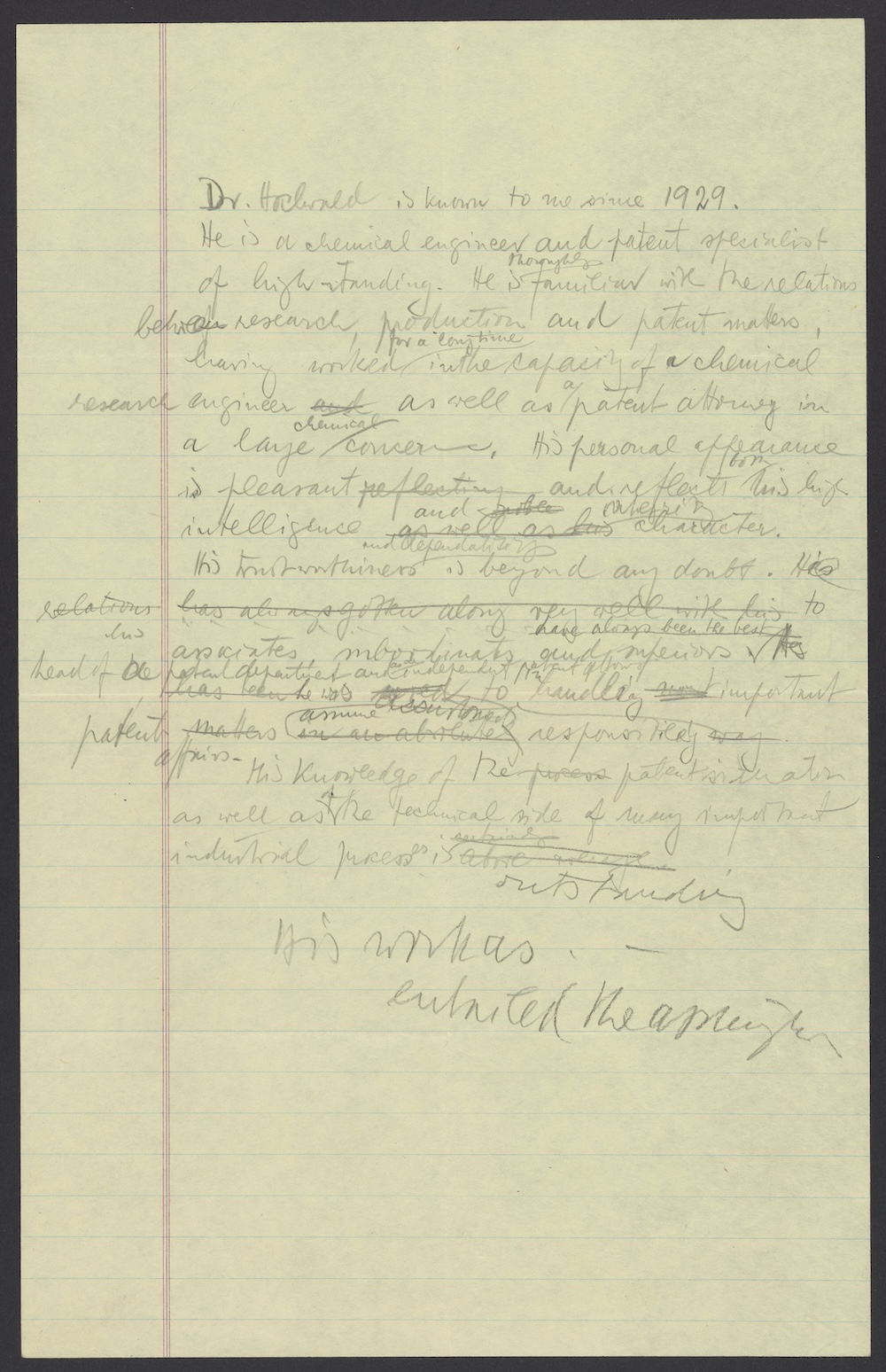

Max left Germany in 1937, ending up at the University of Michigan, where he frequently aided his family and scientific colleagues who sought to immigrate to the U.S. in order to escape the Third Reich’s racist and anti-Semitic program of imprisonment and murder. Hochwald was one such individual, developing a close partnership with Bredig who, in a 1941 draft affidavit, testified that Hochwald’s “intelligence and dependability [are] beyond any doubt.”

Hochwald’s journey began in 1939. He was dismissed from his job as a patent attorney in 1938, due to Nazi rules forbidding non-Aryans in professional roles. As a Jewish man living in Nazi Germany, he knew his life was in jeopardy. In 1939, he was able to leave for Switzerland, but in August of that year, he was arrested while on a business trip in Paris and detained in French camps.

In October 1940, he fled France on foot for Spain, only to be arrested the same month in Barcelona and interned in the Miranda de Ebro Concentration Camp in Burgos, Spain. The camp, originally used to detain Spanish nationals who supported the former Republican government in the Spanish Civil War, was considered, according to Maurice Chauvet, “much worse than any of the French camps.” Upon his capture, Hochwald contacted Max and Ilse to request assistance in obtaining an American visa.

Over nearly three years, Bredig and Wolfsberg contacted 14 different individuals to request affidavits to support Hochwald’s immigration case, including Senator Joseph H. Ball, a Republican senator from Minnesota, and Max Mayer of the American Cyanamid Company, one of the major chemical manufacturing conglomerates in the United States at the time and a company for whom Hochwald had done patent work in pre-war Germany.

Around June 1941, a U.S. immigration official told Wolfsberg that Hochwald’s contacts were so good that he would “live well” in the United States in no time. However, Hochwald’s pilgrimage to the United States was uncertain, as he would have to wait roughly two years to even receive a hearing with the Department of State despite his near-perfect recommendations.

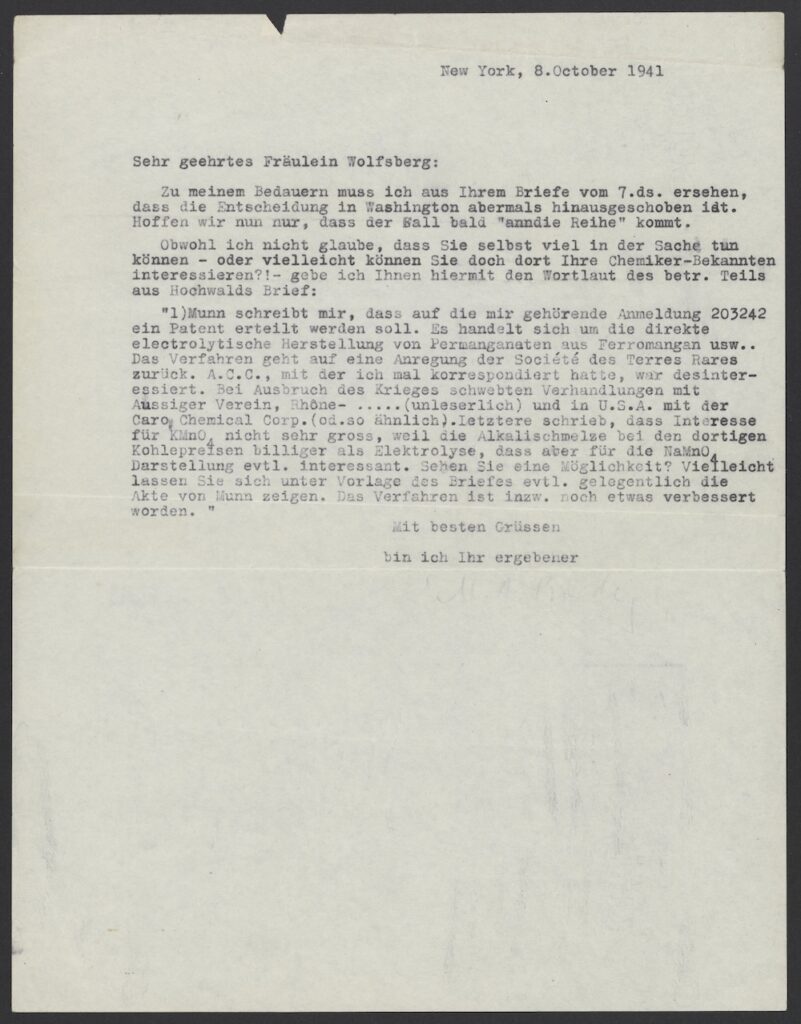

Bredig and Wolfsberg attempted many different routes to expedite Hochwald’s visa status, including using Hochwald’s patent as leverage. In 1941, thanks to Bredig’s assistance, Hochwald’s patent for the direct electrolytic production of permanganates from ferromanganese was approved, though questions loomed about its potential use in Hochwald’s immigration case. In an October 1941 letter to Ilse Wolfsberg, Bredig mentions this possibility, informing her that he will “inquire at [his] company [Vanadium Corporation of America] if there is interest” in Hochwald’s patent with regards to his immigration case.

In fact, there exists a connection between inventorship and patenting and ideas of citizenship and worth, one that legal historian Kara W. Swanson calls the “useful citizen ideal” (Swanson, “Beyond the Progress of the Useful Arts: The Inventor as Useful Citizen”). According to this idea, the immigrant inventor’s “inventiveness” is proof of his or her “ability to assume all citizenship rights and responsibilities.”

It is possible that Max and Ilse attempted to use Hochwald’s patent to boost a potentially weak visa application, appealing to the idea that patent ownership signaled an applicant’s ability to contribute beneficially to his or her new country of citizenship. Ultimately, it is unknown precisely what role Hochwald’s patent played in obtaining his U.S. visa in 1943, nearly three years after his confinement began.

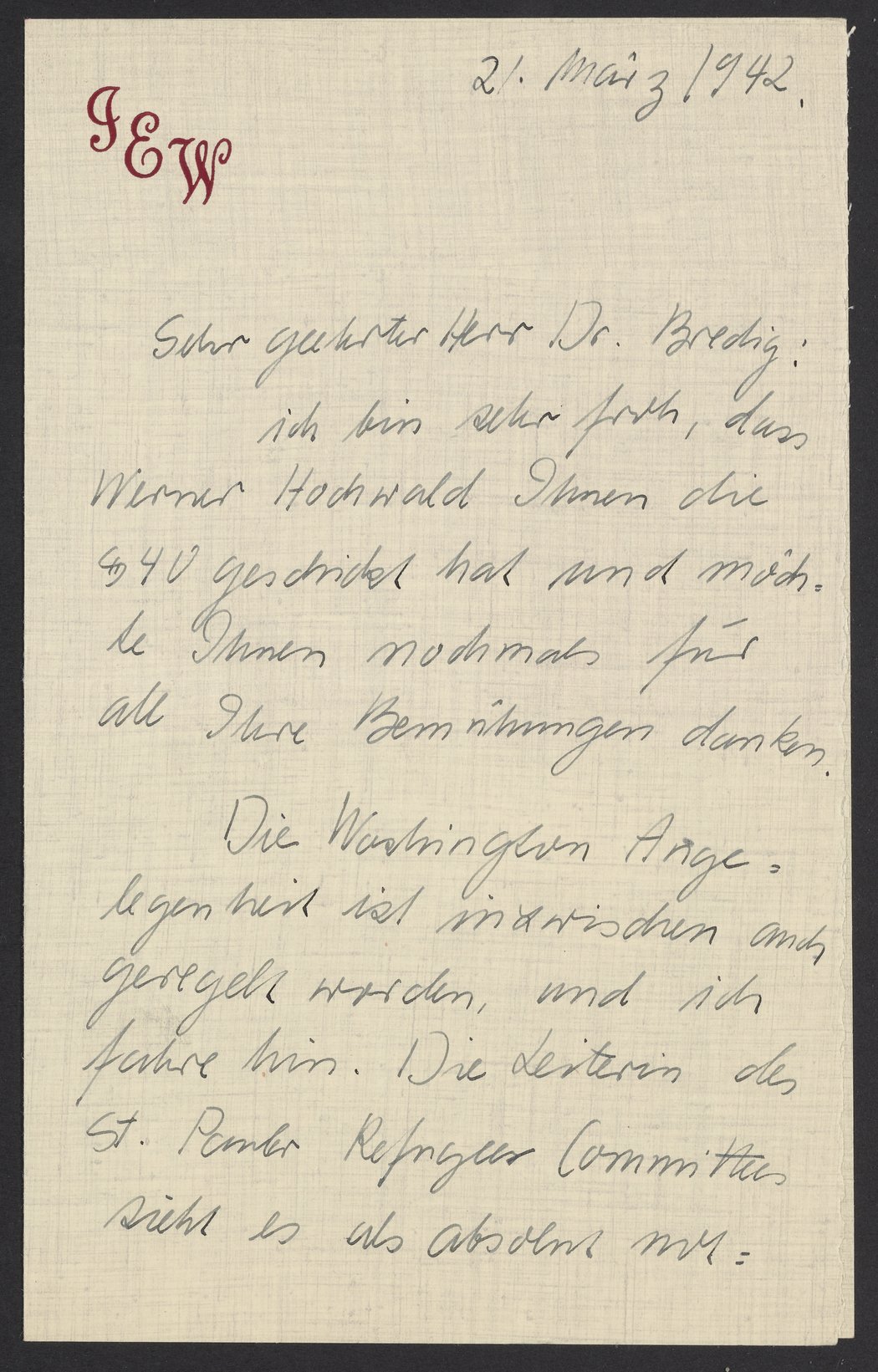

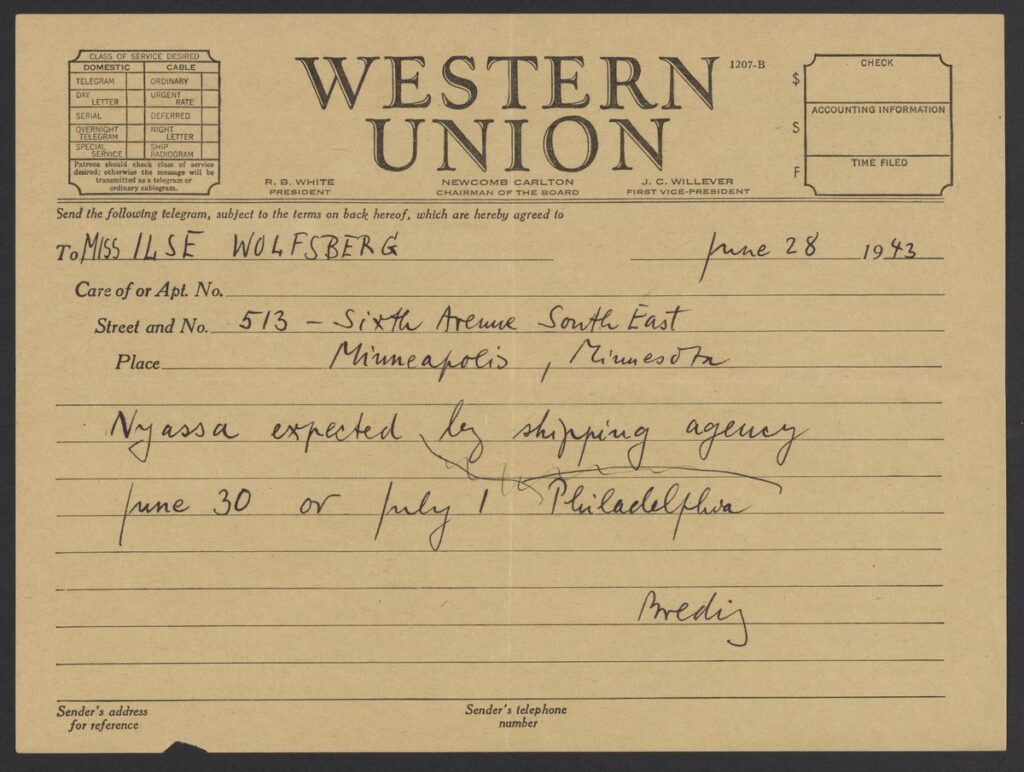

Bredig and Wolfsberg considered other ways to bring Hochwald to the United States. They considered getting Hochwald a Mexican or a Cuban visa. They also contemplated what a potential invasion of Spain during World War II would mean for his return. None of these ideas came to pass, but with the help of the personal references Bredig and Wolfsberg collected, Hochwald ultimately arrived in Philadelphia in late June/early July 1943, aboard the S.S. Nyassa.

Bredig and Hochwald remained in contact in the years after Hochwald’s immigration. In 1958, Hochwald finally repaid a debt of $100 that he owed to Bredig, joking that it was “unfortunately . . . no longer [worth] the same as it was in 1943.”

To me, Fritz Hochwald’s story is not only an emotional odyssey in the pursuit of freedom from tyrannical forces, but also shows scientists utilizing their non-scientific skills to aid them on their path to migration. Hochwald’s path to the United States shows the difficulty of obtaining American citizenship; recent political developments have made this process even more arduous. If nothing else, this acts as a powerful story of two individuals doing everything in their power to ensure their friend’s safety.

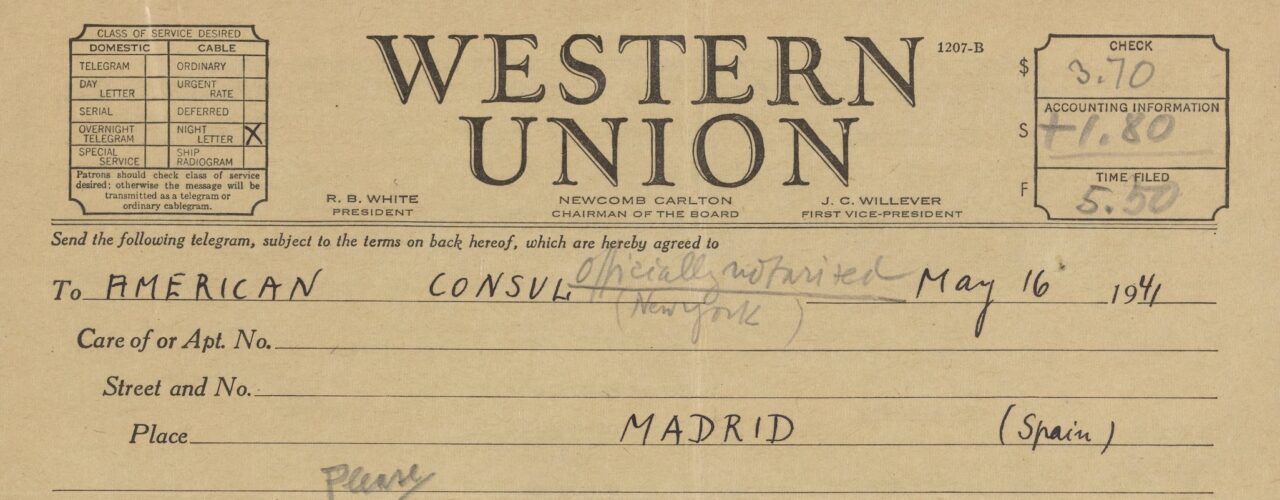

Featured image: In this telegram from Max Bredig to the American Consul in Madrid, Bredig praises both Fritz Hochwald’s character and his scientific bona fides.

The Institute’s museum education team partners with Philly Touch Tours to offer a more meaningful history of science experience.

Mapping Philadelphia’s industrial past with digital tools.

Memory, materials, and the history of science in the Eugene Garfield Papers.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.