The Pets We Love and the Pests That Love Them

A brief history of flea medicine.

A brief history of flea medicine.

This eye-catching can of Bee Brand Flea Killer, part of our Phil Allegretti Pesticide Collection, grabbed my attention while I was browsing our newly launched object collections database because it includes two of my favorite things: vintage graphics and animals. Then, as all my favorite collections items do, it prompted a series of chuckles and questions.

The instructions indicate that the product is for use on the rather strange grouping of “dogs, cats, foxes, and monkeys.” Were flea-ridden foxes and monkeys common in mid-century American homes? Are the active ingredients—1% rotenone and 2% other cube resins—still what we use for flea control today? When did the modern flea products that I use on the steady stream of stray and foster cats that pass through my home replace powders like Bee Brand, which have to be rubbed onto the animal and dusted onto their sleeping quarters? What does the evolution of flea treatment reveal about the status of companion and agricultural animals in our culture?

Though I’m aware that flea treatment has improved drastically in my lifetime (cue the traumatic memories of flea-bombing a beach rental in the early 1980s), I hadn’t given the history of flea medicine much thought. Until now.

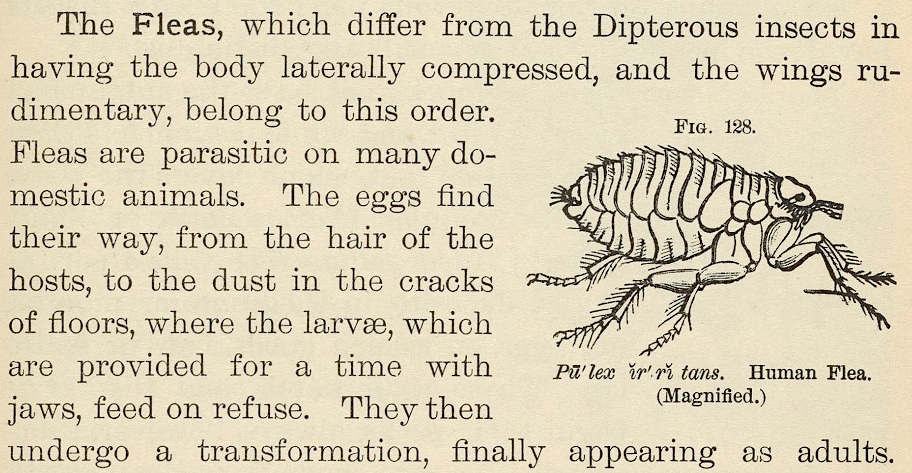

To understand the innovation of modern flea treatments, it’s important to understand the flea lifecycle. Female fleas need to eat blood from an animal or human host in order to mate and lay eggs on and around that host. After hatching from the egg, a flea enters a larval stage, during which it is mobile and feeds on blood and flea feces. After 5 to 20 days of feeding, the larva spins a cocoon and enters the pupal stage, during which it is impervious to insecticides and environmental conditions. It can remain in the pupal stage for up to a year until it detects a blood host, whereupon the adult flea emerges to eat a blood meal, mate, reproduce, and begin the cycle again.

Figure 128. Human Flea (Magnified) from Popular Zoology, 1887.

The flea treatments that entered the market in the 1990s were innovative because they effectively disrupted the flea life cycle. Earlier products only killed adult fleas, which meant that infestations recurred once eggs hatched and larvae developed into adults. Scientists had discovered in the 1970s that the class of compounds named benzoylphenylureas (BPUs) could kill insect larvae. Part of a broader class of insect growth regulators (IGRs), BPUs had the added benefit of low toxicity to vertebrates; in other words, they targeted fleas, not humans or larger animals such as cats and dogs. Like most insecticides used on animals, products using IGRs were initially developed for the agricultural pesticide market, but in the 1980s pharmaceutical companies such as Ciba-Geigy (now Novartis) surmised that a market might exist for flea treatments that were effective and safer for companion animals.

As noted by Pablo Junquera, then a scientist in the Animal Health division at Ciba-Geigy, developing products for use in non-livestock animals was also cheaper since there were fewer testing requirements for animals that wouldn’t be eaten by humans. For a fuller account of the development of cat and dog flea preventives in the 1980s and 1990s, see Junquera’s essay titled Lufenuron & Program: Episodes on Their Discovery, Development and Marketing.

In the early 1990s Ciba-Geigy introduced Program, the active ingredient of which was lufenuron, an IGR that works by inhibiting the development of larvae from fleas that have taken a blood meal from a lufenuron-dosed host. Competitors followed with other topical and oral treatments, the names of which are now familiar to dog and cat caretakers, including Frontline, Advantage, and Revolution. These used other newly developed ingredients such as fipronil, imidacloprid, and selamectin to inhibit flea growth, kill adult fleas, and in some cases, target other dog and cat pests such as heartworm and ticks. In all cases, the animal and its environment could be treated with one product. Moreover, these products were (and are) relatively inexpensive, convenient, easy to apply, and safer than their antecedents.

In contrast, prior to the 1990s, flea treatment was a messy, laborious, imprecise, expensive, and dangerous undertaking.

No. 481: Recipe for killing fleas from Recipes and Extracts on Alchemy, Medicine, Metal-working, Cosmetics, Veterinary Science, Agriculture, Wine-making, and Other Subjects, 1425-1450.

The earliest mention I found of flea treatment in our collections is early indeed. The Institute’s Othmer Library has a 15th-century Latin manuscript that contains, among other “recipes and extracts on alchemy, medicine, metal-working, cosmetics, veterinary science, agriculture, wine-making, and other subjects,” a plant-based recipe for killing fleas—Ad interficiendum pulices—that translates roughly as “[t]ake colocynth or wormwood or peach leaves or coriander herb boiled in water and sprinkle it through the house. They’ll all die.”

The inclusion of a recipe for killing fleas in this painstakingly created handwritten manuscript gives a sense of just how frustrating and unpleasant flea infestations have always been, and how desperate people have been for a solution.

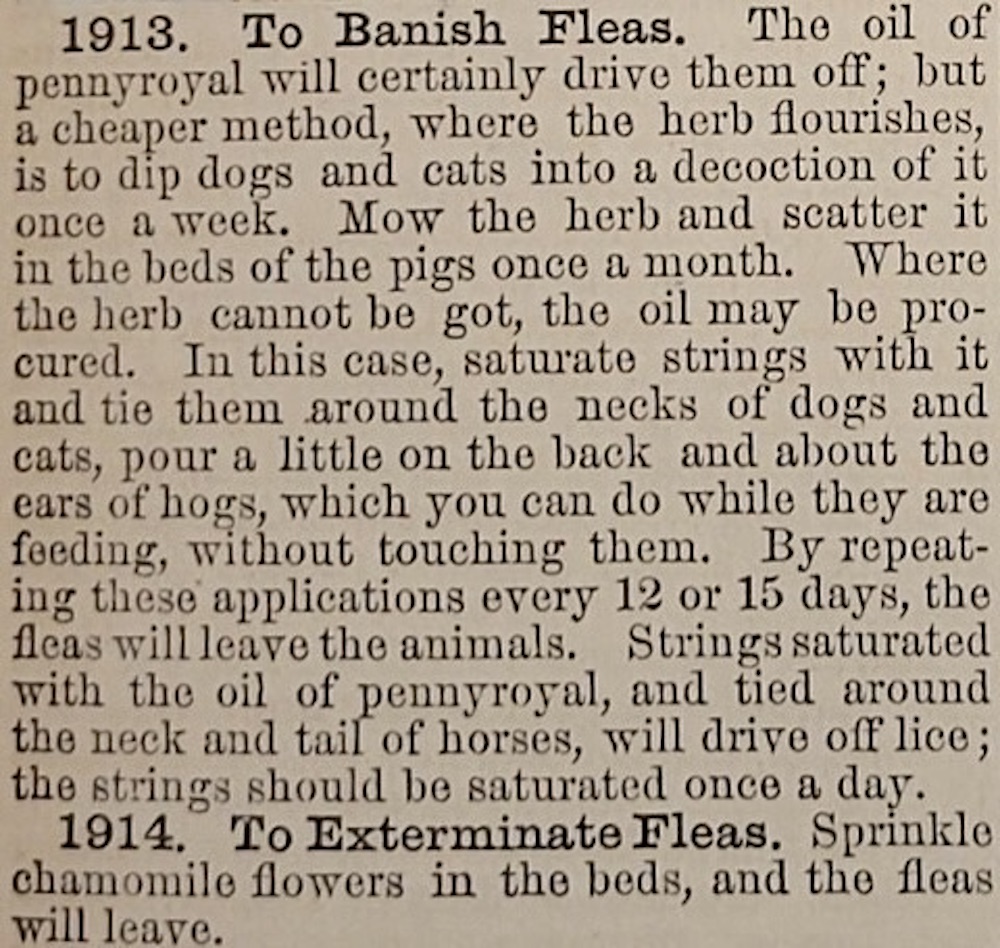

Indeed, three centuries later, flea control recipes continued to appear in works about home economics and domestic science, such as William Dick’s 1878 Encyclopedia of Practical Receipts and Processes.

One recipe recommends hanging strings soaked in pennyroyal oil around the necks of dogs and cats or dipping the animal in a pennyroyal “concoction” to banish fleas, while a second promises “extermination” via chamomile flowers sprinkled “in the beds.”

The public health consequences of flea infestations became clear in 1898 when Paul-Louis Simond (1858-1947) discovered that fleas transmitted the plague bacteria from infected rodents to humans. For much of the 20th century, flea control efforts focused on protecting humans and human dwellings, and livestock animals, as opposed to pets. Insofar as dogs and cats brought fleas into the home, of course, they were targeted for treatment, but products were not designed with their comfort and safety, nor the convenience of their caretakers, in mind. And unlike the products of the 1980s and 1990s, the active ingredients only killed adult fleas at the time of application with little residual effect. Thus any adults missed in the initial sweep, as well as eggs and larvae waiting to develop, went untouched.

Products for on-animal use were formulated as powders, like Bee Brand Flea Killer, or sprays, shampoos, or “dips” that had to be dusted, rubbed, sudsed, or otherwise applied to a probably reluctant animal, resulting in decreased effectiveness. Common ingredients in on-animal treatments were organic compounds like rotenone, derris powder, and pyrethrin, as well as pyrethroids (synthetic pyrethrins). These were tolerated to varying degrees by dogs and less well by cats, but toxicity was a persistent issue given methods of application that virtually ensured a pet would ingest more insecticide than recommended.

Consequently, flea infestations were ubiquitous and chronic, leading Arnold Mallis to opine in the 1945 first edition of his Handbook of Pest Control that “[s]ince dogs and cats are the usual carriers of fleas, they must be denied entrance into the home, or in any event must be thoroughly rid of fleas” before crossing the threshold. Options for the latter included bathing dogs (but not cats) in a 3% creosol solution or washing both in a kerosene emulsion with the salutary caution that “free kerosene will burn animals, and if any separates out, the mixture should be reheated.”

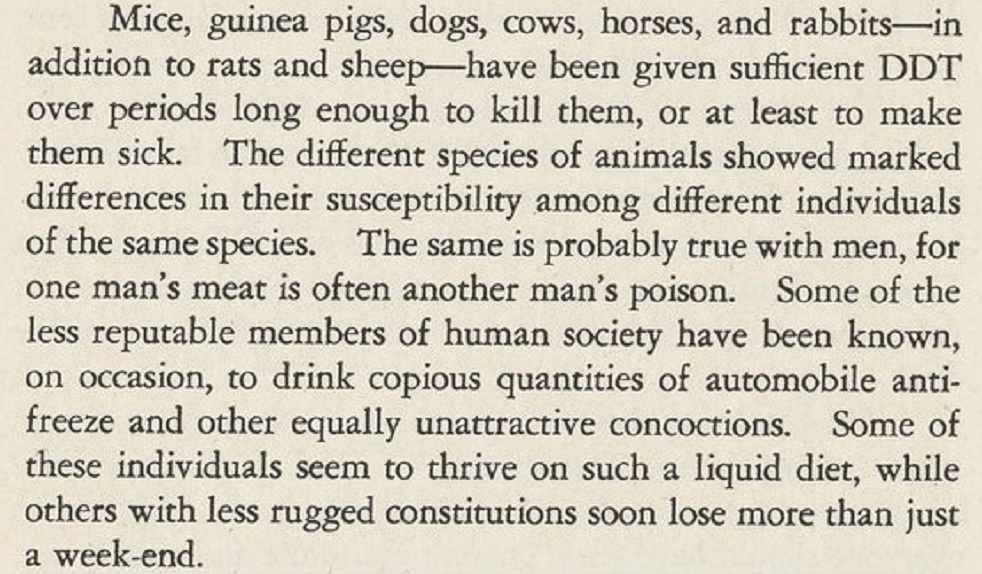

If that warning isn’t troubling enough, this first edition of Mallis’s Handbook reports a recent study in which fleas on dogs and cats were controlled by “dusting and then rubbing into the animals a powder containing 4 to 5 percent” of a new synthetic pesticide: DDT.

Hovering under this strange defense of DDT in DDT: Killer of Killers (1946) is the implication that an animal who ingests too much of the pesticide is like an alcoholic who drinks antifreeze.

By the third edition of Mallis’s Handbook in 1960, DDT had taken center stage as an active ingredient in flea-killing dusts for dogs, though the author warns “DDT dusts should not be used on cats since they are extremely sensitive to DDT, possibly because they lick themselves.” One wonders how many dogs didn’t get the memo and also ingested DDT after licking themselves.

Happily, at end of the 20th century, scientists started to develop new oral and topical treatments, the toxicity of which was targeted specifically at fleas. With their residual action and ability to kill both adult and larval fleas, these products made flea control safer, convenient, and accessible.

Today flea treatment for our dogs and cats is as easy as squeezing a tube of liquid onto the nape of a pet’s neck. As charming as I find our collections’ tin of Bee Brand Flea Killer, I’m grateful to live in the present when our cats and dogs are welcomed into our homes and, in many cases, our sofas and beds, and when we take their health and well-being into account alongside our own.

Featured image: Detail of can of Bee Brand Flea Killer, 1940s.

In pursuit of something memorable and meaningless.

How does a museum and library negotiate biography, civics, and the history of science?

Searching for the cats hiding in our collections.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.