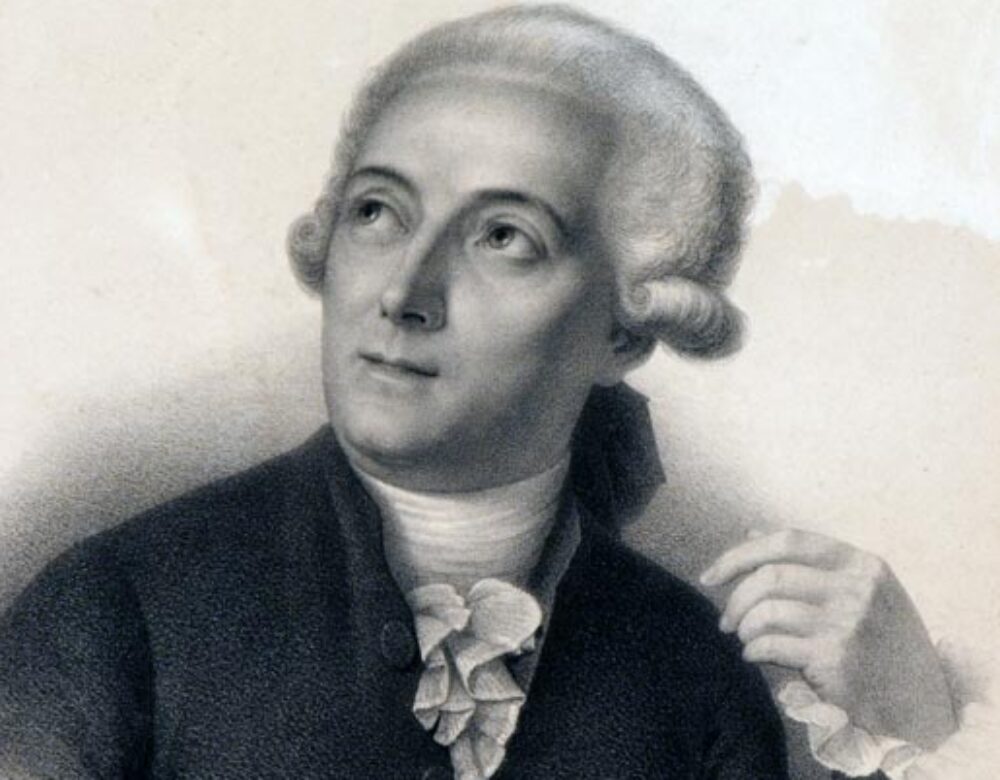

Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier

Considered the father of modern chemistry, Lavoisier promoted the Chemical Revolution, naming oxygen and helping systematize chemical nomenclature.

Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier, a meticulous experimenter, revolutionized chemistry. He established the law of conservation of mass, determined that combustion and respiration are caused by chemical reactions with what he named “oxygen,” and helped systematize chemical nomenclature, among many other accomplishments.

Scientist and Tax Collector

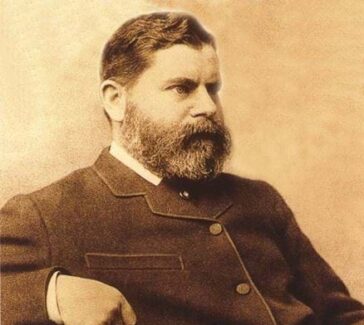

The son of a wealthy Parisian lawyer, Lavoisier (1743–1794) completed a law degree in accordance with family wishes. His real interest, however, was in science, which he pursued with passion while leading a full public life. On the basis of his earliest scientific work, mostly in geology, he was elected in 1768—at the early age of 25—to the Academy of Sciences, France’s most elite scientific society. In the same year he bought into the Ferme Générale, the private corporation that collected taxes for the Crown on a profit-and-loss basis.

A few years later he married the daughter of another tax farmer, Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze, who was not quite 14 at the time. Madame Lavoisier prepared herself to be her husband’s scientific collaborator by learning English to translate the work of British chemists like Joseph Priestley and by studying art and engraving to illustrate Antoine-Laurent’s scientific experiments.

Work with Gunpowder

In 1775 Lavoisier was appointed a commissioner of the Royal Gunpowder and Saltpeter Administration and took up residence in the Paris Arsenal. There he equipped a fine laboratory, which attracted young chemists from all over Europe to learn about the “Chemical Revolution” then in progress. He meanwhile succeeded in producing more and better gunpowder by increasing the supply and ensuring the purity of the constituents—saltpeter (potassium nitrate), sulfur, and charcoal—as well as by improving the methods of granulating the powder.

Promoting the Chemical Revolution

Characteristic of Lavoisier’s chemistry was his systematic determination of the weights of reagents and products involved in chemical reactions, including the gaseous components, and his underlying belief that matter—identified by weight—would be conserved through any reaction (the law of conservation of mass).

Among his contributions to chemistry associated with this method were the understanding of combustion and respiration as caused by chemical reactions with the part of the air (as discovered by Priestley) that he named “oxygen,” and his definitive proof by composition and decomposition that water is made up of oxygen and hydrogen.

His giving new names to substances—most of which are still used today—was an important means of forwarding the Chemical Revolution, because these terms expressed the theory behind them. In the case of oxygen, from the Greek meaning “acid-former,” Lavoisier expressed his theory that oxygen was the acidifying principle. He considered 33 substances as elements—by his definition, substances that chemical analyses had failed to break down into simpler entities.

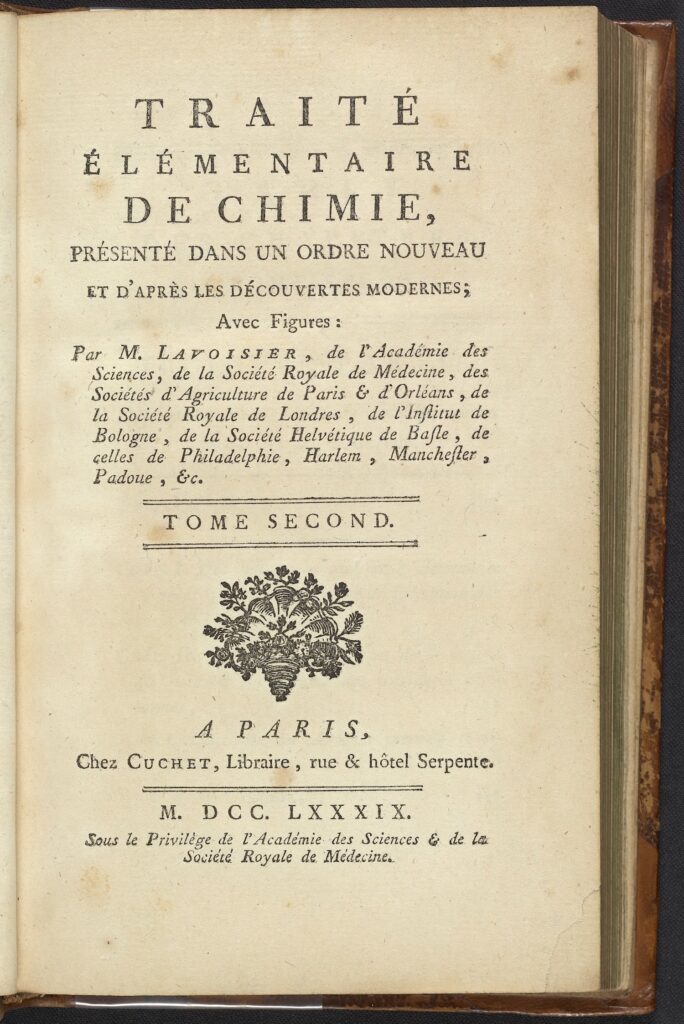

Ironically, considering his opposition to phlogiston (see Priestley), among these substances was caloric, the unweighable substance of heat, and possibly light, that caused other substances to expand when it was added to them. To propagate his ideas, in 1789 he published a textbook, Traité élémentaire de chimie, and began a journal, Annales de Chimie, which carried research reports about the new chemistry almost exclusively.

Politics and the Guillotine

A political and social liberal, Lavoisier took an active part in the events leading to the French Revolution, and in its early years he drew up plans and reports advocating many reforms, including the establishment of the metric system of weights and measures.

Despite his eminence and his services to science and France, he came under attack as a former farmer-general of taxes and was guillotined in 1794. A noted mathematician, Joseph-Louis Lagrange, remarked of this event, “It took them only an instant to cut off that head, and a hundred years may not produce another like it.”

You might also like

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

Revolutionary Instruments: Lavoisier’s Tools as Objets d’Art

In 1788 Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier and Jacques-Louis David were introduced during a sitting for the illustrious scientist’s portrait.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

The Trials of Lavoisier

Tracking the Reign of Terror through a revolutionary chemistry journal.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

The Science and Spectacle of the First Balloon Flights, 1783

The first balloons, both hot-air and hydrogen powered, drew spectacular crowds and set off a craze—balloonomania!