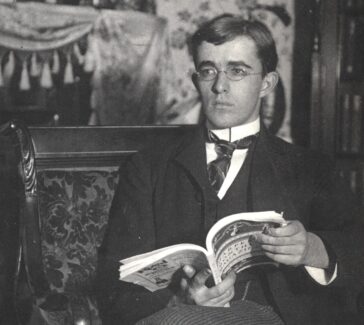

Edith Coleman

The Australian nature writer solved the orchid pollination mystery that puzzled Darwin.

Edith Coleman (1874–1951) published her first paper on Australian orchids at the age of 46. With no formal training, she became one of Australia’s most prolific and respected nature writers, achieving international fame for her work on the pollination of orchids by wasps through sexual mimicry.

LEARN MORE

Scientific writing usually refers to people by their surnames instead of their first names, but this can sometimes cause confusion. In many English-speaking countries, family names are patrilineal—children inherit their father’s names and women take their husband’s names when they marry. Such name changes can cause confusion when tracing women’s scientific work, especially if they collaborate with men. For example, some of Edith’s plant specimens are mistakenly attributed to her husband because they were recorded as being collected by Mrs. J. G. Coleman rather than E. Coleman.

Early Life

Edith was born in 1874 in a small town in Surrey in the southeast part of the United Kingdom. She was one of six children. Her father, Henry Harms, was a builder who loved nature and was a skilled beekeeper. He taught Edith how to look at plants and animals and how to ask questions about nature. Edith learned that even children in their own gardens could make new discoveries through patient observation. Her mother, Lottie, shared a love of English literature with the children.

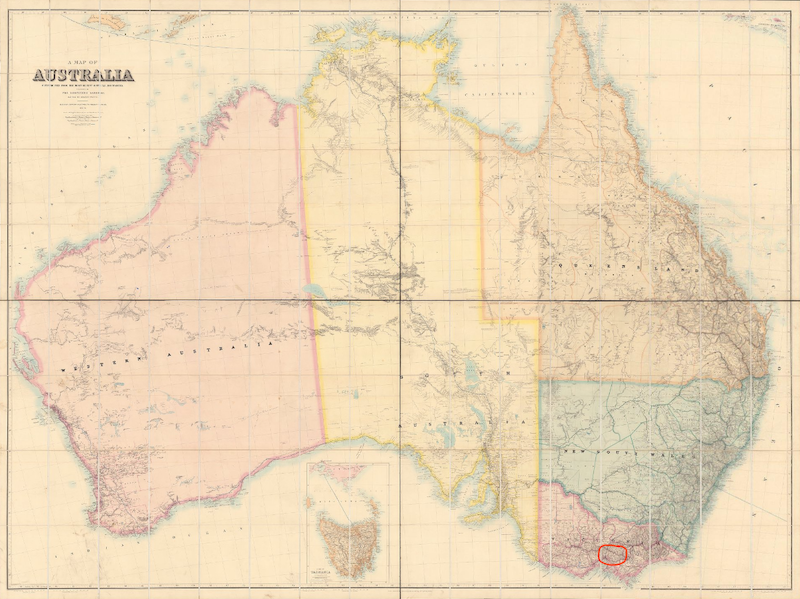

In 1887, when Edith was 13, the family emigrated to Melbourne, Australia, where the climate was better for the children’s health. At 15, Edith started training to become a teacher. At that time, teacher training was provided at the Worker’s Institute for Adult Education, where Frank Tate, a later director of education, strongly promoted the role of literature and outdoor nature study. This greatly influenced Edith’s later writing.

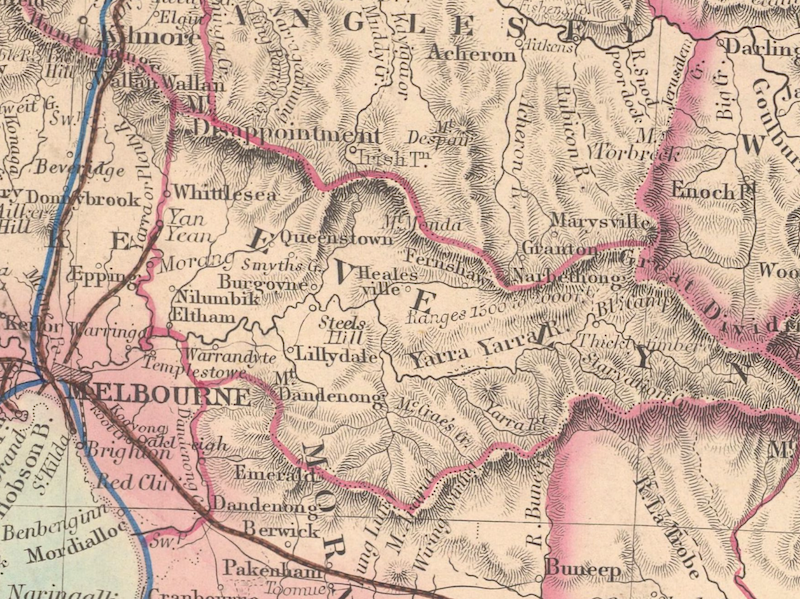

Edith was appointed to several tiny—and often poor—rural public schools, first as an assistant and later as head teacher. She then returned to teach in Melbourne, where she met her future husband, James (Jimmy) Coleman, in a bicycle shop. Jimmy became a successful businessman, importing motorbikes and cars and founding the Royal Automobile Club of Victoria. Jimmy and Edith married in 1898 and had two daughters, Dorothy and Gladys. They moved to the outskirts of Melbourne, then surrounded by native Australian woodlands.

Edith grew a rambling English-style cottage garden filled with flowers and scented herbs. She also explored the creeks, shrublands, and forests nearby for native Australian terrestrial orchids. When the suburbs spread around their home, the family purchased a cottage in the mountain forests in Healesville, where Edith spent even more time outdoors. She became known locally as an authority on wildflowers who happily shared her knowledge with others.

Publishing

When Edith was 46 and her daughters had finished school, she began writing and publishing articles on Australian orchids, which could still be found growing in the suburbs where she lived. Her first paper on “Forest Orchids” was illustrated by both Gladys and Dorothy, and published in a small local newsletter called The Gum Tree. In 1922 Edith joined the Field Naturalist’s Club of Victoria and presented her first scientific paper on autumn orchids, which was published in the club’s journal, the Victorian Naturalist. Over the next 29 years, Edith would publish around 12 papers a year in newspapers, popular magazines, and scientific journals. Many of her articles were on Australian terrestrial orchids and all shared her engaging writing style.

LEARN MORE

Field Naturalist clubs became popular in the 1800s and early 1900s. These clubs often arose out of scientific societies, but promoted outdoor research and did not restrict membership to trained scientists. Members included a broad mix of professionals and amateurs, men, women, and children. Can you find a community group near you with an interest in natural science? This might be a group interested in particular plants and animals (birds, fungi, insects, etc.) or a group interested in looking after a nature reserve. Do they have talks you can attend or activities to join?

Edith passed on her interests in natural history to her daughters, who both studied botany at Melbourne University. In addition to illustrating their mother’s articles, Gladys and Dorothy also illustrated and contributed to the work of other naturalists and scientists. Dorothy became a teacher and professional artist, while Gladys pursued a career as a botanist. Gladys also wrote a children’s wildlife column for the local Sydney newspaper, supporting herself and her husband, the anthropologist Donald Thomson.

Pseudocopulation and International Fame

In 1927 Edith and Dorothy noticed a wasp behaving strangely around the flowers of a small tongue orchid, Cryptostylis leptochila. Instead of entering the flower head-first to feed on nectar, this wasp was entering the flower backwards. While flowers generally produce nectar to encourage insects to visit and transport their pollen from one flower to another, orchids don’t always produce nectar. Other scientists—notably, Charles Darwin—had observed and puzzled over this behavior before.

Edith was able to confirm earlier suspicions with a series of careful experiments and observations. She discovered that all the wasps were male, and she demonstrated that smell, rather than visual mimicry, was the most important attractor.

She concealed orchids under a newspaper by a slightly open window and watched male wasps find their way to the plants. They showed little interest in orchids behind closed glass. The male wasps left carrying yellow packets of orchid pollen, demonstrating their important role in orchid pollination.

Edith corresponded widely with other scientists, both in Australia and internationally. She shared reprints of her Victorian Naturalist papers and specimens of Australian orchids. Academic researchers often sought her expertise on these species. Her paper on sexual mimicry in Australian orchids was reproduced in the Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society in 1928 by Edward Poulton, an expert in insect mimicry and a proponent of natural selection. Poulton didn’t ask Edith’s permission to do so, although he did ask local male scientists first whether her work was sound. Further publications appeared in the Proceedings of the Royal Entomological Society and the Journal of Botany.

In 1937 Professor Oakes Ames of the Harvard University Botanical Museum reviewed her work alongside other researchers in a paper on pseudocopulation, which cemented Edith’s international reputation. Flowers illustrated how natural selection might shape extraordinary shapes and forms to attract insects such as pollinators. Edith’s work helped explain why and how orchids attracted insects, even when they did not provide nectar as a reward—a behavior that had mystified even Darwin.

Diverse Achievements

Throughout her life, Edith suffered from debilitating bouts of Meniere’s disease, which caused dizziness, nausea, and hearing loss. Despite this, she published more than 350 pioneering papers on a surprisingly diverse range of Australian biology across plants, fungi, insects, reptiles, mammals, birds, and marine animals. She also published on less scientific topics, like gardening and herbs. In addition to naming several new species of orchids and their pollinators, she also pioneered studies of echidna hibernation, spider mating rituals, and budgerigar behavior. She published the only scientific studies of some Australian plants and animals. Her prolific output was testimony to a prodigious work ethic, which included trips to Western Australia and the inland desert, where she pressed and described plants, tracked animals, and wrote letters and papers for several hours each day.

Edith believed that everyone could study nature, even in a home or garden. She published in both scientific journals and women’s magazines and newspapers. She mentored and encouraged younger women naturalists like Jean Galbraith and Rica Erickson, and she engaged women and children in the natural sciences, contributing to a rising awareness of protecting and conserving nature.

LEARN MORE

During World War II, Edith often wrote about how women and children at home could contribute to the war effort. But she also thought there was another battle they were needed for: to protect and save Australian nature. In this opinion piece, she argues that women and mothers should play a vital role in conservation. Do you think she is right?

In 1949 Edith became the first woman to be awarded the Australian Natural History Medallion based on her distinguished record, the variety of her work, her “genius for accurate scientific observation,” and her “delightfully readable, descriptive phrases.” She completed her last paper two weeks before her death from cancer in 1951, when illness allowed her to “sit idly in the sunshine to watch the birds.”

Glossary of Terms

English–style cottage garden

The idea of cottage gardens arose in 19th-century England as an idealized mix of vegetables, flowers, fruit, and herbs for people living on small plots of land in the countryside. They rapidly became popular with more wealthy people as small informal gardens crowded with flowers, fruit, and herbs decorating an attractive cottage. They contrasted with highly formal and geometric European gardens.

Back >>

Pseudocopulation

Pseudocopulation refers to a pollination strategy where a plant mimics the appearance or chemical signature of an insect in order to entice the insects to mate with them. The plant attaches its own pollen to the insect, which then transfers it to other flowers of the same species.

Back >>

Further Reading

Clode, Danielle. 2018. The Wasp and the Orchid: The Remarkable Life of Australian Naturalist Edith Coleman, Picador.

Clode, Danielle. “Connecting Collections and Collecting Connections: Reconstructing the Life of Mrs. Edith Coleman,” Unlikely: Journal for the Creative Arts, v4. https://unlikely.net.au/issue-04/connecting-collections

McEvey, A. (1993). Coleman, Edith (1874–1951). In Australian Dictionary of Biography (Vol. 13), Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/coleman-edith-9784/text17291

Willis, J. H. (1950). “First Lady Recipient of Natural History Medallion – Mrs. Edith Coleman,” Victorian Naturalist, 67, 99.

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.

You might also like

STORIES BY TOPIC

Women Do Science, Too

Although women have often faced barriers to participating in science, science is definitely women’s work.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

Sesame Plots

Diaspora in twenty-one openings.

SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHIES

Helia Bravo-Hollis

The prolific botanist was the first woman to receive an advanced degree in biology in Mexico.