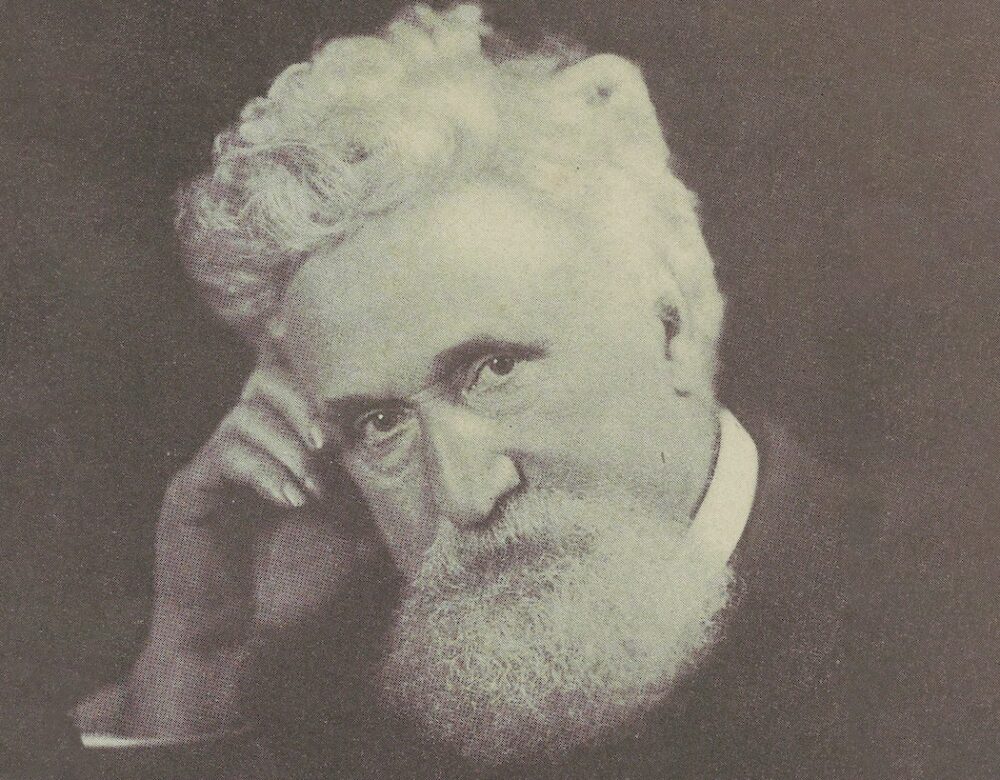

Hudson Maxim

Maxim was a chemist and inventor known for his work on weapons, particularly smokeless gunpowder.

Hudson Maxim (1853–1927) was an inventor, scientist, and writer who is best known for his work on the development of high explosives. Thomas Edison once called him “the most versatile man in America” because he had many talents and interests, including literature and chemistry. Through controversial popular writings, Maxim related poetry and weapons manufacture to higher-order laws of nature. He believed that the United States needed a strong military to protect itself and to prevent further conflicts around the world.

Early Life in Maine

Isaac Maxim was born on February 3, 1853, in the small town of Orneville, Maine; he changed his name to Hudson when he turned 18. He was one of eight children and his family was very poor. The Maxims moved around a lot when he was young because his father was always looking for better employment opportunities. Most of Maxim’s boyhood was spent on a farm in Guilford, Maine, where his parents let him run freely through the surrounding forests and lakes.

Maxim was curious about how things worked and took an interest in explosives from an early age. His father gave him a small shotgun for hunting when he was about 11 years old. “In all my love affairs,” he reportedly said, “that gun never has been outrivaled in its appeal to my affections.” An experimentalist at heart, one day he added an “extra charge of gunpowder” and blew a hole through the ceiling of his family’s kitchen. His mother, who he greatly admired, was incredibly upset. The experience made a lasting impression on him and may have motivated his later efforts to produce safer weapons.

Maxim could only afford to attend school part time, though he strongly desired an education. He began formal scientific study at the Wesleyan Seminary in Kents Hill, Maine, but he dropped out at age 18 to start working full time. As later quoted by a biographer, he once said, “I worked for two things—existence and an education.” He was very creative in his efforts to make money, which included the development and distribution of a patent medicine called “Maxim’s Lightening Cure,” and the incorporation of Knowles & Maxim, a small company that published books and manufactured new kinds of ink. Throughout these adventures, he continued to study chemistry on his own, hypothesizing in an 1889 article for Scientific American that atoms might be made of smaller parts. This idea was later proved to be true by J. J. Thomson.

Weapons Manufacture

At age 35, Hudson Maxim left New England to join his older brother, Hiram Stevens Maxim, in England. Hiram had by this time become famous for inventing the first fully automatic machine gun, which had brought him wealth and prestige in Europe. While in his brother’s employ, Hudson received a few grains of smokeless gun powder, which had been obtained by a coworker from a secret stockpile in Paris. The brothers immediately started testing the sample and claimed to have discovered its composition within hours. Just days later, the pair later reported, they had developed an improved version.

By 1888, Hiram’s Maxim-Nordenfelt Guns and Ammunition Company was booming. Hudson was sent back to the United States as a sales representative to make deals. Striking out on his own, he continued to tinker with the recipe for smokeless gunpowder, securing its first U.S. patent in 1889. When his contract with Hiram expired in 1891, he set up his own ammunition company, the Columbia Powder Manufacturing Company, to sell the smokeless gunpowder he had developed. The company did not last long: six years later, it was on the verge of bankruptcy. Hudson eventually sold its most important property to the E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Company in 1897, making a personal fortune in the process and rescuing his company from financial ruin.

Risky Research

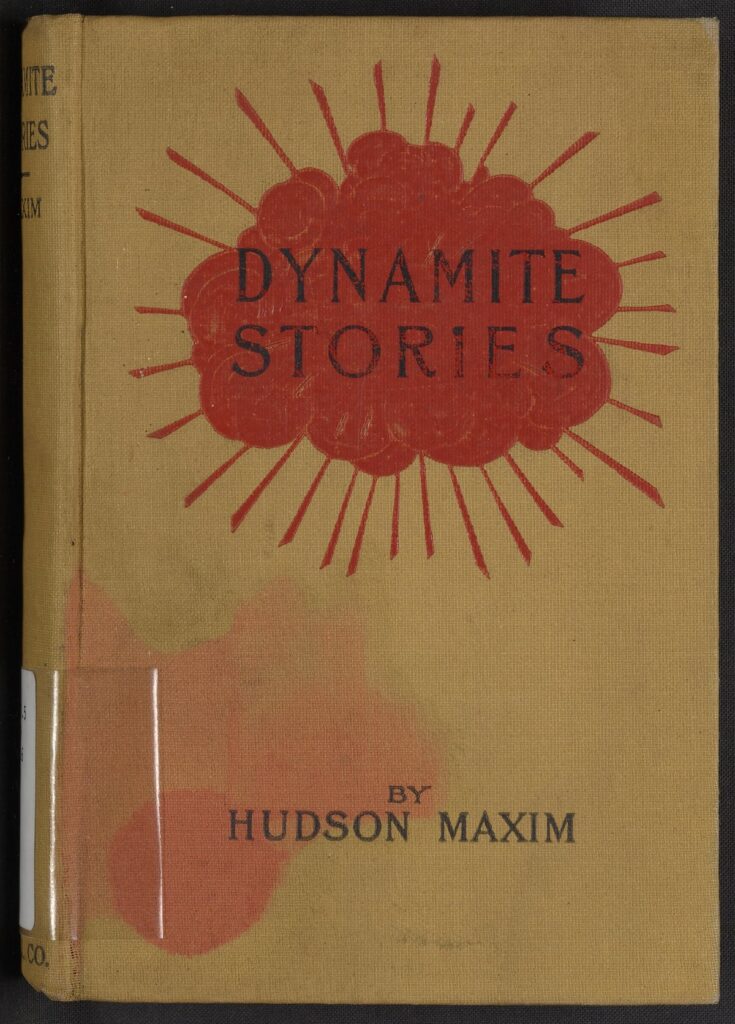

Hudson Maxim was well aware of the dangers that came with research on high explosives. He suffered a very serious accident in 1894 while working with mercury fulminate, Hg(CNO)₂, a very sensitive chemical that reacts easily to heat. He had been up all night with a toothache and was overly tired when he started to work with the compound the following day. A spark hit a “forgotten bit of fulminate” that he was holding onto, causing an explosion and destroying his left hand. Reflecting on this and other experiences in his 1916 book, Dynamite Stories, he advocated for “ceaseless vigilance” when it came to weapons handling.

LEARN MORE

Maxim defined high explosives, which he was particularly well known for, in opposition to other kinds of materials in the opening paragraphs of Dynamite Stories. Look at the first few pages of the book. Why do you think Maxim decided to write it? Do the facts he presents about explosives seem “interesting,” as he characterizes them, to you? Why do you think they interested him?

On the safe handling of explosive materials, Maxim argued that the greatest risk came from a lack of attention. He went on to compare personal safety and national security in many books and articles. Maxim’s work on high explosives sought to ensure domestic safety, even as his inventions proved ever more deadly to those on the receiving end.

He created a new explosive called Maximite, which was much more powerful than dynamite. Dynamite often exploded too soon and missed its target, whereas Maximite was designed to remain stable until it hit its target. Maxim justified his work on smokeless gunpowder, similarly, on the grounds that it would improve visibility—therefore safety—for the soldiers who fired it.

Maxim expanded these ideas about force and safety to the level of international relations in his controversial 1915 book, Defenseless America. In it, he argued against pacifist leaders and called for U.S. rearmament. The book expressed faith in U.S. businesses (including his own ventures) and stoked fears about foreign invasion. He helped pay for distribution of the book himself, having it placed alongside the Bible in nightstands at hotels across the country. Defenseless America was the basis of the silent film The Battle Cry of Peace; it was later said to have played a key role in the mobilization of U.S. forces during World War I.

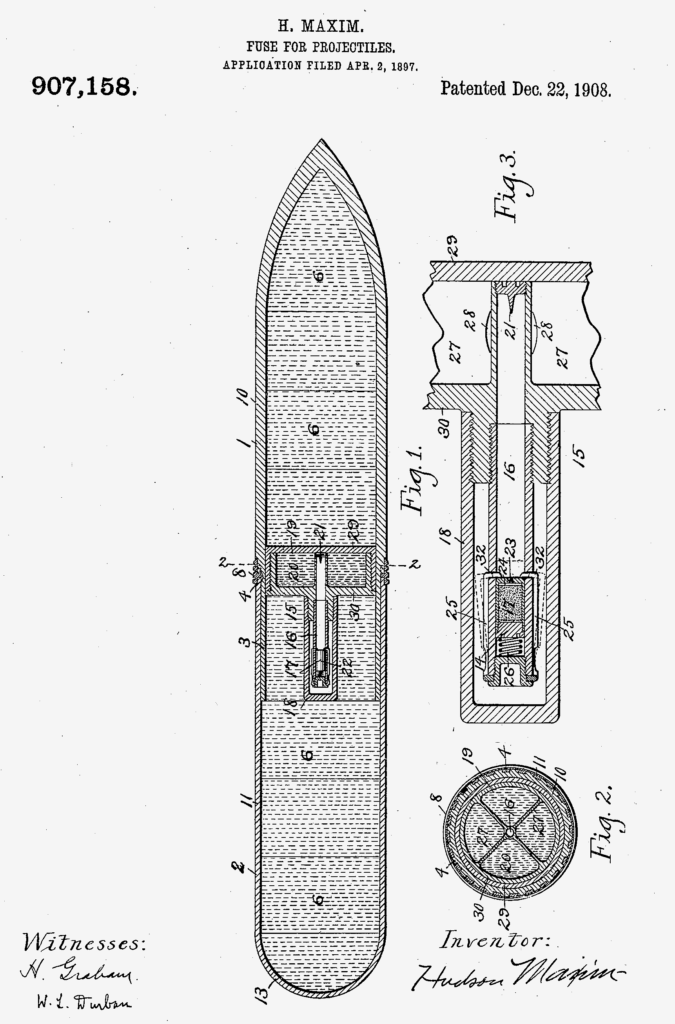

The explosives Maxim developed were not only used in combat, they were also applied to mining and construction. Blasting rock with explosives, for example, helped create tunnels, railways, and buildings. Maxim’s inventions improved worker safety and expedited the transformation of U.S. landscapes. As he wrote in his patent application for a new type of fuse for projectiles: “Provision is made to protect the charge of the shell against premature or accidental explosion of the detonating material.”

LEARN MORE

The decision to publish Hudson Maxim’s story, which is a decidedly violent one, was not easy. You can read more about some of the thinking behind this in a short essay titled “Collecting Lives and Live Collections.”

We have decided to include this biography because (a) Maxim had a large historical impact and (b) apparent contradictions in his life story open up a historical context that is different from our own.

Did Maxim reveal any perspectives that you find surprising? If so, how do they compare or contrast with your own?

“Intellectual and Moral Perfecting”

Maxim described his lifetime as an “age of mechanical and chemical engineering and invention, an age of material achievement” to biographer Clifton Johnson. He hoped it would pave the way for a new era in which people would have the freedom to focus on intellectual and moral goals. His thinking was deeply indebted to the writings of Herbert Spencer, the man who coined the phrase “survival of the fittest” and extended Charles Darwin’s ideas about biological evolution into the realm of human affairs. Through his research and writing on weapons of war, Maxim’s legacy represents the potential for an especially violent expression of what became known as Social Darwinism.

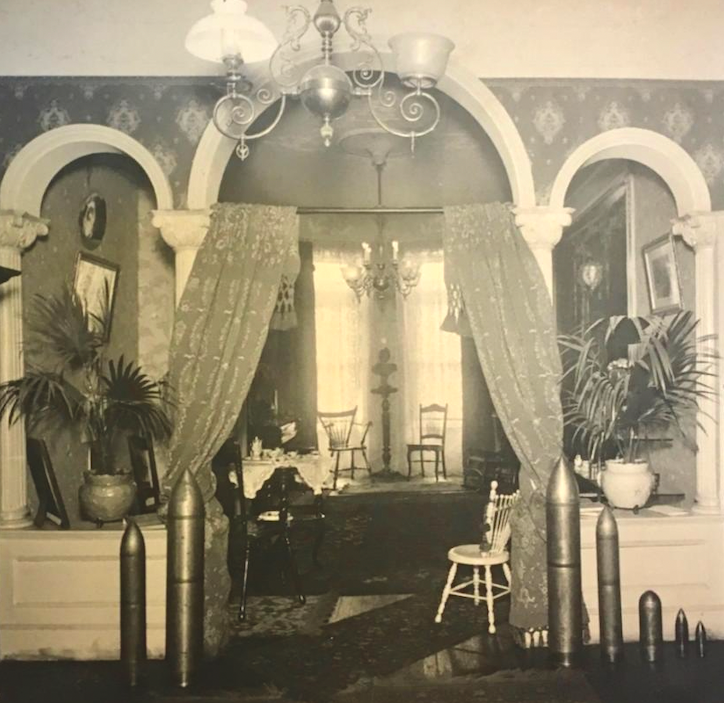

What kind of intellectual and moral projects did Maxim believe should follow his own lifetime of “material achievement?” He was a great defender of the literary pursuits that characterized his luxurious domestic life at Lake Hopatcong in New Jersey. At home, he set aside a lot of time for reading and recreation. He wrote extensively about the deep connections between chemistry and poetry, marveling at similarities between the heavy sounds of verse, storms, and explosives.

In The Science of Poetry and the Philosophy of Language, he explored historical connections between these interests (“poetry and gunpowder were born about the same time,” he wrote) and analyzed their formal similarities. He wanted to highlight the rules and patterns behind poetry so that audiences could understand the art form in a clear, logical way.

Maxim also fought for recreational opportunities on Lake Hopatcong, especially boating and fishing. He had moved to the area in the early 1900s when he went to work for the American Forcite Powder Company. During his free time away from the factory, he enjoyed spending time outdoors and on the water.

By 1904, he had purchased 600 acres around the lake, becoming the largest landowner in the area. When plans were made to turn the lake into a reservoir, he launched a successful campaign to preserve the lake as a site for recreation. He wrote a book in 1913 against the proposal and argued against it in newspapers and public meetings. His efforts succeeded in conserving the lake for recreational use, which earned him local monuments that still stand today.

Glossary of Terms

Social Darwinism

A set of theories, not supported by most scientists, that apply biological concepts to sociology, economics, and politics. The doctrine hinges on Darwin’s concept of natural selection, the idea that those traits that allow organisms to reach maturity and reproduce will be passed on, gradually accounting for the diversification of life on Earth.

Back to top

Conservation

An effort to protect natural resources for human use. This concept differs from preservation, which seeks to protect resources from human use.

Back to top

Further Reading

Buchanan, Brenda J. (Ed.). Gunpowder, Explosives, and the State: A Technological History. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2006.

Maxim, Hudson, and Johnson, Clifton. Hudson Maxim: Reminiscences and Comments, As Reported by Clifton Johnson. Doubleday, Page & Company, 1924.

Maxim, Hudson. The Game of War. McConnell printing Company, 1910.

“Science: Death of Maxim,” Time magazine, May 16, 1927.

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.

You might also like

SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHIES

Joseph John “J. J.” Thomson

In 1897 Thomson discovered the electron and then went on to propose a model for the structure of the atom.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

Boom Times

Follow the birth, life, and demise of the Hercules Powder Company, which once dominated the explosives industry in the United States.

SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHIES

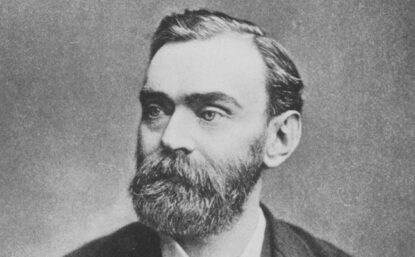

Alfred Nobel

The founder of the prestigious Nobel Prizes made his fortune with a big bang by inventing dynamite, a stabilized form of nitroglycerin.