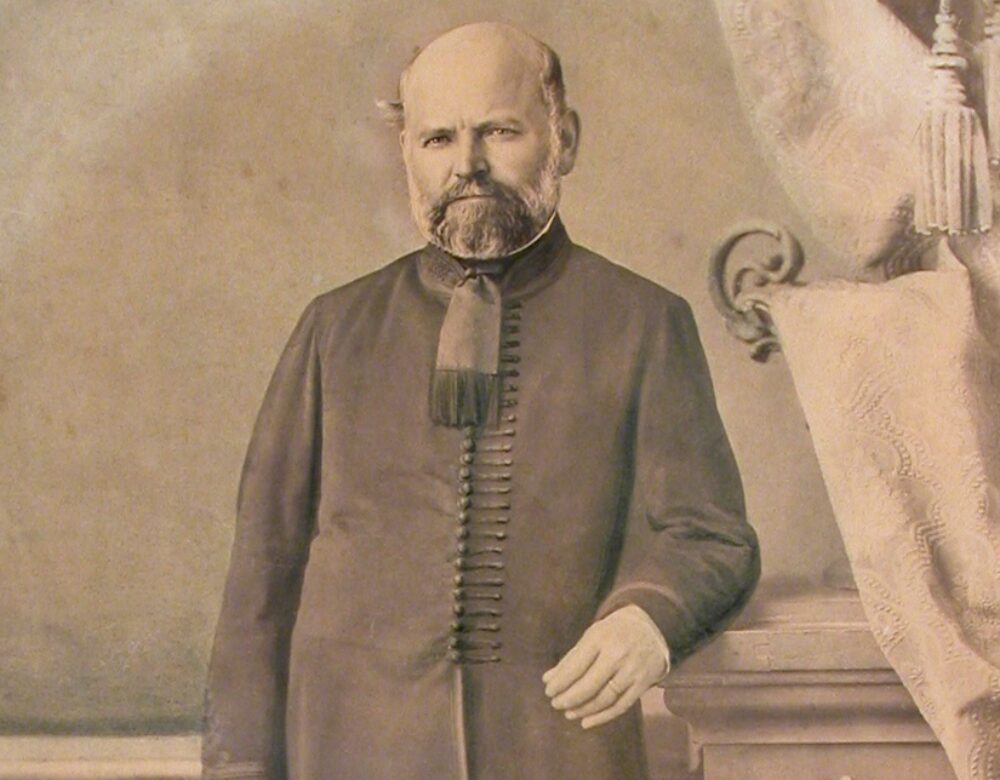

Ignaz Semmelweis

An early champion of women’s health and antiseptic medicine.

In 1847, Ignaz Semmelweis (1818–1865) identified the cause of childbed fever, an illness that claimed the lives of many new mothers. He realized that physicians were spreading infections and that handwashing could prevent the spread, making him a pioneer of antiseptic medical procedures. This significant discovery was not recognized in his lifetime: colleagues in the medical community refused to believe that they were causing patients to die through the transmission of infectious material. Nevertheless, Semmelweis was steadfast in his belief that handwashing, now considered basic hygiene, could reform obstetric healthcare. As he wrote in an open letter to the medical community, he was not interested in academic recognition. Instead, his goal was to have a practical impact “so that…the child can keep their mother.”

Pathway to Obstetrics

Semmelweis was born to a wealthy grocer’s family in Tabán (now part of Budapest), Hungary in 1818. He was an excellent but unfocused student. His father, József, encouraged him to become a military judge, thinking that a law degree would offer a stable career in uncertain times. Semmelweis tried to follow his father’s wishes and began studying law at the University of Vienna in 1837, but soon felt called to medicine, earning his degree in 1844. Though he hoped to work as an internist under his professor, Joseph Škoda, the position went to another candidate. Semmelweis instead joined the obstetrics department at the Vienna General Hospital. There, he completed advanced training in surgery and obstetric medicine.

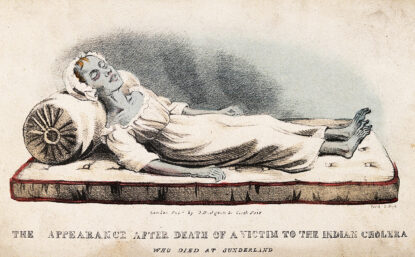

In the 1800s, childbirth was quite dangerous. Women suffered from illnesses after delivery, which were often fatal. Today we know that such infections typically occur when the female reproductive tract becomes contaminated following childbirth or miscarriage. But in the mid-1800s, the cause of childbed fever (also known as puerperal fever) was unknown. The most widely accepted theory was that maternal deaths were caused by miasma—bad air. Through experiences at the Vienna General Hospital, Semmelweis began to doubt this explanation.

“Savior of Mothers”

Settling in to his new specialty, Semmelweis began working closely with a pathologist named Carl von Rokitansky. As part of his practice, von Rokitansky performed autopsies on women who had died in childbirth. Together, the two doctors tried to understand why so many women across Europe were dying of childbed fever.

Semmelweis noticed differences between the two obstetrics wards at the Vienna General Hospital: the physician-run ward had a mortality rate three times higher than that of the midwives’ ward. No cases were reported outside the hospital—women who gave birth at home were unaffected.

He struggled to understand why midwife-assisted hospital births were safer than deliveries at the hands of physicians. The pregnant women were from similar social backgrounds and both groups were delivering in the hospital, so it seemed unlikely that bad air was the cause. He began to think, instead, that childbed fever was the consequence of a specific, preventable cause.

In 1847, Semmelweis had an important realization. His colleague, Jakob Kolletschka, died tragically that year after his hand was cut with a scalpel during an autopsy. Kolletschka quickly fell ill with sympotms affecting his abdomen, lungs, and brain. These symptoms closely resembled those of childbed fever. Semmelweis immediately thought there must be a connection between the two cases because the pathological findings were identical. He concluded that the source of childbed fever was cadaveric contamination.

Experimenting on himself, Semmelweis first tried washing his hands with soap, water, and a nail brush after autopsies. Seeking something stronger, he later tried chlorinated water. Ultimately, however, chlorinated lime—which was also used to whiten paper, clean stables, and sterilize drinking water—proved to be a cheaper solution. He found that chlorinated lime effectively eliminated the odor and with it, the “poison.”

Within months of Kolletschka’s death, Semmelweis implemented a new policy in his ward at the hospital in Vienna: all doctors and medical students were required to disinfect their hands with chlorinated lime before examining pregnant women. This marked the birth of antiseptic procedures at the Vienna General Hospital. Though physicians might have complained that the chemicals burned their hands, the mortality rate in Semmelweis’ ward decreased dramatically—from 18.27% to 1.27%—in 1848.

LEARN MORE

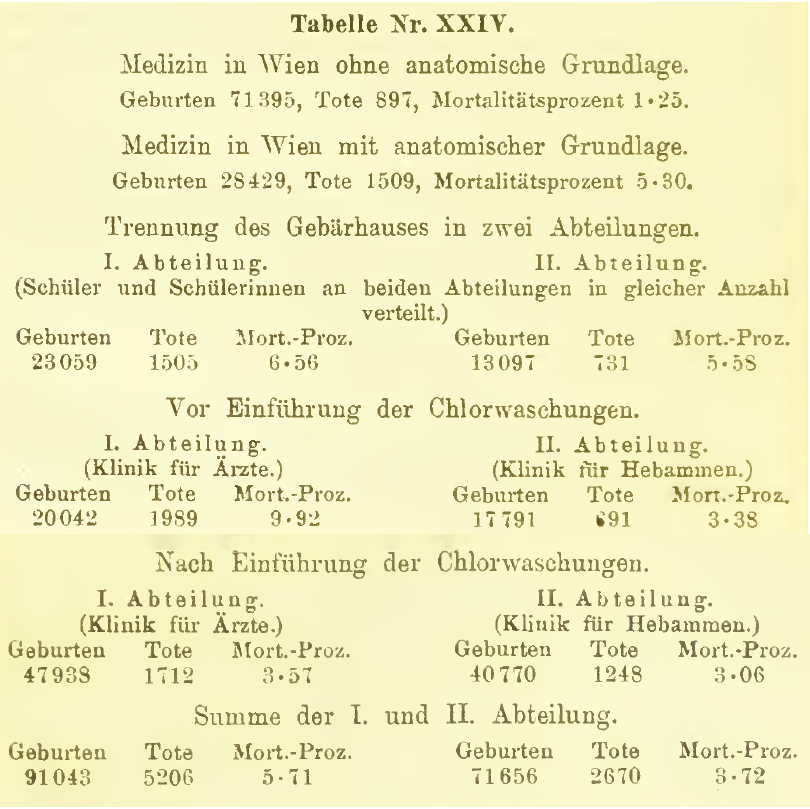

Medicine became statistical during the 1800s. The analysis of patient statistics, along with pathological research, helped physicians better understand patterns of disease.

Semmelweis included tables in his major book on childbed fever comparing birth and death rates in hospitals across Europe and over time. His tables also compared statistics between the physicians’ ward of the Vienna General Hospital (which, after a series of decrees in 1840, was populated exclusively by male trainees) and the midwives’ ward (which was reserved specifically for women trainees). The table shown at right demonstrates the difference in mortality rates across the two wards after mandatory handwashing was introduced.

View a transcription of the table by the author of this biography.

Struggle to Save Lives

The introduction of mandatory handwashing met with resistance. Semmelweis’s superior, Johann Klein, for example, could not understand the significance of handwashing for a fever he continued to think was caused by bad air. However, some physicians who supported Semmelweis began writing letters to professors all over Europe to share news of his findings, bringing international attention to the debate.

Semmelweis found some allies. Karl Haller, deputy director of the Vienna General Hospital, helped disseminate word of the “cadaverous poison.” At Haller’s suggestion, the Austrian Medical Association invited Semmelweis to present his research. But a majority of physicians remained critical of his findings in the years before Louis Pasteur confirmed the germ theory of disease.

As his ideas became more widely known through letters and publications in medical journals, Semmelweis’s professional relationships began to deteriorate. Klein, in particular, treated him poorly. On March 20, 1849, Klein dismissed Semmelweis from his position at the Vienna General Hospital.

After he was fired, he returned to Hungary and began working at Szent Rókus Hospital in Pest (today, part of Budapest). It was there that he later published his major work on the subject, Die Ätiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers [The Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever] (1861).

LEARN MORE

Klein’s opposition also had a political undertone: during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, which targeted the ruling Habsburgs, the conservative Austrian Kelin grew hostile toward Semmelweis, who supported the revolutionaries. The Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence (1848–1849) was part of a wave of European revolutions. The Hungarians demanded national independence from the Austrian Empire. The revolution turned into an armed struggle, which was eventually crushed with the help of Russian troops. Decades of turmoil eveutally were resolved with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, which established the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary.

Semmelweis sent copies of his book to prominent obstetricians and scientific institutions across Europe. But many physicians continued to dismiss the effectiveness of handwashing with chlorinated lime. He had hoped his book would fundamentally change the understanding of childbed fever, and this widespread rejection deeply affected him.

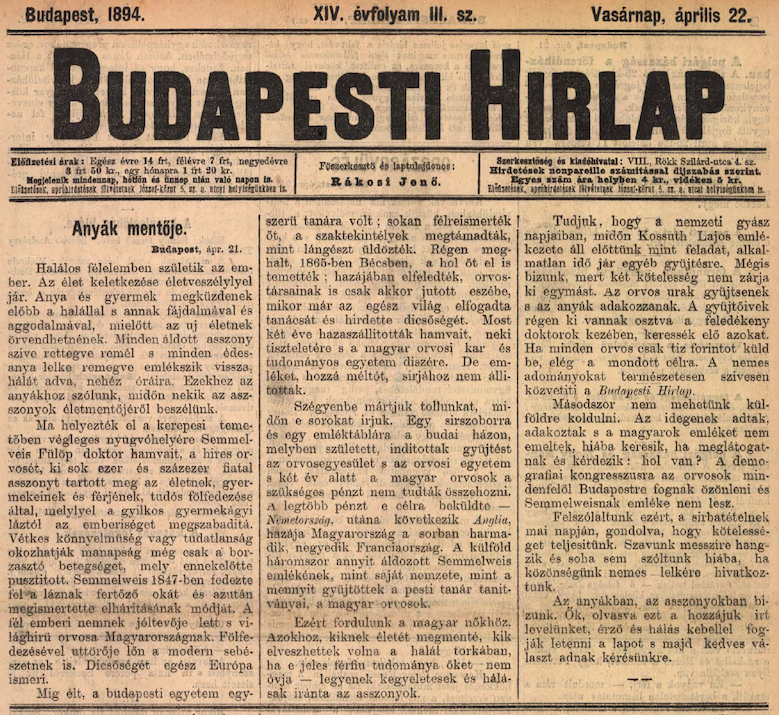

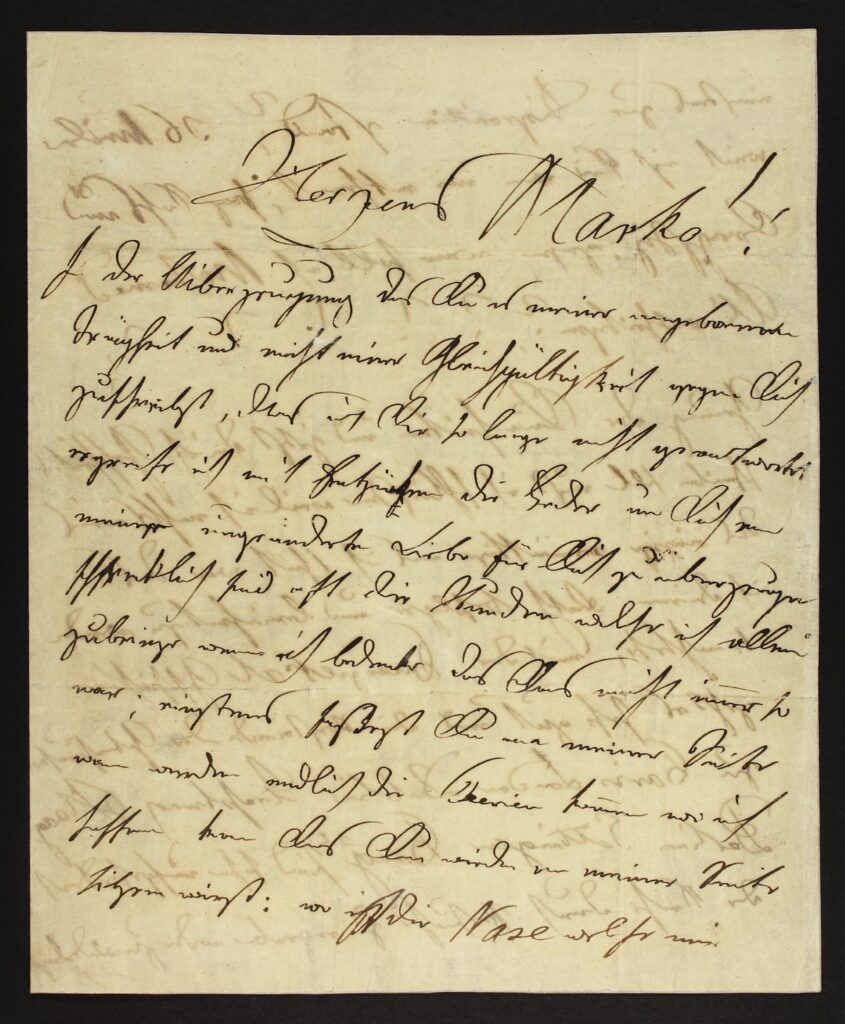

In his growing frustration, Semmelweis wrote open letters addressed to the international medical community. In these letters, he expressed his anger and disappointment at the “massacre” for which he believed his colleagues were responsible:

Semmelweis was fighting not for recognition, but for the lives of new mothers. His open letters challenged the European medical establishment. Their tone—emotional, furious, and accusatory—reflected his beliefs about the gravity of the situation.

Semmelweis remained unwavering in his convictions, but the struggle to have his ideas accepted took a severe toll on his mental health. Over time, his psychological state deteriorated. Eventually, he was committed to a mental institution in Oberdöbling, outside Vienna, where he died in 1865. It was only after his death that his findings were accepted throughout the medical establishment.

Glossary of Terms

Internal medicine

A general medical practice focused on the causes of symptoms and syndromes; practitioners typically practice in hospitals.

Back to top

Pathology

The scientific study and diagnosis of disease.

Back to top

Cadaveric

Relating to a dead body.

Back to top

Chlorinated lime

Chlorinated lime or calcium hypochlorite is a white powder used for bleaching or disinfecting.

Back to top

Further Reading

Obenchain, Theodore G. (2016) Genius Belabored: Childbed Fever and the Tragic Life of Ignaz Semmelweis. University of Alabama Press.

Kapronczay, Károly (2015) Semmelweis. Budapest: Magyar Tudománytörténeti Intézet.

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.

You might also like

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

The Nurse Who Introduced Gloves to the Operating Room

Caroline Hampton and the forgotten origins of the first personal protective equipment.

DISTILLATIONS PODCAST

The Mothers of Gynecology

Why are Black women in America three times more likely to die during childbirth than White ones?

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

John Snow Hunts the Blue Death

In showing that cholera spreads through tainted water, an English doctor helped lay epidemiology’s foundations.