Julius Richard Petri

A physician who studied bacteria, Petri’s name became associated with small covered dishes that are essential to laboratory research in the life sciences.

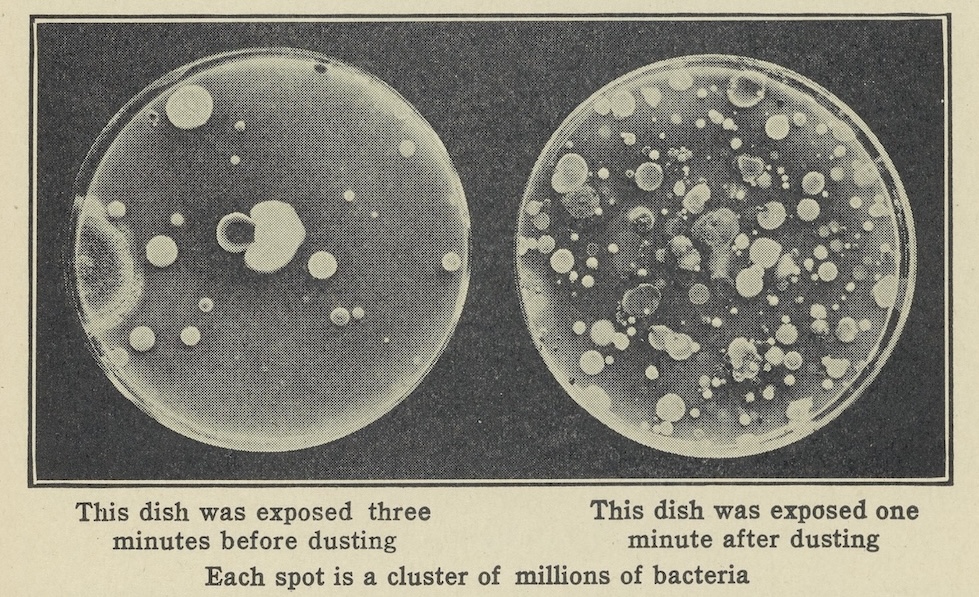

Sometimes a new method is just as significant as a new truth about nature. Our current understanding of bacteria developed hand-in-hand with the development of laboratory tools and techniques in the late 1800s. These helped researchers isolate and identify distinct species of bacteria. The Petri dish was crucial to the period that became known as the “Golden Age of Microbiology”—from the mid 1800s to early 1900s—because it protected bacterial cultures from contamination with a tight-fitting lid. It has been an essential part of laboratory research ever since.

Education and Early Career

Julius Richard Petri (1852–1921) was born in Barmen (present-day Wuppertal), Germany to a highly educated family. His grandfather studied ancient languages and his father was a professor at a gymnasium in Berlin. Coming of age at the dawn of the German Empire (1871–1918), he studied to become a military physician at the Kaiser-Wilhelms Akademie for Military Medical Education (also known as the Pépinière) between 1871 and 1875. This highly competitive school provided a medical education alongside training in military skills, and it was free to those middle- and upper-class students who were selected to attend. In 1876, Petri graduated with a thesis on “The Chemistry of Protein Urine Tests”[“Versuche zur Chemie des Eiweissharns”] following a one-year residency at the Charité hospital in Berlin. He then went to work as a military physician.

Typically, graduates of the Pépinière would have spent eight years in military service upon graduation. Petri left just shy of this mark to join physician Hermann Brehmer in Görbersdorf (present-day Sokołowsko, Poland). Brehmer had established the world’s first sanatorium for patients with tuberculosis, an infectious disease that primarily affects the lungs. Treatment at Brehmer’s sanatorium was holistic and quite expensive: it included hydrotherapy, a specific dietary regimen, and plenty of fresh air. A more targeted cure for tuberculosis was not available at the time, though this would become one of Petri’s major research interests.

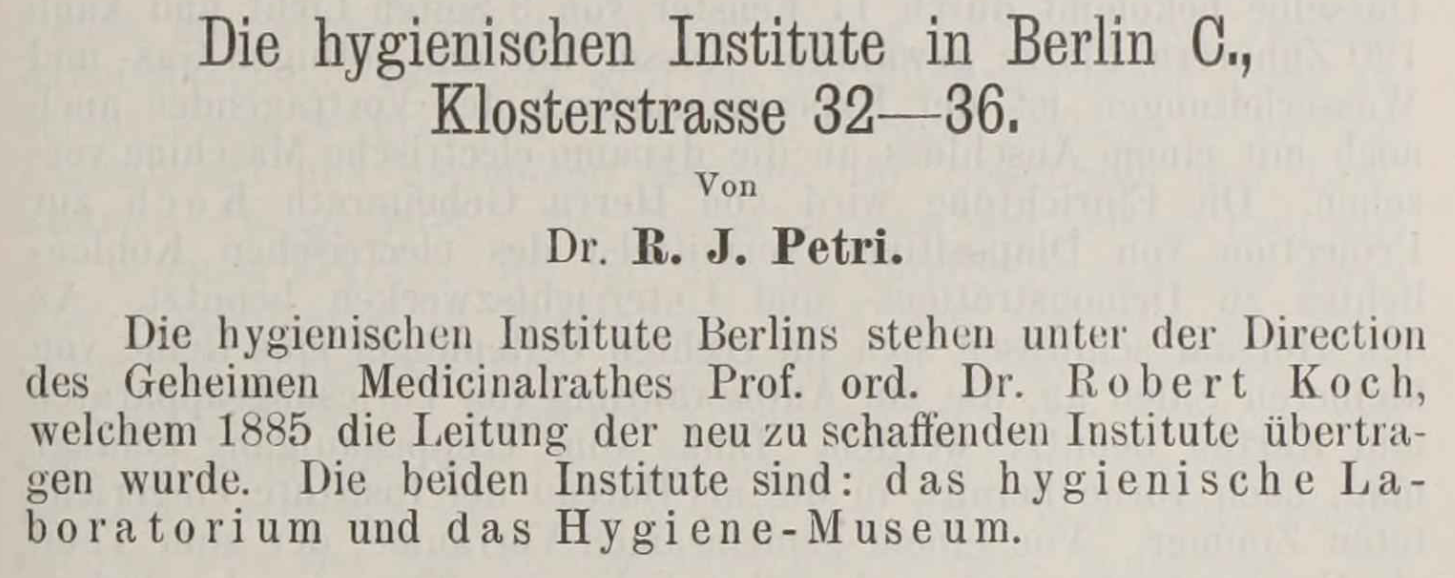

In 1886 Petri moved back to Berlin, where he became a Privy Councilor—a government advisor—in the Imperial Health Office. In this role, he went to work in the newly established Hygiene Institute of Robert Koch, taking on curatorial responsibilities in the Hygiene Museum and conducting research in Koch’s bacteriology laboratory.

The Hygiene Museum grew out of a temporary exhibition that had attracted a huge amount of public interest. When the Ministry of Culture made the exhibition permanent in 1885, placing it under Koch’s direction, it ignited a controversy with other established medical authorities. The prominent pathologist and liberal politician Rudolf Virchow, for one, objected loudly to the arrangement, arguing that hygiene was not an exact science.

In an 1887 overview of the Institute, Petri did describe a wide range of activities and collections that differ from the way people might think about science today. The exhibits Petri oversaw included materials on maritime and firefighting rescue services, workers’ housing, and dust exhaust doors; information on bathing establishments, “clothing hygiene,” and gymnastics; observation stations for monitoring groundwater and soil; as well as a library for further self-directed study. Petri celebrated the cutting-edge nature of these exhibits just as he did the expensive new equipment in Koch’s well-lit teaching laboratory. The humble but transformative Petri dish came out of the self-consciously modern research and teaching facilities at Koch’s Hygiene Institute in the Empire’s capital city.

LEARN MORE

Does the range of exhibitions and laboratory equipment at the Hygiene Institute surprise you? Why or why not? What do you think Koch and Petri meant by the term “hygiene?” How does this term compare to the way that we talk about “science” today?

Contribution to “Koch’s Plating Technique”

Petri joined Koch’s laboratory at a time of very active research on microorganisms. This period witnessed intense interest in fermentation, for instance, disproved the idea that microbes grow by “spontaneous generation,” and established the “germ theory of disease.” Such sweeping theoretical developments depended on a series of incremental methodological improvements.

One of these was the introduction of agar, a medium for growing bacteria, by Fanny Angelina Hesse. Because agar was more stable than the liquid and gelatine media that had been tried before, it allowed researchers to make more precise observations. It became part of “Koch’s plating technique” (also called the “culture plate method”), in which bacteria were grown on a solid medium in a shallow glass dish under a cover. Koch’s name became associated with this technique after he spoke about it at the 1881 International Medical Congress in London, even though other researchers were using similar methods at the time.

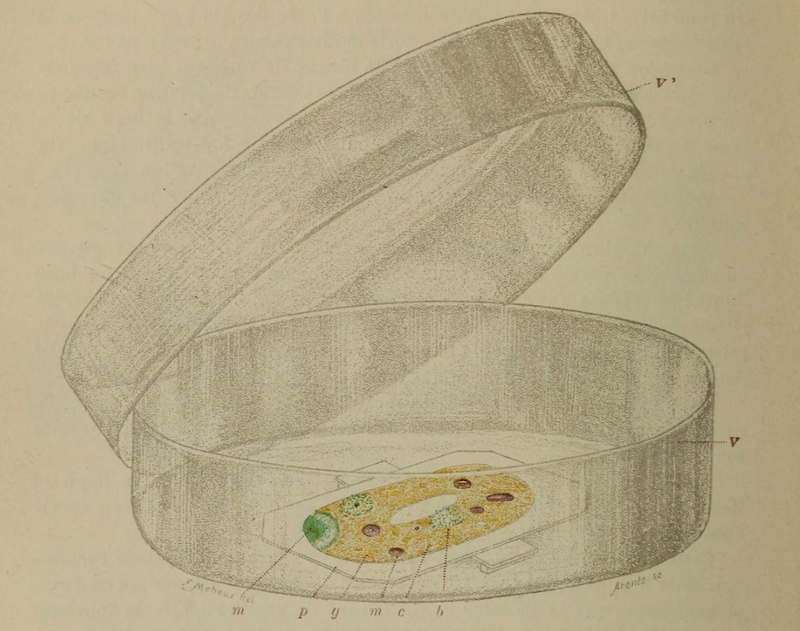

To study the tuberculosis bacterium (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) and other microbes, Koch and his assistants placed streaks of bacteria on a solid culturing medium atop a microscope slide that was placed in a glass chamber with a lid. The lid, in this case, helped maintain the humidity the culture needed to grow. It also kept other microorganisms from entering. But whenever the time came to handle or observe these cultures under the microscope, the moist chamber had to be opened to remove the slide. This introduced the risk that microbes from the surrounding environment could infiltrate the culture, growing in an uncontrolled way and misleading the observer.

Petri’s solution to this problem was to fix a snug glass lid over the top of each dish—one that would stay put being small and flat enough to fit directly under the microscope. In this way, dishes could be handled and observed without opening. Petri published a modest note on this approach, “A Small Modification of the Plating Technique of Koch” [“Eine kleine Modification des Koch’schen Plattenverfahrens”], as part of his 1887 report on the activities of the Hygiene Institute. The publication helped cement the association of his name with both Koch’s prestigious Institute and the dish, which is why we talk about “Petri dishes” today.

Later Career

Petri worked with the Imperial Health Office until 1900, when he returned to Görbersdorf as the director of the sanatorium where he had previously been an assistant. He published numerous articles, monographs, and dictionary entries over the course of his career on everything from fundamental research methods to hygiene, and the control of infectious diseases.

In his 1896 book, The Microscope from Its Beginnings Up to the Present, for All Friends of This Instrument [Das Mikroskop, von seinen Anfängen bis zur jetzigen Vervolkommung für alle Freunde dieses Instruments], Petri made his main interests clear. He wrote:

Petri was fascinated by the microscope and the world that it helped him to see. His “small modification” of Koch’s plating technique was made to fit the microscopes of his day, on which the scientific authority of his field depended.

In our own time, millions of Petri dishes are used every day in laboratories and field sites around the world. They maintain humidity, prevent contamination, and can be easily transported. The design of the Petri dish has remained fairly consistent over time, though variants do exist. Three-dimensional Petri dishes, for example, have helped researchers recreate the complex spatial arrangement of human cells, and Petri dishes with two or more compartments allow scientists to study interactions among distinct species of microbes. Single-use plastic has replaced glass over time, contributing to the problem of research waste. Despite these changes in design and material, the association of Petri’s name with shallow lidded containers has persisted over time.

Glossary of Terms

Gymnasium

A secondary school in the Central European context that prepares students for higher education. These are often differentiated into three types by the language requirements involved: classical (requiring Latin, Greek, and one modern language), modern (requiring Latin and two modern languages), and scientific (requiring two modern languages with optional Latin).

Back to top

Microorganisms

Also called “microbes,” these tiny living entities include bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea, algae, protists, and parasites. Most (but not all) cannot be seen by the naked eye.

Back to top

Sanatorium

A specialized hospital, usually in a rural setting, where patients could receive treatment for specific ailments including tuberculosis, alcoholism, and hysteria. Sanitoria were especially popular from the late 1800s to the early 1900s.

Back to top

Further Reading

Petri, Julius Richard. 1887. “Eine kleine Modification des Koch’schen Plattenverfahrens” (“A Small Modification of Koch’s Plate Method”). Centralblatt für Bakteriologie und Parasitenkunde, 1: 279–280. (Available at the Biodiversity Heritage Library.)

Shama, Gilbert. 2019. “The ‘Petri’ Dish: A Case of Simultaneous Invention in Bacteriology.” Endeavour 43: 11-16.

Corrado Nai. 2024. “Meet the Forgotten Woman Who Revolutionized Microbiology With a Simple Kitchen Staple.” Smithsonian Magazine (June 2024).

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.

You might also like

SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHIES

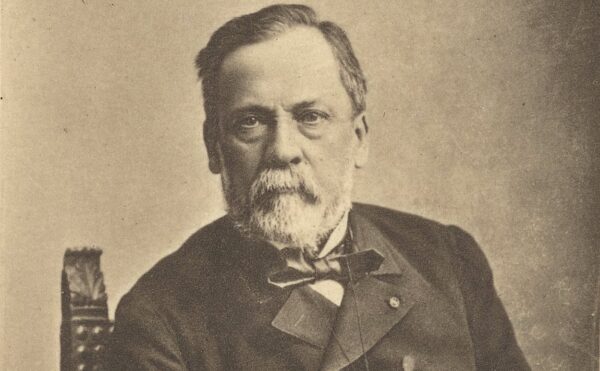

Louis Pasteur

Pasteur demonstrated that microorganisms cause disease and discovered how to make vaccines from weakened, or attenuated, microbes.

EXHIBTIONS

Sensational Science: A Century of Microbe Hunters

This digital exhibition explores the nearly 100-year-old book that influenced generations of scientists.

SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHIES

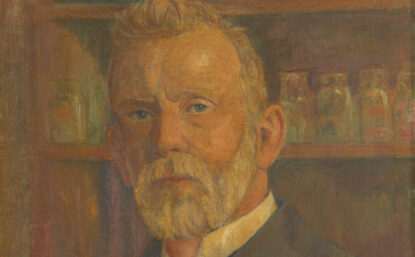

Paul Ehrlich

Nobel laureate Paul Ehrlich conducted groundbreaking research on the body’s immune response and introduced the concept of a “magic bullet.”