Lee W. Riley

Riley was a molecular epidemiologist who dedicated his career to issues of health equity.

Lee W. Riley (1949–2022) pioneered new ways of studying the spread of infectious diseases, based on the genetics of microorganisms. He made significant contributions to global public health, focusing on infection by E. coli, tuberculosis, and issues of health equity. His career was motivated by a desire to take action in the face of human suffering.

Riley grew up with a multiracial identity in several different countries. He was a student of medicine and the humanities, and his life cut across communities of belonging and traditions of thought. He put his compassion for others to work in the practice of science and medicine.

LEARN MORE

The Science History Institute holds Lee Riley’s oral history interview in our collections and produced a short video about his life that is featured in our Voices of Science oral history project. Compare and contrast these representations of his life. Where do they overlap and where do they differ? Which of these windows into his life would you say are “primary sources” and which are “secondary sources?”

Childhood

Riley’s birth name was Hiroshi SATOYOSHI (里吉広). He was born in Yokohama, Japan, to a Japanese mother and a U.S. soldier who was Black. The soldier was only known to his son from a photograph: the Korean War broke out less than a year after Riley’s birth, and many U.S. soldiers, Riley’s birth father included, left Japan for Korea. Riley was one of the thousands of children who were born as multiracial individuals during the U.S. occupation of Japan following World War II.

Many Japanese discriminated against multiracial children because of their skin color. Despite such prejudice, the Satoyoshis—his mother, aunt, and grandfather—raised Riley with love and care. He grew up speaking Japanese as his native language. But in 1958, his mother lost her job at the National Railways, making it difficult for her to care for her son. She made the difficult choice to send nine-year-old Riley to an orphanage outside of Tokyo called Boystown, hoping that a U.S. family would be able to provide a better life. He stayed there for about a year and a half until he was adopted.

Like his biological parents, his adoptive parents—the Rileys—were Japanese and African American. Because his adoptive father worked for the U.S. civil service, Riley spent the rest of his childhood in Thailand, attending an international high school in Bangkok as a U.S. citizen. Years later, he looked back on his adoption, imagining the life he might have had otherwise in Japan. Riley believed that his biological mother made the best of a bad situation: “[T]here was no real possibility that if I grew up in Japan, that I would be able to do what I’m doing now here,” he said of his pathway through life.

Education

Riley often felt that he was between two worlds and that he could never fully belong to either one of them. Wanting to learn more about who he was, he pursued philosophy at Stanford University in 1968. As a part of the campus-based political organizing of the 1960s—including the Civil Rights Movement, the Anti-Vietnam War Movement, and the Free Speech Movement—students of color formed various student unions. Riley often felt he was not fully accepted by either the Black or the Asian student groups. He turned to the study of philosophy, Buddhism in particular, in an effort to better understand his place in the world.

During his college years, Riley spent summers in Thailand teaching English. He had not interacted with Thai people very much during his childhood, and he wanted to learn more about them. In doing so, he came to believe that the country still had not attained the level of medical care available in the U.S., and that its people needed more services. He decided to become a doctor because he believed it would help him solve the problems he witnessed.

In 1972 Riley enrolled at the University of California, San Francisco to study medicine. While he was doing a clinical rotation in a remote village in Thailand, he had another change of heart, one that would forever alter the course of his life. An old man with a chronic lung condition in his care refused lifesaving medicine and passed away. Deeply affected by the encounter, Riley decided to change his career to public health. He felt he could reach more patients at less of a personal cost by focusing on illness prevention.

Molecular Epidemiology

As he shifted from clinical practice to public health, Riley built new skills in molecular epidemiology. This was an emerging field in the 1980s that focused on identifying the sources of diseases in genetic and statistical data. At the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, he became an epidemiologic intelligence service investigator in 1981.

In this role, he investigated the sources of mass food poisoning incidents and learned how to conduct laboratory-based research. Before Atlanta, he had not worked in a laboratory: “I didn’t even know how to hold a pipette at that time,” he later said. Career technicians at the CDC gave Riley informal, on-the-job training. They taught him how to store Salmonella in the refrigerator, among other crucial tasks. With the help of these technicians and other CDC staff, Riley was able to trace the source of a 1982 food poisoning outbreak to fast-food burger patties. The team identified the cause as E. coli O157:H7.

During his time with the CDC, Riley also worked in India, helping local research institutions develop their capacity for scientific research. He assisted scientists who wanted to publish their research in international journals and facilitated the in-house production of fundamental research materials. Riley felt that building local resources for science and medicine would allow Indian researchers to tackle their public health problems with greater autonomy. Through this period of his career, he became increasingly dedicated to combating the diseases prevalent in poor urban communities around the world.

“Slum Health”

In 1996 Riley became a professor of infectious disease and epidemiology at the University of California, Berkeley, where he continued previous work on E. coli and drug-resistant tuberculosis. He also began investigating diseases such as leptospirosis and rheumatic heart disease, which were less prevalent in wealthy countries like the U.S. He had seen firsthand how these were caused by polluted water and untreated infections when visiting São Paolo, Brazil. Riley recognized that people were dying from treatable illnesses, and he determined that these were caused primarily by social factors. He decided to tackle the root causes of preventable illnesses.

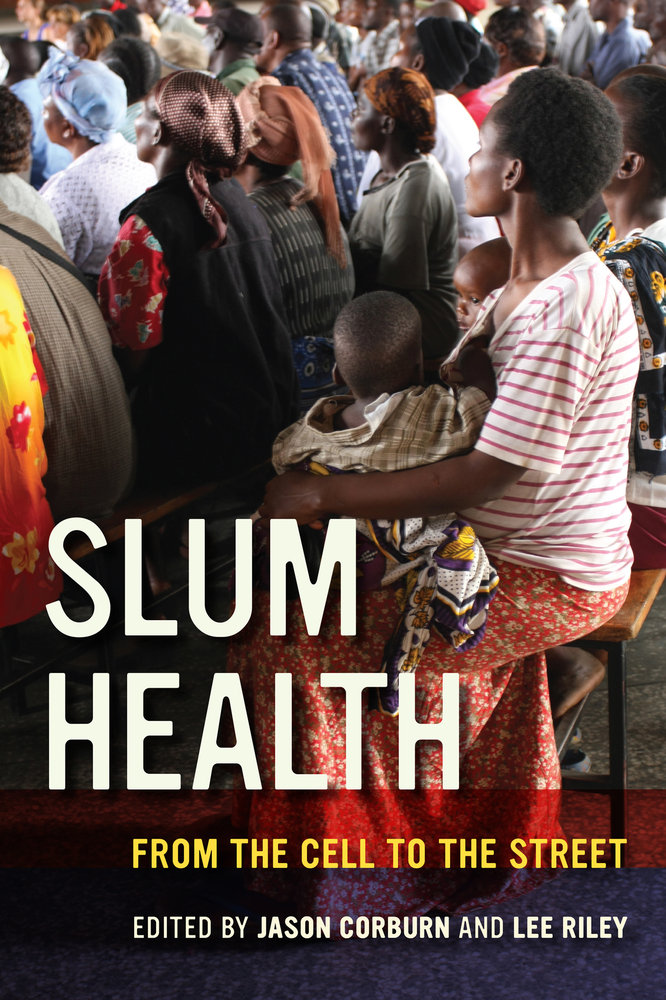

Riley concluded that science alone could not combat infectious diseases in poor communities. In 2016 he introduced the concept of “slum health,” aiming to encourage a more holistic approach to global public health. He formed a team that brought urban planners, medical doctors, patients, and residents together in pursuit of health equity.

Contribution

Lee Riley’s life mission was to do “something meaningful” to ease human suffering. His commitment was rooted in his philosophical curiosity about the nature of human beings. This curiosity led him first to medicine and then to the study of global public health. Riley was comfortable moving between cultures, national traditions, and scientific approaches. His work broke down the distinction between basic research and its application. As he always reminded his students, scientific theories and techniques cannot be proven useful in the lab—they have to be tried out in the “real world.”

Further Reading

Corburn, Jason, and Lee Riley, eds. Slum Health: From the Cell to the Street. University of California Press, 2016.

Riley, Lee W. “Laboratory Methods in Molecular Epidemiology: Bacterial Infections.” Microbiological Spectrum 6 (2018): 1–23.

Riley, Lee W. “Interview with Dr. Lee Riley.” Berkeley Scientific Journal 14, no. 1 (2010): 28–37.

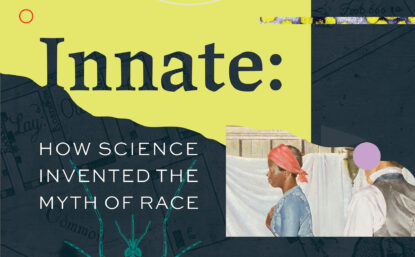

Tamai, Lily Anne Welty. “Checking ‘Other’ Twice: Transnational Dual Minorities.” Red and Yellow, Black and Brown: Decentering Whiteness in Mixed Race Studies. Rutgers University Press, 2017.

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.

You might also like

DISTILLATIONS PODCAST

Exploring ‘Health Equity Tourism’

With a new public interest in health equity research, who is actually receiving recognition and funding in the field?

SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHIES

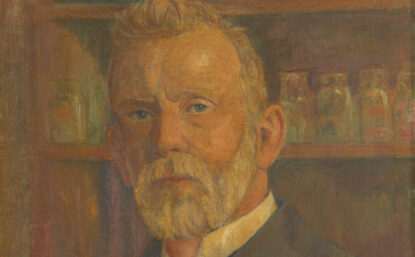

Paul Ehrlich

This Nobel Prize-winning biochemist introduced the concept of the “magic bullet.”

EXIBITIONS

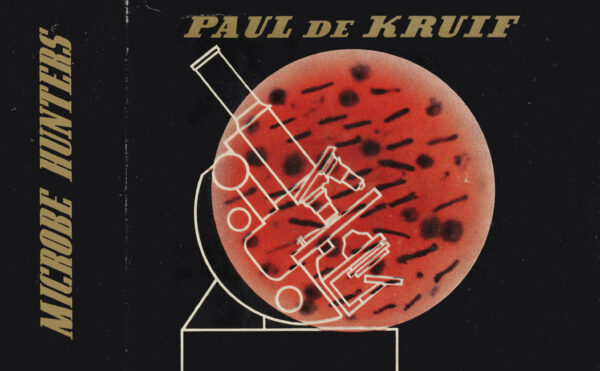

Sensational Science: A Century of Microbe Hunters

A digital and outdoor exhibition exploring the nearly 100-year-old book that influenced generations of scientists.