Margaret Lucas Cavendish

Cavendish authored more than 20 books about nature. She used her prominent social position to challenge gender and scientific norms of the 1600s.

Margaret Cavendish (1623–1673), Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, was a prolific author who contributed to early debates about matter and life in natural philosophy—a field that we today would call “science.” She combined reasoned argument with observational data in her writing. Through experiments with poetry, plays, science fiction, and other genres, she welcomed women, among others, to investigations of the natural world.

Education and Civil War

Cavendish was born Margaret Lucas, the youngest of eight children, to Sir Thomas Lucas and Elizabeth Leighton. The family was well-off; Margaret was privately tutored and an enthusiastic reader. She also benefitted from the more formal education one of her brothers received. As she later recalled, “[W]hen I read what I understood not, I would ask my brother, the Lord Lucas, he being learned, the sense of meaning thereof.”

There was great turmoil in England during Margaret’s lifetime. During the English Civil Wars (1642–1651), the Royalists, who supported King Charles I, fought against the Parliamentarians, who did not. Early on, Queen Henrietta Maria left London for the relative safety of Oxford; its campus was transformed into a defensible fortress. The Lucas family were Royalists, and their home was attacked during the war. This prompted Margaret to travel to Oxford in 1643 to join the Queen’s court. As fighting continued and Oxford became less safe, the court fled again to France in 1644, where the Queen had been born.

Margaret Lucas met William Cavendish, Marquess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (later the first Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne), in France the following year. They married after an eight-month courtship. William was 30 years older than Margaret; he and his brother, Charles, were well-established in literary society, hosting the discussion group known as the Newcastle Circle. Meetings welcomed renowned thinkers like René Descartes and Thomas Hobbes. Margaret Cavendish contributed to debates about everything from the structure and movement of matter to health and politics at these meetings.

The Cavendishes lived in Paris, then Rotterdam, then Antwerp, finally returning to England after the Restoration in 1660, when Charles II, son of Charles I, who had been executed in 1649, was restored to the English throne.

“If my writing please the readers”

Women authors in Cavendish’s time were rare. When they did write, they generally focused on domestic topics, and they typically wrote anonymously. In comparison to those of her contemporaries, Cavendish’s first book, Poems and Fancies (1653), stood out in several ways. The cover page, for instance, highlighted her name and title. The book also used poetry rather than prose to communicate scientific ideas. Cavendish had this to say about the telescope:

“Yet we do take great pains in glasses clear /

To see what stars do in the sky appear. /

But yet the more we search, the less we know, /

Because we find our work doth endless grow.”

In the preface, Cavendish explained her choice of genre. “[P]oetry,” she wrote, “which is built upon fancy, women may claim as a work belonging most properly to themselves.” By appealing to fancy, or creative imagination, Cavendish aimed to reach broad audiences rather than scholars alone: “[I]f my writing please the readers, though not the learned, it will satisfy me,” she declared.

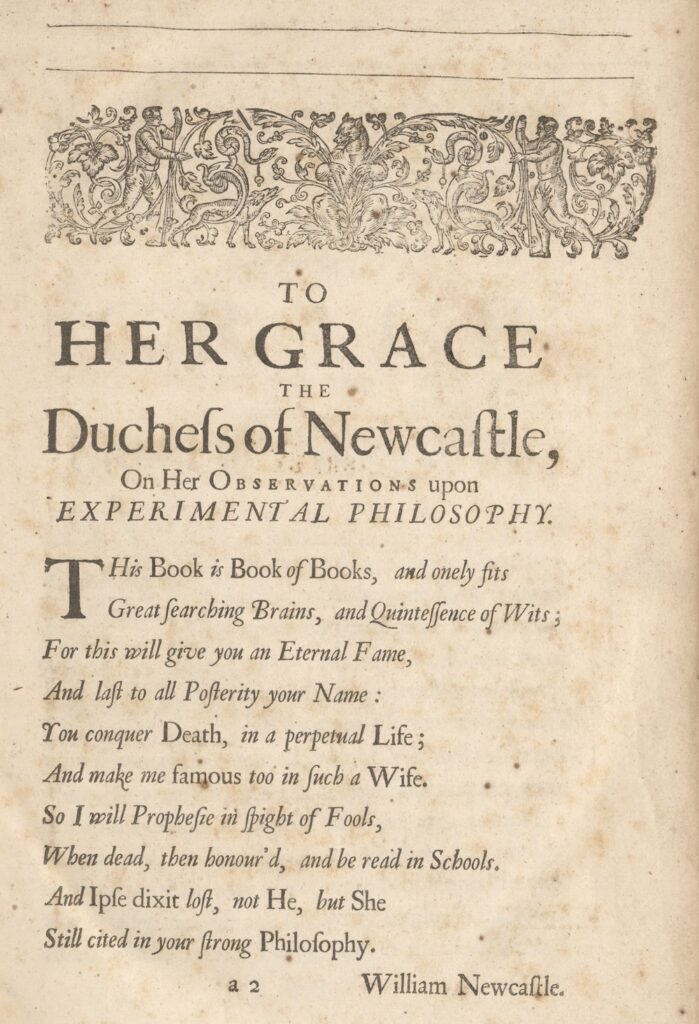

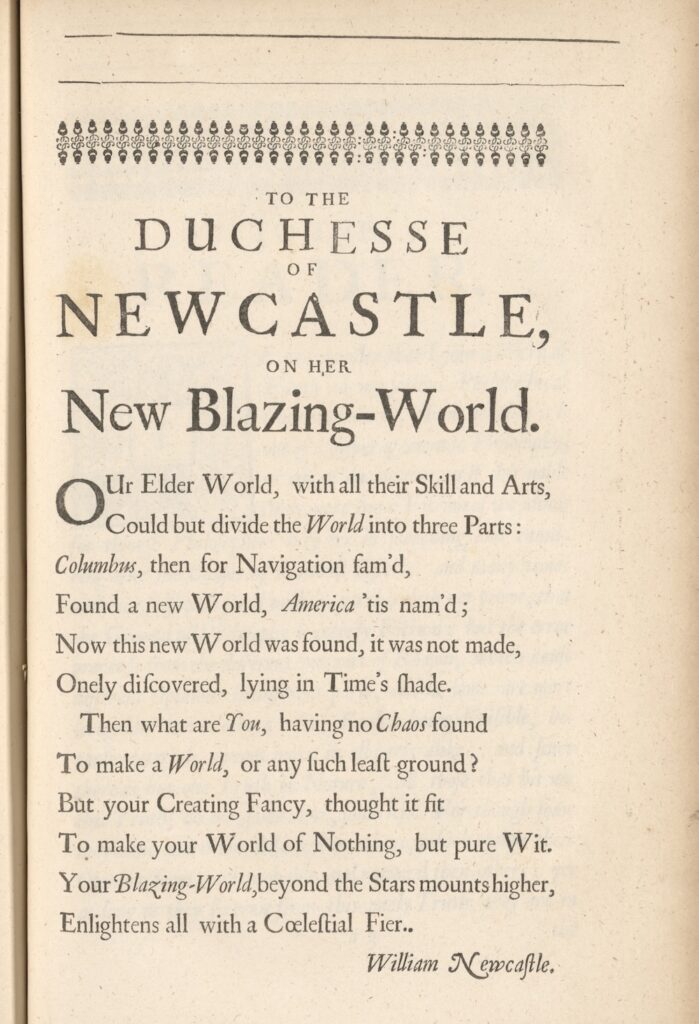

William Cavendish’s prefatory poems to Observations upon Experimental Philosophy and The Blazing World, 1666.

William Cavendish championed his wife’s endeavors, writing prefaces for her books, which he also supported financially. He similarly encouraged his daughters, Jane and Elizabeth (born by his first wife, who died in 1643), to publish their writing. William and Margaret Cavendish could not have children of their own, so Margaret devoted her time to writing instead. She became known in London for both her books and her unconventional clothing. She later reflected that she “took great delight in attiring, fine dressing, and fashions, especially such fashions as I did invent myself . . . for I always took delight in a singularity.”

Critique of the “New Science”

In 1666, Cavendish published Observations upon Experimental Philosophy: To which is added, The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World. The first part of this work considered common debates in natural philosophy. One debate was between Nature (observed by the senses alone) and Art (observed with the aid of scientific instrumentation). Cavendish favored Nature.

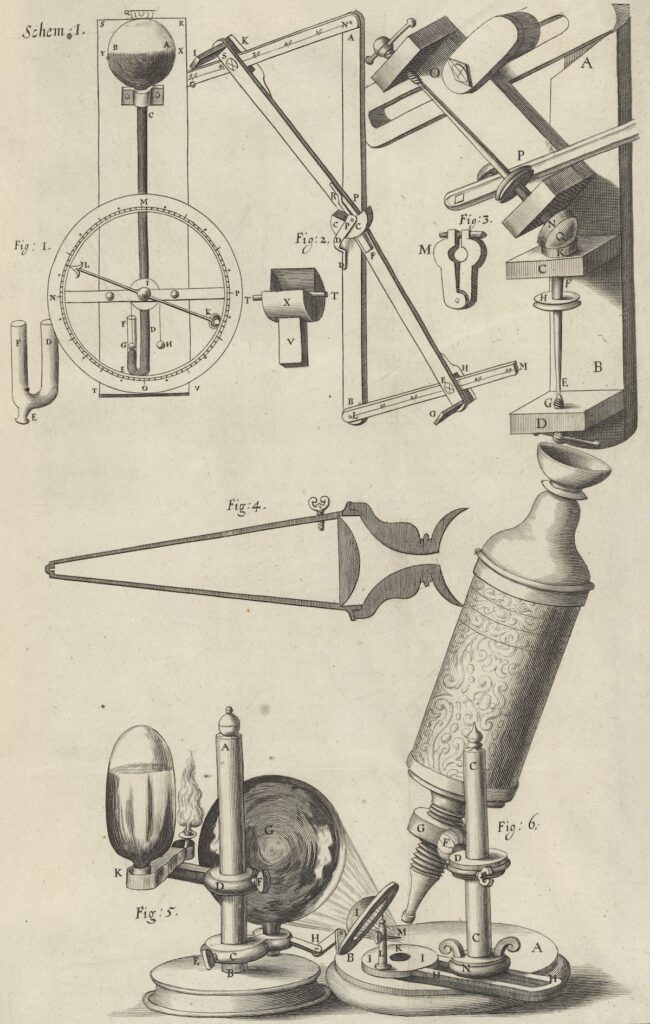

She responded, for instance, to Robert Hooke’s then-cutting-edge Micrographia and its praise of the microscope. Because she had used microscopes in the Cavendish household, she could speak to their potential drawbacks. For example, she noted how a cracked lens distorted an object, rather than enlarging it. Elsewhere, Cavendish emphasized clarity in scientific writing: “[I]f anyone intends to write philosophy […], he ought to consider the propriety of the language, as much as the subject.” Cavendish expressed her preference for writing in English, not Latin, and for avoiding mathematical symbols.

The second part of the book, The Blazing World, was a pioneering work of science fiction. Here, Cavendish described a woman who travels to a new land, ultimately becoming Empress. The Empress encounters a variety of human-animal hybrid creatures in this civilization, each representing a different scientific discipline: “The Bear-men were to be her Experimental Philosophers, the Bird-men her Astronomers,” and so on. She consults with the creatures on scientific questions to improve society, exhorting them to “busie your selves with such Experiments as may be beneficial to the publick.”

Cavendish singled out women readers in the preface to her book, stating “most Ladies take no delight in Philosophical Arguments, [so] I separated some from the mentioned Observations, and caused them to go out by themselves . . . in presenting to Them such Fancies as my Contemplations did afford.” In so doing, Cavendish used another unexpected genre to convey content, anticipating perspectives of science communicators today, who often seek to expand the scope and audience of science through new media.

LEARN MORE

Did you notice that this biography is written in prose? What if it had been written in poetry, as Cavendish might have done? Would meaning be gained? Lost? For whom? Every word in a text is a choice that could have been otherwise. Compare what you’ve learned about Cavendish so far to a poetic rendering of her life: are there particular words or phrases that remind you of details in her biography?

Skillfully, willfully: Margaret Cavendish

Writes across borders – prose, science, and rhyme—

Uncompromisingly, steady-surprisingly,

Geopolitic’ly varied in clime.

Opening doors via new metaphors, see a

Span philosophic: minute to sublime;

Concepts wide, raising, through fictional phrasing.

Her New World, set blazing, will stand throughout time.

Seeing her words with this art interspersed:

What new facts strike your fancy? What interests are prime?

Genres wide-ranging, ideas exchanging,

In voice of the Duchess, Newcastle-on-Tyne.

The communities and discussions satirized in The Blazing World were based on London’s newly formed Royal Society. Cavendish, who had become acquainted with Society members through the Newcastle Circle and written correspondence, requested a visit and was invited to attend on May 30, 1667. That day, she saw experiments on optics, magnetism, and chemical reactions; she also observed Robert Boyle’s demonstration of the air pump. Cavendish’s visit came nearly three centuries before the first women were elected to membership in the Royal Society in 1945.

Cavendish died in 1674 and is buried in Westminster Abbey alongside her husband. Her contributions to philosophy and the history of science have attracted great interest in recent decades, especially as her writing has been examined in its entirety. She remains a singular example of someone who used her privilege to challenge male authority over knowledge of nature.

Further Reading

Boyle, D. The Well-Ordered Universe: The Philosophy of Margaret Cavendish. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Cunning, D., Ed. Margaret Cavendish: Essential Writings. Oxford University Press, 2019.

Holmes, R. This Long Pursuit. HarperCollins, 2016.

Peacock, F. Pure Wit: The Revolutionary Life of Margaret Cavendish. Pegasus Books, 2024.

Walters, L. and B. R. Siegfried, Eds. Margaret Cavendish: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Wilkins, E. “Margaret Cavendish and the Royal Society.” Notes Rec. 2014, 68, 245-260.

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.

You might also like

DIGITAL COLLECTIONS

Women & Science Collection

Materials related to notable women scientists as well as images of women working in a variety of laboratory and industrial settings.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

First Lady

In 1667 Margaret Cavendish was the first woman allowed to visit the all-male bastion of the Royal Society, a newly formed scientific society. Who was this woman?

SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHIES

Jane Marcet

‘Conversations on Chemistry,’ written in 1806 by Marcet, was intended for girls, but it also introduced chemistry to boys like Michael Faraday, whose formal education was very limited.