Margery Milne

A biologist and ecologist who dedicated her life to popular science writing and environmental preservation.

Margery Joan Greene Milne (1914–2006) was a gifted writer and an educator. She worked alongside her husband to share stories of science with people of all ages so that they could gain an appreciation for nature and environmental stewardship. She was known for her ability to appeal to broad audiences, making complicated scientific writing accessible to all.

The Beginning of a Lifelong Adventure

Margery Greene was born near the Bronx Zoo in New York City. Her father was a salesman who loved to gamble on horses. When times were flush, the family would go to the theater and concerts in Central Park; when money was tight, they barely had enough for groceries. She learned to find beauty in the smallest things and discovered her love for the natural world early on. Of her childhood she remembers: “There was so much to see and so little money to spend to get pleasure and learning.” When she was not exploring the Bronx Zoo, which was free at the time, she would hear stories about plants and animals from her father and her aunt, who was a biology teacher. Throughout her childhood, Margery and her family read the New York Times. She particularly enjoyed the Book Review section and started dreaming of writing books, hoping that one day she would find her own work reviewed in the newspaper.

Initially, Margery struggled in school. She would stare out the window, “looking at the field filled with daisies, black-eyed Susans, and apple trees,” and dream of exploring the world. But by the time she got to high school, she had discovered her passion for learning and excelled in biology and Latin. After graduation, she applied to Hunter College, where she was awarded a tuition waiver for high grades and elected president of the Honors Biology Society. She earned her BA in 1933. Her passion for science led her to Columbia University, where she passed the master’s level teaching exam with highest honors. She became a biology teacher back where her love for nature started: at Theodore Roosevelt High School in the Bronx.

During a summer research trip to the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, in 1934, Margery met her future husband, Lorus J. Milne (1910–1987), a Canadian who was studying for his PhD at Harvard University. They were drawn together by their love of the outdoors, their fascination with creatures small and large, and their passion for scientific research. She decided to pursue her PhD in biology at Radcliffe College, a women’s college in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She won a fellowship that paid her tuition, was elected a member of the Phi Beta Kappa Honor Society, and earned her PhD in 1939. Greene married Lorus Milne in 1936, and with her MA in hand, accepted a faculty position at the University of Maine, while her husband accepted a position at Southwestern University in Texas.

When Lorus came to visit Margery in Maine for a delayed honeymoon (around 1937), the couple hiked up Mount Katahdin. Lorus fell and tore a ligament in his knee, but this accident turned out to be a blessing in disguise. There was insurance money left over after his treatment, and they used it to buy a camera. This camera allowed them to start taking photos (later, videos) of the natural world. It led to their first national publication for the New York Times in the early 1940s: an illustrated story of moose and their young, which they photographed during a summer in Wyoming. Margery later recalled, “This was the beginning of our success in photography and writing. Careers are born in strange ways.”

After living apart for several years, the couple relocated first to Virginia and then to Philadelphia. Margery accepted a position at Beaver College (now Arcadia University) and Lorus began teaching at the University of Pennsylvania. Later, they would accept positions at the University of Vermont (1947) and at the University of New Hampshire (1948) in Durham, where they lived for the rest of their lives.

Studying Burying Beetles

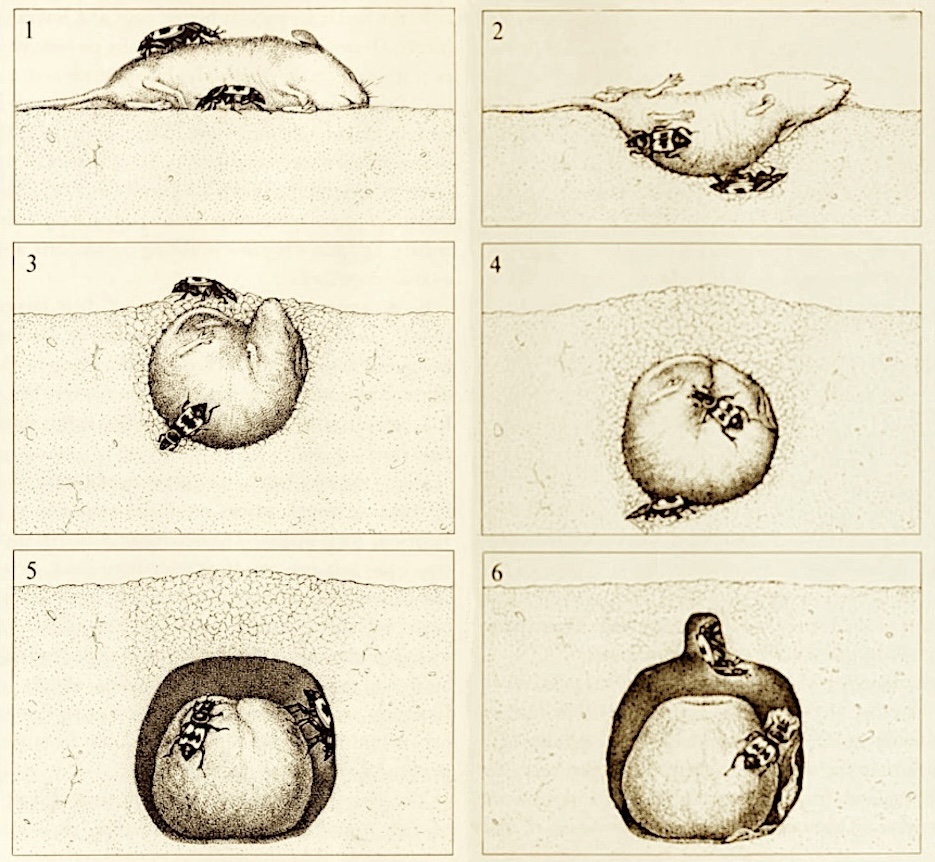

The Milnes would often dedicate free time and vacations to scientific explorations. During a six-week vacation in Ontario, Canada, Margery and her husband decided to observe the behavior of orange and black burying beetles, scientifically known as Nicrophorus (Coleoptera, Staphylinidae, Silphinae). Lorus was an enthusiastic entomologist, and little was known about the beetles’ behavior. They decided that the research represented a unique opportunity to make a major scientific contribution. They were fascinated by how such small insects care for their young. They observed the beetles burying, mummifying, and feeding the bodies of mice, birds, and snakes to their tiny offspring. The Milnes spent their nights tracking and photographing the beetles’ activities, publishing their findings in the Journal of the New York Entomological Society in 1944.

Thrilled to share their discoveries about the beetles with the world, Margery gave lectures at such institutions as the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences. Encouraged by a colleague to share their stories with a broader audience, she wrote an article with her husband for the prestigious Atlantic Monthly on these “insect gravediggers” in 1945. This set the stage for the Milnes’s entry into popular science writing. Their work appeared in several national magazines, including National Geographic, Audobon, and Reader’s Digest.

The Milnes continued to study beetles for many decades. Back home in New Hampshire, they invited children in the neighborhood to gather dead birds and small animals so they could study the burying behavior of Nicrophorus. When they saw how fascinated their research assistants were with the insects, they wrote Nature’s Clean-Up Crew, a children’s book that won the Junior Literary Guild Award in 1982.

Revealing Nature’s Wonders, Small and Large

Throughout her life, Margery Milne collaborated with her husband on numerous scientific articles and popular books. Together, they co-authored more than 50 books and over 100 journal articles. For these scientists, the smallest details held the key to the biggest questions. By focusing on everyday phenomena like water droplets, they uncovered connections between local and global conditions.

In 1952 the Milnes published their first textbook, The Biotic World and Man, which featured an ecological approach and quickly became a required text in high school and college biology classes nationwide. Ecology as a field was expanding throughout the 1900s, and the concept of human ecology brought awareness to human environmental responsibilities. The Biotic World and Man explored plant and animal life, helping students understand and appreciate planetary ecosystems. The textbook came to the attention of the United Nations Education Council, now known as UNESCO, which invited the Milnes to travel to Australia and New Zealand to conduct further research so that they could update other textbooks in biology. On this trip, the Milnes had the opportunity to explore the Great Barrier Reef and the Gold Coast of Australia, which later inspired a children’s book on coastal life.

The Milnes won a study grant to the Smithsonian Institute’s Barro Colorado Island Sanctuary in Panama, where they documented life in the rainforest while traveling to other Central American countries. Numerous awards for international research and travel followed. Their book, Water and Life (1964), was well received, prompting the National Geographic Society to request further articles. Recognizing their expertise, the Society awarded them a travel grant to explore water-scarce regions, sending them to Israel, Tunisia, Libya, and Kuwait—a stark contrast to the lush rainforests that had first captured their attention.

Tackling Environmental Threats Through Education

Margery Milne brought major environmental topics such as pollution, climate change, ocean health, and radioactivity to broader public awareness. After the nuclear accidents of Three Mile Island (1979) and Chernobyl (1986), the Milnes traveled to Russia to learn more from experts on the ground. They gave talks on radioactivity in the Soviet Union and began another book for young adults, Understanding Radioactivity (1989), responding to growing concerns about the dangers of radioactivity.

LEARN MORE

Margery Milne co-authored this review of Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring, in 1962. Silent Spring drew broad public attention to DDT, a toxic pesticide. As you read the review, ask yourself: What were the different positions taken in this debate? Did the Milnes agree with Carson or not? What words did they use to show their support or criticism of the book?

Margery Milne urged readers to take action—to restore and protect ecosystems, such as forests, marine habitats, and wetlands that are essential to sustain life on Earth. She and Lorus attempted such environmental preservation locally, in Durham, New Hampshire, where they purchased two acres of land, now known as the Milne Nature Sanctuary. Shortly after, they adopted a mute swan and found her a mate. The swans reproduced and established generations on an adjacent pond, which drew significant local attention. Town officials appointed Margery Milne the “Durham Swan Keeper.”

LEARN MORE

The Milne Nature Sanctuary offers a place for observation and quiet contemplation. What can you learn from observing nature first hand? How can you use your senses—smell, touch, sound, and sight—to learn more about the world around you?

Perseverance in a Sexist Scientific World

Margery Milne distinguished herself at a time when it was difficult for women to secure top jobs in the sciences. After World War II, both she and her husband were offered faculty appointments at the University of New Hampshire. But three years later, the university enforced a rule that did not allow family members to be employed at the same institution and she was forced to resign. She eventually cobbled together positions at a number of smaller schools in the area.

Undaunted by life’s challenges, Margery pursued her dream of becoming a writer and an advocate for science education and environmental preservation. Though she only appears as second author on joint publications with her husband, and sometimes not at all, she was the one who convinced her husband to pursue new projects and to travel the world. After her husband died in 1987, Margery Milne continued teaching and writing. She completed two books begun with her husband, Understanding Radioactivity (1989) and Insects and Spiders (1991), and carried out fieldwork on her own until her health no longer allowed her to do so.

Further Reading

Lykknes, Annette, Donald L. Opitz and Brigitte van Tiggelen. For Better or for Worse: Collaborative Couples in the Sciences. Springer-Verlag, 2012.

Milne, Lorus and Margery Milne, “Notes on the Behavior of Burying Beetles (Nicrophorus Spp.)” Journal of the New York Entomological Society, Volume 52 Number. 4, December 1944, pages 311–327.

Milne, Lorus J. “Sexton Beetles.” Accent on Living Section. Atlantic Monthly. November 1, 1945, pages 129–132.

Milne, Lorus and Margery Milne. “There’s Poison All Around Us Now.” Book review of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, New York Times, September 23, 1962.

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.