Paul de Kruif

The bacteriologist and Microbe Hunters author sensationalized science for popular audiences.

Paul de Kruif (1890–1971) was a bacteriologist, army physician, author, and public health advocate. While he spent his career seeking a wide range of reforms in medical research and practice, he is best remembered for his 1926 bestselling book, Microbe Hunters, which inspired generations of curious young readers to pursue scientific careers. The book, which is a collective biography of early adventurers in the field of bacteriology, can tell us a lot about the history of science. But de Kruif’s own story is also revealing. It shows us how biographers often use historical figures to champion their own causes.

Childhood and Education

Paul de Kruif (pronounced like “life”) was born on March 2, 1890, in Zeeland, Michigan. Growing up in a strict Dutch immigrant household and a Calvinist community, de Kruif clashed with rigid social structures and the perceived hypocrisy of religious figures in his life, including his pious but wrathful father, Hendrick. While navigating his studies at the Hope Preparatory School and the Second Reformed Church, de Kruif explored forbidden behaviors (such as swearing) and ideas (such as evolution and atheism). His mother, Hendrika Kremer de Kruif, was an avid reader who encouraged Paul’s love of literature from a young age. Together, mother and son enjoyed “secular” books they knew religious authorities in their lives would not condone.

Although his father wanted him to become an engineer, de Kruif developed an interest in medicine through his friendship with Thomas G. Huizinga, the town doctor. In 1908 he began classes at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor; by 1910 he had transferred to the University’s medical program. While taking a required class taught by Frederick Novy, a bacteriologist known for his work on spirochetes, de Kruif decided to change course. He idolized his instructor’s painstaking laboratory practice and wanted to become a bacteriologist too. De Kruif worked in Novy’s lab throughout the remainder of his undergraduate and PhD studies at Michigan, examining immune responses to various disease-causing agents. After serving in the U.S. Army on the Pancho Villa Expedition and in World War I, de Kruif returned to the University of Michigan in 1919 as an assistant professor of bacteriology. He continued working in the Novy lab, turning his attention to the bacteria that cause strep throat.

Rockefeller Institute

In 1920 opportunity came in the form of a research position at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York, which was the most distinguished institute for medical research in the United States at the time. The move to New York yielded more than a prestigious research position, however. It also connected de Kruif with the New York literary scene, then dominated by authors such as John Steinbeck and Ernest Hemingway.

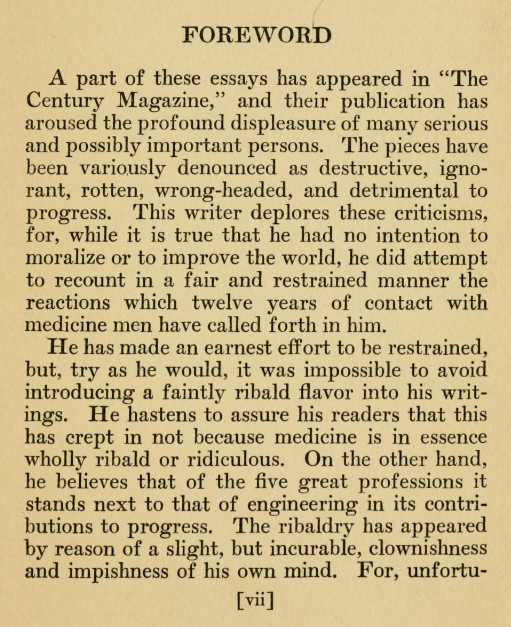

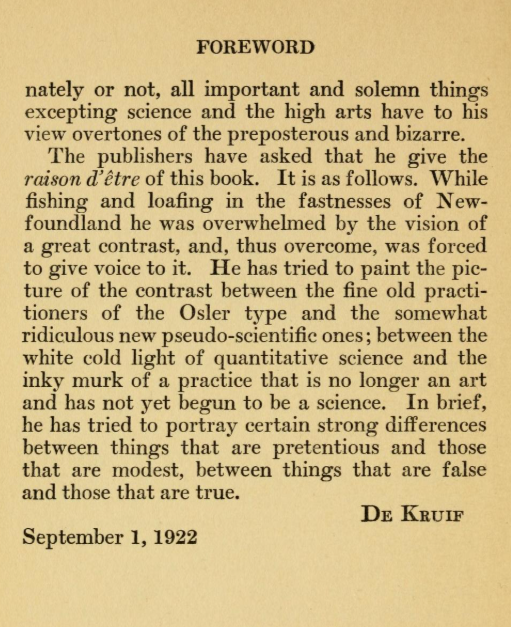

While at the Rockefeller Institute, de Kruif grew disillusioned with both research and medical practice. He wrote articles condemning the corruption he saw in the field—attacking con artists selling false cures and doctors and researchers who cared more about profits than scientific rigor. Two of his most controversial pieces appeared in 1922. The first was a chapter on medicine in the anthology, Civilization in United States, which criticized both quack practitioners and those doctors who steered patients towards expensive treatment options. The second was a serial on unscientific medical research in The Century Magazine, which took aim at his Rockefeller colleagues. When de Kruif’s supervisor, Simon Flexner, learned he was the author of these essays, he responded defensively to them as an attack on the character of the Rockefeller Institute, rather than as a call to action. He fired de Kruif, exiling him from laboratory research (temporarily) and pushing him onto the literary scene.

Foreword to Our Medicine Men (1922). The articles in The Century Magazine mentioned above were subsequently published as this book. In addition to his “clownishness” and love of controversy, note the interesting distinction de Kruif makes here between science and art.

Writing Rebels

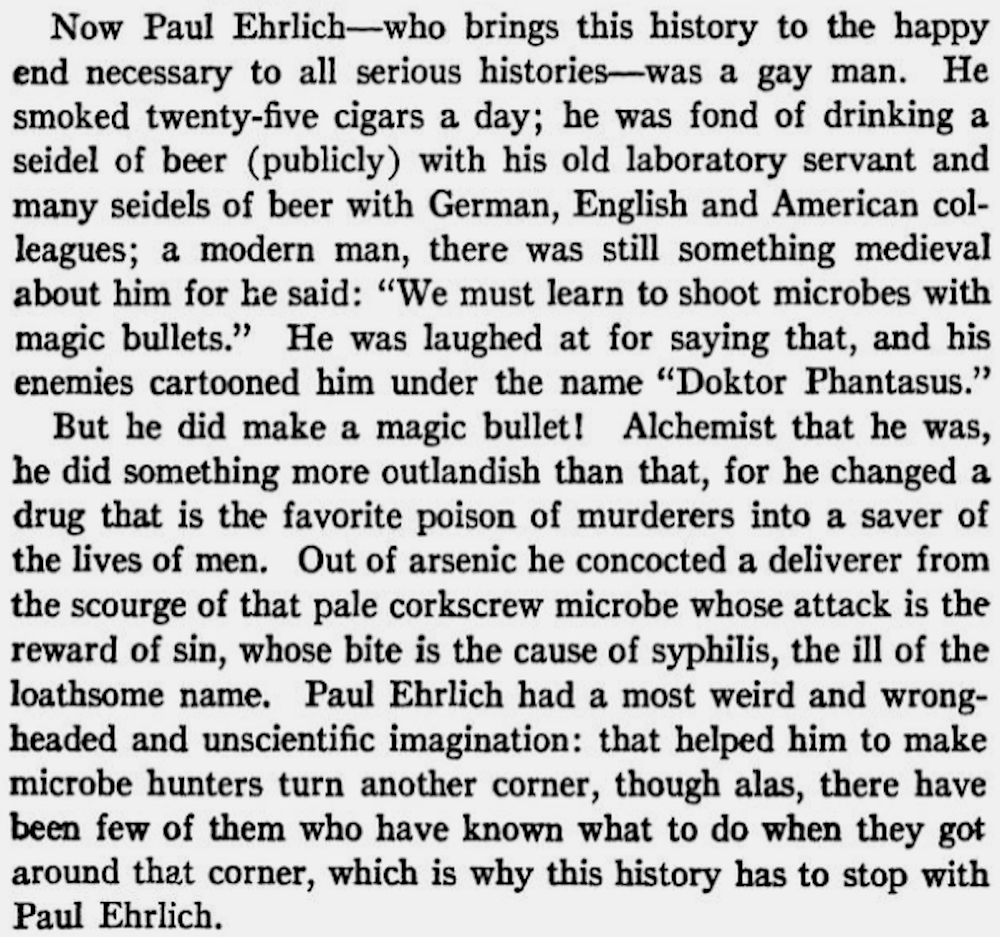

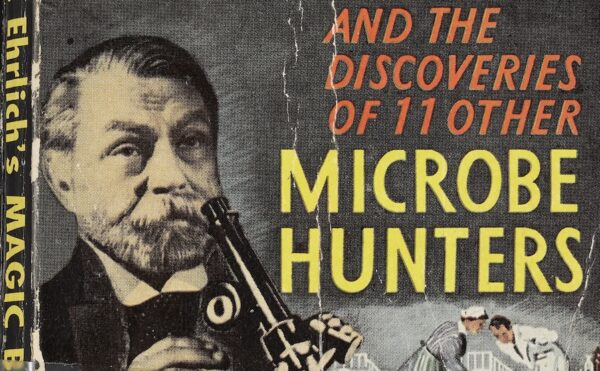

De Kruif’s next two projects gave readers heroes, not villains, of the medical field. First, he introduced them to the fictional Martin Arrowsmith (the title character of Sinclair Lewis’s 1925 Arrowsmith) with stories based on his own career. He published Microbe Hunters, a collection of colorful portraits of bacteriologists including Louis Pasteur and Paul Ehrlich, the following year. Through fictional and historical subjects, de Kruif celebrated the rebel scientist in opposition to the doctors and researchers he criticized in his exposés: these men (and one woman) were bold, staunchly anti-establishment, and willing to sacrifice everything—even patient lives—in the name of science.

As Arrowsmith and Microbe Hunters grew in popularity, de Kruif sought stories of rebel-heroes in broader fields. He regaled popular audiences with the efforts of unknown farmers who developed controls against grain and livestock diseases in Hunger Fighters (1928). In Seven Iron Men (1929), he chronicled a property dispute between the Merritt brothers and John D. Rockefeller, the industrialist who profited from the brothers’ discovery of Minnesota iron ore. In Men Against Death (1932), de Kruif returned to medicine, celebrating researchers whose risky experiments identified causes and treatments for a variety of maladies including diabetes, syphilis, and tuberculosis. Throughout these accounts, de Kruif put his own words and ideas into the mouths of his biographical subjects, often inventing dialogue meant to humanize and valorize scientists for popular audiences.

LEARN MORE

Think about how Paul de Kruif describes Paul Ehrlich in Microbe Hunters. What does he want readers to know? How does this passage (below) compare to other biographies of Ehrlich, for example this one from the Institute’s Scientific Biographies?

Depression-Era Advocacy and Research

After the stock market crash of 1929, poverty was rampant; food and medical services were scarce. Marking a major shift in his career, de Kruif began writing and campaigning about these issues, focusing on wealth inequality, malnutrition, and the insufficiency of state public health services. He adopted socialist viewpoints and campaigned to expand access to testing and preventative medicine for whooping cough and tuberculosis. All the while, de Kruif continued writing.

With Why Keep Them Alive? (1936), he opposed the growing belief that the poor did not have the right to have babies or social services. In The Fight for Life (1939), de Kruif citied recent advancements in protections against death in childbirth, syphilis, and tuberculosis to argue that a disease-free future was on the horizon for all people of all classes, if only they were made accessible to everyone.

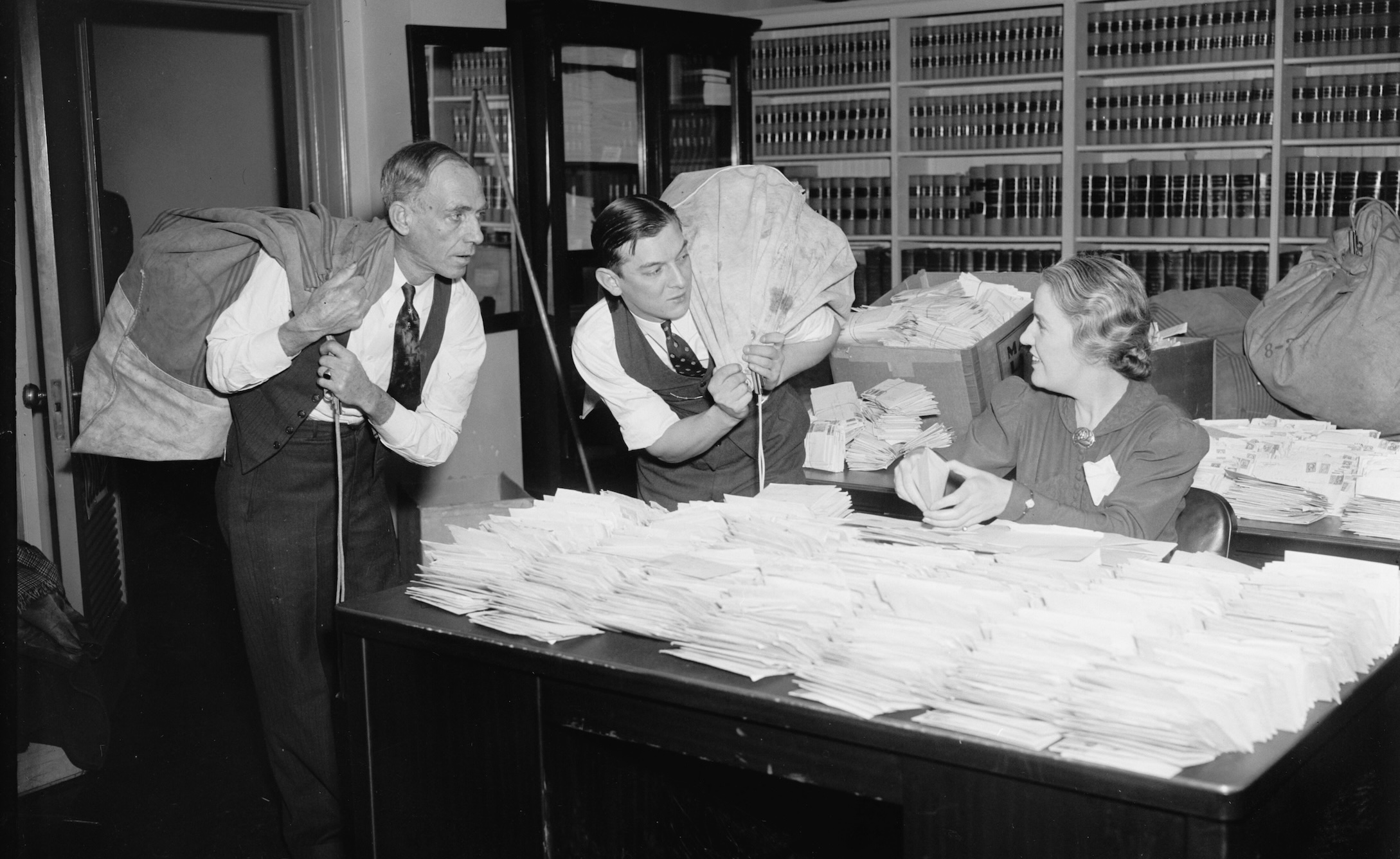

De Kruif also became heavily involved in the nationwide campaign against polio, a viral disease known for causing paralysis, especially among young children. Appointed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Birthday Ball Commission for polio prevention in 1934, and then to the role of secretary of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIP) in 1938, de Kruif built a network of laboratories and research teams to fight the disease. Although he left the NFIP in 1941, de Kruif kept up with polio vaccine research. This work was often contentious and led him into conflict with members of the NFIP and individual researchers.

Promoting Novelty

In the 1950s de Kruif turned his attention to promoting new treatments for a variety of maladies. Writing for popular outlets such as Reader’s Digest, Ladies’ Home Journal, and the Country Gentleman, he encouraged readers to seek new vitamins, antihistamines, and other commercially available products. By now, public audiences trusted de Kruif as an authority willing to go where their doctors would not. These articles broke with de Kruif’s earlier emphases on repeated testing and scientific “truth.”

While maintaining an anti-elite stance, he now challenged doctors who were hesitant to adopt untested drugs by putting decision-making authority directly in readers’ hands. To the dismay of doctors and professional medical organizations, de Kruif’s articles were widely read and built demand for many novel treatments, some of which were subsequently shown to be ineffective.

LEARN MORE

This passage (below, right) comes from Paul de Kruif’s memoir, The Sweeping Wind. Writing in 1962, de Kruif explains his complicated relationship with medicine and research many decades earlier in the 1920s. What reason does de Kruif give for his pivot from medicine to bacteriology? How might that explanation inform his criticism of other practitioners in his public-facing writing? Do you think de Kruif’s life experiences between the 1920s and the writing of this memoir in 1962 shaped his memory of his early-career beliefs? Why or why not?

Revisiting Biography

Biographers always bring parts of themselves to the stories they write. In addition to his research and writing, de Kruif was known to have had a messy personal life that involved several affairs and a struggle with alcoholism. He identified, in turn, with the scandals and controversies in his subjects’ lives. This meant calling attention to their personal flaws as well as their achievements, a decision that got him in trouble with those who were still alive (for example, the British microbiologist Ronald Ross, who threatened a libel suit for the way de Kruif portrayed his competition with colleague, Battista Grassi).

At the same time, the personal (some would say, invasive) style of de Kruif’s writing is part of what seduced wider audiences. He gave readers microbe hunters who were multidimensional and relatable. He turned them into crusaders for his public health goals, the kind of crusader he himself wanted to be.

De Kruif concluded Microbe Hunters with an admission of this personal investment. He wrote:

In the years since he wrote these words, de Kruif himself became the subject of remembrance. Various writers have contributed biographies—long and short—that seek to retell and define his life. But these works and the biography you are reading now are useful reminders that remembering itself is a human activity, full of choices and subject to critical reflection.

Glossary of Terms

Spirochete

A type of bacteria known for its helically coiled (spiral) shape.

Back to top

Pancho Villa Expedition

A 1916–1917 U.S. Army operation intended to capture Mexican revolutionary Francisco “Pancho” Villa during the Mexican Border War.

Back to top

Stock Market Crash of 1929

A collapse in United States stock market values that led to the Great Depression. Also known as the Great Crash and the Wall Street Crash.

Back to top

Further Reading

De Kruif, Paul. The Sweeping Wind. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, Inc. 1962.

Emrich, John S. and Charles Richter. “Paul de Kruif and Microbe Hunters.” The Journal of Immunology (January/February 2019) pp. 20-23. American Association of Immunologists.

Tobin, James. “The Michigan Scientist Who Was Arrowsmith.” Heritage Project University of Michigan.

Verhave, Jan Peter. A Constant State of Emergency: Paul de Kruif. Microbe Hunter and Health Activist. Holland: Van Raalte Press, 2020.

Verhave, Jan Peter. “Paul de Kruif: A Michigan Leader in Public Health.” Michigan Historical Review 39, no. 1. Spring 2013. 41-69.

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.

You might also like

COLLECTIONS BLOG

The ‘Microbe Hunters’ Go to School

What a 1932 special edition of Paul de Kruif’s bestselling book reveals about U.S. science education.

SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHIES

Paul Ehrlich

Nobel laureate Paul Ehrlich conducted groundbreaking research on the body’s immune response and introduced the concept of a “magic bullet.”

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

Bug Hunters

In the 1920s author Paul de Kruif turned science into an adventure story.