Vera Katherine Charles

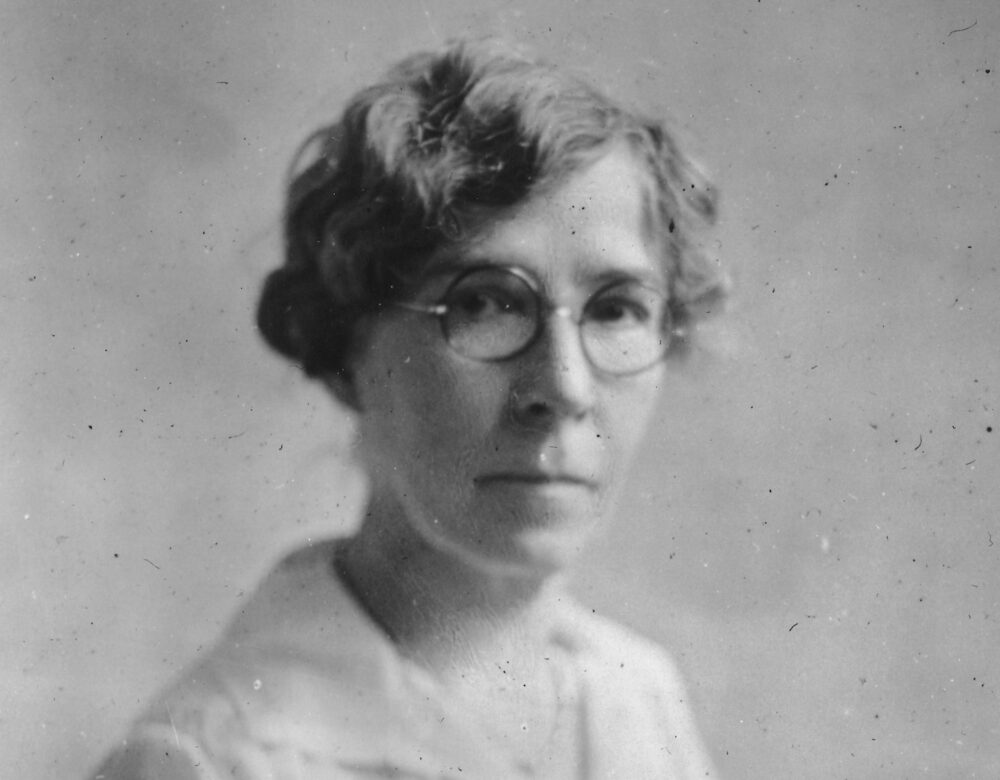

Vera Charles was a pioneer in the study of fungi and one of the first women to specialize in plant pathology at the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Note: This biography follows two separate pathways through the career of Vera Charles, providing multiple perspectives on her life. The main text describes her contributions to mycology. Compare and contrast this with the alternative account in the Learn More section below it, which focuses instead on what her story can tell us about opportunities for women in U.S. science.

Vera Charles: Mycologist

Have you ever wondered about the safety of eating a wild mushroom? Vera Katherine Charles (1877–1954), a trailblazing and dedicated mycologist, author, and collaborator, taught us much of what we know today about edible and poisonous mushrooms.

Studying Fungi

Vera Charles was born in Erie, Pennsylvania, once a hub for shipbuilding, fishing, and transport on the eastern edge of the Great Lakes. After a short time as a non-degree student at Mount Holyoke College, she transferred to Cornell University, earning her undergraduate degree there in 1903. At Cornell, she conducted graduate work in mycology with George F. Atkinson, who was Professor and Chair of the Botany Department. Known primarily for his work on mushroom taxonomy, Atkinson standardized how fungi—a category that includes yeasts, mildews, molds, and mushrooms—were studied and recorded. His work shaped the training of mycologists for generations to come.

Charles joined the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) as a scientific assistant directly after her graduation from Cornell. Within a few years, the scientific honor society, Sigma Xi, recorded her promotion to “assistant mycologist,” referring to her expertise in the theoretical study of fungi. In this capacity, she worked in the Office of Mycological Collections, focusing in particular on Agaricaceae, the family that includes the common “button mushroom” found in supermarkets today.

Becoming Food

For most of human history, mushrooms consumed for food were collected from the wild. By the early 1900s, mushrooms were present, but not yet common, in the U.S. diet. Consumption varied widely by household and opinions on their edibility differed just as much. Though some believed mushrooms to be nutritious, their consumption was often understood in terms of class: poorer populations were said to eat mushrooms out of necessity while the wealthy might have chosen to eat them based on taste. As one 1917 article reported, “one man will say they are not fit to eat,” while another likened eating a dish of mushrooms to hearing “the violins of heaven singing.”

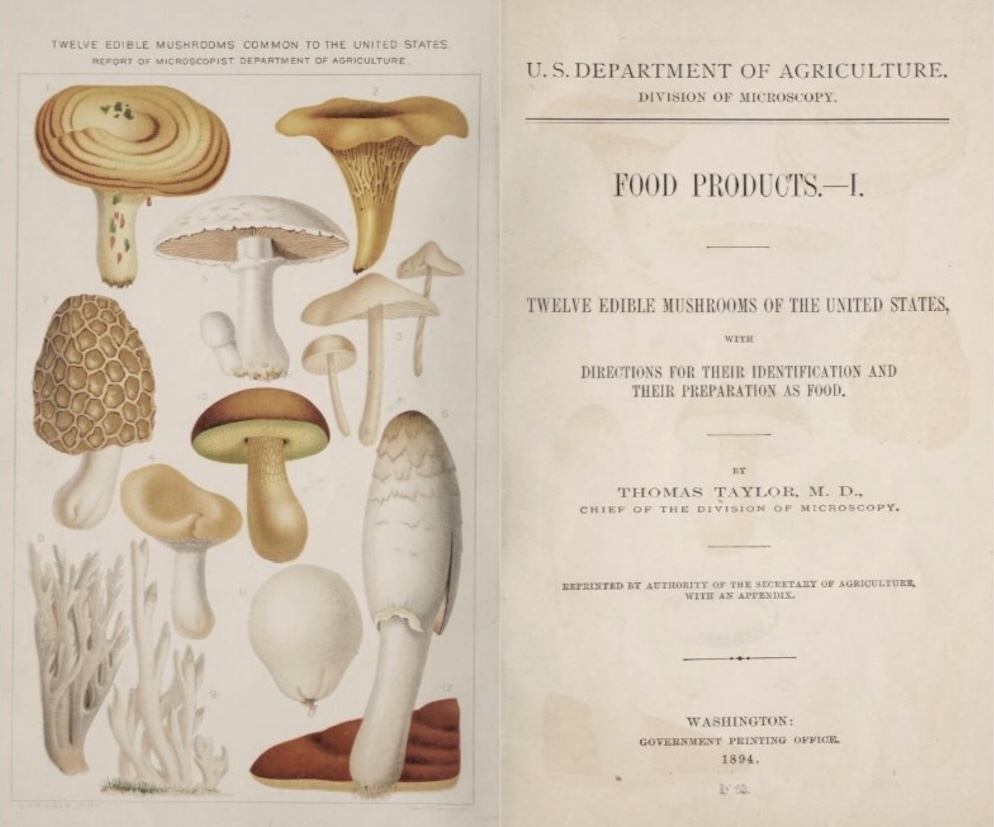

U.S. fears about mushroom poisoning were widespread in the early 1900s, even though death by poisoning was rare. In 1898, the USDA had published a government circular, or newsletter, warning that public education about poisonous mushrooms might be necessary. But this did little to control what people ate. In 1906, the death of a judge in Ohio who accidentally ate poisonous mushrooms, became front-page news. Through the 1930s, newspapers felt the need to remind readers that the only safe way to eat mushrooms was to become an expert in the poisonous varieties or to buy from responsible sellers, like the grocer or delicatessen. They dismissed household practices like the “silver spoon” test, according to which a silver spoon would turn black in the presence of poisonous mushrooms, as mere “superstition.”

Advising Eaters

Charles spent many years studying Agaricaceae and she eventually became an expert in distinguishing poisonous from edible mushrooms. She co-authored the 1915 bulletin, Mushrooms and Other Common Fungi with her co-worker Flora Wambaugh Patterson. A sign of its popularity, the bulletin was re-circulated in 1917.

In 1931, Charles published Some Common Mushrooms and How to Know Them, a USDA bulletin intended to be read by the “amateur collector or nature scientist,” among other audiences. Revised twice in later years, this publication became one of the USDA’s most requested publications during the first half of the 20th century. It aimed to make mushroom identification accessible to the general public.

Charles also wrote Farmers’ Bulletin No. 1587, Mushroom Culture for Amateurs in 1929, which was revised in 1933. It recognized the increasing interest in cultivating mushrooms at home rather than foraging for them in the wild. Here, Charles provided practical yet encouraging advice: “It is best to begin in a small way,” she wrote, “and with a limited financial outlay unless the prospective grower has had some experience with this crop.” She recognized the lack of formal knowledge about mushroom cultivation, noting that “the new grower is generally forced to learn from personal experience.” Changing food preferences in the early 20th century, spurred by global events like the Great Depression, likely contributed to the popularity of these books.

Testifying Mycology

Large-scale mushroom cultivation grew in tandem with the increase in U.S. mushroom consumption during the first half of the 1900s. Improvements in mushroom farming techniques—particularly the adoption of pure-culture spawn and pasteurization of growing beds—dramatically increased yields. As mushroom farming became a more stable and productive industry, industrial farmers and amateur growers consulted Vera Charles for her expertise. Journalists, too, began featuring public health and science topics in this period. Widespread references to Some Common Mushrooms catapulted Charles into the public eye as a national “mushroom expert.”

Mushrooms were valued not only as food, but also for their emerging uses in composting, recycling, and soil conditioning. However, some businesses selling mushroom spawn misled consumers into believing that these fungi could be grown quickly, easily, and for substantial profit. This was especially common before 1950, when less was known about mushroom farming than is known today.

In 1937, Charles served as an expert witness for the government in the Federal Trade Commission’s complaint against American Mushroom Industries, Ltd., a New-York based company accused of engaging in “unfair competition in the sale of mushroom spawn.” The company was accused of false advertising. In her testimony, Charles dispelled the company’s claims of a nationwide mushroom shortage, laid to rest a long-held belief that mushrooms must grow in the dark, and undercut the company’s claims that mushrooms grow overnight. Charles applied her scientific knowledge in a legal setting, contributing to the broader public credibility of her expertise and mycology.

Charles remained dedicated to the study of fungi throughout her life. She prepared descriptions of new species for other authors and maintained an “undiminished interest in current literature in mycology and phytopathology” until her death. Her enthusiasm is palpable in Some Common Mushrooms where she writes, “[t]he hope of finding something new continuously urges one on, and the thrill of possible discovery is ever present.” Her writing spoke to enthusiasts as well as experts, shaping Americans’ relationship with mushrooms in ways that still influence food, health, and agriculture today.

LEARN MORE

Biographers, like all historians, have to make choices about the evidence they use and the stories they tell. Here, we tell two different stories about the life of Vera Charles by emphasizing different sources and texts. You have been reading the story of “Vera Charles: Mycologist.” Compare this to the story of “Vera Charles: Woman Scientist” below. What differences do you notice between the two?

Vera Charles (1877–1954) was plant pathologist, someone who studied the impact of plant diseases on plant and human life. She spent her career in the Bureau of Plant Industry, an agency within the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Her pathway to plant pathology demonstrates one of the ways in which women became professionally involved with science during the early 20th century.

Studies at Mount Holyoke College and Cornell University

Though she was born in Pennsylvania, Charles spent most of her youth outside of Washington, D.C., where she later made her home. She began college as a “special student” at Mount Holyoke College in 1899. By that time, she would have been over 21 years of age, meaning that she was older than the average freshman, thus eligible to start classes as a non-degree student. While little is known about Charles’s early life, this suggests she might have worked as a teacher before beginning her undergraduate education.

Teacher training was one of the main functions of Mount Holyoke at the time, which was established by Mary Lyon in 1837. Lyon herself was the first chemistry instructor at the school, and she established a strong tradition of laboratory research and education on campus. Lyon and her colleagues worked hard to balance rigorous scientific training with strict moral cultivation. As one graduate later recalled, Mount Holyoke “had a scientific trend from the beginning,” one that did not “convert us into agnostics or infidels.” Charles received a strong foundation in chemistry there despite widespread beliefs that educating young women in this way would undermine the moral fabric of society.

Inspecting Imported Plants

After completing her undergraduate education in botany at Cornell University, Charles was hired by the USDA as a “scientific assistant” in 1903. She would spend the next 39 years of her life working in the Bureau of Plant Industry. There, she analyzed commercial and ornamental plants shipped from abroad. She worked closely with Flora Wambaugh Patterson, Edith Cash, and other women who were supported by the Bureau’s director, Beverly Thomas Galloway.

For many women in the 1800s, the responsibility for maintaining a household garden led to an interest in plants and their development. But such interest did not translate easily into a professional career. Those who did pursue scientific careers like Charles and Patterson faced an uphill battle. They were routinely underpaid, for instance, and were often refused membership in scientific societies, where cutting-edge research was presented and discussed. In her work on plant pathogens in the early 1900s, Charles was nevertheless recognized for her contributions to her chosen field: she authored more than 20 scientific publications and participated in professional societies like the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which had few, if any, women members at the time.

Identifying a Foreign Pathogen

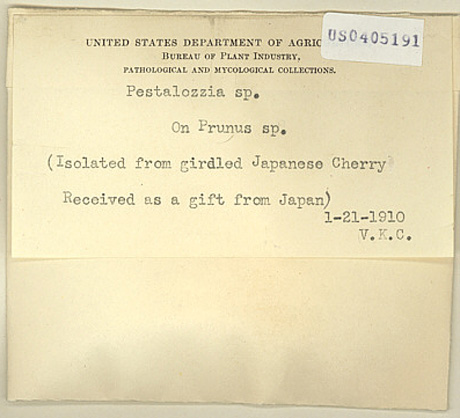

Charles’s expertise in plant pathology reached a new level of national significance in 1909. That year, First Lady Helen Herron Taft decided to plant cherry trees in Washington, D.C. The trees were a powerful gesture of international friendship with Japan at a time when anti-Asian sentiment in the U.S. was high. Inspired by the years she had spent living in the Philippines and organized by chemist Jokichi Takamine, Taft received a gift of cherry blossom trees for West Potomac Park from Japan’s Consul General in New York, Kokichi Mizuno. As an official offering from the city of Tokyo, 2,000 trees were uprooted from Japan and sent to the U.S. capital.

By 1910, Charles was working as a member of Patterson’s newly formed plant inspection team. Her job was to detect and identify fungal diseases on plants that were imported from abroad. When the first batch of cherry blossom trees arrived, she found that they were infested with numerous unknown fungi and insects. Charles noted “several kinds of pests, big bugs, little bugs and fungi, some of them unknown to this country and therefore extremely dangerous.” She isolated and described infested trees for later study. The specimens Charles collected from this group of trees still reside in the U.S. National Fungus Collections.

The trees sent from Tokyo were burned in 1910 at the request of the USDA to prevent further contamination. To avoid a diplomatic scandal, U.S. officials sent regrets to the Japanese people. When Japan sent 3,020 replacement trees two years later, they arrived in healthy condition and were planted along the Tidal Basin in D.C. Charles’s discovery of the infestation of the first shipment ultimately led to the Plant Quarantine Act of 1912. This Act authorized the USDA to inspect a wide range of agricultural products, including crops, livestock, and food. Charles’s research thus contributed not only to the expansion of plant pathology, but also to fundamental ideas of “native” and “non-native” species in the U.S.

Collaborative Research

Charles studied a wide range of commercial plants including pineapple, hemp, sweat pea, and rubber. She collaborated extensively with other researchers on several studies of plant diseases, and she wrote about the impacts of these diseases on public health, agriculture, and the U.S. economy in general.

Charles and Patterson jointly published research on the diseases of bamboo and sedge, for instance, as well as studies of other ornamental plants. Their papers detailed the signs of disease on host plants, the structure (or morphology) of the diseases themselves, and their economic significance. Their co-authored paper, “Pathological Notes Concerning a Few Ornamental Plants,” for example, discussed a fungal disease known as Botrytis. Characterized by a gray mold that affects many types of plants, they showed that Botrytis can ruin entire crops of strawberries, tomatoes, and grapes with disastrous financial consequences.

Even the papers that Charles wrote by herself show that collaboration was significant to her research. In her later career, she published a lengthy article in the Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences on a skin disease affecting muskrats. This 1940 paper, “A Ringworm Disease of Muskrats Transferable to Man,” describes a culture of fungus that was sent to the USDA by Dr. Paul L. Errington, a professor at Iowa State College who was conducting research on muskrats at the time. Dr. Errington had developed a skin disease on one arm, which he believed he had contracted through handling muskrat nests. Confirming this was the case, Charles’s paper demonstrated the importance of collaborative, interdisciplinary work and highlighted the possibility “of the transference of an animal parasite to man.”

But being part of the scientific community also meant challenging other researchers when necessary. This was often difficult for women of Charles’s generation who had less power in the profession. Her bravery shone through in a 1935 paper on “A Little Known Pecan Fungus.” In it, she challenged the way that a famous male mycologist, Charles Horton Peck, had identified and named a fungus affecting pecan leaves.

“Mobilizing the Benefits of Research”

In 1942, as the U.S. was entering World War II, the Chief of the Bureau of Plant Industry published a report emphasizing the role of plant science research in the American military effort. The contributions of Vera Charles, along with the work of four other women at the Bureau, were acknowledged for their dedication to protecting agricultural productivity during the War.

Charles’s expertise in plant pathology yielded descriptions of several new fungal species, advanced domestic food production, improved crop preservation, and supported international goodwill through agricultural exchange. Her career illuminates the decisive contributions women scientists at the USDA made to plant and human life in the U.S. during the early 1900s.

Glossary of Terms

Mycology

The scientific study of fungi, including their classification, genetics, biochemistry, disease properties, and practical use.

Great Depression

A period of global economic struggle from 1929 to 1939 that was characterized by unemployment, poverty, the collapse of banking institutions, and a reduction in international trade.

Further Reading

Bonta, Marcia Myers. Women in the Field: America’s Pioneering Women Naturalists. Texas A&M University Press, 1991.

Charles, Vera K. “A Ringworm Disease of Muskrats Transferable to Man.” Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 30, no. 8 (1940): 338–44.

Cash, Edith K. “Vera K. Charles.” Mycologia 47, no. 2 (1955): 263-65.

Malesky, Kee. “How D.C.’s Cherry Blossoms Almost Didn’t Bloom,” National Public Radio, March 26, 2011.

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.

You might also like

SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHIES

Mary Letitia Caldwell

Caldwell’s lab at Columbia University helped launch the careers of several women in U.S. biochemistry during the early 20th century.

DIGITAL COLLECTIONS

Food Science Collection

This digital collection features a broad spectrum of materials related to the production, packaging, and marketing of food.

DISTILLATIONS MAGAZINE

From the Front Line to the Freezer Aisle

How World War II changed the way we eat.