Annette Lykknes and Brigitte Van Tiggelen, eds. Women in Their Element: Selected Women’s Contributions to the Periodic System. World Scientific, 2019. 556 pp. $45.

Perhaps the most surprising twist in the 150-year history of the periodic table is its demotion to a pop-culture meme. Not only is the table now color enhanced and shrunk for reproduction on T-shirts and mugs, but its orderly rows and columns are often jokingly given over to other classes of objects, from species of fish to favorite brands of chocolate. As every chemist knows, these humorous uses ignore the genius of the table’s underlying schema—the way the elements take their place according to their characteristic differences, which vary from left to right in a repetitive pattern. The layout of the table, in addition to being a convenient way to pigeonhole the elements, holds the key to understanding their structure and behavior.

As a historical yet living matrix undergoing continual refinement, the periodic table opens itself to periodic reinterpretation. Editors Annette Lykknes and Brigitte Van Tiggelen have recently examined the table’s history and uncovered its feminine dimension. They planned their book, Women in Their Element: Selected Women’s Contributions to the Periodic System, to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the table. Their editorial point of view proves altogether interesting, instructive, insightful, and—in line with Mendeleev’s best intentions—predictive as well.

Women in Their Element pays equal attention to the well known and the largely unknown among its 47 subjects, allotting no more space to the towering figure of Marie Sklodowska Curie than to any other chemist. The book opens in the German town of Weimar in the early 1700s, with Dorothea Juliana Wallich’s experiments with cobalt; it extends into the present with the work of Dawn Shaughnessy, who leads a team at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California that has helped identify six superheavy elements, atomic numbers 113 through 118.

I confess that my initial look at the book’s table of contents left me appalled at the number of names I failed to recognize. As someone with a more than passing interest in the history of women in science, I could see at once Women in Their Element would prove revelatory. I know I will return to the book again and again to be reminded of who made which advance, and at what sacrifice, and with how much or how little support, recognition, or professional advancement.

The approaches of the 34 contributors to the edited volume added to my enjoyment because their contrasting styles highlighted differences in their subjects’ stories. These women were influenced by the cultural contexts in which they worked; they also had to cope with their particular era’s prejudices, from sex discrimination to Nazi persecution. Yet certain similarities among the women discussed become apparent as the reader moves through the chapters, so that the subjects almost sort themselves, like the elements of the periodic table, into groups and families. The most obvious category encompasses those whose discoveries filled in the blank spaces on Mendeleev’s table: Marie Curie, Berta Karlik, Lise Meitner, Ida Noddack, and Marguerite Perey. Then there are the women who headed chemistry departments or laboratories, including Ellen Gleditsch at the University of Norway and Ellen Swallow Richards at MIT; women whose names live on in the instruments they invented or the substances that honor their memory, such as Yvette Cauchois (the Cauchois spectrograph) and Kathleen Lonsdale (lonsdaleite); women who had enabling, encouraging fathers (Erika Cremer and Chien-Shiung Wu); women who married their lab partners (Irène Joliot-Curie and Dorothy Goddard); women whose careers were destroyed by marriage (Harriet Brooks and Clara Haber).

Two women I encountered for the first time in these pages, Jane Marcet and Margaret Todd, caught my attention for their way with scientific words. Marcet, born in 1769 to Swiss parents living in London, inhabited an international intellectual circle. She and her husband, Alexander, attended lectures by popular chemist Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution and would later repeat at home the experiments they had seen Davy perform. She became so well informed about the latest chemical developments she decided to share her knowledge with the public and did so in the form of a published dialogue between an older woman and two teenaged girls. Marcet’s Conversations in Chemistry first appeared in 1806, anonymously. Its popularity in the United Kingdom and the United States, as well as in France, Germany, and Italy, spurred the author to issue new editions over the next 50 years. When Davy began discovering elements through electrolysis in 1807, Marcet was quick to report his progress. Of the 25 elements that came to light during her publishing career, 20 were discovered by people she knew. She exerted an incalculable positive influence on a wide audience. Michael Faraday, for example, read Conversations in 1810 while still a bookbinder’s apprentice, and he credited the book with awakening his interest in science.

In contrast to Marcet, Margaret Todd contributed only a single word to the scientific literature, but it was the perfect word for an as-yet-unnamed and ultra-important entity. The word popped up at a dinner party held in Glasgow in 1913, though unfortunately none there recorded the exact date. Todd, who had been one of the first to attend the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women when it opened in 1886 and who had only just returned to Scotland after living in England for several years, was the guest that night of the prominent industrial chemist George Beilby and his wife, Emma. Their daughter, Winifred, was also present, along with her husband, Frederick Soddy, who had worked with Ernest Rutherford at McGill University in Montreal. There the two had demonstrated that radioactive elements decay into other elements. Dinner conversation at the Beilbys’ naturally turned to more recent questions in radiochemistry, specifically to the 35 radioactive disintegration products that refused to fit into the available spaces on the periodic table. These were not new elements per se but new versions of existing elements that differed from their cognates in only one regard, their atomic weight. Soddy had been calling these misfits “radio elements chemically non-separable,” but it made for a clumsy mouthful. Todd, who had studied Greek as an undergraduate and wrote novels in addition to practicing medicine, considered the nomenclature problem: these same-but-not-the-same elements deserved to share the name of their chemically identical sibling and to stand with them in the same places on the periodic table. The Greek words isos topos came to her, meaning same place. “Isotope,” she suggested, and Soddy adopted it immediately. Isotope appeared in his published papers that same year, and in 1921, when he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, his citation made mention of “his investigations into the origin and nature of isotopes.” Today the building that was once the Beilby residence bears a plaque certifying its distinction as the site of the dinner party that birthed the word.

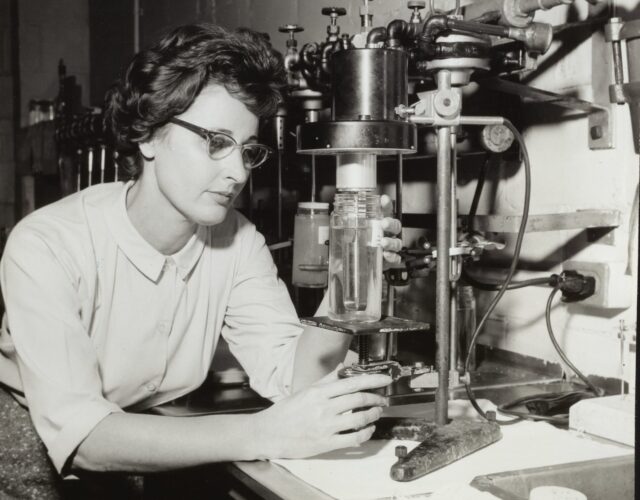

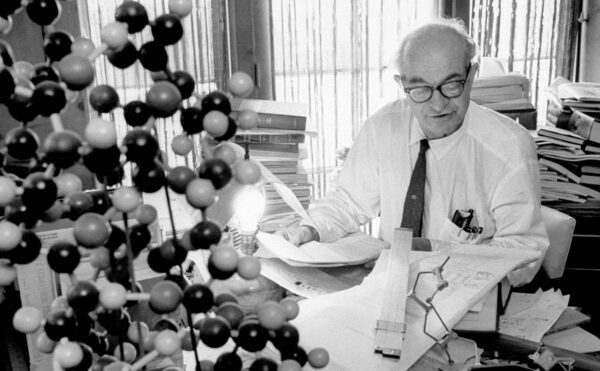

Women in Their Element includes a family album’s worth of photographs. Many are studio portraits or solo snapshots of individual chemists, but others capture the women at work with their colleagues, both male and female. My favorite is the one chosen for the cover, showing members of the Wilson College Chemistry Club, circa 1937—a gaggle of coeds clustered around a balance and a rack of test tubes, with a wall of laboratory glassware and a pull-down chart of the periodic table at their backs. A group of girls interested in science, the picture seems to say. What could be more natural than that?

Readers will come away from the book awakened to the presence of many more women in many more labs than they’d ever suspected, and there’s the added sense that other women, as yet unidentified, were also there. The word selected in the book’s subtitle strengthens the impression that we have not yet heard all the pertinent names or learned all the contributions that women have made in this arena.

Given that the number of women recognized as chemists increases as a function of time in the pages of Women in Their Element, from two in the 18th century to some two dozen in the 20th century, I suspect a revised edition would likely contain many more of these engaging and inspiring stories. I look forward to reading them.