The Wellness Warrior

In 2008, at age 22, Jessica Ainscough was diagnosed with a rare, soft-tissue cancer called epithelioid sarcoma in her left arm. Her doctors recommended a forequarter amputation, a traumatic procedure that removes the arm and shoulder, arguing that this offered her the best chance of survival. Young and optimistic, Jess balked at the idea of such a radical operation and tried a high-intensity chemotherapy treatment instead. After a brief remission, the cancer returned in 2009. Her doctors again recommended amputation.

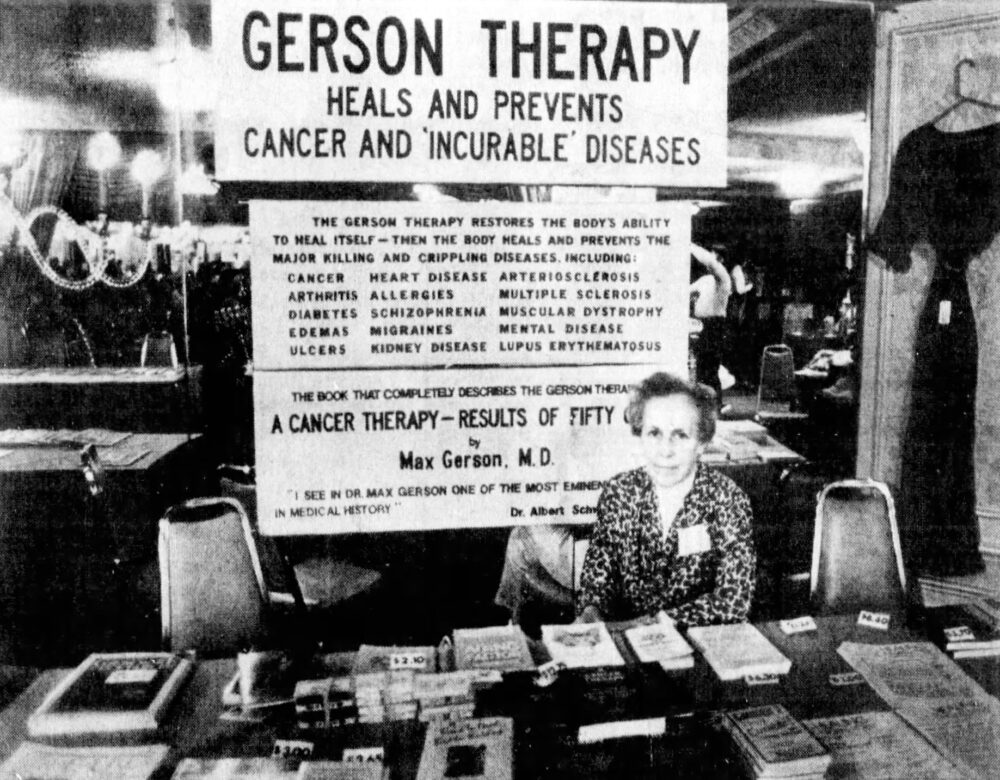

This time, Jess looked further afield for a solution. She found an unproven but long-standing regimen known as Gerson therapy, which prescribes daily enemas using coffee, a mass of dietary supplements, and a strict, organic vegetarian diet. She documented her experience on a blog, attracting an audience of thousands as Australia’s “wellness warrior.”

“I am ecstatic to report that it has worked for me,” she announced in a 2012 column for Dolly, a teen magazine she worked for at the time of her diagnosis. “I have had no cancer spread, no more lumps pop up (they were popping up rapidly before) and I can actually see some of my tumours coming out through my skin and disappearing.”

That year Jess celebrated two years of “intense detoxification and nutritional treatment” through Gerson therapy. “I’m not sure if I will ever be ‘cured,’ but I will always be healing,” she wrote. “Cancer is something I will always manage with my clean lifestyle.”

She calculated in a blog post that she had consumed

2,920 coffee enemas

1,460 baked potatoes

1,460 bowls of Hippocrates soup (a type of vegetable soup)

33,580 supplements

174 shots of castor oil

When her mother, Sharyn, was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2011, Jess convinced her to follow the Gerson therapy as well. It didn’t work. Sharyn passed away in 2013. In 2015, Jess’s blog posts slowed. She died that year, aged just 29.

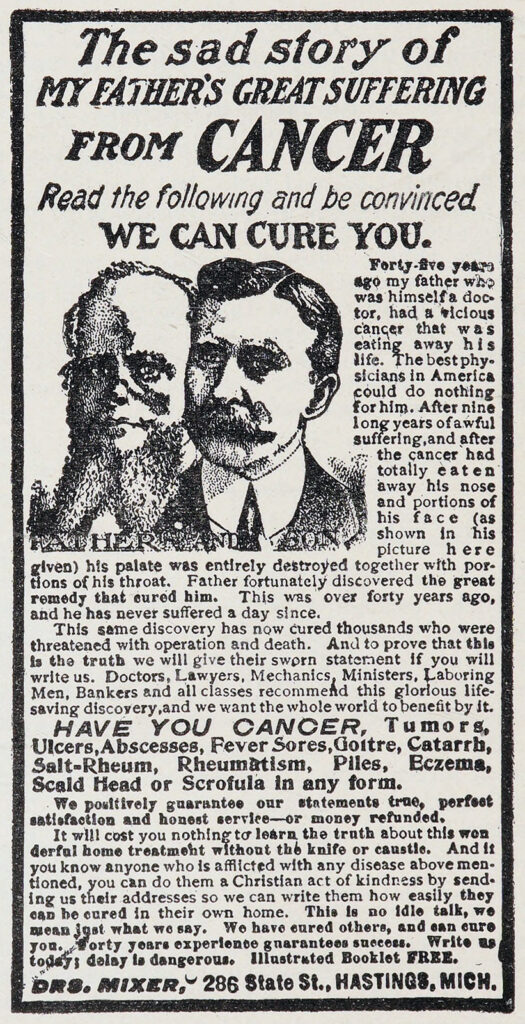

Jess was not alone in seeking alternatives to mainstream cancer treatments. In fact, a panoply of alternative therapies has grown so associated with cancer treatment they have been incorporated into orthodox practice with the development of so-called integrative oncology, in which hypnosis, herbal remedies, and acupuncture aim to alleviate suffering and complement first-line treatments such as chemotherapy and surgery. In the United States, approximately 79% of cancer survivors report using supplements, alternative, or complementary treatments.

But the line between complementary therapy and quackery can be a blurry one, and the disease is still dogged by conspiracy theories. What is it about cancer and its care that renders it so vulnerable to medical skepticism? Is it something specific to the disease itself? Why are other conditions—ones that also cause protracted suffering and death—not plagued by quackery in quite the same way? Is the answer to be found somewhere in cancer’s history?

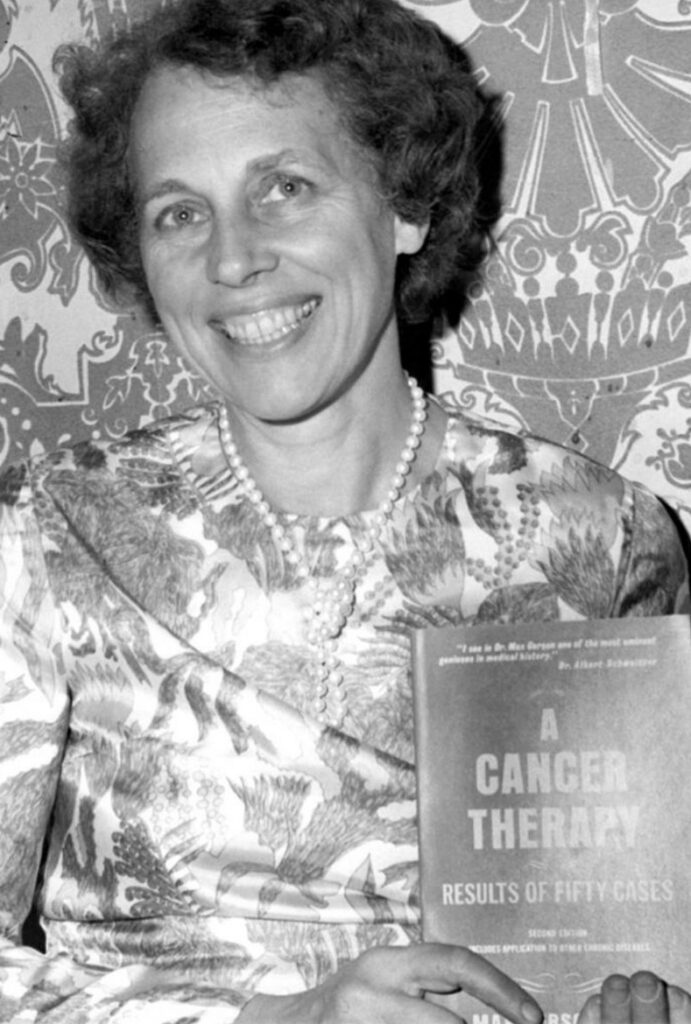

Max Gerson and His Therapy

In 1958, Max Gerson published a book in which he claimed to have cured 50 previously terminal patients as an oncologist at Gotham Hospital. The book’s purpose was simple, the 77-year-old Gerson wrote—to prove “there is an effective treatment of cancer, even in advanced cases.” An editor’s note appended to the third edition of A Cancer Therapy: Results of Fifty Cases, published in 1977, claimed that “many of the ‘terminal’ cancer patients treated by Dr. Gerson . . . are still living normal lives free of cancer.”

For example, Case No. 1 presented a 44-year-old married mother of two from New York, who had been diagnosed with an exceptionally large tumor of the pituitary gland. She had lost much of the vision in both eyes, and the surrounding bones had been eroded by the cancer’s progress. She had received some X-ray treatments at Mount Sinai Hospital but had refused an operation. She had lost a lot of weight and lapsed in and out of consciousness. Her family took her to Gerson at Gotham Hospital in an ambulance. He started treatment immediately, the book reports: “teaspoon by teaspoon, day and night, she was induced to take these juices.” She regained full consciousness after just a week. At the end of two months, the patient was “feeling fine and able to do her own housework.” In 1977, she remained “in good health and working power.”

Case No. 29 involved a woman with breast cancer. When Gerson first met her in 1952, she complained of “very intensive pain” in her back, arms, and shoulders. She was “extraordinarily nervous” and had even penned her “own death sermon.” After six months of Gerson’s treatment, she was “restored to full working power; free of pain.”

All 50 cases in A Cancer Therapy end like this—a miraculous recovery; a full restoration of life, leisure, and labor.

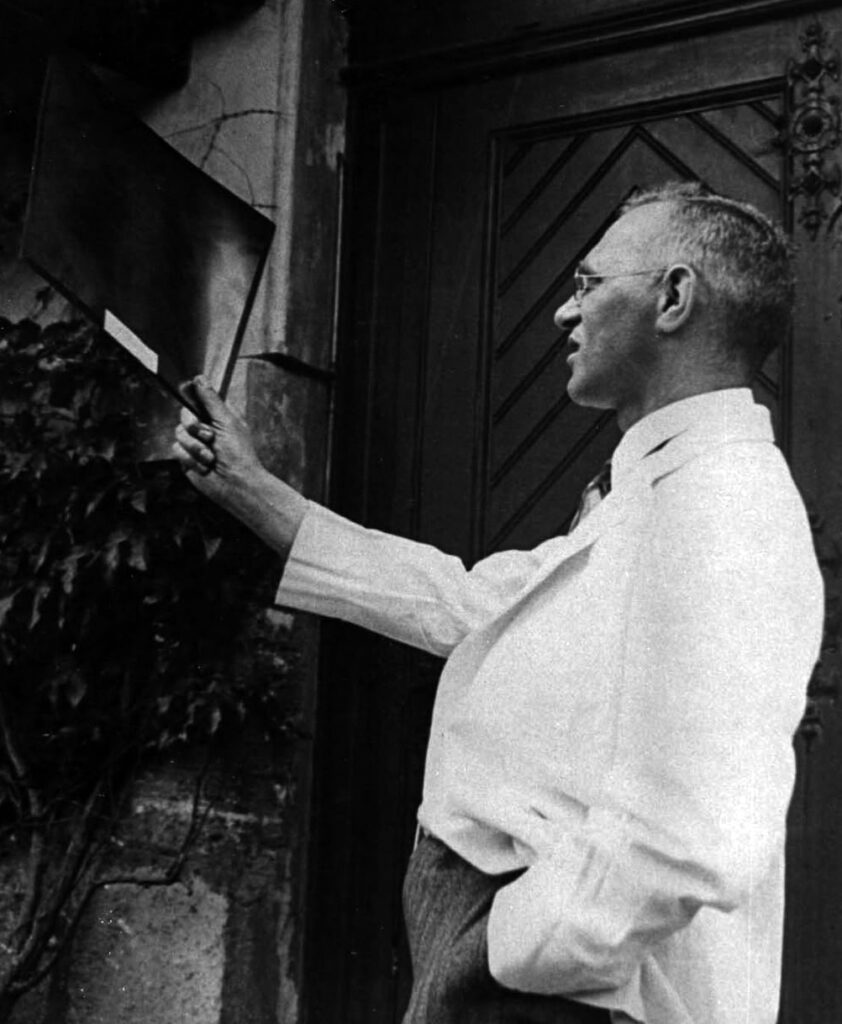

Gerson was born in 1881 to a Jewish family in present-day Poland. He graduated from medical school in 1909 and began to practice medicine in what is now Poland and Germany, where he first developed his dietary therapy. Starting first with the treatment of tuberculosis of the skin in the early 1920s, he began to apply the diet to cancer patients in 1928. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, he left Germany for Vienna, where he continued to treat cancer patients, before moving to France in 1935, London in 1936, and finally settling in 1938 in New York, where he opened a private clinic on Park Avenue.

Gerson’s theories were relatively simple. As he wrote in a letter to his daughter, “stay close to nature, and its eternal laws will protect you.” He believed that if the body was in its natural, healthy state, then cancer was curable. Rather than intervening in or interrupting the body’s natural processes, his therapy restored its inherent “ability to heal cancer.”

Cancer was susceptible to such “natural” healing gifts, Gerson argued, because it was—unlike infections—of the body. Cancer was caused by a normal physiological process going awry and so, the logic followed, a cure simply required persuading the body back to normality. He cited the view of prominent biochemist Jesse Greenstein that “cancer is a phenomenon coexistent with the living process.” It was, in other words, part of nature and so could be corrected by nature.

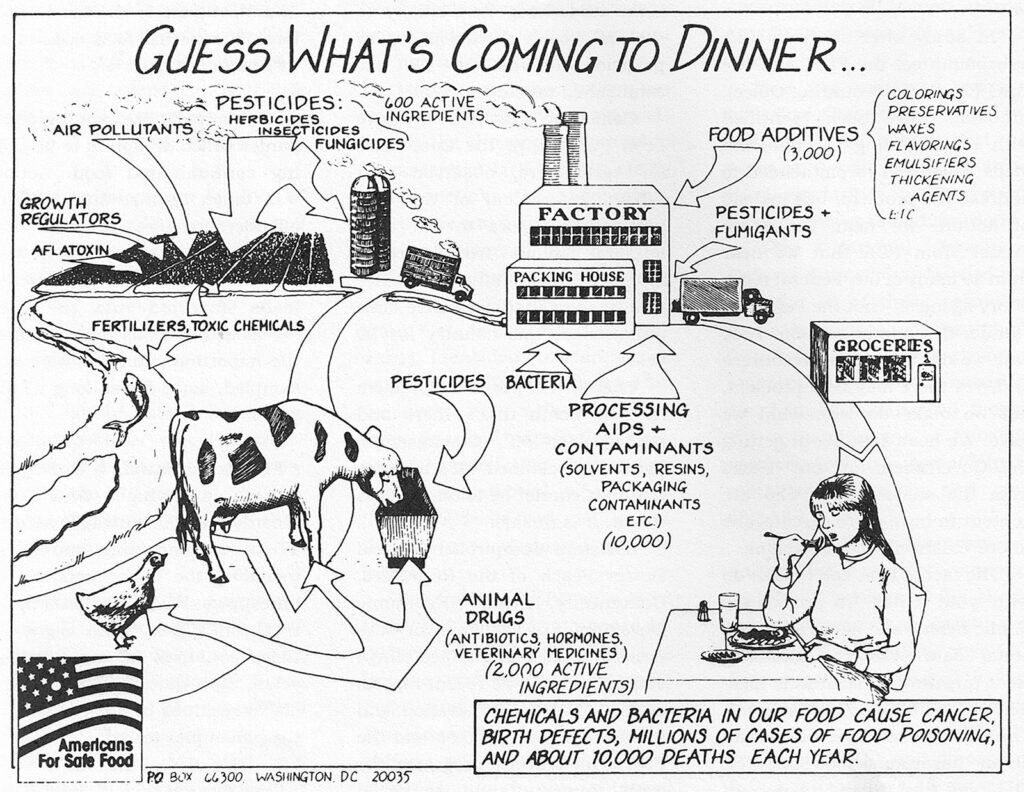

Gerson’s commitment to the powers of nature went beyond the body. He believed that cancer was on the rise because we had not been treating the world well. “I fear,” he wrote, “that it will not be possible . . . to repair all the damage that modern agriculture and civilization have brought to our lives.” The harm wrought by “modern civilization” began, he argued, “with the soil.” He advocated for “natural and unrefined” foods, such as organic fruit and vegetables, as both treatment and prevention.

While in some ways his environmentalism was prescient, he was also operating within a broader intellectual milieu. In the 1920s and 1930s, people such as the Austrian occultist, educationalist, and social reformer Rudolf Steiner, English botanist Albert Howard, and farmer Lady Eve Balfour pioneered systems of organic agriculture in response to the perceived deterioration of the health and quality of soil, crops, and animals resulting from chemical fertilizers.

Gerson was also drawing on a long tradition of understanding cancer as a product of civilization. He was one of many who believed that an apparent increase in the prevalence of cancer during the 20th century was a product of the altered diets, lifestyles, and environments that accompanied modern industrial life. He argued, as did many Western researchers, that various communities in Asia, Africa, and South America were cancer-free, whereas white people’s “civilized” culture was carcinogenic.

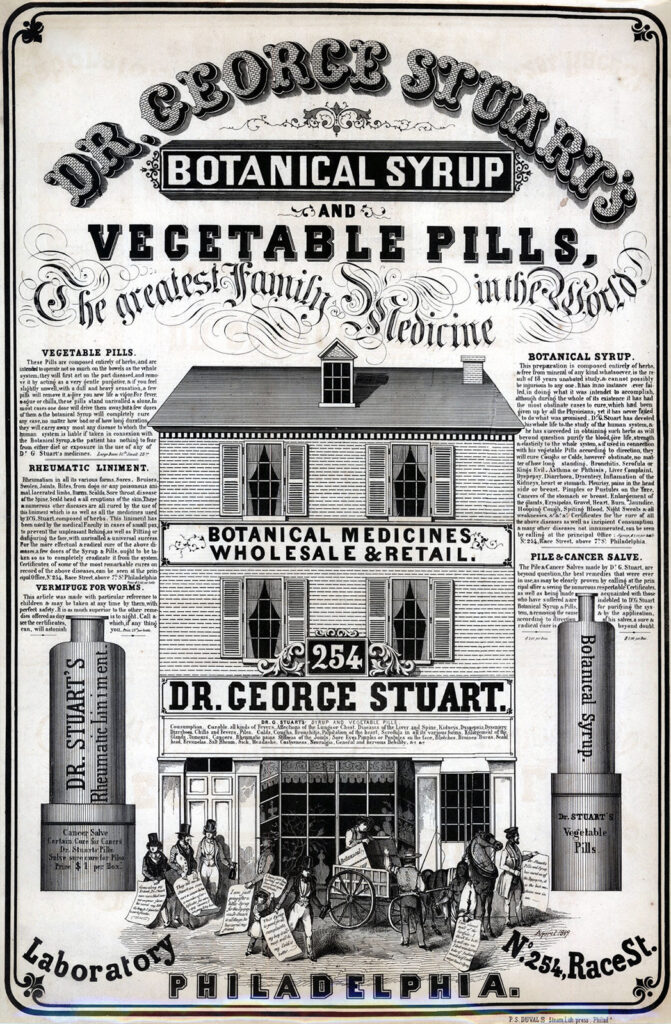

While these ideas were widespread at the beginning of the 20th century, many of Gerson’s colleagues were unconvinced by his therapy, finding his methods and claims dubious at best, harmful at worst. In 1953, Gerson’s malpractice insurance was discontinued, and in 1958 his medical license was suspended. Unsurprisingly, then, his writings adopt a resentful tone.

The second edition of A Cancer Therapy was dedicated “to the doctor who really wants to heal” and “to the patient who really wants to be healed.” He painted a portrait of medicine as a deeply conservative and risk-averse profession. “Very few physicians like to change their medical approaches,” he wrote. “The majority practice what they have learned and apply the treatments of the textbooks more or less automatically.” Gerson saw himself as an embattled outsider, struggling to convince the mainstream to take a chance to save lives.

Gerson died of pneumonia in 1959, the year after publishing A Cancer Therapy. Conspiracy theories around his life, work, and death emerged almost immediately. His supporters believe the medical establishment prevented him from publishing proof his therapy worked; some even claim he was murdered by his clinical rivals. One biographer described Gerson in the 1990s as “the strangest, most frustrating story of my life . . . the story of a man who by absolute record had cured people of cancer, including children, and his incredibly courageous and lonely fight against the forces of organized medicine.”

Gerson’s Afterlives

After Gerson’s death, his daughter Charlotte continued to promote his therapy, founding the Gerson Institute in 1978. The institute still exists, running two residential clinics out of Tijuana, Mexico, and Budapest, Hungary. For the past 40 years it has been, according to its website, “the leading global source of information, licensing, training, and patient support for treating the underlying causes of disease: toxicity and nutritional deficiency.” The organization claims to have “helped thousands of patients recover from chronic degenerative diseases.” These patients are “living testaments to the power of food as medicine.” It promotes the “internationally recognized treatment system” with four major pillars: “diet, juices, detoxification, and supplements.”

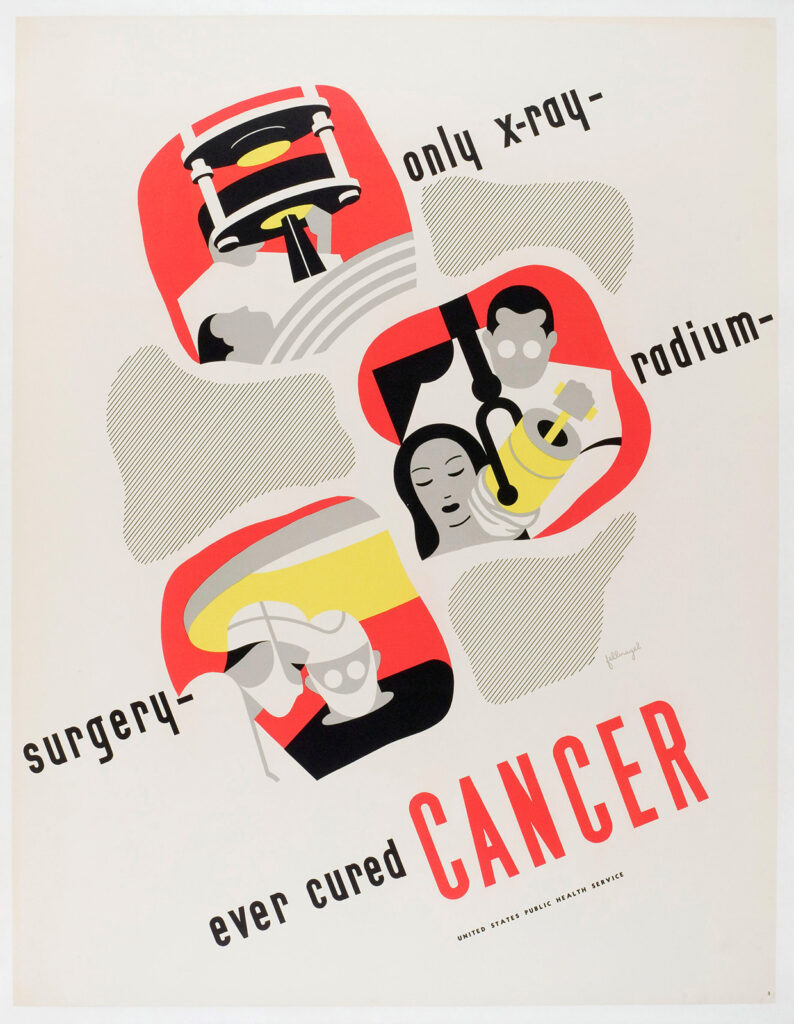

In the 1950s, mainstream doctors were able to offer relatively little to their cancer patients. While from the 19th century onward surgery and radiotherapy could at least palliate suffering, effective, curative treatment remained elusive. Against this backdrop and during his lifetime, Gerson’s appeal makes some sense.

But since then, cancer treatments have become more effective and more humane. New chemotherapies, immunotherapies, and surgical techniques have emerged and, mostly, have improved life expectancy. Why then was Jessica Ainscough skeptical of the treatment options her doctors offered? Why did she, and millions like her, seek alternatives despite the proliferation of more effective and humane mainstream therapies? Indeed, cancer quackery shows no sign of abating. In the United States, cancer survivors spend an estimated $6.7 billion annually on alternatives and complementary remedies.

Ainscough was an early “wellness influencer,” responsible for presenting Gerson’s treatment as a viable, effective alternative to her followers. Influencers can seem relatable and empathetic, and desperate people seeking connection as much as cures are vulnerable to the community social media offers. These networks allow grifters to build audiences of millions, and charlatans peddling miracle diets or supplements through them are difficult to identify, trace, or debunk.

But it’s trite to blame alternative therapies’ persistence on the rise of social media alone. Gerson, after all, didn’t have a TikTok account.

In 1957, George W. Crile, a physician and one of the founders of the American College of Surgeons, lamented that society had “fashioned a devil out of cancer.” We had created a new disease, he insisted, a contagion that traveled “from mouth to ear.” He called this new malady “cancerphobia.” People feared cancer, but they also feared conventional cancer treatments. The pain and suffering caused by malignancy was matched and sometimes exceeded by the harm levied by the therapies available to 1950s doctors. And even the most effective treatments might only buy a patient a few more months of healthy, happy life. Fear, then, propelled men and women into radical, alternative, and untested treatments, including Gerson’s regimen.

Cancer treatment has changed radically since the 1950s, but its reputation lags. And chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery—which remain the frontline treatments for the vast majority of patients—can still have terrible side effects and long-term health consequences.

“The way I saw it I had two choices,” Ainscough wrote in Dolly. “I could let them chase the disease around my body until there was nothing left of me to cut, zap, or poison; or I could take responsibility for my illness and bring my body to optimum health so that it can heal itself. For me it was an easy decision.”

Uncertainty also abounds in oncology. This is, of course, true for science and medicine more generally, but there is something not only in cancer’s complexity and in the vast array of illnesses, prognoses, and experiences collected under the cancer umbrella, but in the elusiveness of the eradication of the disease, even in the best possible circumstances. After all, most cancer doctors will speak in terms of probabilities, remission rates, and years gained. Gerson, by contrast, spoke in absolutes. He and those of his ilk promise patients a complete cure.

This uncertainty—the inability of conventional doctors to offer absolutes—is a challenge to mainstream medicine, oncologist Dr. Stacy Wentworth suggests. Patients are more likely to consider alternative treatments whenever doctors say, “we don’t know what caused this, or we’re not sure what treatment is going to be best for you.”

The uncertainty of medicine, and the appeal of alternatives, has, perhaps paradoxically, increased as screening and diagnostics have improved and as cancers are caught earlier and earlier. For the patient, an unappealing invasive treatment is made even less so if it’s for something that’s asymptomatic and causing them little to no trouble.

“We kind of have to sell cancer treatment a little more to them,” said Dr. Wentworth. While screening might have brought about improvements in survival, there does seem to be a cost. In the widening gulf between diagnosis and either cure or death, more space has been made for quackery to thrive.

Why are other conditions—ones that also cause protracted suffering and death—not plagued by quackery in quite the same way? Is it just that cancer, as Crile argued, has been made into a superlative disease, feared in ways other sicknesses are not?

Gerson suggested there is something in cancer’s etiology, its cause, that makes it unique. Cancer doesn’t invade from without—it is of the body. If the body made cancer, surely it can unmake it.

“Our bodies are designed to heal themselves,” Ainscough wrote in a 2010 editorial for Australian public broadcaster ABC News. “It is really that simple. Our bodies don’t want to die. The environment we subject them to and the food we feed them determines whether they will flourish or flounder. This is the basis of natural cancer-fighting regimes.”

This belief in the power of the unimpeded body and its capacity to cure disease chimes with a wider cultural commitment to nature—a commitment that has been around for centuries, and is now being even more robustly embedded into American society via the appointment of people such as vaccine opponent Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and celebrity quack peddler Mehmet Oz to lead the country’s healthcare agencies.

It was this relationship between nature and cure that seemed to first draw Ainscough to Gerson’s therapy. Indeed, it is how the treatment is marketed to millions. But Gerson’s own motivations—and those of other alternative practitioners—remain more elusive. Did Gerson believe in the validity of his treatments, or was he simply a charlatan, exploiting vulnerable people for financial gain and professional accolades?

We can only speculate. Dr. Wentworth offers two possible interpretations, both to do with the personality of doctors. It takes a “very specific kind of person” to become a doctor, she says. There is a “component of narcissism” and a “need for power” threaded through the medical profession. Perhaps this is especially true among those who turn away from conventional practices. Alternative treatments, especially ones that promise cures for incurable illnesses, allow their practitioners to wield superlative power—they can offer what no one else can.

Her other interpretation is more generous.

“Helping another human being is one of the greatest joys of being an oncologist. . . . To say, ‘I have something to help you’ is a rush that’s like delivering a baby. It’s the most amazing thing,” she says. By contrast, “telling them you can’t help is one of the hardest conversations. . . . That means a patient is going to die. . . . And to say that to another human being is very difficult.”

Was Gerson just chasing that high? Or was he unable to disappoint, unable to have the hard conversations that medicine requires?

Surely there is more to the pull of cancer quackery than personality flaws. To attribute it as such—or to reduce it to opportunists exploiting gullible fools—is to ignore a valuable alert system. Ainscough might have been lured by charismatic peddlers with persuasive promises, but she was also dissatisfied by what her doctors had to give.

Cancer quackery may be exploitative and even cruel, but it is also a manifestation of the limits to what clinical science and current pharmaceuticals can actually offer people. Where medicine fails, quackery thrives. There is no clearer indicator of the flaws in our current system, no better place to look for where and how to make improvements.