The tourists are almost all smiling. Some wrap arms around companions or young children; others stand tall and give a thumbs-up. Members of an orchestra pose stiffly in matching blue neckties; a dozen retirees in white socks and tennis shoes beam for the camera. Most pose in front of a five-story wall of neatly stacked aluminum tubes. One Facebook poster jokes that it looks like the world’s largest wine rack. Another post prompts a friend to ask, “What is this, Wall Street?”

The scene could be playing out anywhere in the United States or in the world, really. You could swap in a backdrop of the Eiffel Tower or the Magic Kingdom without changing much else. But the sightseers in these photos have chosen a more unusual destination. This is where the nuclear age began, a few minutes before midnight on September 26, 1944. It is the Hanford B Reactor, where men and women of the Manhattan Project worked in secret to produce the plutonium used in the world’s first atomic weapons.

Today the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, situated along the Columbia River in a remote area of southern Washington State, is part of the country’s national park system. The aging buildings of this once sprawling compound have been decontaminated and stamped with the National Park Service’s iconic arrowhead logo. The park’s museum lets youngsters pose with child-sized mannequins of nuclear physicists Enrico Fermi, the first person to demonstrate a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, and Leona Woods, who helped supervise the construction of Hanford’s reactors. Further on, tourists can sit at the control station where engineers monitored the transmutation of uranium into plutonium; now these instruments are props for silly photos of mischievous-looking teens with their hands poised over ominous-looking buttons.

Retired reactor workers guide visitors through rooms decorated with rusting wall clocks and World War II–era propaganda posters. One depicts a small girl clutching a photograph of her father in military uniform and reads, “What you’re making may save my Daddy’s life.” Another features a hard-hatted worker waving goodbye to his daughters in the morning; the caption reads, “Protection for All: Don’t Talk. Silence Means Security.”

The retired workers, many in their 70s or 80s, are free to talk today. Inside their former offices and break rooms they take time to discuss the work they once did and explain the science of a nuclear reaction.

Still, the Hanford Nuclear Reservation is a work in progress. Even after decades cleanup of the sprawling compound continues. Many buildings are still being demolished, and radiation leaks periodically force workers to take shelter, as happened in May 2017 when a tunnel used to store radioactive waste collapsed. (In response, the Federal Aviation Administration temporarily restricted flights over the area.) Radioactive materials persist in the soil and groundwater, and leftover waste from the reactor trickles from leaky underground tanks. Because of these risks families with young children must sign a release form acknowledging such hazards before they enter the site.

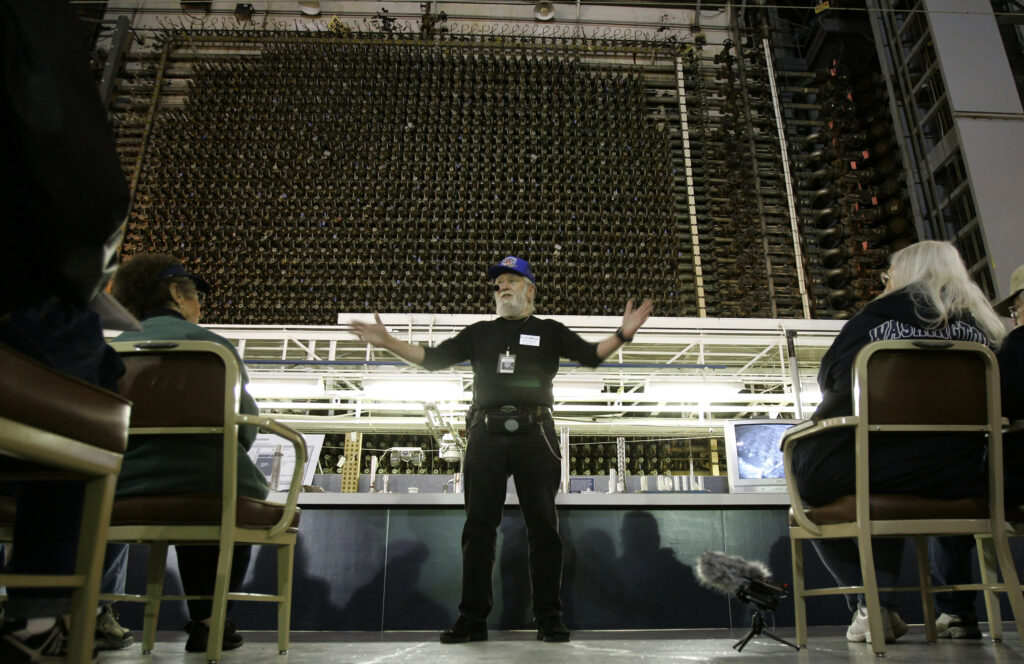

Historian Burt Pierard addresses a tour group at the Hanford B Reactor, 2008. The reactor made the plutonium for the Trinity Test and the bomb that destroyed Nagasaki.

About 80,000 people have visited the park since it opened for tours in 2009, according to the Department of Energy. Tourists have brought about $2 million annually to the nearby city of Richland, says Colleen French, program manager for the park at Hanford. From the outset tourism has been a driving force behind the conversion from radioactive ruin to museum. The B Reactor Museum Association describes it as a “unique educational venue” and “a cornerstone for Heritage Tourism in the Pacific Northwest.” But why would someone choose an old nuclear plant for a family vacation?

“There’s a certain kind of macabre fascination with these places,” says Linda Richards, a historian of science at Oregon State University who has studied the Hanford museum. “I think it also ties in with this kind of lighthearted sense: it’s retro, it’s hip, it’s not dangerous anymore. It’s normalized.”

Museum visitors describe their experiences in generally positive terms, using words like “memorable,” “historic,” and “eye-opening.” Some say they find the experience sobering yet illuminating. “Morbidly, it felt a bit like standing in a cathedral,” Heather Young, who visited in fall 2016, wrote on the travel site Trip-Advisor. Another visitor felt “complete awe.”

Curious travelers are having the same sort of experiences around the world. Snapshots of visits to other Manhattan Project park sites and even to Ukraine’s Chernobyl exclusion zone—the site of the disastrous 1986 reactor meltdown—show people happily handling artifacts and grinning by memorial plaques. Through tourism, it appears, atomic history has become a lark, and the nuclear age has been made entertainment.

The wall of rods in the Hanford B Reactor that now attracts vacationers was once a place of creation, where uranium was torn apart and remade as plutonium.

That process began with a beam of neutrons streamed into the reactor’s graphite core, which slowed the neutrons down. Their idle pace allowed the nucleus of a uranium-238 atom to absorb a neutron, momentarily forming uranium-239 before the extra particle wrenched the nucleus apart. The splintered atom spewed heat, gamma rays, and three more neutrons. Those extra neutrons bounced off the graphite, too, which slowed them down so they could also be absorbed and could split more atoms. This all happened in less than an instant, triggering a chain reaction.

The resulting flood of neutrons joined up with countless other atoms. After about 23 minutes half of the uranium-239 had transformed into neptunium, another unstable element. About two days later half the neptunium had transformed into a few grams of plutonium, which was refined using hydrochloric acid and then purified into plutonium metal. Plutonium is very stable and will persist for hundreds of thousands of years if untouched. But it, too, can be split apart. The element named for the underworld can become death, a destroyer of worlds.

Within the Hanford B Reactor the transmutation unfolded silently, slowly. There were no moving parts save for the movement of atoms through the void. The only sound was the rushing of the Columbia River, whose waters were diverted into the reactor to cool it, at the rate of 75,000 gallons per minute. Engineers and physicists monitored the reactor from nearby stations and controlled the process that began the nuclear chain reaction. But once the reaction began, it was self-sustaining, only requiring the addition of fuel and, when spent, its removal.

On December 26, 1944, workers on contract with DuPont processed the first small batch of plutonium nitrate at the Hanford site. Colonel Franklin Matthias, the officer in charge of Hanford, personally took the purified plutonium on the first leg of its journey to Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. On July 16, 1945, Los Alamos scientists detonated a bomb with this plutonium at its core. The successful Trinity test was the world’s first nuclear explosion and the capstone of the Manhattan Project.

Meanwhile, the Hanford B Reactor continued to produce plutonium. Throughout the spring and summer of 1945 more plutonium slugs were shipped from Washington to Kirtland Air Force Base, south of Albuquerque. From there, on July 28, a plutonium core made in Hanford was flown to Tinian, one of the Northern Mariana Islands, and assembled into a blimp-shaped bomb called Fat Man, which was loaded onto the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Bockscar.

Bockscar lifted off at 3:47 a.m., August 9, 1945, and made its way over Japan. The country was already reeling. Three days earlier the Enola Gay had dropped a similar bomb, but one made from uranium, over Hiroshima; the bomb, called Little Boy, killed an estimated 66,000 people. At 11:02 a.m. local time, August 9, Bockscar’s bombardier dropped Fat Man through a hole in the clouds, and it plummeted toward the city of Nagasaki. After a 43-second free fall a charge within the bomb detonated, starting a series of shock waves that crushed the plutonium core. This released a fountain of neutrons, which began to split the plutonium atoms and release more neutrons in the same manner as the reaction that produced the plutonium in the first place. Atoms came apart. The heat and radiation unleashed by these splitting atoms was equivalent to 21 kilotons of TNT.

An estimated 40,000 Japanese people died instantly, and at least another 40,000 would succumb to immediate and long-term health effects. The atomic bombs are generally credited with ending World War II and heralding a new era of both war and peace.

After the war the B Reactor kept producing plutonium. It supplied most of the fissile material for the tens of thousands of nuclear bombs the United States built throughout the Cold War before the reactor was shut down in February 1968 and subsequently decommissioned. From 1969 through 2006 workers dismantled and removed more than 50 buildings and service facilities, sparing the reactor building, exhaust column, and river pump house. As recently as 2008, cleanup plans called for removing those, too, but that year the facilities became a National Historic Landmark. President Obama designated it part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park in 2014.

Hanford had a life before the bomb. Until the government relocated residents, the site had included two small agricultural towns, Hanford and White Bluffs, as well as a Native American community that predated white settlement by centuries. Residents of those towns and the Wanapum tribe were given 90 days or less to evacuate their homes to make way for the hush-hush federal project. The 586-square-mile area encompassed lands used by several tribes, including the Cayuse, Umatilla, Walla Walla, Yakama, Colville, and Nez Perce, who had hunted and fished in the area for at least 10,000 years. All were removed and denied access to the land. Today, the concrete husk of Hanford High School is one of the few pre−Manhattan Project relics that remain. Don Young, an army veteran who visited Hanford in August 2016, says he didn’t learn much about this history from the museum, instead finding it in a book.

“I expected a fuller contextual discussion of the World War II effort. While the site does describe the displacement of the farmers who were in the area before the war, the materials were near silent on how the Hanford site was selected—that it was close to hydroelectricity, lots of water, and in the middle of nowhere,” he says.

The tour also does not mention the thousands of people who were sickened by radiation during the reactor’s production days. Some visitors, who have either learned of these ill effects themselves or know the area’s history, point out these omissions in their reviews across social media. “The only downside I noticed was the unawareness of the [tour guide] workers themselves of the massive radioactive contamination that the operation … generated, either via liquid waste or gas,” writes one TripAdvisor user who visited Hanford in April 2017.

As part of plutonium production and refining, the plant released radioactive iodine into the air, and it drifted onto pastures where cows grazed. Children who drank milk from those cows were at risk for developing thyroid disease because radioactive iodine concentrates in that gland. In 1990 thousands of residents, many suffering from thyroid conditions, including thyroid cancer or hypothyroidism, sued federal contractors, according to the Tri-City Herald. The Department of Energy indemnified the contractors, which included DuPont, General Electric, and Rockwell International, meaning the federal government was responsible for legal costs. The final cases were resolved in October 2015; the Department of Energy, which was legally obligated to defend the contractors, paid more than $60 million in legal fees as well as $7 million in damages.

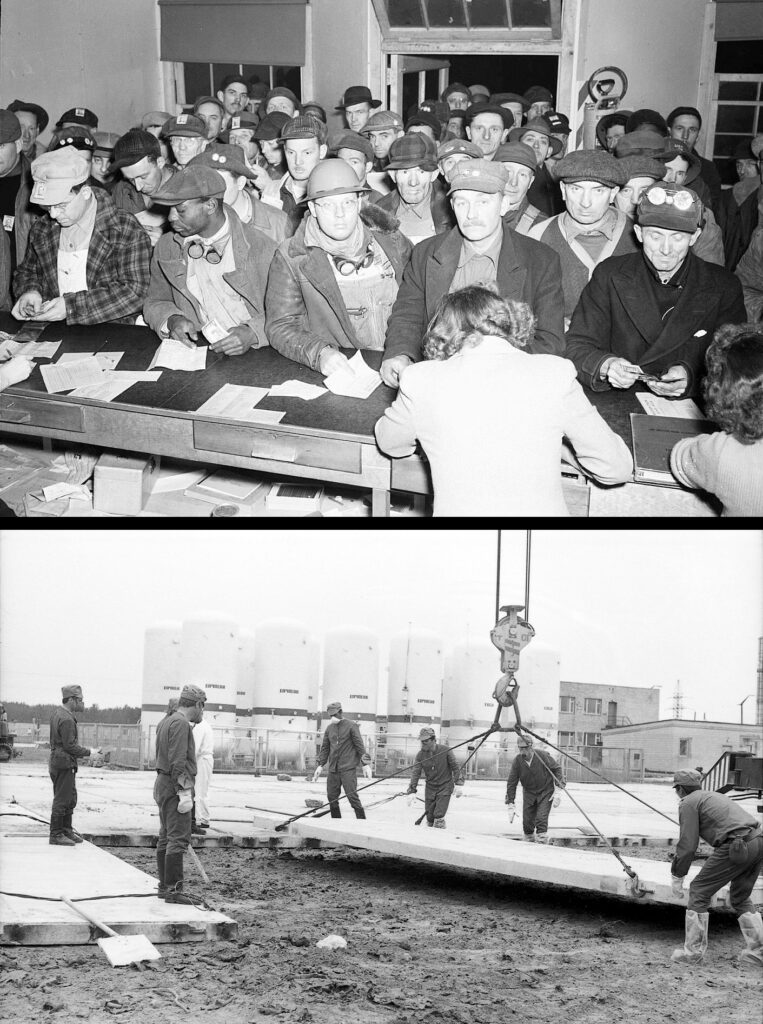

Above, Hanford workers waiting for paychecks at the Western Union office, undated. Below, Soviet soldiers, known as liquidators, assist with the cleanup after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, May 1986. Later in life both groups of workers developed health problems, especially thyroid and brain cancer, related to radiation exposure.

Trisha Pritikin, who grew up in nearby Richland, appreciates the scientific achievement the reactor represents and says its history is worth sharing. She is also cofounder of an advocacy group called Consequences of Radiation Exposure (CORE). Her father was an engineer at the plant, and he died of aggressive thyroid cancer. Her mother died from a malignant form of melanoma, Pritikin says. She had her own thyroid removed at the earliest sign of symptoms. At the very least she believes the park’s history should include the story of these people.

Pritikin says she understands why the bomb was built amid fears of a German nuclear weapon. “But that does not mean we can’t talk about the health consequences,” she says. “We should be able to talk about both.”

The National Park Service and the Department of Energy, which co-manage the site and tours, are more invested in portraying the legacy of the technology itself and the marvels engineers accomplished before the age of computers.

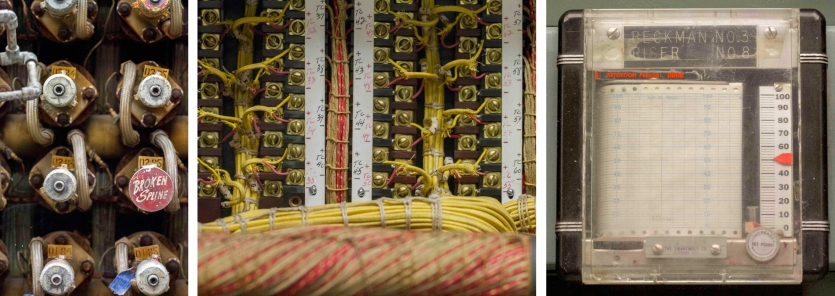

“What was most interesting to me was the complicated, yet art-fully and meticulously crafted wiring and control features, including, for example, an emergency shutdown mechanism powered by silos of gravel,” says museum visitor Justin Jaesch, who grew up in southern Washington and visited the museum in 2016.

Not all visitors feel this way. “I found the on-site stuff narrowly focused on the production of plutonium, with no or just a sideways reference to what the plutonium was used for—whether in World War II or during, and now after, the Cold War,” says Don Young, the army veteran who visited in August 2016.

Richards says that the museum tour elides that history and the story of contamination at the site. “As it is now, the site is not a place to contemplate the results of the B Reactor but a place where we are to be astonished by technology,” she says.

The National Park Service mission, to “preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources,” means the visitor experience of Hanford is agnostic at best about the broader implications of the nuclear age, from the immediate bomb deaths, to the health effects on workers and their families and neighbors, to the epochal contamination of the land. Visitors are not asked to reckon with that; instead they experience nuclear history as an entertaining excursion, even as nostalgia.

The carefully crafted, intentional preservation—and presentation—is in stark contrast to another iconic site from the nuclear age: Chernobyl.

With a 30-kilometer radius the Chernobyl exclusion zone circles the former Soviet nuclear plant, on the outskirts of the Ukrainian city of Pripyat. The death toll from the reactor meltdown is disputed, but at least 28 people died in the explosion or from radiation poisoning in the immediate aftermath. Many cases of thyroid cancer and birth defects in Ukraine and neighboring Belarus have been attributed to the accident, which remains the worst nuclear disaster in history.

“If you read studies by groups like Greenpeace and other [nongovernmental organizations] interested in the environment, they would give higher numbers. If you read studies by the nuclear power lobby, you get lower numbers,” says David Moon, a historian at the University of York in the United Kingdom who has toured the exclusion zone.

Along with producing fissile material, such as plutonium, nuclear reactors can be used to produce electricity. The heat produced when atoms split can be captured to boil water, producing steam to drive turbines.

Ukrainians have mixed feelings about tourists visiting the area; mostly, they don’t understand why anyone would want to come.

The four Chernobyl reactors were designed to do both: produce plutonium and generate electricity. The reactors used graphite as well as water coolant. But when run at low power, the reactors were unstable, a result of a flawed design that led to the devastating accident. On April 26, 1986, a power surge caused Reactor Four to overheat, producing a steam explosion that blew the top off the reactor and exposed the radioactive core to the open air. A fire raged for 10 days, releasing copious amounts of radioactive particles into the atmosphere.

Sergii Mirnyi arrived five days into the disaster. He was commander of the Chernobyl radiation reconnaissance platoon, which came to survey the damage. Now Mirnyi is a writer in residence at National University Kyiv-Mohyla Academy in Kiev, Ukraine, and an adviser for several Chernobyl survivors’ and tourism groups.

He says the lasting effects are more psychological than physical and trips to Chernobyl enable visitors to understand what happened. Survivors felt isolated by their government and its silence in the immediate aftermath of the accident. By welcoming tourists and visiting the site themselves, survivors can reframe the area’s legacy, turning it into a story of recovery and hope rather than loss, Mirnyi says—just as nature has begun to reclaim the land.

Moon, however, said he experienced a sense of foreboding while walking around the abandoned buildings, but that was mostly because he remembered the accident; he was a graduate student in Leningrad in April 1986 and had to visit Kiev shortly after the meltdown.

“It was a dreadful time. We didn’t know what was going on,” he recalls. Shortwave radio broadcasts from Western media portrayed the disaster as catastrophic, but Soviet authorities did not discuss details, which left people fearful and uncertain.

In the days after the meltdown, crews hastily encased the reactor in a concrete structure called a sarcophagus, designed to limit additional release of radioactive material. In November 2016 workers covered the sarcophagus with a gigantic steel shell measuring approximately 843 feet across, 355 feet high, and 492 feet long, large enough to enclose the Statue of Liberty. The structure is designed to contain the reactor’s radioactivity for 100 years.

Throughout 1986 officials evacuated about 115,000 people from the most heavily contaminated areas, and another 220,000 people were moved later, according to the U.N. Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation. The Soviet government also cut down about a square mile of pine forest that had been contaminated and buried the wood.

But the trees came back. Pripyat is now a 30-year-old forest, with trees overtaking squares, sidewalks, roads, and even the insides of buildings, says Moon. And that forest is flush with animal life. Moose, deer, brown bear, Eurasian lynx, and wolves have overtaken the exclusion zone; with no humans hunting them or ruining their habitat, they have flourished despite high radiation levels. Przewalski’s horses, a rare and endangered subspecies of wild horse, were introduced to the exclusion zone in 1998, and their numbers are increasing, according to biologist James Beasley of the University of Georgia, who studies Chernobyl wildlife.

Left, In the years that followed, some residents—called samosely, or “self-settlers”—returned to their homes. Others never left at all, such as Yelena Muzychenko, who had lived in her small Belarusian village without electricity or running water for 18 years when photographed in 2004. Center, Wildlife, including foxes, wolves, Eurasian lynx, and endangered Przewalski’s horses, have found refuge in the radioactive forests of the exclusion zone. Right, To the bewilderment of many locals Chernobyl’s ruins have also drawn tourists.

“There’s a lot of evidence that a lot of these species are increasing in abundance after humans have abandoned the landscape. It has started to rewild,” Beasley says.

That abundance of flora and fauna belies the truth that Chernobyl is unsafe. The animals are there because the humans are not, according to Beasley; humans have a bigger negative impact than radiation. In as-yet-unpublished work his research team has found that wolves are concentrated near the center of the exclusion zone, in the most highly contaminated area.

“We do know these animals are accumulating very high levels of radiation, but the radiation is not uniform throughout the landscape. With our wolf work we are trying to figure out how variable that is,” he says. “Wolves are heavily hunted outside the zone, so they are concentrating their activities inside the zone—where there is less human influence but more radiation.”

The exclusion zone exudes a postapocalyptic feel, according to visitors. It serves as a Cold War version of Pompeii, a time capsule from another era.

Beasley visits about once a year and drives through forests on the Belarusian border. Lush woods give way to the Pripyat River, which is largely unmanaged by humans; lacking dams, levees, and agricultural canals, the river is free to meander.

“It looks kind of like what a river is supposed to look like before agriculture straightens them out; it’s braided, very winding. It has lots of oxbows coming off it, and in the oxbows you see all kinds of different waterfowl, and birds and eagles flying around,” Beasley says.

Along the roadways, many of which are slow going owing to heaving and potholes, Beasley notices the houses. Much of the exclusion zone beyond Pripyat contains small agricultural towns, which were all abandoned in the days and weeks after the accident.

“Those houses are collapsing around themselves. There are still belongings there. Sometimes there are pictures. You have this really eerie feeling; there is a constant reminder that there were people’s lives that were impacted by this accident,” he says.

Most tourists do not visit these areas, but there are some exceptions. During Moon’s trip the group visited a resident, Ivan Ivanovich, who had worked as a security guard at the power station. He and his wife, who died a few months before the visit, were one of about 100 families who illegally returned to the exclusion zone following the disaster. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Ivanovich was given official permission to stay in his home. He grows fruit and vegetables in his garden, receives a government pension, and buys provisions from a mobile store that occasionally visits. He is accustomed to gawking Western tourists.

“Normally when you have visitors, you would offer them something to eat or drink, but I noticed he did not. He knew we would say, ‘No, thanks very much,’ ” Moon said. “He said his grandchildren never visited because their parents wouldn’t let them come in.”

Most of the tours stay close to Pripyat, where visitors can experience a curated presentation of late Soviet history. Most of the buildings have long since been looted, but on Moon’s tour some rooms in the hospital had been set up to depict a freshly evacuated scene, with equipment set out in an operating theater. Moon’s tour guide wore a radioactivity dosimeter, which would occasionally sound its alarm when the group approached certain areas.

“I thought the idea was to stay away from these hot spots, but our tour guide kept going back to them. He was used to disaster tourism,” Moon recalls.

A couple of private companies offer tours in Chernobyl, bringing visitors who remember the disaster, are studying it, or have only experienced Chernobyl in video games and movies. Dylan Harris, who owns a tour company called Lupine Travel, has taken several hundred clients to Chernobyl since 2008. He visited for the first time in 2006 and founded his company after realizing other people might want to see it, too.

“It is a very moving experience. I’ve now visited numerous times, but I think the one thing that stood out for me on my first visit was the completely unnatural silence in such a huge urban environment,” he says. “Pripyat was a city housing tens of thousands of people, and to see it lying abandoned in decay, it makes it really hit home, the scale of the accident and the effect it had on people’s lives.”

He says Ukrainians have mixed feelings about tourists visiting the area; mostly, they don’t understand why anyone would want to come. The small number of tourism opponents has dwindled, though, since the country’s civil war began in 2014. “I think Chernobyl has been a real boon for tourism in general to Ukraine, and this has become more apparent to people in recent years since the economy is struggling with the ongoing conflict,” Harris says.

Indeed, some Ukrainians are keen to make money on the experience of Chernobyl. I asked Chornobyl Tour, another company that arranges tours of the facilities, about its clients and practices. But the company requested a $60 fee for an interview. I was told this would be discounted by the equivalent of about $20 because I was a journalist, but if Chornobyl Tour’s management didn’t like what I published, I would have to refund the discount. I wondered how the tour operators would want the place portrayed.

An abandoned amusement park (left) and the dilapidated Palace of Culture Energetik (center) in Pripyat, Ukraine, near the site of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Pripyat was home to nearly 50,000 residents before an explosion in April 1986 forced the evacuation of the town and the relocation of all people within a 30-kilometer radius of the plant. Overall, nearly 335,000 were displaced. Right, A tourist visits a deserted building in the Chernobyl exclusion zone, 2011.

According to visitors it would be hard to portray it as anything positive. The buildings in Pripyat are crumbling, and when visitors walk through them, they hear the sound of water dripping everywhere, said Amanda Thomson, a U.K. resident who visited the site in October 2014.

“You avoid puddles and drips through fear that it’s seeped through radioactive structures. The floors are spongy and trees crawl in through decayed window frames,” she wrote in an e-mail. “Its desolation is hard to explain. What radiation can do, and for how long, is staggering.”

Thomson says she is often asked why she wanted to pay Chernobyl a visit, and she has a hard time explaining it to her friends.

“As grim as it sounds, I think I was just attracted to the postapocalyptic visage of the place. A place destroyed by something that everyone tells us should be amazing, because nuclear power is amazing, right?” She says she would recommend the tour to everyone, but she would not go back herself.

“It started as a bit of an adventure through a nuclear wilderness, the only chance I’ll ever get to see a postapocalyptic world, but after the first day of tour I was exhausted,” she recalled. That evening the tour group watched videos and short documentaries about the explosion and the robots tasked with cleanup.

“We saw the remains of parks and playgrounds, churches and schools, apartments literally abandoned. I stood on the bridge where men had watched the ‘lights’ erupt from the reactor with fascination, not knowing they’d be dead in days. It really did change from a ‘cool, not many people do this’ tour to quite a sobering experience that’s genuinely changed my opinion on nuclear energy.”

William Sumner, a nuclear operations officer in the U.S. Army who works on nonproliferation, also called the experience “sobering.” He visited in February 2017.

“Reading about it is one thing, but walking amongst the ruins and trying to comprehend that the people there were getting heavily dosed while watching the event is another. Since absorbing all of the radiation doesn’t come with the associated sights/sounds/smells of other disasters, it would be hard for the residents to understand what was happening to them,” he wrote in an e-mail.

Like Thomson, Sumner said he would recommend the trip to others but for different reasons: he thinks a visit can help people understand what went wrong and how it could have been prevented.

Another former nuclear site, this one back in the United States, offers very different lessons. Colorado’s Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge offers a glimpse of how the nuclear age shaped the American mind-set and is in many ways part of the evolution of the country’s other foundational notions—manifest destiny, the settlement of land, and the use of the earth.

The 5,237-acre refuge, which sits at 6,000 feet in elevation 10 miles from Boulder and 16 miles from Denver, is a windswept prairie full of elk, field mice, mule deer, and coyotes, just as it was for millennia. But from 1952 until 1994 it was a manufacturing, processing, and storage plant for weapons-grade plutonium, with a checkered safety record. After a raid by the EPA and FBI on June 6, 1989, the plant’s operator, Rockwell International, pleaded guilty to 10 criminal violations of the Clean Water Act. The FBI said it had evidence Rockwell dumped toxic waste into drinking water and secretly incinerated radioactive waste, according to coverage of the legal proceedings in the New York Times. Rockwell paid $18.5 million in fines.

During the 1950s and 1960s contaminated runoff flowed through local creeks into Standley Lake, a reservoir supplying drinking water to the metro Denver communities of Westminster, Thornton, and Northglenn. Standley Lake is now protected by a reservoir upstream, but lake sediments still show traces of plutonium and americium. (State health officials say the amounts are so small they pose no public- health risk.)

While the plant was active, occasional mishaps also spewed radioactive particles into the air. A fire in a production building on May 12, 1969, released a “small amount of radioactive plutonium,” according to a report in the Rocky Mountain News.

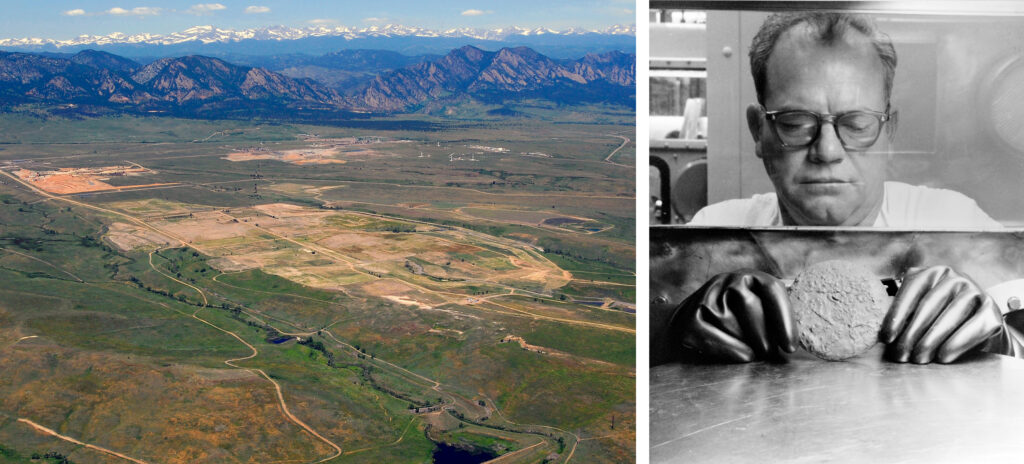

Left, The grasslands of Colorado’s Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge photographed after cleanup, 2007. The refuge is expected to open to the public in 2018, to the excitement of some local residents and the consternation of others. From 1952 to 1994 the parkland was the site of a nuclear-weapons plant, whose waste contaminated surrounding land and communities. Right, A Rocky Flats worker holds a plutonium “button,” the raw material for the nuclear “triggers” made at the plant, 1973.

Cleanup began in 1996 and included the demolition of more than 800 structures, removal of 21 tons of weapons-grade material, and treatment of more than 16 million gallons of water. The site was formally closed in 2006, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service acquired it from the Department of Energy in 2007. The agency is planning to construct a visitor center, parking lots, 20 miles of hiking trails, and interpretive signs; it should open to the public in 2018.

It would be a welcome site. The Denver−Boulder metro area has experienced explosive population growth in the past decade. Visitors to the region’s state and national parks encounter lines of traffic and packed campgrounds and trails. A seemingly pristine, animal-filled prairie just a few miles from town would entice plenty of tourists.

Not everyone is enthusiastic about the park. As in Hanford, people who lived in the communities surrounding Rocky Flats have suffered thyroid cancers and similar illnesses, which they ascribe to the plant’s radioactive materials. Their health has not benefited from years of court dates and drawn-out litigation, says Tiffany Hansen, cofounder of an advocacy group called Rocky Flats Downwinders. She grew up three-and-a-half miles from the site in a development called Quaker Acres and started researching its history when she was diagnosed with benign ovarian tumors in 2015. She believes state and federal officials need more data on health effects of groundwater and atmospheric radiation exposure before opening the reserve to visitors, including children.

“To assume that since the site is no longer active, the site is now a place [where] we can recreate, bring our children, go hiking—I cannot think of anything more disturbing,” Hansen says. “Why is it necessary for us to use these spots to, what, prove a point? Why would we put the public at risk, unless we are trying to say that it’s all good and make it perceived to be safe?”

Turning Rocky Flats into a park may be an attempt to offer a brighter future—albeit one that buries its past. As the land is being restored, on the surface it looks as though humans never did anything at all. Where Hanford’s curated presentation celebrates nuclear technology and Chernobyl’s more anarchic experience acclaims the restorative power of nature in the face of human folly, Rocky Flats may be able to achieve both. Instead of scrubbing the plant’s history from the scrub grass, visitors should experience both aspects at once.

Without a full reckoning of the effects of the atomic age on the land and on people, the whole point of nuclear tourism could be rendered meaningless. Even worse, it squanders its own potentially great power. This obliviousness is especially true for people who came of age after the Cold War petered out, after the Berlin Wall fell, after schoolchildren stopped practicing air raids by hiding under their desks. By 2017 nukes were hip; the atomic age was retro, sepia-toned, and normalized, as Linda Richards says. Snapshots in front of fuel rods and silly selfies at control stations demonstrate that tourists interpret nuclear weapons in ways incomprehensible to the Cold War generation.

But in fall 2017 the world may be on the brink of a nuclear catastrophe, a moment for which the best historical comparison might be the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. North Korea continues to wave its nuclear saber by detonating increasingly powerful subterranean bombs and launching rockets. In the United States, President Donald Trump responds to ballistic missiles with 140-character missives. Millennials and Generation Z may gain an unfortunate appreciation of their elders’ perspective.

In the near future will relics of the nuclear age be vested with new meaning by the tourists who visit them? After all, they are not mere vacation spots but stark messages from the past. Nuclear tourism presents a unique opportunity. People might come to Hanford, Chernobyl, and Rocky Flats for a variety of reasons: to scratch a nostalgic itch, to experience a postapocalyptic vision, or even to reclaim, and acclaim, nature. They may come away with more. In each place history’s presentation has the power to transmute our own experience.