Rudolph Pariser’s extraordinary life story reads like a time line of 20th-century world history. He was born in Harbin, China, to a Russian mother and German father, and later moved to Japan and then the United States in pursuit of an education uninterrupted by the pains of war. This pursuit proved surprisingly difficult, but his unique experience and knowledge of several languages helped him along the way. His journey contributed to his becoming a brilliant physical chemist and, through his codiscovery of a method for computing molecular orbits, a vanguard in the emerging field of quantum chemistry.

Pariser’s father, Ludwig Jacob Pariser, fought in the German army and became a prisoner of war during World War I. After eluding his Russian captors near the Siberian-Chinese border, Ludwig made his way to Harbin, where many refugees of the Russian Revolution also found safe harbor. He found work there as a tutor for the children of a Jewish merchant family and soon met and married Lia Rubinstein, who had fled Estonia (a Russian province until 1918) after her family’s leather factory was destroyed during the revolution. Life in multicultural Harbin exposed the young Pariser to many languages, and he became multilingual at an early age.

In 1936, on the eve of World War II, Pariser began attending classes at an American missionary school near Beijing. One semester into his studies, however, the invading Japanese army leveled the school. Fearing more Japanese attacks on China, Pariser’s parents sent their son away to an American school in Tokyo. While there, he developed a close friendship with his American physical education teacher, Jim Rasbury. One day Rasbury inexplicably vanished, and it wasn’t until years later that Pariser learned that his father had also known Rasbury and that Rasbury was an American spy. When his cover was blown, Rasbury abruptly fled Japan and sought refuge in China, where Ludwig and Lia Pariser helped hide him.

By the summer of 1941 tensions ran high for students at the school in Japan, and Pariser’s parents decided Rudy should go to the United States for his university training. He and his mother left from Yokohama for California aboard a Japanese ship, making what turned out to be the last commercial voyage from Japan to the United States until after the war. His mother planned to return to China after getting Rudy settled in San Francisco, but when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, she was prohibited from traveling back to China for the duration of the war. Pariser and his mother were stuck in America, and their German passports caused them to be classified as enemy aliens, making them subject to curfews and restrictions on their daily activities.

Looking for a way to support himself and his mother, Pariser went to the FBI field offices in San Francisco to apply for a job as a Russian translator. When he got there, he found that the office was headed by Jim Rasbury. Undoubtedly grateful to the entire Pariser family, Rasbury used his government connections to secure well-paying jobs and special identification cards for the Parisers, effectively lifting the restrictions placed on them as enemy aliens.

On Rasbury’s recommendation Pariser began working nights for the war effort in the local shipyards and attending the University of California, Berkeley, during the day, where he studied chemistry under some of the brightest minds of the decade. Among his mentors were Joel Hildebrand, William Giauque, Melvin Calvin, Glenn Seaborg, and Frank Oppenheimer, who substituted for his brother, J. Robert Oppenheimer, while he was away directing the Manhattan Project.

After graduating in 1944, Pariser worked briefly for Kaiser Permanente, but it did not “feel right” to be safely at home with a good job while others were risking their lives in the war. So he soon left to enlist in the U.S. Army. Although the army trained him to use his language skills for the impending invasion and occupation of Germany, Pariser ended up with the signal corps in Joplin, Missouri, where his language talents remained unused for the rest of the war.

When the war ended, his father joined the family in the United States while Pariser took advantage of the GI Bill and a fellowship from the Office of Naval Research to pursue a doctorate at the University of Minnesota. In a move that would help launch his career as a world-renowned chemist, he studied and worked alongside numerous prominent chemists, including William Lipscomb, Frank MacDougall, and perhaps most significantly, his future collaborator, Robert Parr.

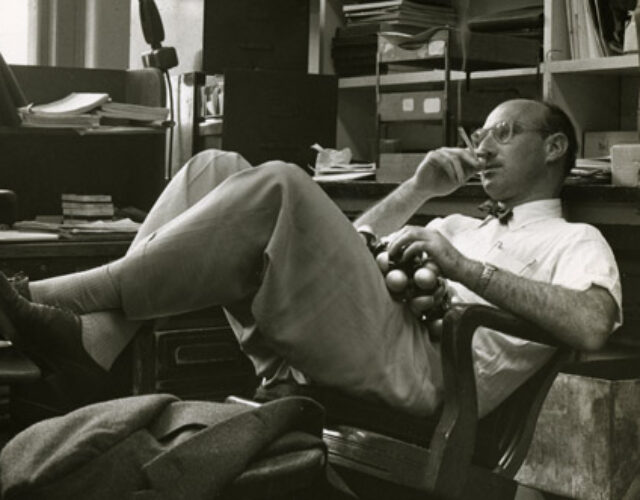

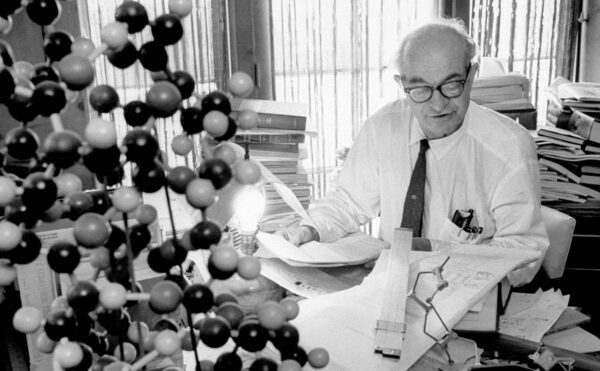

In 1950, after completing his graduate work, Pariser joined DuPont’s Jackson Laboratory in New Jersey, where he studied properties of organic dyes being developed for the company’s new synthetic fabrics. This work led him to consult with his old friend Parr (now on the faculty at the Carnegie Institute of Chemistry) to develop a method of approximating molecular orbitals, now known as the Pariser-Parr-Pople method.

Pariser went on to many other successes, staying at DuPont for nearly 40 years and solidifying his position as a leader in quantum science. Stories of his fascinating and influential career abound, but the lesser-known history of his young life provides a glimpse of the early influences on his career and relates a vital narrative of adversity and human accomplishment.