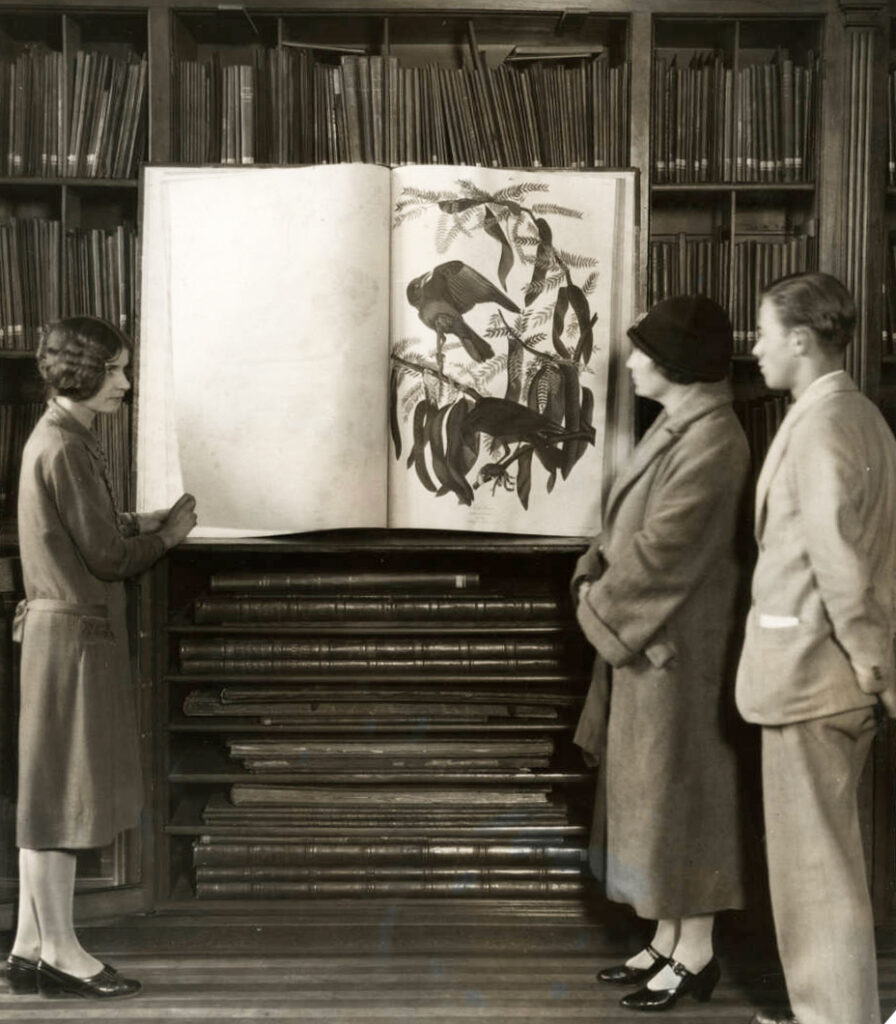

Disaster struck after just 10 pages. The year was 1826, and John James Audubon was not yet the ornithological legend he would become. To the contrary, he was a no-name naturalist stuck in a foreign land, trying to hustle out a book—The Birds of America—to make his name. And 10 pages in, the whole project seemed likely to fall apart.

The issue was the book’s engravings. Audubon painted lush, dynamic watercolors of birds, and an engraver was required to transfer the images onto metal plates for printing, along with colorists to add hues to each page. The Brits working on the book were top-notch, and the first set of plates went smoothly. But then the engraver wrote Audubon with terrible news: he was quitting.

Officially, he did so because his colorists had gone on strike. But Matthew Halley, an ornithologist and historian at the Delaware Museum of Nature and Science, also suspects the engraver saw a way out. Given its sheer size—Audubon planned 435 pages, each one stretching more than three feet tall and two feet wide—The Birds of America would be stunningly expensive, $1,000 a copy (more than $30,000 today). Audubon was financing the book through subscriptions, and they were lagging badly. The strike might have been a convenient excuse to abandon a sinking ship.

Audubon now faced a crisis. He had gambled his future coming to Britain and needed a ploy to win subscribers—fast. He decided to make a few more engravings to woo potential patrons, and they needed to be as enticing as possible. To salvage his career, he turned to a creature unlike anything Britain’s ornithologists, or anyone else, had ever seen.

Two years earlier, in the spring of 1824, Audubon had tucked his portfolio of watercolors under his arm and traveled from Kentucky to Philadelphia, the epicenter of American science. He was hoping the prestigious Academy of Natural Sciences there would publish his book.

The academy turned him down flat. Historians have debated the reason for this embarrassing rejection for nearly two centuries, but the leading theory holds that the academy’s vice president, George Ord, had it out for Audubon. Ord—described by Richard Rhodes as a “long-faced, quarrelsome, wealthy English dilettante”—had recently completed a multivolume book on North American birds. Rhodes and other historians argue that Ord saw Audubon’s book as competition and purposely scuppered it.

Audubon returned home crushed. But, unwilling to abandon the project, two years later he reluctantly sailed abroad to seek publication. “America being my country,” he later wrote, “and the principal pleasures of my life having been obtained there, I prepared to leave it with deep sorrow.”

Audubon arrived in England in July 1826. Initially, things went well. He arranged for exhibitions of his paintings in Liverpool and Edinburgh and drew good crowds for each. People marveled at how animated and realistic the birds looked in his work.

Riding this wave of acclaim, Audubon quickly secured a publisher. But then the engraver dropped out, plunging the book back into doubt. The project seemed cursed.

A friend hastily arranged for a showing of his paintings in London at the Royal Society, and the esteemed naturalists there were every bit as wowed as the gallery-goers in Liverpool and Edinburgh. “My portfolios were opened before this set of learned men,” Audubon recalled, “and they saw many birds they had not dreamed of.” With their endorsement in hand, Audubon secured a new engraver.

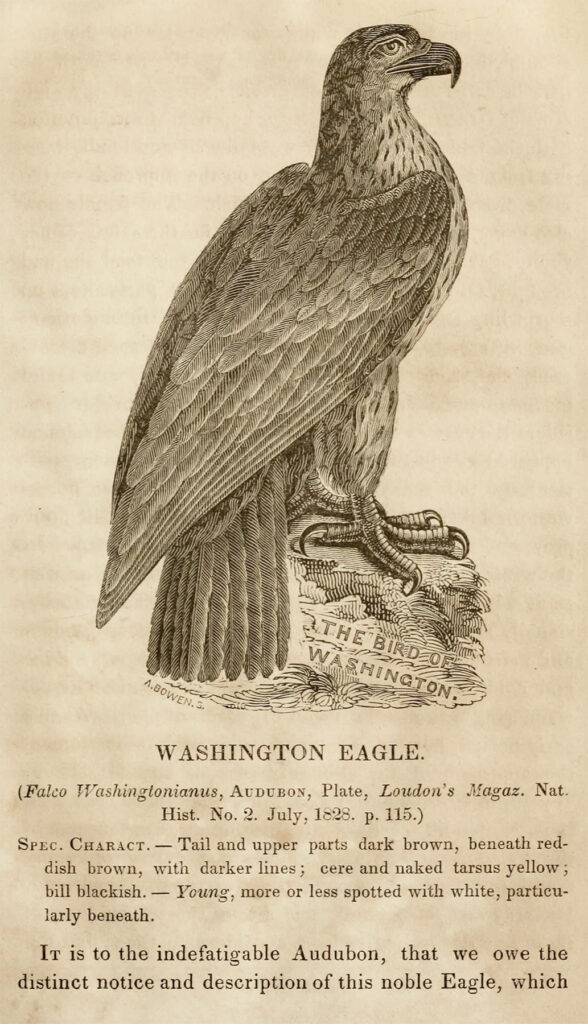

But the society’s backing alone did not ensure that the subscribers needed to keep the project afloat would materialize. Audubon needed a magnificent new print to entice potential patrons. Only one work would do—his painting of the Bird of Washington, North America’s largest eagle and a previously undescribed species.

The painting showed the bird perched atop a crag, its dark brown wings crossed behind its back. It resembled a bald eagle, minus the white feathers on the head or tail. Its lower bill was also longer, and the skull flatter. Most significantly, the Bird of Washington was roughly 25% larger than the bald eagle, with a 10-foot wingspan.

Audubon’s gamble with the print paid off. A few crucial patrons stepped forward, including King George. It’s not clear why the eagle appealed to them, but Halley suggests the bird’s name—which Audubon selected after arriving in England—was crucial.

The United States had recently fought two wars with Great Britain—and somehow, the young republic had gone blow for blow with the greatest military power in the world. Britain might have whipped Napoleon, but not George Washington—a name that demanded respect, especially among the many upper-class Englishmen sympathetic to American ideals of democracy and religious tolerance.

Indeed, Audubon even posed the bird like a military general—gazing into the distance, its chest thrust out. As English ornithologist William Swainson remarked in a review, “we can discern . . . much of the mild dignity of the great American patriot, in this his emblem, as can well be expressed in the head of a bird.” Swainson called Audubon’s book “perfection” and begged others to subscribe.

In truth, this review wasn’t quite on the up and up. In exchange for writing it, Audubon had promised Swainson a copy of the completed work at a steep discount. Regardless, the ploy worked: subscriptions poured in. The Birds of America took flight in England, propelled on the wings of the Bird of Washington.

But it turns out Audubon’s scheming reached well beyond a mild bribe. “Of all the large, charismatic bird species that Audubon could have chosen at this critical juncture,” Halley notes, Audubon chose a “painting of a ‘new’ species of which . . . he had no physical evidence.”

In short, no one knew whether the Bird of Washington was real.

To those paying attention, certain clues called the bird’s existence into question. A note inked onto Audubon’s painting described the bird as male. But when Audubon exhibited the painting in a gallery, an accompanying catalog said the bird was female. Was this a simple mistake? Or could he not keep his story straight?

Furthermore, was it really possible that every other ornithologist in the United States had missed such a large, majestic bird? Uneasily, Swainson and a few colleagues realized that the only “proof” they had seen of the bird’s existence was in a painting. Had Audubon made a mistake—or even misled them?

The only way to settle the matter would be to examine a specimen. In fact, according to the scientific standards of the time, naturalists could not officially define a new species without a specimen. Audubon knew this, and after his triumph at the Royal Society, he wrote an essay for its zoological journal recounting how he had seen a Bird of Washington on three occasions back home and shot one the final time. This “fresh-killed specimen,” he said, served as the model for his painting.

That was reassuring. But scientific standards also required naturalists to deposit their specimens in a museum or otherwise make them available for their peers to examine. In the flush of excitement over Audubon’s painting, Swainson and others had let that requirement slide. But as they sobered up, they began to wonder: did Audubon really have a specimen?

No, he didn’t. The essay that chronicles the shooting is vague on dates, but Audubon claimed to have seen one in roughly 1814 and 1817, then shot one around 1819. He also states that he had not seen one since that last encounter. However, in a diary entry from 1820 that Halley unearthed, Audubon admits that he had no specimen in his possession—and, worse, that he still had no idea whether the raptors he had seen were a separate species or simply immature bald eagles. (Bald eagles acquire their distinctive white plumage as they mature.)

Swainson had no way of knowing this confession. Instead, a rumor reached him in 1830: a stuffed Bird of Washington had turned up near Philadelphia. He breathed a sigh of relief. He hadn’t been rooked after all.

In truth, Audubon had passed through Philadelphia in March 1830 and had sowed the rumor himself.

That spring, Audubon met a naturalist friend, Richard Harlan, and they visited a zoo that supposedly had captured a Bird of Washington. Harlan took one look and was convinced. Audubon proved more discriminating. He declared it an immature bald eagle, which would soon molt and change color. And so it was. The zoo’s bird matured and took on the familiar plumage.

But that wasn’t the only alleged Bird of Washington around. A taxidermy shop near Philadelphia had another on display, so Harlan and Audubon dropped by. The sight left Harlan glum: it looked just like the bird at the zoo, another immature bald eagle. To his surprise, though, Audubon contradicted him. This, Audubon declared, was an exemplary specimen of the bird. Harlan soon came around to his point of view.

This was likely a clever gambit on Audubon’s part. Being dead, the bird would never molt and prove him wrong. He also probably suspected that Harlan would spread word about the discovery. Indeed, Harlan did such a good job of gabbing that even Swainson in England heard the rumor.

Unfortunately for Audubon, an excited Harlan did more than gab. Without Audubon knowing it, Harlan went back, bought the bird, and deposited it with the Academy of Natural Sciences. This was good, standard science—and a serious threat to Audubon. Any curious ornithologist could now unravel the rumor. And one soon did—his old enemy, George Ord, the very man who had torpedoed his book’s publication six years earlier.

In describing Ord as a quarrelsome dilettante, Rhodes was only half correct. He certainly had a cranky side, but he was no bungler. Historically, most of what made him a villain is his clashes with Audubon, who enjoyed a pristine reputation for nearly two centuries. Historians have long revered Audubon’s frontier machismo, his vivid writing, and the brilliant way he fused science with art. The fact that a granddaughter burned most of his diaries after his death has hindered efforts to fact-check Audubon and render his life more accurately.

But with the Bird of Washington, the grouchy Ord saw through his rival’s charisma and growing status. Ord examined the stuffed one in Philadelphia alongside two bald eagle specimens and found zero difference between them. He also compared this supposedly authentic specimen with Audubon’s painting and found conspicuous discrepancies. As Ord documented, the skull in the painting was too flat, and Audubon had distorted the shape of the bill, stretching the lower part too far and adding a “tooth-like process” to the upper part. For an artist of Audubon’s caliber, Ord concluded that these could not be simple mistakes. Instead, the painting was “calculated to mislead.”

Alas, Ord did nothing with these findings. Audubon was simply too famous by that point, and he feared abuse from Audubon’s legions of admirers. As he grumbled privately in a letter, “I should have a swarm of hornets about my ears were I to proclaim to the world all that I know of this impudent pretender and his stupid book.”

As a result, the Bird of Washington appeared in ornithology texts around the world, on the strength of Audubon’s reputation alone. It proved popular among the American public as well and became a beloved symbol of the young United States. People even penned songs and odes to it. (“I laugh as the legions of tyranny flee,” one read, “And they call me the bird of the free.”)

Still, by the late 1800s, naturalists couldn’t help but notice that no one had ever found another Bird of Washington in the wild. But given Audubon’s heroic status, historians and biographers dutifully played this down—claiming that he had made an innocent mistake or suggesting that the species had gone extinct. They were unwilling to entertain the idea that the Bird of Washington was simply, in Halley’s words, “the cornerstone of a highly successful . . . marketing strategy and a lie that Audubon took to the grave.”

The publication history of The Birds of America looks quite different in light of Audubon’s deceptions. The art was certainly gorgeous, but naming a new species in a commercial publication essentially circumvented peer review. In addition, Halley found evidence that flips the narrative on Audubon’s initial, seemingly unfair rejection at the hands of the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Though historians long assumed Ord had torpedoed Audubon’s book out of jealousy and fear, in truth Audubon dug his own grave. Upon arriving with his portfolio in Philadelphia in 1824, Audubon began spreading rumors that the ornithologist Alexander Wilson—Ord’s late mentor and a beloved figure in Philadelphia science—had been stealing Audubon’s work. Specifically, Audubon swore that Wilson had stayed with him two weeks in Louisville in 1810, during which time he examined Audubon’s specimens, including several new to science. Wilson then allegedly published descriptions of them without Audubon’s consent or attribution. According to Audubon, Wilson was a thief and a liar. Moreover, given that Ord had shepherded Wilson’s book to completion after the latter’s death, Audubon was implicitly accusing Ord of playing a part in this conspiracy.

In reality, Wilson had spent just five days in Louisville and stayed at a hotel. He did look over Audubon’s drawings one morning, then went hunting with him two days later. But Wilson encountered no new species, either in Audubon’s collection or anywhere else during his journey. We know this because Ord had Wilson’s diaries in his possession and twice produced them in public so people could read Wilson’s own account. The whole incident made Audubon look reprehensible, Halley notes, and almost certainly led to the rejection of his book.

It’s not clear why Audubon lied like this. Perhaps he was just trying to puff himself up. Or, as Halley speculates, perhaps Audubon was trying to ingratiate himself with someone whom he assumed (incorrectly) despised Wilson, and the man turned around and exposed Audubon. Regardless of his motivation, the rumor bent back and bit Audubon instead.

Nevertheless, by the time Audubon died in 1851—65 years old, bereft of molars, beset with dementia—his legacy as a pioneering artist, scientist, and all-around great American seemed secure. His legend only grew in the century and a half after his death. Charles Darwin himself cited Audubon three times in On the Origin of Species, and to this day, he has multiple species of birds named after him, as well as the Audubon Society, one of the best-known conservation organizations in the world.

But Audubon’s legacy now seems in serious danger. In addition to the exposure of his fraud, historians have unearthed evidence that Audubon owned slaves and ravaged the graves of Native Americans to harvest their skulls for an anthropologist in Philadelphia. In response to such revelations, dozens of local chapters of the Audubon Society—including New York, Philadelphia, Tucson, and Chicago—have dropped Audubon’s name in favor of “Bird Alliance.” The naturalist still has his defenders—people enthralled with his art and life, who excuse his lies as “tall tales” and his atrocities as products of his time. But others see a just comeuppance—part of an exposure that’s long overdue.