One day in the early 1920s, a doctor in Austin, Texas, castrated three men at an insane asylum. These were especially dark days for psychiatry, when doctors resorted to extreme measures in trying to cure people. Castrations were sadly common.

But what happened next was less common. The doctor diced up the amputated testes with a razor, quickly dunked them in preservative fluid, then rushed them over to the University of Texas, to a biology lab run by his former professor, Theophilus Painter.

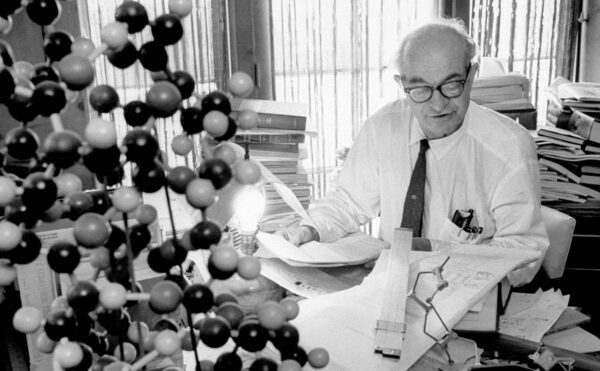

At the lab bench, Painter was known as a tinkerer. He once said you couldn’t be a good cell biologist unless you could repair a Model T with nothing but wire and some pliers. His primary research involved chromosomes—long bundles of DNA in the nuclei of cells. In 1923 he determined that the X and Y chromosomes determine sex in mammals, and in parallel with that work, Painter tried to determine how many chromosomes humans have overall.

It was a deceptively simple question.

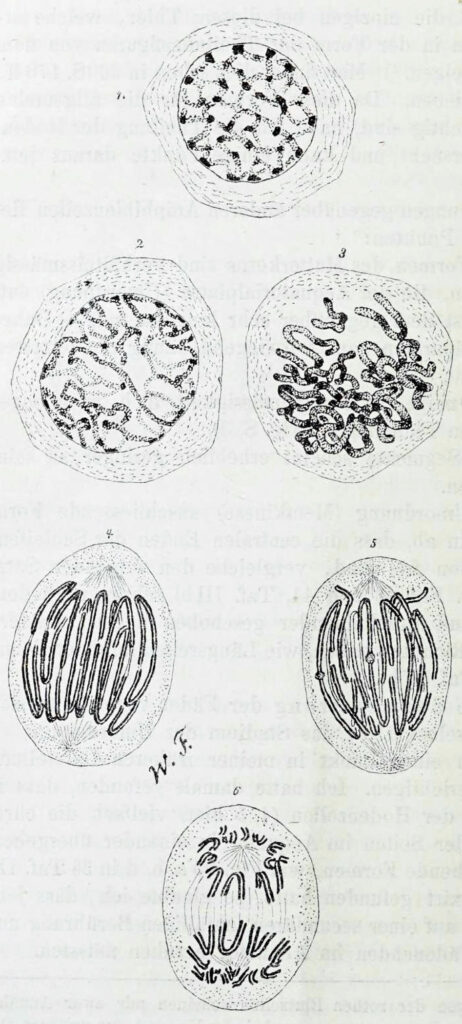

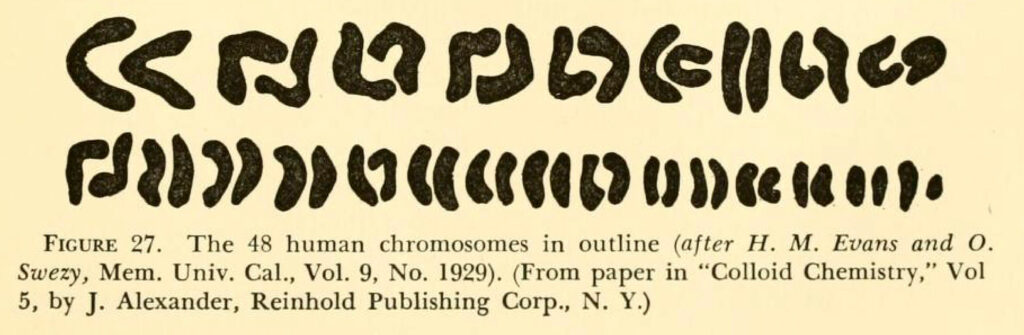

Chromosomes are devilishly hard to count. They’re microscopically tiny, and they’re the same color as the rest of the cell, invisible to the eye without the use of special dyes. Worst of all, chromosomes are not the compact X shapes you might remember from high school biology, at least not normally. In their usual state, chromosomes unspool into long, extended strands, strands that wrap around each other and get tangled up with other chromosomes, like a pile of overlong spaghetti noodles. Looking at them, it’s hard to know where one stops and another starts. Counting them in that state is impossible. Before 1923, guesses for the number of human chromosomes ranged from 8 to 64.

But Painter had figured out a better counting method. When cells divide, they divvy up their chromosomes; during the process, they cinch the tangled chromosomal loops together to make them easier to separate. This also makes them easier to count—although, not that easy; they still overlap each other. Painter planned to find cells in the middle of dividing, inject wax to halt the process, then count as best he could.

The flaw with Painter’s plan was that adult cells don’t divide very often. In fact, the only adult cells that do divide regularly are the cells in testicles that produce sperm, which divide millions of times per week. If Painter wanted to catch cells in the act of dividing, sperm precursor cells were his best shot.

Unfortunately, those cells have to be fresh. After death, chromosomes start to clump together, which makes counting even more of a headache. To compound this problem, people in the early 1900s rarely donated their bodies to science, making it hard to procure human tissue. Which is why Painter called on his former student in the asylum. He simply couldn’t get fresh testicles another way.

Painter wasn’t alone in resorting to such dubious methods. Other biologists were known to lurk near gallows to harvest hanged criminals’ testicles. Biologists reasoned that if castrations and hangings were going to happen anyway, they might as well not let research opportunities go to waste.

Painter’s specimens came from two Black men and one white one. After injecting the cells with paraffin, he prepared microscope slides using the standard procedure of the day, which involved slicing the cells incredibly thin, thin enough to allow light through.

Unfortunately, if you’re trying to count chromosomes, chopping them into pieces makes the task even harder. And in comparing multiple slides, sometimes he counted 46 chromosomes, sometimes 48. And no matter how many times he recounted, he simply couldn’t decide.

He finally took a deep breath and made an educated guess. He published a paper declaring humans have 48 chromosomes.

Biologists were happy to have the number resolved, even on a scientific coin-flip. And the paper did have a positive effect, establishing that Black people and white people have the same number of chromosomes. That refuted a nasty theory, partly rooted in the eugenics movement of the era, that Black people had fewer chromosomes and might therefore be a different species. Painter argued otherwise, that we all have the same number.

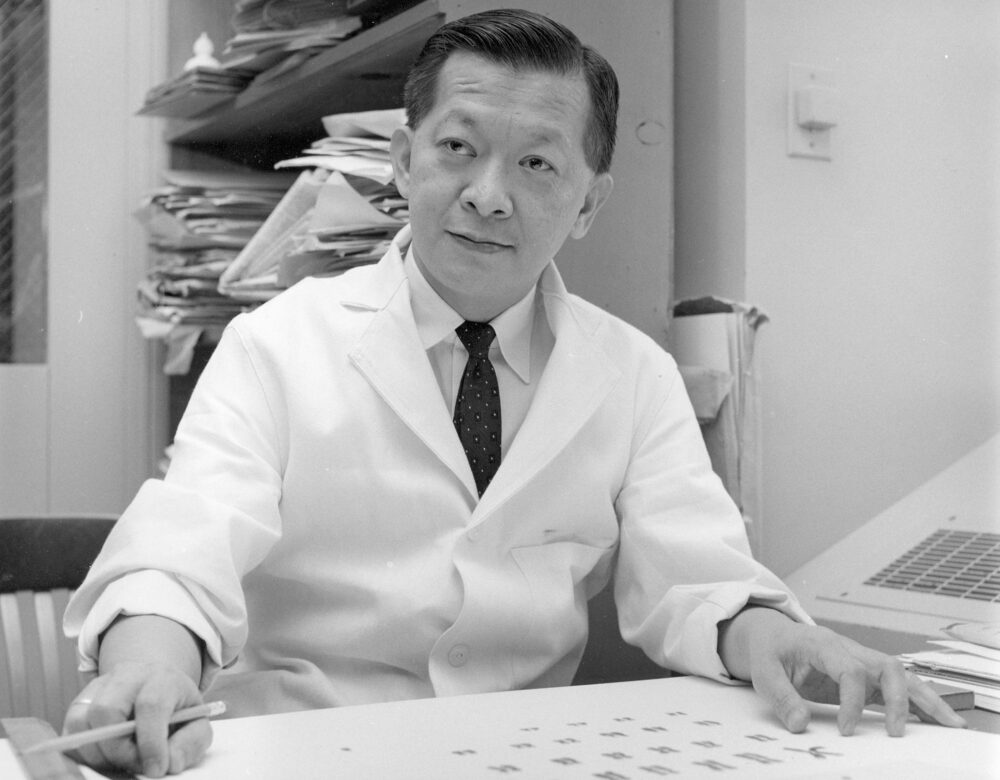

After that, 48 became enshrined as the standard number for humans, and Painter’s work began appearing in textbooks across the world. It would continue to appear year after year, decade after decade—until biologist Joe Hin Tjio got involved.

Tjio was born on the island of Java in 1919. His father worked as a photographer, and Tjio grew up helping out in the darkroom. But he gravitated more toward science, and by the 1940s was working as a research biologist to breed disease-resistant potatoes.

That research was interrupted in 1942, when Japan invaded Java during World War II. For reasons that aren’t clear, Tjio was thrown into a concentration camp and tortured. Despite this brutalization, he spent his time there comforting fellow inmates, even knitting underwear and sweaters for them to replace their ragged clothes—a gesture of real decency in an otherwise ghastly place.

After Java’s liberation in 1945, Tjio took a Red Cross relief ship to Holland and resumed research, bouncing around to labs in Copenhagen, Spain, and Sweden. In Sweden he also met biologist Albert Levan, and the two became friends and research partners, with Levan acting as senior scientist.

Levan had started his career working on plants, breeding sugar beets and clover. By 1955 he was studying the roots of plants that had been exposed to toxins. Under the microscope, he noticed the plants’ chromosomes looked damaged. This intrigued him, because it looked similar to damage he had seen in the chromosomes of cancer cells. Levan decided to pursue this potential connection between damaged chromosomes and cancer and asked Tjio to join his project.

By that point biologists had far better methods for studying chromosomes than Painter had. They had developed better dyes, making chromosomes stand out more in cells. They had also developed a superior preparation technique, called “the squash.” Instead of infusing cells with wax and slicing them, they simply smooshed them under a slide, which kept chromosomes whole and intact.

Levan then incorporated a neat trick he had learned from his research on plants. Crocuses produce a chemical called colchicine, which happens to arrest cells when they’re dividing—freezing them at the very moment when chromosomes are most compact. As a final advantage, Tjio and Levan didn’t need to lurk near the gallows for human tissue. Sweden had legalized abortion in 1938, so Levan had access to fetal cells, which divide far more often than adult cells.

Tjio was a night owl, often working straight from sunset until dawn. He also tended to work through holidays. So in late December 1955 (or perhaps early January), while Levan was away on Christmas vacation, Tjio fired up his microscope one night around 2 a.m. and began examining slides of fetal lung cells. Drawing on his experience in his father’s darkroom, he rigged up a special camera to take pictures of what he saw through the objective lens, then blew up the photographs to examine them.

In doing so he found something odd—he counted just 46 chromosomes. Confused, he grabbed a different slide and began totting up chromosomes on that one. Once again, he got 46.

Tjio eventually counted chromosomes in more than 250 cells; by the end, he was certain Theophilus Painter and all the textbooks were wrong. Humans don’t have 48 chromosomes. They have 46.

Tjio had had a solid but not spectacular career before this, mostly working under Levan’s shadow. Now, at age 36, he had discovered something colossal—a defining feature of human biology. Indeed, given that chimps, orangutans, and gorillas all have 48 chromosomes, it’s one of the major things that separate us from our closest primate relatives.

Tjio waited impatiently for Christmas vacation to end, then broke the news to Levan. Levan was equally wowed, and they agreed to rush a paper into print. For unknown reasons, Levan took the lead writing it. And when he showed a draft to Tjio, Tjio was stunned: Levan had listed himself as the primary author.

To be sure, this had happened before. Tjio and Levan had published five papers together over the previous decade, and Levan had always listed himself first. But in those cases, Levan had participated in the lab work. And none of those other projects amounted to such a fundamental discovery.

When Tjio protested the order of the names, Levan reminded him that senior scientists always got top billing. That’s the way things were done. Tjio pressed the matter, and tensions escalated between the men—to point where Tjio threatened to destroy the slides and photos if his name wasn’t listed first.

An indignant Levan finally agreed. The incident ruptured the two men’s friendship, but when the paper appeared in January, Tjio got the recognition he deserved.

The paper startled biologists, who wondered how they could have missed such a fundamental fact. Tjio’s discovery also opened up new avenues of research into cancer and human evolution. Equally important, the technique Tjio used to accurately count chromosomes also allowed doctors to pinpoint the cause of several medical disorders, including Down syndrome (the result of an extra copy of chromosome 21) and conditions that arise from a variable number of sex chromosomes (XXY, XYY, X0, and so forth).

Such revelations made Tjio a scientific star, and job offers poured in from several places, including the United States. Although tempted to move—the United States had far less hierarchical labs than Europe—Tjio had read all about Joseph McCarthy’s Communist hunts and feared living there. But Indiana University geneticist Hermann Muller, a Nobel laureate, steadily wooed Tijo, in part by sending him clips from the New York Times that criticized McCarthy. This impressed Tjio enough to give the United States a chance. He ended up thriving, working 37 fruitful years at the National Institutes of Health in Maryland, mostly on cancer and the genetic basis of mental disorders.

Tjio never learned to drive and lived on NIH’s campus in an apartment. In interviews toward the end of his life, he still grumbled about Levan trying to pull one over on him. He also continued taking photographs. He died in November 2001 at age 82.

For his part, Theophilus Painter was deeply embarrassed by the revelation that he had overcounted the number of human chromosomes. That work was supposed to be the culmination of his career, and it was dead wrong.

To be fair, new lab techniques had given Tjio a significant advantage over Painter. But those techniques can’t explain why other scientists didn’t notice the mistake in subsequent decades. In fact, after his 1956 paper, Tjio went back and studied pictures of human cells in old textbooks. And with his eyes opened, he could clearly count just 46 chromosomes in some of them; other scientists could have done the same. But the authority of Painter’s supposedly definitive study had blinded them. This decades-long collective error about the human chromosome number was a classic example of Einstein’s dictum that “it is theory that decides what we can observe”—even with something as deceptively simple as counting.