An estimated 30,000 people gathered outside Stafford Prison on 14 June 1856 to witness the hanging of William Palmer, also known as Palmer the Poisoner. His had been the trial of the century, gripping the public imagination in Victorian Britain. The case was so notorious that, to avoid a prejudiced jury, the trial was moved by a special act of Parliament from its local jurisdiction to the Old Bailey in London (which served only to heighten interest in the case).

After training in medicine, Palmer returned to his native Rugeley in Staffordshire, married a local woman, and seemed destined for the quiet life of an English country doctor. But one element of country life proved to be his undoing—horses. Within a few years his obsession with horseracing and betting led him to essentially abandon his practice. He fell deeply into debt and—inexplicably—his closest relatives started dying.

Alfred Swaine Taylor, author of A Treatise on Poisons in Relation to Medical Jurisprudence, Physiology, and the Practice of Physic, was often called as an expert witness at trials, including that of William Palmer.

First to die was his mother-in-law, in Palmer’s home in 1849. Palmer’s wife inherited a trust that upon her death would revert to the mother-in-law’s family. Palmer then took out three life insurance policies on his wife totaling £13,000. Mrs. Palmer died in September 1854. In January of the following year, Palmer insured his brother Walter, again for £13,000. Walter died that August. The insurance companies, now suspicious, refused to pay and assigned a private detective to the case. Palmer’s now desperate financial state led to another alleged murder. In November his associate and betting partner John Parsons Cook won a handsome sum, then grew strangely ill. Palmer collected the winnings, and after several days of his ministrations, Cook too died.

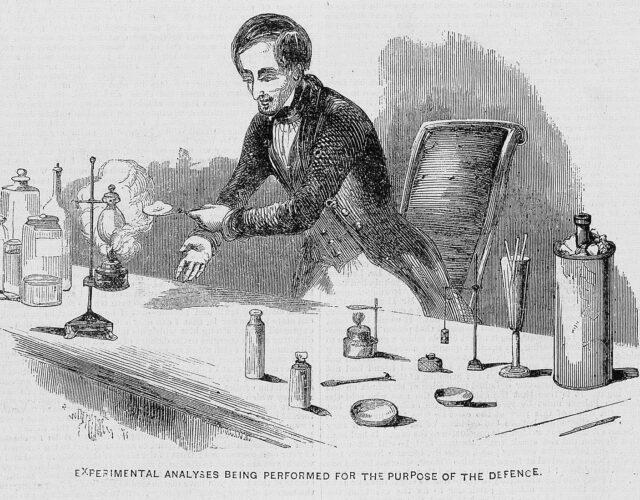

At this point the father of English toxicology, Alfred Swaine Taylor (1806–1880), became involved. Taylor had written the book on poisons, A Treatise on Poisons in Relation to Medical Jurisprudence, Physiology, and the Practice of Physic (London, 1844). When an inquest was called into Cook’s suspicious death, the stomach contents and viscera were sent to Taylor at Guy’s Hospital in London for chemical analysis.

Taylor was at the height of his career. The pioneering toxicologist had been Lecturer in Medical Jurisprudence at Guy’s for 25 years, his Manual of Medical Jurisprudence was in its fifth edition, and he was a seasoned and effective witness for the prosecution. He became the star witness in the case, ensuring Palmer’s conviction.

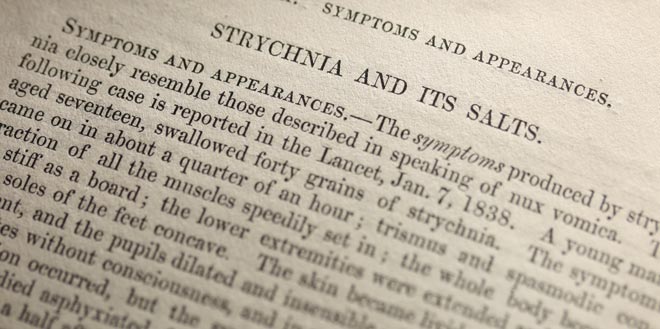

Ironically, it was not chemical analysis that sealed Palmer’s fate. Taylor testified that strychnine—which Palmer had purchased in the days before the murder but could not account for—was difficult to test for even in controlled laboratory conditions. Instead Taylor told the court that the spasms Cook displayed in his paroxysms of death could occur only in cases of tetanus and strychnine poisoning. With tetanus ruled out, Taylor deduced poison.

Even after his conviction Palmer never confessed to the crime. He went to the gallows saying, “I am innocent of poisoning Cook by strychnine,” an enigmatic denial that, paired with ambiguous forensic evidence, has created an enduring mystery.