All she wanted was to look normal. As a young girl in Canada, a car accident had crushed her nose, and the resulting dents and scars left her horribly self-conscious. She felt she never fit in with her peers.

After a wayward youth marked by drug use, she turned to theft to support her addiction, and in the late 1950s, at 28, she was incarcerated at Oakalla Prison near Vancouver. She made the most of her time there, taking classes on typing and English grammar and entering drug counseling. But however gratifying, these services couldn’t fix her main source of distress—her ugly, battered nose.

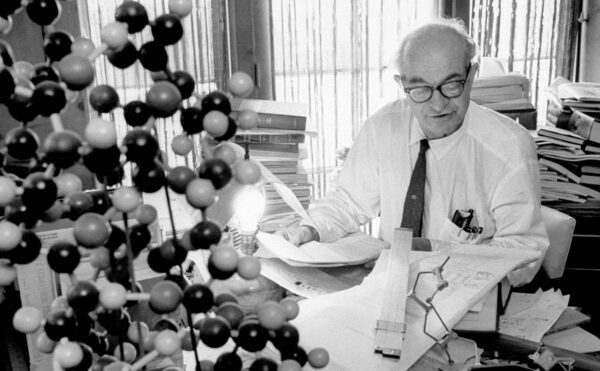

One day, however, the woman learned that a plastic surgeon who volunteered at Oakalla was offering to fix prisoners’ faces for free. His name was Edward Lewison, and he had some unorthodox ideas. Namely, that scars and facial deformities marked people as social outcasts and drove them into crime.

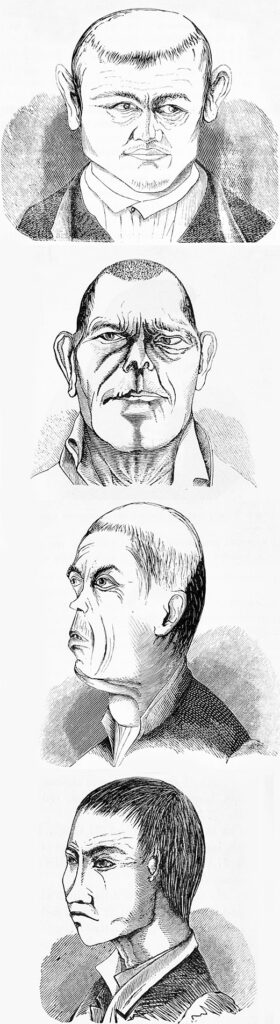

Theories linking looks and criminal behavior were nothing new. A century before, an Italian doctor and eugenicist named Cesare Lombroso promoted the idea that certain facial features—jutting jaws, sloping foreheads, big ears—indelibly marked some people as criminals, partly because those features revealed a reversion to a savage, ape-like ancestor with no impulse control. Lombroso even boasted that he could pick out criminals from photographs alone.

Lombroso’s theories had been debunked by the 1950s, but their influence lingered in Lewison’s notion that facial defects pushed people into crime—especially defects in children. “These children, when they grow up, become weaklings in character and are unable to earn an honest living,” he wrote. Being “barred from the normal community of man,” they use crime “as their way of getting even with nature and society.” If that was true, Lewison reasoned that plastic surgery could fix the problem. By giving people a new face, he could give them a new life.

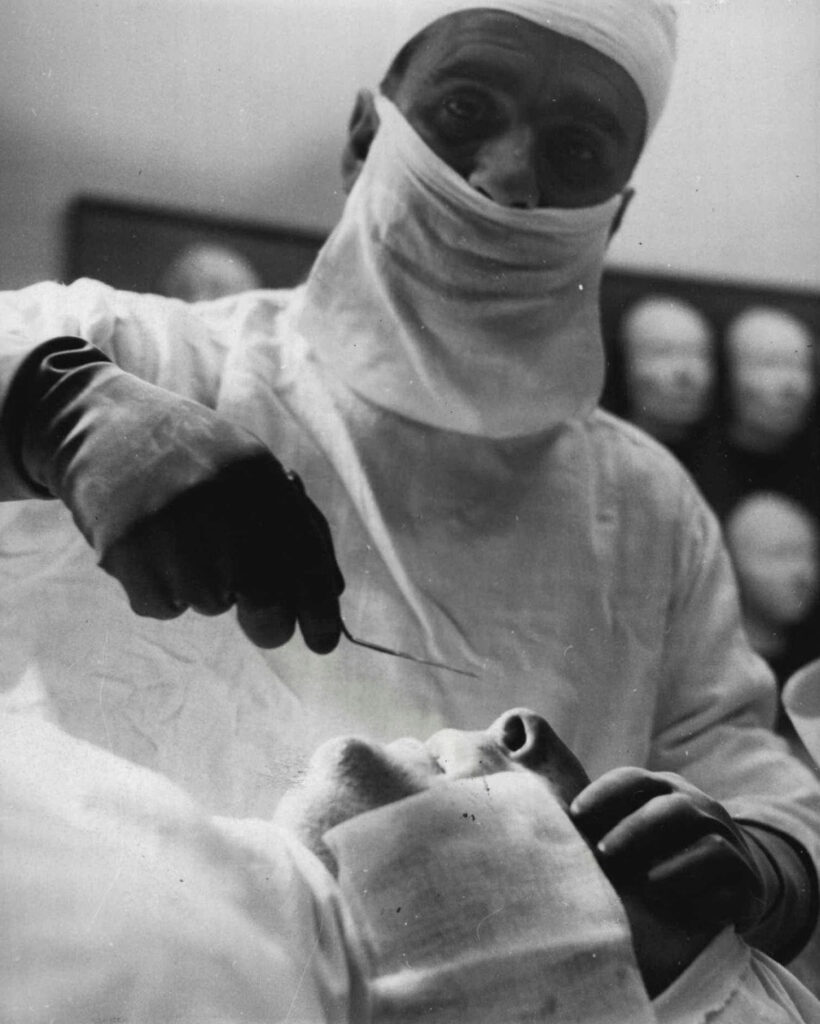

Lewison saw plenty of opportunities to test his theory at Oakalla—the prison population, he said, was rife with broken noses, scars, gnarled teeth, and bulging ears. So he began repairing these imperfections at no cost. The results impressed him. After fixing the nose of the woman in the car crash, for instance, he reported that she became much sunnier and got along better with guards. On her release from prison, she reunited with her husband and settled down to a stable life, free of drugs and crime. “She regarded the operation as a significant step towards becoming socially acceptable,” Lewison noted.

Eventually he drew up a formal scientific study about his work to determine whether plastic surgery could lower rates of recidivism and keep inmates out of trouble after their release. He published his results in 1965, reporting on 450 operations—mostly nose jobs, although he also reconstructed ears, removed scars, and rebuilt jaws. Over the course of 10 years, 42% of the surgical patients got arrested again after their release and returned to prison. In contrast, 75% of prisoners overall returned to prison—a difference of 33 percentage points. Lewison crowed: the experiment looked like a huge success.

At least on the surface. In the paper, Lewison admitted finding a small but disturbing trend. Some patients, emboldened by their new faces, left behind violent crimes such as robbery only to become scam artists. Their newly handsome faces made people trust them more, and they took full advantage.

More fundamentally, critics noticed several problems with Lewison’s methodology. First, in comparing recidivism rates, he used the general prison population as a control group. But in selecting his surgical patients, Lewison chose only prisoners who had committed five crimes or fewer. In other words, he left out the prisoners who committed the most crimes and were therefore most likely to return to prison. His control group was not a valid one for comparison.

Second, Lewison didn’t account for psychological factors. Many prisoners came from poor, dysfunctional homes and lacked access to medical care. Lewison’s offer to fix their faces, for free, was an act of kindness in lives that had seen far too little of it. Indeed, Lewison’s attention alone—showing he cared—might have motivated them to change their lives all by itself. Similarly, some patients probably felt grateful and wanted to pay the kindness forward by becoming better members of society and avoiding future crimes. Their new faces might have had nothing to do with their improved behavior.

Finally, in addition to seeking surgery, some of Lewison’s patients were improving their lives in other ways. Again, the woman with the battered nose was taking classes and entered drug counseling at Oakalla. So did the surgery change her life, or did those other services? Lewison couldn’t tell. Overall, these flaws seriously undermined his study, making it impossible to conclude whether plastic surgery per se helped keep people out of prison.

To address such problems, a trio of doctors began another, better-designed study in 1966. They selected 663 inmates at Sing Sing prison in New York and divided them into four groups. One group received only plastic surgery. The second received only social services such as vocational training and counseling. The third received both surgery and social services. The last received nothing at all, as a control. Within each group, the doctors also sorted the patients based on whether they had a drug addiction, for an additional variable.

Unfortunately, the results of this experiment were messy. Among prisoners with drug addictions, those receiving both surgery and social services returned to prison at a rate of 50%. Those receiving only surgery returned at a rate of 67%. Those receiving only social services were at 48%. Those who received nothing ended up back in prison at the highest rate of all.

Among prisoners with no addiction problem, those who received surgery and social services returned to prison at a rate of 33%. Those who received only surgery were at 30%. Those who received services alone were at 89%. Those who got nothing were at 56%.

Overall, no clear trends emerge from this data. Surgery apparently did nothing for people with addictions but somehow helped the others a lot. And counseling and vocational training somehow made inmates without drug problems far more likely to wind up back in prison, which doesn’t make sense.

Despite this muddle, the Vancouver and New York studies inspired a slew of others in the decades that followed—in Texas, Virginia, Illinois, England, Ontario—involving thousands more inmates. As before, the surgeons involved mostly fixed noses, ears, and teeth, but they also removed pockmarks, tightened saggy jowls, lipo-sucked love handles, and cinched up baggy eyes. Most of this work was cosmetic, but new noses also helped some prisoners breathe more easily. Understandably, these programs proved wildly popular. A few inmates even refused parole to stick around and get work done.

Enthusiasm ran high among doctors as well. One suggested that plastic surgeons should advise judges at sentencing hearings, especially with teenagers. Surgeons, he proposed, would study the faces of the newly convicted and determine who would benefit most from surgery. Those lucky few would then be sent to hospitals instead of juvenile detention centers.

Of nine studies overall, including those in Vancouver and New York, six found that plastic surgery lowered recidivism rates among prisoners. Two found no effect, and in one study, those who received surgery returned to prison at higher rates. This points to some positive, if modest, effect.

Problems continued to plague these studies, however. In an ethically dicey decision, the state of Virginia began allowing young doctors to practice surgeries on prisoners in 1970—essentially letting rookies make mistakes on a vulnerable population. The practice continued into the 1980s. Methodological issues continued as well. Some prisons used the surgeries as bribes for good behavior. But inmates who behaved well and followed rules were probably more likely to stay out of prison later anyway. Or consider inmates who enrolled in the studies and got their hopes up for surgery, only to receive social services alone—or nothing at all. The pain of yet another rejection might have driven them to lash out by reverting to crime.

Other critics raised points that challenge the very idea that surgery could ever help improve prisoners’ outcomes. Consider a normal-looking adolescent who, for whatever reason, begins committing crimes. In doing so, he’s potentially putting himself in violent situations—situations that can produce scars, broken noses, and other defects. In that case, the physical defects weren’t causing the crimes, the crimes were causing the physical defects. So how would surgery help?

More fundamentally, reentering society is difficult even for those best prepared for it, and the likelihood of returning to prison depends on more than a person’s individual initiative or whether they took classes or received social services. The quality of a person’s support network, their length of time in prison, and their ability to find a stable job and affordable housing are just a few of the factors affecting their chance of success. In the face of these challenges, a crooked nose doesn’t seem all that consequential.

Prisoner-surgery programs ran into other roadblocks in the 1970s. Prisoner rehabilitation in general was falling out of favor, as U.S. and Canadian societies shifted toward a harsher, law-and-order mentality that emphasized punishment. In addition, as word of the programs spread, everyday citizens protested. Some complained about scofflaws getting expensive surgeries for free while law-abiding citizens paid through the nose. Others made moral objections. They saw self-improvement as a function of discipline, hard work, and even suffering. To this mindset, taking a shortcut to goodness, like plastic surgery, was akin to cheating.

Given the methodological problems and wider societal changes, prisoner plastic-surgery programs ceased in the 1980s. Surprisingly, however, the pendulum has recently started swinging back in their direction, for a few reasons.

One is the so-called beauty premium. In short, a robust body of evidence from psychological research shows that being good-looking really does give people a big boost in life. This boost starts young. Handsome schoolchildren receive more attention from teachers and are perceived as smarter and more popular. After graduation, the beautiful ones earn higher salaries and garner more tips, among other benefits.

The beauty premium influences the criminal justice system, too. Attractive folks are less likely to be arrested. They get fined less for minor offenses and receive shorter prison sentences for big ones. They also have an easier time finding jobs after prison. All of which seems to support Edward Lewison’s theories. Give people a new, attractive face, and they should have an easier time in life and stay out of trouble with the law.

Prisons are also, especially in the United States, facing a crisis. The law-and-order mentality of the 1970s has given the United States the highest incarceration rate in the world. As a result, prisons are overcrowded and don’t prepare people to reenter society. Prisons are also growing expensive. In New York City, it costs roughly $560,000—every year—to house an inmate.

Given those problems, and reality of the beauty premium, people are giving Lewison’s ideas another chance. Nonprofits have sprung up in Hawaii, Arizona, and California to help former prisoners fix their faces and receive other services such as tattoo removal. There’s a fiscal case for rehabilitating Lewison’s ideas as well. Even if a state paid surgeons $100,000 per operation, that seems like a bargain compared to keeping someone incarcerated.

We many never know for sure whether Lewison was right that making someone more beautiful can transform their inner life, too. But inside prison or out, we can’t escape the power and lure of beauty.