On January 28, 1969, workers were pulling pipe out of a freshly drilled oil well off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, when a torrent of gassy, gray mud shot out with a deafening roar, showering the men with slime.

Unable to plug the hole, they activated a device that crushed the pipe and sealed off the well. The blowout seemed over—until bubbles of gas started roiling the water nearby. Pressurized oil and gas tapped by the drilling were migrating across the ocean floor, tearing it open and rising to the ocean’s surface.

Oil leaked out at an estimated rate of 210,000 gallons a day, creating a heavy slick across much of the ocean channel. A few days later horrified Santa Barbara residents woke to find their beaches befouled with tar and dotted with dead and dying oil-drenched birds. A reporter came across high-school student Kathy Morales in tears as she watched a convulsing loon.

“This is my life—out here,” Morales cried, as recounted in environmentalist Robert Easton’s book about the spill. “I can’t think of coming down here for a stroll again. I can’t think of some day bringing my children here to watch and to play.”

State and federal officials toured the beach and flew over the channel to view the vast oily sheen. Television stations across the country broadcast footage of the devastation. Residents of the picturesque beach town held noisy protests and demanded a drilling ban; a new activist group urged the public to burn oil-company credit cards and boycott gas stations. The spill “shocked Americans,” writes historian J. Brooks Flippen, “placing environmental protection on the front burner in a way it never had been before, turning a concerned public into an activist one.”

The nation’s newly inaugurated president, Richard Nixon, visited in March, dipping down in a helicopter over the polluted water. Afterward he strolled the beach in his formal suit, toeing at the cleaned-up sand with his shiny black oxfords as his entourage and the press swarmed around.

“What is involved is something much bigger than Santa Barbara,” he told a gaggle of reporters. A hundred yards away a crowd of protesters chanted, “Get oil out! Get oil out!” “What is involved,” Nixon continued, “is the use of our resources of the sea and the land in a more effective way, and with more concern for preserving the beauty and the natural resources that are so important to any kind of society that we want for the future. I don’t think we have paid enough attention to this. . . . We are going to do a better job than we have done in the past,” he promised.

Environmentalists were skeptical of the new president’s assurances. Nixon had almost no record on the environment and had barely mentioned the issue during his campaign. He ran on a platform of law and order and ending the Vietnam War, and vowed to cut back Lyndon Johnson’s social programs. Initially environmentalists’ instincts were sound. Nixon’s administration responded slowly to the spill and rejected calls to cancel offshore-drilling leases.

But Nixon also recognized the huge political power of environmentalism, which blossomed into a popular movement just around the time of his election. He had picked as his top domestic adviser John Ehrlichman, who believed in safeguarding natural resources. Over the next few years Nixon would propose an ambitious and expensive pollution-fighting agenda to Congress, and would go on to create the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and other key elements of the nation’s modern environmental regime.

A “Hysteria” for Reform

In retrospect Nixon is hardly thought of as a nature lover. Reviewing his crucial role in the establishment of the nation’s environmental-protection apparatus induces not admiration but cognitive dissonance.

That’s in part because he is best known for his ruthlessness, a reputation cemented by the events leading to the Watergate scandal that forced his resignation. It’s also because his interests and arguably his greatest achievements lay in foreign affairs; his administration’s domestic initiatives, though substantial, are only dimly remembered. As vice president under Dwight Eisenhower, Nixon had made his name by visiting Asia, Africa, South America, and the Soviet Union, where he engaged in the famous “Kitchen Debate” with Nikita Khrushchev over the relative merits of capitalism and communism. Once elected president, Nixon delegated domestic policy making to his aides and endorsed whatever moves he thought would help him politically.

Furthermore, the environment—a fairly new issue at the time—was only one of many that stirred the public. During his tenure Nixon had to manage the Vietnam War, massive antiwar protests, a hostile counterculture, conflict in the Middle East, inflation, and an energy crisis. He had an “instinctive distrust” of the environmental issue, according to Ehrlichman; he was preoccupied by the high cost of antipollution laws and frequently said boosting employment should take precedence over the environment.

“In a flat choice between smoke and jobs, we’re for jobs,” he once told Ehrlichman. “But just keep me out of trouble on environmental issues.”

Nixon’s eyes glazed over when aides talked environmental policy, but he wasn’t entirely apathetic. He had visited Yosemite National Park and the Grand Canyon as a child and “would lighten up” at mention of parks, according to John Whitaker, his environmental-policy aide. As far back as 1962 Ehrlichman had tutored Nixon on fundamentals of the issue, beginning during a boat trip they took on the Puget Sound. Nixon was also close to his brother Ed, who had studied geology and had environmentalist leanings.

More significantly, Nixon happened to arrive at the White House just as voters rather suddenly began to care deeply about the issue. In 1965 only about a third of Americans surveyed agreed that air and water pollution were serious problems where they lived; by 1967 the figures passed 50%, and in 1970 they reached roughly 70%.

In another poll the percentage of people who named “pollution/ecology” one of the nation’s most important problems soared from 1% in May 1969 to 25% two years later. Membership in the Sierra Club, the nation’s oldest conservation organization, tripled to more than 100,000 between 1965 and 1970.

Politicians, both Democratic and Republican, were falling over themselves to claim the mantle of environmental advocacy. Whitaker later wrote that there was “only one word, hysteria, to describe the Washington mood on the environment issue in the fall of 1969.”

The impulse to make government the protector of nature actually had lofty historical precedents. Nixon himself portrayed his efforts as continuous with those of Theodore Roosevelt, an avid hunter and amateur zoologist who 70 years earlier had made conservation a national priority, placing hundreds of millions of acres of land under federal protection.

Roosevelt’s interest was largely utilitarian, aimed at preventing the extinction of the animals he loved to hunt and promoting sustainable use of forests. But he was also influenced by the naturalist and Sierra Club founder John Muir, who gloried in the beauty and spiritual value of undisturbed nature and championed landscape preservation for its own sake.

In 1903 Muir led Roosevelt on a legendary three-day hike through Yosemite: two outdoorsmen mucking through giant snowdrifts and chatting by the fireside late into the night, with Muir explaining his theory of glaciation and pressing the president to create more protected parklands. Roosevelt adored Muir, calling him “our greatest nature lover and nature writer,” and was persuaded by him to incorporate neighboring land into Yosemite.

But the two men differed on the goals of preservation in ways that would echo down to future administrations. Roosevelt favored a wise-use approach that aimed to preserve woodlands and other resources for future exploitation, while Muir believed in leaving nature pristine. Muir was later devastated by a federally approved dam project that turned Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy Valley into a reservoir to supply water to San Francisco, a dispute some historians say sparked the organized environmental movement.

The American Genius

After World War II the scope of Americans’ conservation concerns broadened as they began worrying about the increasingly visible despoliation of the environment. The baby boom and economic prosperity spurred rapid suburbanization, eating up farmland and open space. Smoke-belching industrial plants proliferated to process raw materials and supply families with mass-produced goods—cars, refrigerators, stereos, air conditioners, toys, processed foods—along with electricity to illuminate their ranch homes and gasoline to power their Chevys and Fords.

At the same time, paid vacation, shorter work weeks, labor-saving devices like washing machines, and a vastly expanded highway system made it easier for suburbanites to visit national parks and to camp and fish. More of them began to see unspoiled wilderness as a picturesque escape and spiritual salve rather than a mere storehouse of lumber and minerals.

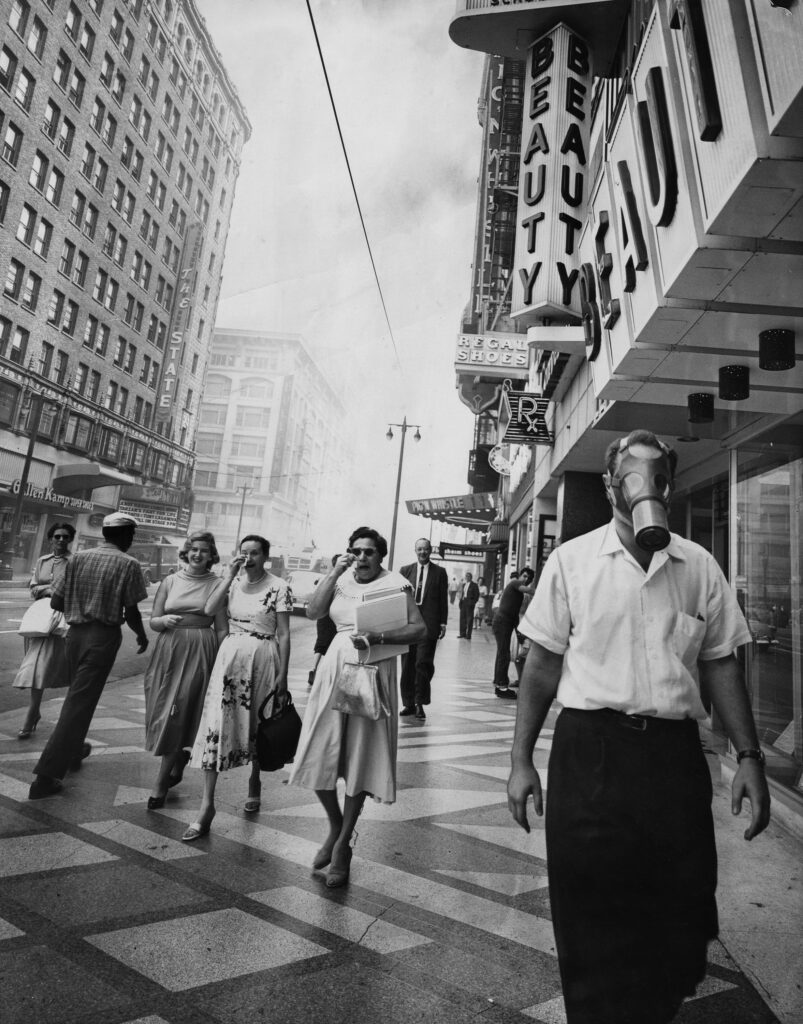

For an increasing number of these people the remarkable progress of the postwar period was accompanied by an underlying worry that the environmental costs of what Nixon called the American “system”—its industrial economy and way of life—were too high. The feeling was aggravated by a series of disasters, such as a notorious smog incident in Donora, Pennsylvania, that killed 20 people in 1948 and inspired the 1955 Air Pollution Control Act, the first such clean-air law. Numerous deadly smog attacks over several years killed hundreds and sickened thousands more in Los Angeles, New York, and other North American cities.

Liberal thinkers, such as economist John Kenneth Galbraith, zeroed in on the detrimental impacts of the consumption economy on the environment and quality of life. In his 1958 best seller, The Affluent Society, Galbraith vividly illustrates the junky scene encountered by a family driving into the countryside.

The family “passes through cities that are badly paved, made hideous by litter, blighted buildings, billboards, and posts for wires that should long since have been put underground,” he wrote. “They picnic . . . by a polluted stream and go on to spend the night at a park which is a menace to public health and morals. Just before dozing off on an air mattress, beneath a nylon tent, amid the stench of decaying refuse, they may reflect vaguely on the curious unevenness of their blessings. Is this, indeed, the American genius?”

The pollution and waste created by industry, automobiles, and throw-away consumerism was creating a crisis, both practical and ethical. The problem in the 1950s and 1960s was “sheer abundance,” wrote Whitaker. By the time Nixon was elected, the nation was pumping out 200 million tons of air pollutants and throwing out 100 million automobile tires and 30 billion glass bottles annually, with much of the refuse piled in mountainous open dumps.

Public concern about the pervasive effects of pollution exploded after Rachel Carson published her hugely popular 1962 book Silent Spring on the dangers of DDT and other pesticides. She made Americans more aware of the synthetic chemicals permeating the environment, the interconnectedness of natural systems, and industry’s failure to address the problem. A few years later the Santa Barbara oil spill flashed across the nation’s TV screens, followed soon after by a famous Time cover showing Ohio’s oozing, intensely polluted Cuyahoga River on fire.

By the late 1960s the burgeoning middle class was discovering that environmental problems threatened their children, their property values, and their lifestyles. Journalist Philip Shabecoff wrote that they worried “about PCBs in mother’s milk, about polybrominated biphenyls in Michigan cattle, about poisons leaking from rusty drums in their backyards, about strontium 90 from atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons.”

Historian Adam Rome argues that scattered apprehension over the environmental toll of the economic boom finally crystallized into a movement thanks to the revitalization of liberalism, the explosion of student radicalism and countercultural protest, and the discontent of middle-class women.

For years these women had been active in conservation campaigns against water pollution, nuclear weapons, and pesticide use. Their sons and daughters, meanwhile, spent their afternoons playing in woods bordering their newly built suburban homes and their nights tossing and turning with Cold War–era visions of nuclear annihilation.

Some of those children grew up to be hippies, who espoused a spiritual appreciation for nature. Many took part in antiwar protests, which inspired a similarly militant environmental movement. Rome also notes the radicalizing effect of individual events, such as the Santa Barbara oil spill, which had spurred college students and other community members to join beach cleanup efforts and demand tougher oil-industry regulations. For Whitaker “the Santa Barbara incident was comparable to tossing a match into a gasoline tank: it exploded into the environmental revolution, and the press fanned the flames to keep the issue burning brightly.”

Politicians had already taken note of this tumult and had begun emphasizing environmental protection in their voter appeals and legislative agenda. President Johnson in particular promoted it aggressively, funding land conservation and signing myriad bills on air pollution, pesticides, water resources, sanitation, solid waste, wilderness, wetlands preservation, endangered species, and highway beautification.

But early antipollution laws accomplished little. They typically called for individual states to set and enforce pollution limits, and state-level policy making was often dominated by business interests and officials who cared more about economic growth than health hazards. Without uniform national rules and federal-level mechanisms to ensure they followed through, states largely ignored the authority granted to them.

Nixon gave little sign of caring about these problems during the 1968 presidential campaign, but he and his advisers soon became acutely aware of their importance. He won an extremely narrow victory over Hubert Humphrey, whose running mate, Maine senator Edmund Muskie, was the congressional leader on environmental issues and a likely future presidential candidate. And so Nixon’s transition staff set up a task force on natural resources and asked Russell Train, a former Republican judge who had helped found the World Wildlife Fund, to head the group.

The task force’s report, presented in December 1968, made an urgent, almost apocalyptic appeal, seeking to focus the attention of a new president who had many pressing issues to address, from the Vietnam War to a weak economy. It recommended the administration give high priority to environmental management, asserting that unchecked pollution would “eventually destroy the fitness of this planet as a place for human life.” Ehrlichman, for one, agreed with the report’s conclusions, ensuring their influence on Nixon’s legislative and policy planning.

Environmental One-Upmanship

Nixon’s environmental agenda was powered by several of his lieutenants, especially Ehrlichman, a political moderate and former land-use lawyer. Ehrlichman had won local acclaim in Seattle for successfully fighting a proposed industrial plant on an island in the Puget Sound, and he coupled his passion for the environment with hard-nosed political instincts. Once in the White House he sold Nixon on the environment, showing him polling data and, Whitaker recalled, making him see it was “politically dangerous if he didn’t get on board.”

Whitaker, meanwhile, was a geologist who combined love for the outdoors with a passion for improving the environment. During a vacation years earlier he read a book about Nixon, became convinced of the young politician’s brilliance, and took leave from his job to work on Nixon’s first presidential campaign in 1960. He had the president’s trust and served as a crucial bridge between environmentalists and the White House.

Outside the White House the greatest influences were Muskie and Democratic senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson of Washington, who competed to propose increasingly stringent environmental regulations and so ratcheted up pressure on Nixon. The president particularly feared Muskie, a charming, plainspoken New Englander who was an early favorite for the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination.

Both senators created problems for the new president. Jackson, chair of the Interior Committee, aimed to coordinate the government’s splintered policy apparatus for handling pollution through a proposed Council on Environmental Quality. Muskie proposed making oil companies fully liable for spills. In a move that particularly bothered the White House, he also called public hearings to investigate the Santa Barbara disaster.

The senators’ energetic agenda rattled Nixon as he sought to set the direction for his young, somewhat unpopular administration. As the oil-spill crisis unfolded, Nixon complained to Ehrlichman about the onslaught of Democratic proposals. This gave Train, Whitaker, and other environmentalists in the administration an opening to call for action, and work began on a package of environmental bills.

Early antipollution laws accomplished little. They typically called for individual states to set and enforce pollution limits, and state-level policy making was often dominated by business interests and officials who cared more about economic growth than health hazards.

In the meantime the administration’s actions reflected Nixon’s ambivalence. On the one hand, interior secretary Walter Hickel, an oil-company ally turned environmental advocate, forced the relocation of a proposed jetport in Florida that would have threatened Everglades National Park. On the other hand, the White House antagonized environmentalists by pushing for construction of an Alaskan oil pipeline and dithering on restricting the use of DDT.

As environmentalists and congressional Democrats continued their attacks, Whitaker and Train argued that the administration was losing on the environment and needed to act more assertively to claim it as a Republican issue. In this charged political atmosphere Nixon signed his first significant environmental bill, the Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1969. The act strengthened the existing law, banning the importation of creatures endangered anywhere in the world and expanding the list of protected animals. The president had little role in the passage of the Democratic measure, but his administration was happy to take the credit, mailing out photos of the signing ceremony. Nixon would follow the same pattern in the years to come.

Soon after, Congress presented him with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which, owing in part to Muskie’s demands, had been greatly expanded from Jackson’s Council on Environmental Quality bill. The bill mandated a detailed report on the environmental impact of all large projects involving federal funding or permitting and, under subsequent court interpretation, allowed the threat of private lawsuits to ensure compliance.

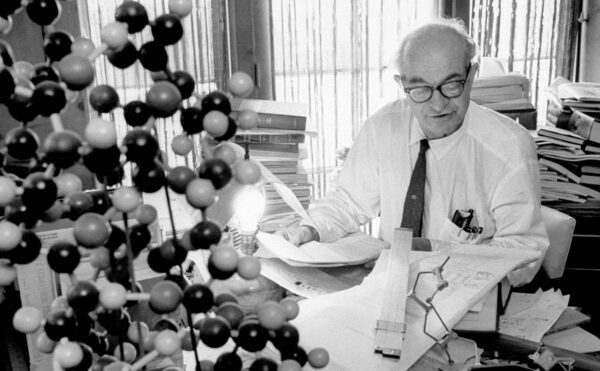

NEPA’s winding path illustrates the key roles Train and other Nixon aides played in making environmental progress despite the president’s qualms. A liberal Republican who had been appointed a U.S. Tax Court judge by Eisenhower, Train developed an interest in conservation during safaris in Africa. He cofounded the African Wildlife Foundation and later headed the Conservation Foundation, where he helped develop the concept of an environmental-impact statement.

So when Jackson and Muskie agreed to a final version of NEPA that required such statements, Train was well positioned to persuade Nixon to reverse his initial opposition. Whitaker, meanwhile, told Nixon a veto would bring a congressional override and “court political disaster” just as the president was preparing for an environmental-policy offensive. So Nixon again embraced a bill he had done little to shape, signing it on January 1, 1970, and, according to Flippen, portraying it as “a demonstration of his personal concern for environmental quality” as the new decade began.

While Train and Whitaker helped push the bill through, neither they nor anyone else in the White House foresaw the mandate’s immense consequences. Environmental groups would soon begin suing to enforce the impact-statement requirement, holding up the licensing of nuclear-power plants, oil drilling on the outer continental shelf, and construction of the Alaskan pipeline.

Presidential Leadership at Last

As Nixon promised, the first few years of the 1970s were a golden period for environmental action. He kicked off the decade with a State of the Union speech that gave unprecedented attention to the environment, calling for a policy of “balanced” national growth, more parkland, and regulations to control air and water pollution. “Restoring nature to its natural state is a cause beyond party and beyond factions. It has become a common cause of all the people of this country,” he said.

Muskie, Jackson, and other Democrats sniffed at the address, saying the president was all talk and little action. But Nixon followed up with a lengthy February speech to Congress expressly on the issue, addressing water pollution, municipal waste, and industrial pollution. He proposed new auto-emission rules, the spending of billions of dollars on sewage-treatment plants, and a reorganization of government to end piecemeal policy implementation.

“The tasks that need doing . . . call for fundamentally new philosophies of land, air, and water use, for stricter regulation, for expanded government action, for greater citizen involvement, and for new programs to ensure that government, industry, and individuals all are called on to do their share of the job and to pay their share of the cost,” Nixon said.

He left out a few contentious issues, such as DDT and the Alaskan pipeline, but at least initially the administration’s claim to environmental leadership was a raging success. The Sierra Club and other environmental groups showered Nixon with praise. CBS newsman Roger Mudd asked Muskie, “Has the president preempted the environmental issue?” Mudd’s colleague Dan Rather quipped, “What it boils down to is that the president has caught the Democrats bathing, and he’s walked away with their clothes.”

In the months that followed, Nixon signed two more significant bills: one created a commission on national population growth; the other, Muskie’s Water Quality Improvement Act, made oil companies fully liable for spills rather than partly liable, as the administration would have preferred.

As the first Earth Day approached on April 22, 1970, Hickel urged the administration to build on its momentum by declaring the day a national holiday. He saw environmentalism as rare common ground with a counterculture roiling the nation with its rejection of mainstream social norms and demands for women’s rights, civil rights, and an end to the war. But the youthful, leftist organizers of Earth Day dismissed the administration’s environmental efforts as a “billow of smog” and rejected Ehrlichman’s request for a meeting.

Twenty million Americans participated in the festivities, rallies, protests, and teach-ins of Earth Day. Hickel, Train, and some other officials gave speeches at universities, but Nixon stayed quiet, declining to endorse an event with anti-administration overtones. Eight days later he announced the invasion of Cambodia, spurring massive campus protests. National Guard troops opened fire on protesters at Kent State University in Ohio, killing four and shocking the nation. Student demonstrations soon shut down hundreds of campuses across the country.

For Nixon these were among the darkest days of his presidency. Dejected and agitated, he responded impulsively with an unscheduled 5:00 a.m. visit to a protest at the Lincoln Memorial. Exhausted, with bags under his eyes, he spoke to a few baffled students, rambling about football, foreign policy, and the search for meaning in life. “I just wanted to be sure that all of them realized that ending the war, and cleaning up the streets and the air and the water, was not going to solve spiritual hunger, which all of us have,” Nixon wrote in his diary.

Nixon had actually done well with young voters during the election, but Hickel said his hopes for improved youth outreach were “crushed” after the Cambodia decision and Kent State incident. In a letter he told the president that young people, now “unable to communicate with either party . . . are apparently heading down the road to anarchy.” American history, he wrote, “clearly shows that youth in its protest must be heard.” The letter was leaked to the press, and the outraged president eventually forced Hickel to resign, depriving the administration of one of its leading environmentalist voices.

“All Politics Is a Fad”

However passionate others were about environmental action, to Nixon it remained just one more political demand to juggle. At a 1970 White House meeting with leading environmentalists, he began by lecturing them: “All politics is a fad. Your fad is going right now. Get what you can, and here’s what I can get you.”

When it was Sierra Club president Phillip Berry’s turn to speak, he exploded, telling Nixon, “I don’t believe what you believe in.” The two argued for five minutes, and Nixon angrily adjourned the meeting.

Berry thought the president wasn’t convinced of environmentalists’ political strength, but Nixon and his aides were actually impressed by the fervor of this new social movement. “Who is this Sierra Club?” asked an incredulous Henry Kissinger, the secretary of state, after the exchange.

Later that year Nixon created the EPA, one of his greatest environmental achievements, which came about largely because it related to a goal he actually cared about: shrinking the federal government. Working through a reorganization plan rather than legislation, he consolidated functions scattered among some 44 government offices. The EPA would treat “air pollution, water pollution, and solid wastes as different forms of a single problem,” Nixon said. Pleased by the idea of unified antipollution leadership, House and Senate subcommittees agreed to the new regulatory agency.

Yet the president’s basic apathy about the environment produced a split personality in administrative policy. For example, a perceived need for more residential construction, along with timber-industry lobbying, led the White House to back more tree cutting on public lands despite strident opposition and lawsuits from environmental groups.

The administration likewise maintained a piecemeal approach to DDT restrictions, banning the treatment of fruits, vegetables, and forest trees but not cotton crops, which accounted for almost 75% of the pesticide used. The federal government also failed to address the effects of strip mining for coal in Kentucky and West Virginia, which, writes Flippen, “turned lush landscapes into permanent pits, polluted the air with sulfuric acid from oxidized coal, and contaminated streams with chemical-laden overburden.”

Environmental advocates had to battle not only Nixon’s covert indifference but also the administration’s preoccupation with other problems that seemed to worry voters at least as much.

The president’s basic apathy about the environment produced a split personality in administrative policy.

The postwar boom was winding down; the economy was stuck in a nasty combination of rising unemployment and increasing living expenses that pundits labeled “stagflation.” Residents of hard-hit industrial towns, such as Bristol, Connecticut, struggled to find jobs. “It’s hard to get by,” a laid-off carpenter named George Worthley told the New York Times in August 1970. “I used to work seven days a week, but now it’s impossible to find anything at all.”

The Republicans’ political prospects were considered poor in the upcoming midterm elections. Whitaker and others were desperate to show some kind of progress on environmental issues that might boost support for the president’s party or at least stem potential election losses. So when Congress passed a $400 million measure to build recycling and trash-disposal facilities, Nixon once more swallowed his objections to the high cost and fear of federal overreach and signed the bill. He also gave a nod to outrage over the Santa Barbara oil spill, formally rescinding a set of suspended drilling leases there.

A Triumph for Cleaner Air

These steps may have kept the administration from seeming outright hostile to environmental concerns, but they were not enough to turn the tide in favor of Republicans, who lost seats in Congress as well as several governorships. Nixon felt he had no choice but to work for environmental and other domestic policy achievements that would win over the public or at least stave off a further decline in support. A reelection battle, likely against Muskie, also loomed.

Both Nixon and Muskie had been sternly criticized by activist Ralph Nader. In a May 1970 report on the country’s ineffective air-pollution laws, a Nader-supported task force said that “each in his own way offered more of the same palliatives which have failed the nation over the last several years.” In big cities and industrial towns Americans moved through a gray haze, thick with sulfur dioxide and ozone smog. A New Yorker “almost always senses a slight discomfort in breathing, especially in midtown,” the report said. “He periodically runs his handkerchief across his face and notes the fine black soot that has fallen on him.”

A bill endorsed by the White House promised to finally fix the problem. The EPA would set standards for outdoor air quality and the amount of pollution individual industries might emit, with deadlines for compliance. The measure would establish enforceable emission standards for new cars and would empower the EPA to run pollution-control programs in states that didn’t do so themselves.

Rather than allow Nixon this achievement, Muskie, who had been stung by Nader’s earlier criticism, juiced up the bill with mandates requiring quick and unrealistically high reductions in auto emissions. The measure required carmakers to use pollution-control technology that did not yet exist. Whitaker and other aides urged Nixon to accept the bill nonetheless, arguing that a veto would inevitably result in an override by a Congress eager to fix the terrible air quality plaguing major cities. The bill’s flaws could be addressed later.

It took much convincing by his aides, but Nixon finally held an elaborate ceremony and signed the Clean Air Act of 1970 into law—without inviting Muskie to attend or even mentioning his name, despite his central role in the bill’s passage. Over the next half-century the law and further amendments would help reduce by nearly 70% the total emissions of six major pollutants—carbon monoxide, lead, ground-level ozone, nitrogen dioxide, particulate matter, and sulfur dioxide—even as the U.S. population continued to climb and the country’s economy expanded.

Nixon also made other moves environmentalists favored, such as permanently stopping construction of the controversial Cross Florida Barge Canal, which had already sliced partway across the Florida peninsula and would have decimated wildlife in the Ocklawaha River ecosystem. In his second environmental address he proposed greater EPA authority over pesticide regulation, more money for sewage-treatment centers, and funding for states to develop environmentally friendly land-use programs.

Nixon had gone from barely caring about natural resources to making their protection a major federal responsibility. “In spite of his program’s incompleteness, he arguably had done more in two years than any president in history,” Flippen writes, placing him in the same league as Theodore Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson.

Nonetheless, the Republicans had been spanked in the midterms, losing House seats and governorships, and Nixon’s approval ratings fell below 50% for the first time. Voters still cared about pollution, approving environmental measures in 13 states, but economic worries and anger over the Cambodia invasion swamped other issues. To Nixon it seemed that environmentalists could never be satisfied: Muskie had accused him of launching a “sham attack on pollution” and said the expensive sewage-treatment plan was still too small, while critics dismissed White House proposals on ocean dumping and land use as insufficient.

Whitaker remained characteristically optimistic, counseling yet another environmental offensive, a coordinated “game plan” of TV interviews by White House aides and lunch meetings with congressional staffers. But despite his advisers’ cajoling Nixon was losing his taste for hopeful concession on domestic matters. “The environment is not a good political issue,” he told his chief of staff H. R. Haldeman. “I have an uneasy feeling that perhaps we are doing too much. . . . We’re catering to the left in all this.” He began moving away from the relatively liberal Republican model of the past two years and, in private, let loose the angry, cutthroat, demagogic Nixon that is his legacy.

At a private meeting with CBS television executives in March 1971, he told them he “had no sympathy with environmentalists” who demanded TV airtime. At a moment when a new generation of direct-action groups such as Greenpeace was gaining prominence, he scorned the environmentalist vision of deemphasizing economic growth and living in better harmony with nature: “Some people want to go back in time when men lived primitively . . . really a very unhappy existence for people,” he told the executives.

On another occasion he told leaders of the Ford Motor Company that environmentalists and consumer advocates wanted Americans to “go back and live like a bunch of damned animals. They’re a group of people that aren’t really one damn bit interested in safety or clean air. What they’re interested in is destroying the system.” In public, though, he remained positive on the environment.

The Global Dividend

Once Nixon lost interest in pursuing the environmental vote, Train, Whitaker, and EPA chief William Ruckelshaus found themselves increasingly ignored. Meanwhile, commerce secretary Maurice Stans, a proud enemy of environmentalism, was emboldened to openly disparage EPA programs.

Politically speaking, Nixon was wise to toughen up his public persona. The populist president—against tax hikes, for business interests, against desegregation busing—“hit a chord with the public,” according to Flippen. He also scored a huge diplomatic triumph: Americans were amazed when Nixon visited one of the nation’s greatest foes, Communist China, with a view to normalizing relations. This would speed the end of the Vietnam War, they hoped, and pressure the much-feared Soviet Union into détente. Nixon’s popularity rose, and polls late in 1971 put him ahead of Muskie for the election, reversing the trend of the previous year.

The administration didn’t completely abandon the environment, but other priorities took precedence, including worries about oil and natural-gas shortages. Bills were passed exempting the Alaskan pipeline from NEPA’s review requirements and allowing the temporary licensing of nuclear power plants without environmental impact statements. The influence of big corporations on federal policy was evident, for example, in an agreement Nixon signed with Canada to improve water quality in the Great Lakes. He agreed to address the dumping of dredging spoils and phosphates from detergents that had fouled the water and caused a giant algae bloom, but pressure from detergent manufacturers weakened the water-quality standards.

Train and Whitaker did retain a little influence, and Ruckelshaus made good use of his powers as EPA administrator. And on the international level environmentalism remained strategically useful.

The U.N. Conference on the Human Environment, held in June 1972, was a success for the administration. Ruckelshaus announced the phaseout of all domestic uses of DDT (although Nixon was furious and wanted the decision reversed), and delegates adopted a number of American proposals, including a moratorium on whale hunting, the creation of a fund to support environmental programs around the world, and an agreement to limit the dumping of waste from ships, planes, and man-made platforms into oceans. Another top Nixon goal—to advance détente with the Soviets—also succeeded, with Train negotiating an exchange of environmental research and information.

The Final Retrenchment

Coming out of the 1972 Republican convention, Nixon was in good shape. He gloried in his diplomatic triumphs after making legendary trips to China and the Soviet Union. His Vietnam strategy, massive bombing while calling for a cease-fire, was politically sustainable; the economy had improved; and Muskie’s presidential bid had collapsed. The campaign of the Democratic nominee, Senator George McGovern, was a disaster. Meanwhile, five men had been arrested on June 17 at the Watergate office complex in Washington while apparently trying to bug the Democratic National Committee, but the incident received little attention.

Polls showed that Nixon would beat McGovern easily, but the environment remained such a politically popular issue and Congress so eager to respond to voters’ concerns that the administration felt compelled to pretend the president still cared. Nixon’s wife attended the centennial celebration of the National Park Service at Yellowstone, even as the president complained privately that wilderness areas “are only for rich backpackers who have several weeks’ vacation.”

And when several pieces of long-awaited environmental legislation finally came his way, including measures on pesticides and protection of marine mammals, he signed them—except for one.

The most important bill of the lot was the most contentious. The Water Pollution Control Act Amendments would regulate single-point sources of pollution, such as factories and military bases; establish standards for pollution-control technology and for water quality in lakes and rivers; and help finance municipal sewage-treatment plants.

Nixon had proposed such a law, but he vetoed Congress’s final version, citing the $24 billion price tag. The next day the House and Senate overrode the veto. The news was soon overtaken by Kissinger’s surprise announcement that a Vietnamese peace accord was nearly concluded.

Two weeks later Nixon was reelected in a landslide. Emboldened by the success of his populist agenda, he renewed his efforts to shrink the federal government and reduce spending. In a sign of how far he had retreated from his old aim of outgunning the Democrats on the environment, Nixon ordered the EPA to spend only $9 billion on sewage plants, half the amount authorized.

The affected towns and states were outraged. Past presidents had similarly impounded budgeted funds, but Nixon would be the last to do so. The House considered impeaching him, and the following year a federal court ordered the full allocation released. In 1974 Congress passed the Impoundment Control Act, making it clear the president could not refuse to spend appropriated monies.

Nixon’s retreat on the environment accelerated as he began his doomed second term. Whitaker was demoted to undersecretary of the interior, and an advocate for farmers, Earl Butz, was made the president’s natural-resources counselor. “There are many more important things than the environment,” Butz wrote in a subsequent policy paper. The outspoken Ruckelshaus was transferred from the EPA to the FBI, and Train was made the EPA chief, which ensured continued strong leadership at the agency but removed a consistently pro−environment policy voice from the White House.

In his third and final environmental address to Congress in February 1973, Nixon declared the environmental crisis over. “I can report to Congress that we are well on our way to winning the war with environmental degradation, well on our way to making peace with nature,” he said. He stressed a balance between economic growth and environmental protection, and said states and the marketplace should bear the costs of protection, not the federal government.

The remaining environmentalists in the administration found themselves all but ignored. The United States reneged on its agreement with Canada to clean up the Great Lakes and fell behind schedule in proposing new wilderness areas. The administration approved an increase in timber harvesting from national forests and rejected a request from environmental leaders to meet with the president.

In October 1973, after the United States resupplied Israel with weapons in the Yom Kippur War, Arab countries imposed an oil embargo on the United States, setting off a national energy crisis. With the Watergate scandal worsening and Nixon’s approval ratings bottoming out, the president seized the opportunity to propose a series of environmentally hostile responses to the crisis, such as increasing outer−continental shelf oil drilling and temporarily exempting power plants from some clean-air regulations. Congress quickly passed and Nixon signed a bill that finally cleared all barriers to construction of the Alaskan pipeline. The administration even looked for a way to allow oil drilling to resume in parts of the Santa Barbara Channel, where four years earlier Nixon had seen up close the political power of the environmental movement.

Congress did pass one more important pro-environment bill, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, which added protection for “threatened” species and allowed federal jurisdiction over critical habitats. As usual Nixon was worried about the law’s cost but signed it anyway. In the new year he didn’t even bother making an environmental address; rather, the administration focused wholly on the energy crisis, pushing for bills that would stifle improvements in air quality. One measure would delay deadlines on auto emission–control technology and another encouraged power plants to switch from oil to coal, a dirtier but cheaper fuel.

In July 1974 the House of Representatives began its impeachment debate. Nixon’s time in office was nearly over, and characteristically, he went out with a snarl against environmentalism. In a televised speech on inflation he once more made a point of prioritizing economic goals over “certain other objectives that are worthwhile, such as improving the environment and increasing safety.” He also vetoed the EPA’s budget, calling it excessive. And then he was gone.

A Legacy of Consensus and Polarization

Despite his personal indifference to pollution problems and his antipathy toward the antigrowth philosophies of many hard-core environmentalists, Nixon left a huge mark. He had agreed to reshape government and society around the need to restore and protect the environment, even to the point of creating NEPA and the EPA, which impinged on his own economic-development goals. His political expediency ultimately led to lasting, material improvements to air, water, and land.

“By the mid-1970s progress could be seen clearly, and an environmental ethic had become embedded in the national being,” Whitaker wrote in 1976. “Protecting the environment had become institutionalized in federal, state, and local governments and in the judicial system.”

Nixon himself gave little thought to his environmental legacy after he left office. In several books he recounted his election battles and diplomatic successes but never mentioned the environment in his writing or speeches. Years later, when Whitaker told Nixon he would be remembered for his domestic-policy successes, especially on the environment, Nixon responded, “For God’s sake, John, I hope that’s not true.”

In the succeeding years environmental politics matured and grew more rigid. The excitement of the first Earth Day faded; activism shifted from getting transformative laws passed to influencing the crucial but plodding details of EPA administrative decisions and rule implementation. Antiregulatory business groups became more sophisticated and helped make skepticism of environmentalism and its costs a Republican platform plank.

Years later, when Whitaker told Nixon he would be remembered for his domestic-policy successes, especially on the environment, Nixon responded, “For God’s sake, John, I hope that’s not true.”

During his presidency in the 1980s Ronald Reagan moved forcefully to roll back regulations, installing openly anti-environmental officials at the EPA and Department of Interior, which provoked a bitter backlash. The environment became a flashpoint for political opposition, as shown in the fierce legal and congressional battles over regulating greenhouse gases during the Obama administration. More recently, the Trump administration appointed long time EPA foe Scott Pruitt as the agency’s administrator.

In a 2016 interview Flippen noted the irony that the effort to regulate carbon dioxide emissions depends on a body of regulations first established under Nixon. “I enjoy looking at Nixon as sort of a window into the politics of the age,” Flippen said. “This is a Republican president, and what he did on so many domestic issues would be considered far-left today. In just 40 or 50 years, things have changed so dramatically. You can really tell someone’s party allegiance by their position on the environment. You can ask, do you believe that humans caused climate change? If you say yes, you’re a Democrat. And if you say no, it’s even stronger—you’re a Republican.”