When I tell my boyfriend I am going to Harry’s World, he assumes I am out for blood.

Harry’s is Philadelphia’s premier occult store—a small place on South Street sandwiched between a smoke shop and a custom t-shirt outfitter. From the outside, it looks oddly like a deli, but the faded yin-yang symbol on the sign hints at what’s within.

It was preceded by Harry’s Occult Shop, originally founded in 1917 as a pharmacy by Harry Seligman, who switched his business to the supernatural in response to a growing demand from his predominantly Black clientele, many of whom had migrated to Philadelphia from the South and were seeking ingredients for potions and folk remedies.

Over the years the store has been the source of much speculation and many newspaper columns. In 1971, a reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer found the place so off-putting that he walked out without speaking to anyone. In 1982, another writer reported that the store sold roughly four human skulls a year for as a little as $134, although the price could climb depending on how many teeth were left inside the skull. A wolf’s eye ran you $22.25 a pop. The customer base at the time was made of up of “very religious people [who are] scared of outside things; things that they believe will harm them,” said Bob Seligman, Harry’s nephew and then-manager of the shop. “Most of them are nice people, but some of them are vengeful.”

The store was passed down more or less through Seligman’s family, eventually moving a few doors down from the original location. About 10 years ago the landlord took it over. Harry’s World is its current incarnation: a small, cozy place that smells of incense, packed with candles, crystals, enchanted bubble bath, and a large white cat named Snowball who lost an eye in a street fight.

My boyfriend lived for 16 years in West Philly, where many of the city’s self-styled witches are concentrated. He warns me that if I write something mean about Harry’s, I will get myself hexed. “We don’t need any hexes in this house,” he says, only half joking.

I keep this in mind as I walk over, but I have no intention of messing with the store. I’m interested in its spiritual oils—a motley assortment of small vials that promise love, luck, money, assistance in court cases, and relief from hexes. One confusing bottle promises to help customers stay at home; another simply reads, “Destroy Everything.”

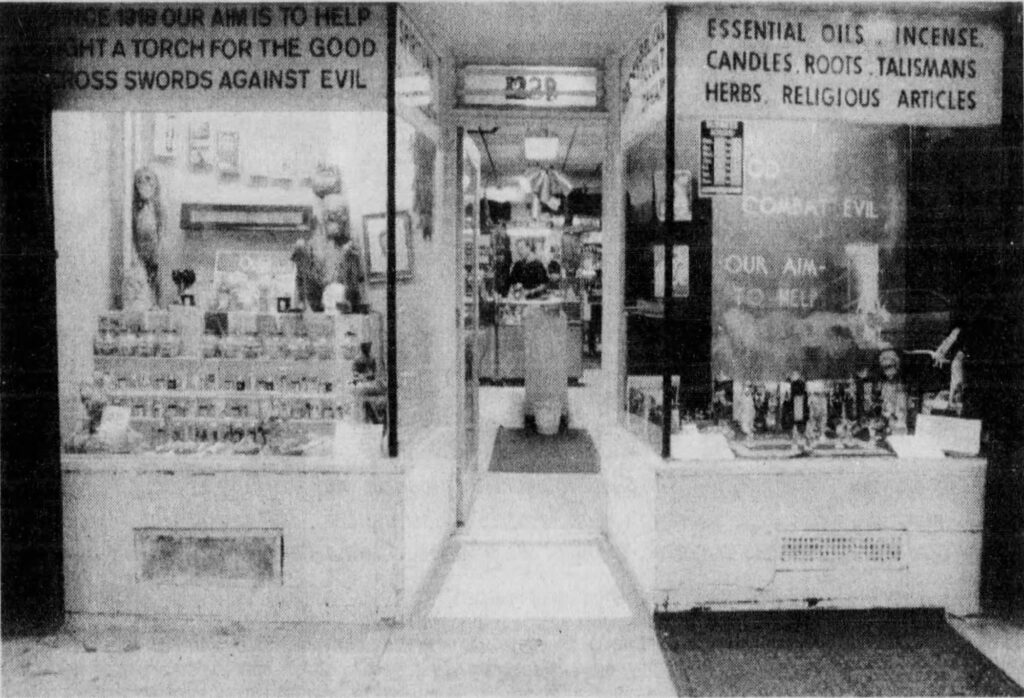

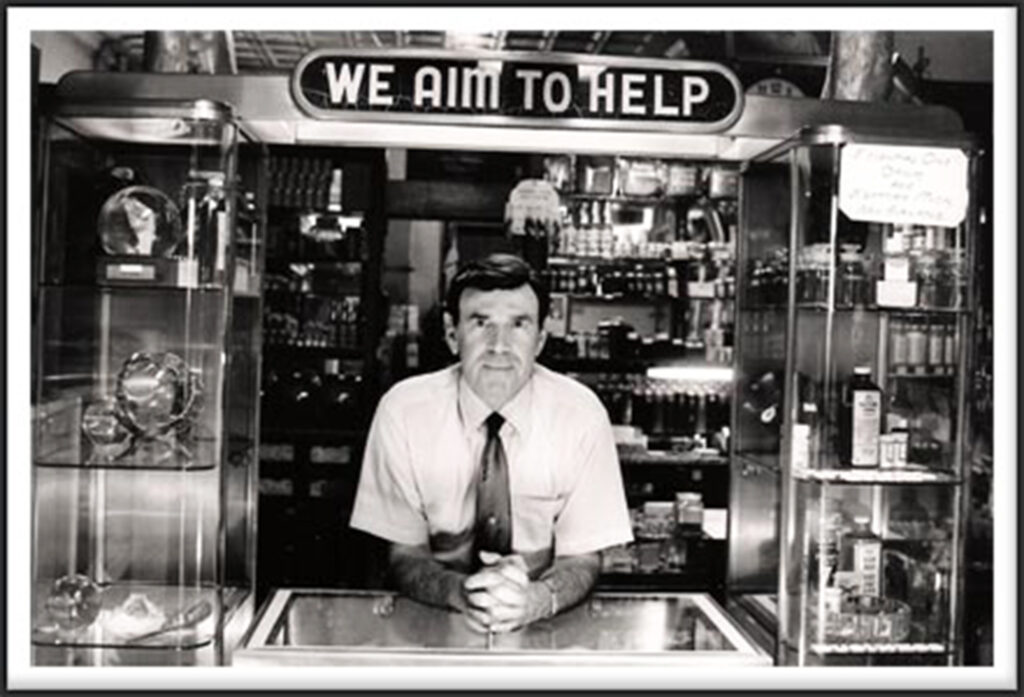

Counterclockwise from top, Exterior of Harry’s Occult Shop, 1993; interior of Harry’s Occult Shop, date unknown; exterior of Harry’s World, 2023.

Philadelphia Inquirer; Internet Archive; Rebecca McCarthy

Some of these oils are sourced externally, but the store’s staples are mixed in house. Jim “Raven” Stefanowicz, founder and high priest of the South Street Circle, a neo-pagan ritual group, worked at Harry’s World from 2016 to 2020 as a tarot reader and alchemist.

“During my first week there, I noticed that many of the ‘oils’ being sold were merely alcohol-based perfumes,” Stefanowicz told me over email. “Don’t get me wrong, there is deep magic in aromatherapy, and fragrances hold the power to evoke memories and trigger shifts in consciousness conducive to overall wellness. However, as I was hoping to drench the store in ‘old world magic,’ I formulated new, natural blends inspired by those in my own ‘Book of Shadows.’ ”

Stefanowicz’s family roots in the city stretch back at least 100 years to an area below Oregon Avenue once known as The Neck—a swamp anchored by pig farms and shanty houses. “A curious thing about Philadelphia is that pigs were permitted to be kept in the thickly settled parts of the city until quite recently,” wrote Edith Elmer Wood in her 1919 book, The Housing of the Unskilled Wage Earner: America’s Next Problem. “A start was made to do away with this condition, the 40,000 piggeries of a few years ago having been reduced to about 10,000 by the spring of 1917, when the Health Department at last decreed that all must go.” The resulting “war on piggeries” culminated in a number of raids and violent stand-offs between the pig farmers and police, but ultimately the pigs were cleared and the swamps drained to build a football stadium.

Mystical goods sold at Harry’s World, 2023.

Rebecca McCarthy

I am so impressed by this pedigree that when Stefanowicz tells me he met the Norse god Odin in Girard Park a few years ago, I’m inclined to believe him. During his tenure at Harry’s he waited on everyone from bishops to sex workers, who came to him to remove hexes, investigate hauntings, alleviate infertility issues, and address all manner of other problems. Today he runs his own practice, but magical essential oil blends are still among his best-selling products.

Browsing the Inquirer archives, you can see why. People are frightened, they are jealous, they are vengeful, they are sad. They want their kids to be happy, they want their parking tickets resolved, they want their cousin to stop violating his probation, they desperately want to fall in love. Revenue from essential oil sales increased 40% from 2014 to 2018 within the United States, due in large part to the meteoric rise of the wellness industrial complex, which promoted a kind of magical thinking around the idea of health and self-care. These companies managed to co-opt legitimate health fears and repackage them in a self-serving way—all manner of illness could be cured through expensive “natural” remedies, impurities could be flushed out through positive thinking, and ill health became quietly synonymous with poor character.

Wish fulfillment has always been a big business, and essential oils, with their promises to cure what ails you both physically and psychologically, are some of the industry’s oldest tools of the trade.

So is there anything to all this hype, scientifically? Do these oils do any of the things that they’re advertised to do? It largely depends on how you’re using them.

Essential oils are generally produced through steam distillation and are composed of hundreds of different chemicals. The same species of plant can produce different chemical varieties depending on the conditions in which it grows; climate, soil conditions, and even the method of fertilization can affect the compounds produced. This is why standardizing a specific smell or flavoring (mint toothpaste, for example) is so difficult and requires extensive chemical analysis.

Hydrocarbon compounds called terpenes make up most of the chemicals found in essential oils. Although they’re often spoken about interchangeably, terpenoids are terpenes that have been manipulated chemically—either naturally or synthetically. There are tens of thousands of terpenoids, and scientists are discovering more every day. Monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes produce the unique smells of essential oils and protect plants from pests and disease, but plants use these chemicals in other ways as well.

“Plants can’t move, they’re sessile,” said Abby Bryson, a doctoral candidate in molecular plant sciences at Michigan State University. “So they have to interact with their environment through chemicals instead of physically.”

Terpenoids have benefits for humans too, although they don’t function in the way essential oil sellers often say they do. Paclitaxel, a drug used to treat lung, breast, and ovarian cancer, is derived from a terpenoid, as is artemisinin, a common antimalarial drug.

Scientists are currently studying terpenoids for their antimicrobial properties. Essential oils are lipophilic, which means they’re able to dissolve into fats and other oils, and thus can penetrate bacteria’s cellular membrane and disrupt basic functions, such as nutrient processing and cellular reproduction. They have a similar effect on viral and fungal cells, where they can enter mitochondria and disrupt the source of energy.

The World Health Organization has named antibiotic resistance one of the most significant threats to humanity, and industrial agriculture is largely to blame, consuming roughly 80% of the antibiotics used in the United States. Farmers pump livestock full of the drugs to prevent—rather than resolve—disease and to increase the size of their animals. As result, bacteria and viruses have ample opportunity to adapt and grow resistance—producing superbugs that threaten both livestock and human populations. While essential oils are not a silver bullet and there are many hurdles to overcome, using them on livestock in place of antibiotics could mitigate the effects of rapid viral evolution. A 2017 report from the Pew Foundation outlining alternatives to industrial antibiotic use found essential oils showed promising results in cattle, pigs, chickens, and turkeys, although the concentrations required were so high that meat quality was the worse for it.

“Dilapidated old South st., stomping ground of the weary and distressed, quietly has become the commercial center of Philadelphia’s ‘mystic powers’ scene,” Jonathan Takiff wrote for the Philadelphia Daily News just before Halloween in 1972. The Harry’s he describes is bustling, “the salesladies displaying the friendly confidence of a family physician as they prescribe the house specialties.”

It’s a bit of a depressing read, given the current scene. South Street is in better shape, but it’s still punctuated by empty storefronts, and Harry’s is all but deserted when I visit—although admittedly I am there at 3:00 p.m. in the middle of the week. The only customer I meet is a woman buying Florida Water, which she uses as a bathroom spray—not for any spiritual purpose. She just likes the smell.

I was hoping for a little more grist, I guess, someone with a specific problem they’d come in looking to solve with a potion, but maybe I should count myself lucky. In a 1991 piece for the Inquirer, Steve Lopez describes a customer looking to exact revenge on her husband, who had recently left her.

“I just want him to feel what I felt,” she announces upon entering the store. “He’s gone. I don’t want him to be happy.” According to Lopez, she “wears a long coat, speaks sparingly, and reveals little about herself.” She is threatening enough, though, that he has “a premonition that more information might be available some day in a Metro Brief.”

Bob Seligman suggests she purchase Turn-it-Back oil and powder, used to throw negative energy back to its sender. This is rejected as impossible, as the spell must be administered through the recipient’s shoes, to which she no longer has access. The woman ultimately buys ingredients for a spell called Mistletoe, meant to return to the spellcaster someone who has deserted them.

There’s always something a bit menacing about the wish fulfillment business, although Harry’s has tried to discourage people from using black magic—to this day its motto remains “We Aim to Help.” For all their real and imagined powers, essential oils have a long history of straddling the lines between medicine, magic, and scam.

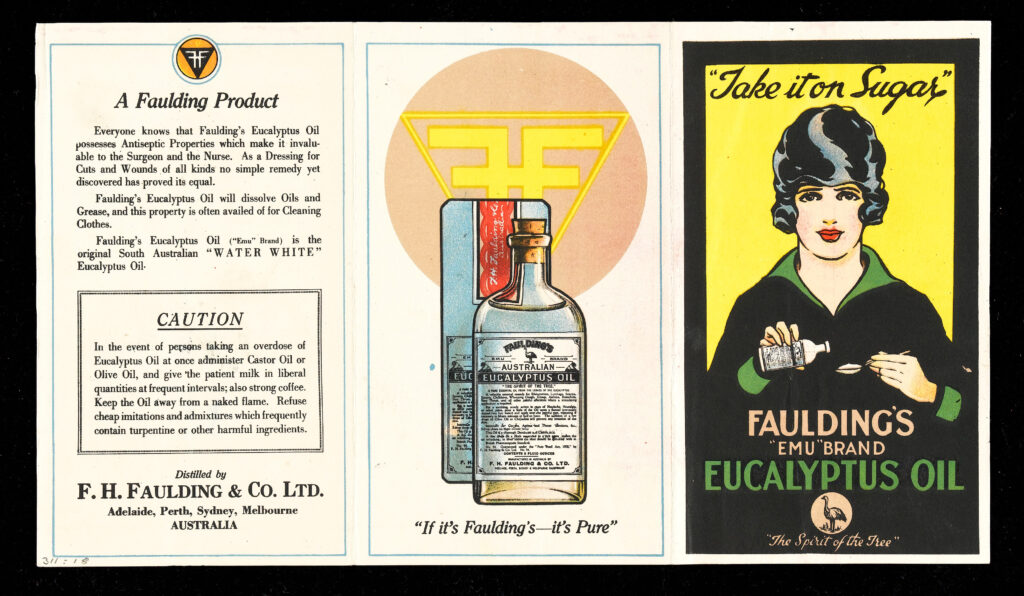

Ancient Egyptians used them in cosmetics, ointments, and funeral proceedings as early as 4500 BCE, and they appear in Chinese and Indian medicinal records around 3000 and 2000 BCE, respectively. Australian aborigines historically used tea tree oil to treat colds, skin infections, and other afflictions.

They became commercially widespread in Europe in the 16th century alongside the patent medicine industry and the quacks who sold them. The term quack doctor is derived from the Dutch kwakzalver, or “hawker of salves.” Quacks and the nostrums they peddled filled a void in care for poor and working-class communities often neglected by physicians. Eighteenth-century Scottish doctor William Buchan attributed their proliferation to the secrecy around medical knowledge at the time.

“Had physicians never affected mystery, quacks and quackery could never have existed,” he wrote in his 1769 book, Domestic Medicine. “Now that they have over-run all Europe, and disgraced both nature and the medical profession, there is no other method of discrediting them with the people, but a total reverse of behaviour in the Faculty.”

As scientific and medical institutions pushed back against dubious herbal remedies, herbalists fought back with propaganda. The fight spanned centuries, as evidenced in Dragged to the Light!, a pamphlet published by herbalists in 1905 that pushes anti-vax sentiments and includes chapter titles such as “Analysis of Your Hypocrisy and Cowardice,” “Crushing Evidence,” and “How Dr. Walsh Killed His God.”

Essential oils and quack remedies traveled to the United States with the colonists, distributed through a network of itinerant peddlers who walked dusty backroads for months at a time dragging suitcases packed with glass vials from town to town.

“Many of them were incompetent for any other sort of work—queer characters, born vagabonds, commercial Ishmaelites, for whom the highway held an irresistible fascination,” wrote Richardson Wright in Hawkers and Walkers in Early America (1927). “They evidently lived on hand-outs and slept in barns. No one ever heard of their retiring rich.”

The essence peddler occupied a strange space in society and its cultural imagination—both merchant and vagrant—and many townspeople viewed their periodic arrivals with ambivalence. Peddlers generally came from New York and New England, toting trinkets, tools, and strange remedies to towns across the South and along the western frontier. They were ragged, but oddly urbane; largely uneducated, but in possession of peculiar politics.

Mint oil became especially popular in the late 18th century, giving rise to a series of sometimes warring “peppermint kings,” the first of whom was an ardent abolitionist who heavily influenced the politics of the peddlers who bought from him. These men, in turn, gained a reputation for being radical and somewhat shifty.

“I have ribbons and chintzes, red, purple, and green, / Which will make your sweet daughter a neat little queen,” a traveling salesman says to a guileless customer in the folk ballad “Essence Peddler,” and “laughs into his sleeve” after making the sale. The song concludes,

It is high time to know how the crooked world goes;

Leave gouty old uncles, and croaking old aunts,

And go peddle Essence—good Lord, what a chance

For a little money!

Germ theory didn’t come to dominate medicine until the late 19th century; prior to that the field was prevailed over by doctors known as “regulars,” who practiced humoral medicine.

Medieval in its brutality, humoral medicine was based on the 2,000-year-old theories of Hippocrates, who believed illness was caused by the four humors—blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile—falling out of balance. An excess of blood, they believed, would cause fevers and sweating, thus the patient would be bled until their body temperature cooled. This coexisted alongside miasmic theory, which supposed that many illnesses were caused by indeterminant “bad air” or “night air” that spread from swamps and rot.

During the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia, Benjamin Rush, one of the nation’s founding fathers and a physician at the University of Pennsylvania’s Medical School, became a emphatic supporter of the logical end of humoral medicine, known as “heroic” medicine—which took bleeding, blistering, vomiting, and purging to extreme ends in an attempt to balance the humors. Rush was a great proponent of calomel, a mercury chloride compound used to balance yellow bile that was ingested as a white powder or tablet and would cause the patient to vomit, defecate, and drool excessively.

It was a violent approach to health, but it produced immediate effects—removing a pint of blood from a feverish patient will often lower body temperature temporarily, even if it doesn’t solve the illness. Deaths were ascribed to God’s will rather than any failing in treatment methods.

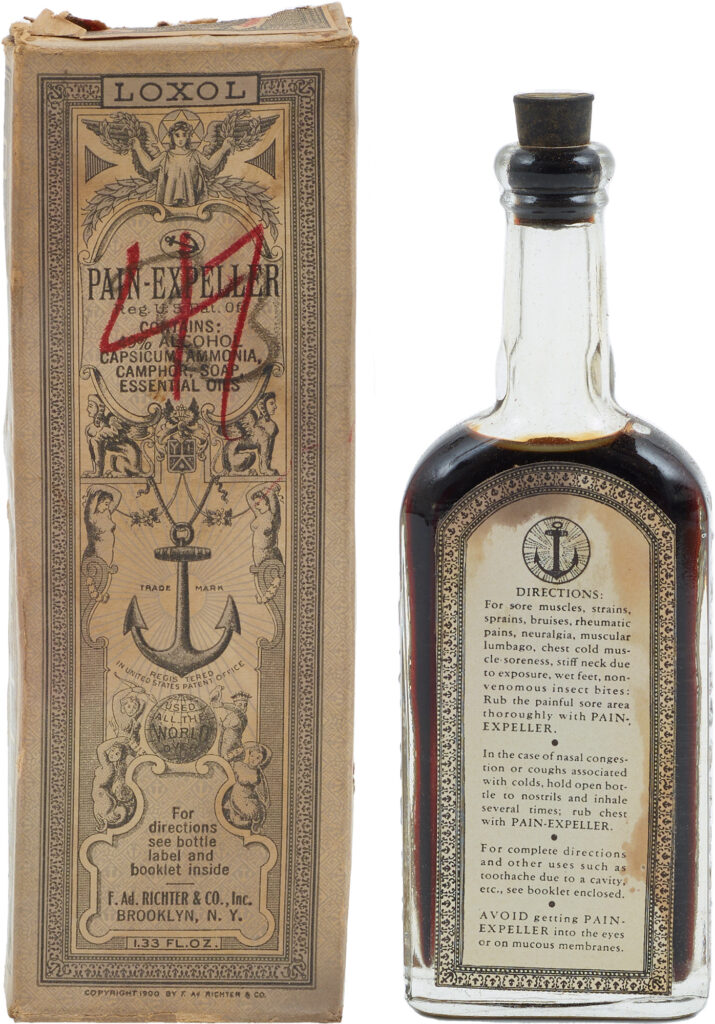

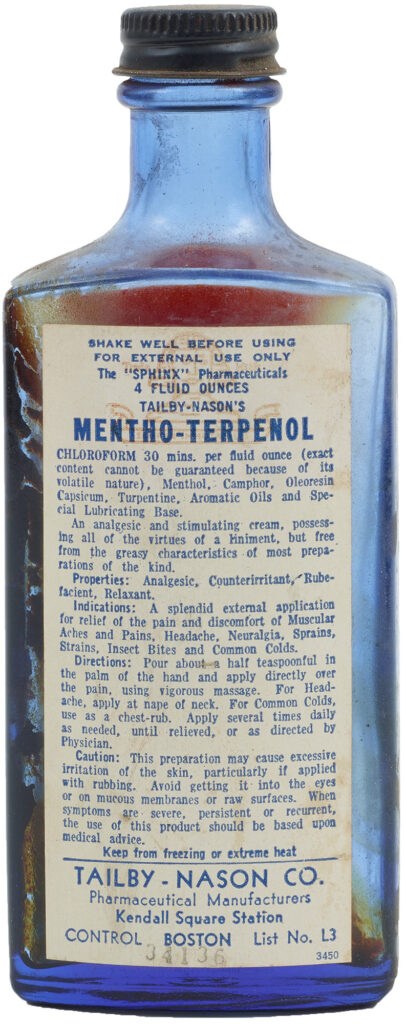

Given the circumstances, it’s easy to see why people would seek out other forms of medicine, and herbs and essential oils were reliable, time-tested alternatives. But they coexisted alongside and in concert with all manner of quack remedies—often patent medicines that made wild promises of miracle cures. Essential oils were often used as a flavoring in these nostrums, which served to exaggerate their supposed healing properties.

Menthol, for example, occurs naturally within peppermint and is responsible for its refreshing sensation. In the same way that the capsaicin in chili peppers creates the sensation of heat, menthol activates a receptor protein that tricks the brain into feeling a chill through a reaction called chemesthesis. It’s also able to activate the brain’s opioid receptors, which is why it’s often used in a salve to soothe sore muscles, sore throats, and alleviate indigestion.

Such utility provided by patent medicines was often offset by the other ingredients. P.P.P. Parson’s Purgative Pills, for example, listed “aloes, colmel, powdered colocynth, gamboge, soap, mandrake root, and peppermint oil” as active ingredients, but researchers in 2013 found the pills also contained mercury. Boom times ended for the patent medicine industry in 1906, after the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act, which required manufacturers to disclose the “miracle ingredients” in the concoctions.

But even after a century of reforms and stunning advances, health care remains an often brutal, prohibitively expensive system that fails many of those who need it most. A study from the Brookings Institution found that the average amount Americans spend on health care quadrupled from 1980 to 2018. Add to this burden skyrocketing grocery, housing, and childcare costs, a crushing opioid epidemic, and a general disconnect between the public and medical professionals—according to PBS nearly a third of Americans do not have a primary care physician—and once again it’s easy to see why people would look elsewhere for treatment.

The wellness industry has eagerly filled this gap. Pressure to optimize every aspect of life—time management, exercise routines, eating habits—has increased even as the quality of life one can expect from this kind of regimen has noticeably declined.

In 2008 actor Gwyneth Paltrow launched Goop as a weekly newsletter, and the business has since grown into a $250 million media and e-commerce empire. The company and Paltrow have been mocked extensively for selling absurd and absurdly expensive products. A vaginal jade egg became a particular object of derision, but Goop got the last laugh. Every time someone mocked the company, it drove traffic to the site—inadvertently creating more potential customers. “I can monetize those eyeballs,” Paltrow told a class of Harvard Business School students in 2018.

In 2018 the wellness brand was sued by 10 California district attorneys who alleged Paltrow’s empire was marketing products with deceptive medical claims—that one of her essential oil blends could cure depression and that the much-ridiculed jade egg could prevent uterine prolapse and incontinence. Goop settled out of court and chalked the charges up to a misunderstanding. These days the company has become warier about the way it markets products, but its store is still full of pseudoscientific paraphernalia, such as an infrared sauna blanket lined with amethyst and tourmaline that promises health benefits from the stones’ electromagnetic field; Altitude Oil, which is intended to help travelers remain clearheaded after long flights; and the jade egg, which it still sells for $66.

When criticized for pandering to wealthy white women and preying on their anxieties, Paltrow has consistently used her customers as a human shield—insisting that to insult her was to insult them. In the years since Goop launched, wellness culture has metastasized through a new generation of companies that often demonize traditional medicine and promise miracle cures just as suspect as those hawked by early American peddlers.

To find the essence peddlers of today, I turn to social media—Instagram and TikTok specifically. Almost all the essential oil influencers I come across are women. They are generally young, many of them young mothers. Their houses, when they appear in the background, are orderly but never fancy. The furniture is nondescript—neutral tones and inoffensive accent pillows—and children and husbands appear occasionally as props. They push essential oil as a cure for acne, depression, indigestion, night terrors, colic; they create dupes of Anthropologie candles; they often look tired.

Most of them work for the two largest essential oil purveyors in the United States, Young Living Essential Oils and doTerra. Both companies are based in Utah, and both are multi-level-marketing schemes.

Young Living was founded in 1994 by Gary Young, a Mormon who served 30 days in prison for practicing medicine without a license and went on to build a cult-like following that survived even after his death in 2018 at age 68. Young promoted a deep distrust of traditional doctors within his organization. In a lecture transcript obtained by Business Insider, Young attributes serious illness to a subconscious failing on the part of the patient. They lack a will to live, he said, and doctors only worsen the situation by allowing patients to evade responsibility. “God didn’t inflict us with the disease either,” said Young. “He allowed us to make our choices and that’s why I say we chose the cancer.”

doTerra was founded in 2008 by a clutch of Young Living executives who split off; it grew rapidly and reached roughly the same size as Young Living by 2012. The two companies have been at loggerheads since then over theft of trade secrets and whose oil is “purer.”

In 1994, U.S. Senator Orrin Hatch of Utah pushed through the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act, which effectively eliminated federal oversight of dietary and herbal supplements—including essential oils, which fall under “botanicals.” Hatch’s bill had two noteworthy effects.

First, it set off a boom in the supplements industry. According to the Journal of Nutrition, the U.S. supplements industry was worth $32.5 billion in 2012. Utah accounted for $7.2 billion of that haul, up from $924 million two decades earlier. It was the state’s largest industry at the time, according to a trade group.

“Few realize health supplements earn more money in Utah than the state’s world-renowned ski tourism industry,” business magazine Utah Stories noted in 2015.

Second, because these supplements are classified as food rather than drugs, regulators are able to act only after a product has caused adverse health effects or if sellers are making blatantly false claims. Although many essential oils are marketed as “therapeutic grade,” there is no agreed-on standard for what that means—it’s just another marketing ploy.

A quick search of “essential oils” on the FDA’s website brings up 30 warning letters; both Young Living and doTerra have been the subject of repeated warnings from the FDA for making false claims about their products’ healing capabilities. Young Living at one point claimed its essential oils could be used to fight Ebola, and salespeople for both companies promoted oil mixes they said would protect customers against COVID-19. Both companies have paid thousands in fines, repeatedly agreed to stop promoting false health claims, and promised to better train their sales representatives.

So far, these efforts have fallen short, and the companies’ associates continue to spread dubious medical advice. In September 2023, a video filmed by a doTerra seller went viral. Optometry, she claimed, was a scam, and if people simply took off their glasses and ingested the appropriate concoction of essential oils, they would finally be able to see.

After several hours of scrolling through essential oil reels online, I am bummed out in a way no lavender spritz can fix. Put diplomatically, these women are selling garbage. Among the oil blends Young Living produces are Chivalry, which costs $73 and is meant to evoke courage, justice, mercy, generosity, faith, nobility, and hope; Brain Power, which sells for $98; and for $74 Dragon Time, which is supposed to be soothing to women for reasons that are left unclear. The bottles are all 5 mL.

The prices are so inflated, and the claims are so out there that the scam seems obvious. This is not to say all the sales reps are actively trying to deceive buyers, though. Mostly, they’re trying to make some cash in a way that feels accessible, sometimes even entertaining, and works around their kids’ schedules. The enduring stereotype of the MLM shill is a Mary Kay sales rep—a bored housewife selling cosmetics on the side. But if there was ever anything to that cliché, it’s long gone. Today, when almost every household requires two incomes to remain solvent, when childcare is not only prohibitively expensive but ends at 3:30 p.m., parents don’t have great options to choose from. Essential oils promise an income with flexible hours, but more crucially they’re an outlet to the outside world, while offering what the companies claim is a social good.

According to Business Insider, 89% of Young Living sales representatives earned an average of only $4 annually in 2020—that’s not a typo. (The average dropped to $3 in 2022.) The company requires new sellers to invest so much money into oils upfront that many never make back their sunk costs.

As I move further through essential oil TikTok, the videos get sadder. No longer are the sales reps young mothers; it’s not entirely clear if they’re even sales reps anymore or just customers. I stumble onto the profile of one woman who appears to be in her 50s or 60s. She has a few videos about doTerra oils getting her through depression, but mostly her videos are about the pain involved in ending her 30-plus-year marriage. She has a young daughter. She posts a lot of Canva graphics about healing, the kind of content that would cause you to forcibly separate a friend from the internet if you saw them interacting with it.

This lady does not need a $70 oil blend, I think as I navigate away from her profile, she needs a spell. Not a revenge spell, just something to get her back on her feet and away from the morose pop songs running over her videos.

I think back to Samara, a young woman who works at Rocky’s Crystals, an occult store not far from Harry’s that specializes in minerals. She told me that in preparation for a big move, she bought a spell candle at Harry’s, one dressed with protection oil.

“It was frankincense and Palo Santo oil, both very good for protection,” she said. “I had just moved out of my family home. Bipolar mother, a lot of chaos in the house. . . . I needed a fresh start, and I needed to jump-start this fresh start without having anything drastic happen. And it worked. It protected me, it made me comfortable enough to talk to other people, so I wasn’t afraid. Spells work!”

When I started reporting this story I found an article by an Inquirer reporter, who, after a particularly bad run of political turmoil and sports losses, became convinced the city itself was cursed and bought bottles of Harry’s protection oil Run Devil Run in an attempt to save Philadelphia. Did it work? I’m not sure, but I buy a bottle anyway just in case someone tries to hex me when this runs.