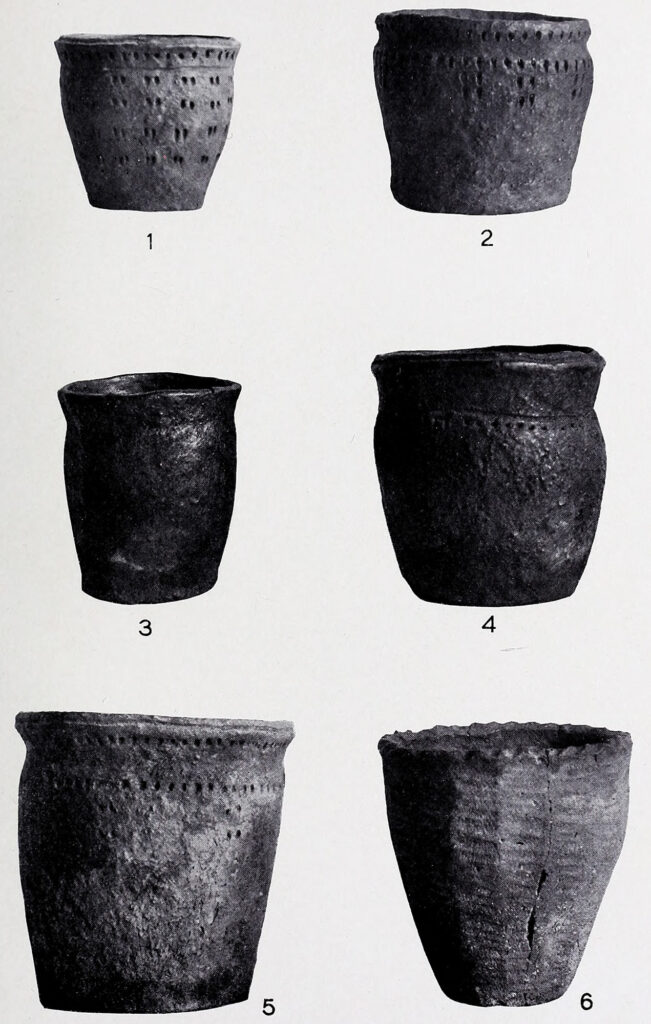

When Karen Harry first saw the artifacts, she snorted and shook her head. She simply did not believe that they were ancient cooking pots—everything about them looked wrong.

Harry, a ceramics archaeologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, works mostly in the desert Southwest of the United States, where Native Americans traditionally made some of the most elegant pottery in the world. But one day in 2003, a colleague at UNLV, Liam Frink, returned from a trip to western Alaska, where he had been excavating sites associated with the Thule people, the ancestors of the modern-day Inuit. Frink showed her the remains of some supposed cooking pots he had collected there. The pieces looked more like chunks of scorched dirt than typical potsherds—blackened and crumbling, like nothing Harry had ever seen.

Cooking pots around the world generally share certain traits. They’re thin-walled, to more easily conduct heat from the fire. They’re large, holding a few gallons of porridge or stew, since they often need to feed a whole family. They’re fired, to seal the walls and prevent water from seeping out. And they’re round-bottomed, for strength.

But the fragments that Frink insisted were old cooking pots lacked all these features. They were small, unfired, thick-walled, and had a cylindrical shape that would have rendered them structurally unsound. (Like most materials, ceramics expand when heated and contract when cooled, and sharp joints—like those on the base of cylindrical flowerpots—often fail and crack when put under such stress.)

Furthermore, according to archaeological theories, the Arctic lifestyle wasn’t compatible with cooking pots. The climate was too cold and damp to make pottery, and the diets up north lacked the grains and starches that would require long, slow simmering. Harry took one look at the remains and dismissed them. They simply could not be cooking pots.

But as Thomas Huxley once said, scientific progress often starts with “the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact.” Despite Harry’s well-reasoned objections, Frink explained that all available archaeological evidence indicated that people in Alaska have been using these small, squat pots for cooking for at least a thousand years. Harry had to figure out what the heck was going on.

Harry and Frink decided to tackle the mystery together and spent the next few years exploring several avenues: in addition to analyzing the archaeological remains Frink collected, they visited Alaska to interview elders, scoured old ethnographic accounts, and, most importantly of all, conducted several experiments that involved recreating Native pots.

The interviews with elders captured some poignant history. Traditional clay pottery fell out of favor in Alaska after contact with Russian traders and other groups introduced metal cookware.

Nevertheless, although the memories were fading, Frink and Harry interviewed two brothers in their late 60s who recalled their mother teaching them how to craft such pots. “According to one of the brothers,” Frink and Harry wrote, “she made the cooking pot not because she intended to use it (according to the elders, they never saw her cook in anything other than a metal utensil), but because she wanted them to have the knowledge just in case it was ever needed.”

Even if the practical utility of the pots had seemingly diminished then, they continued to preserve these cultural traditions.

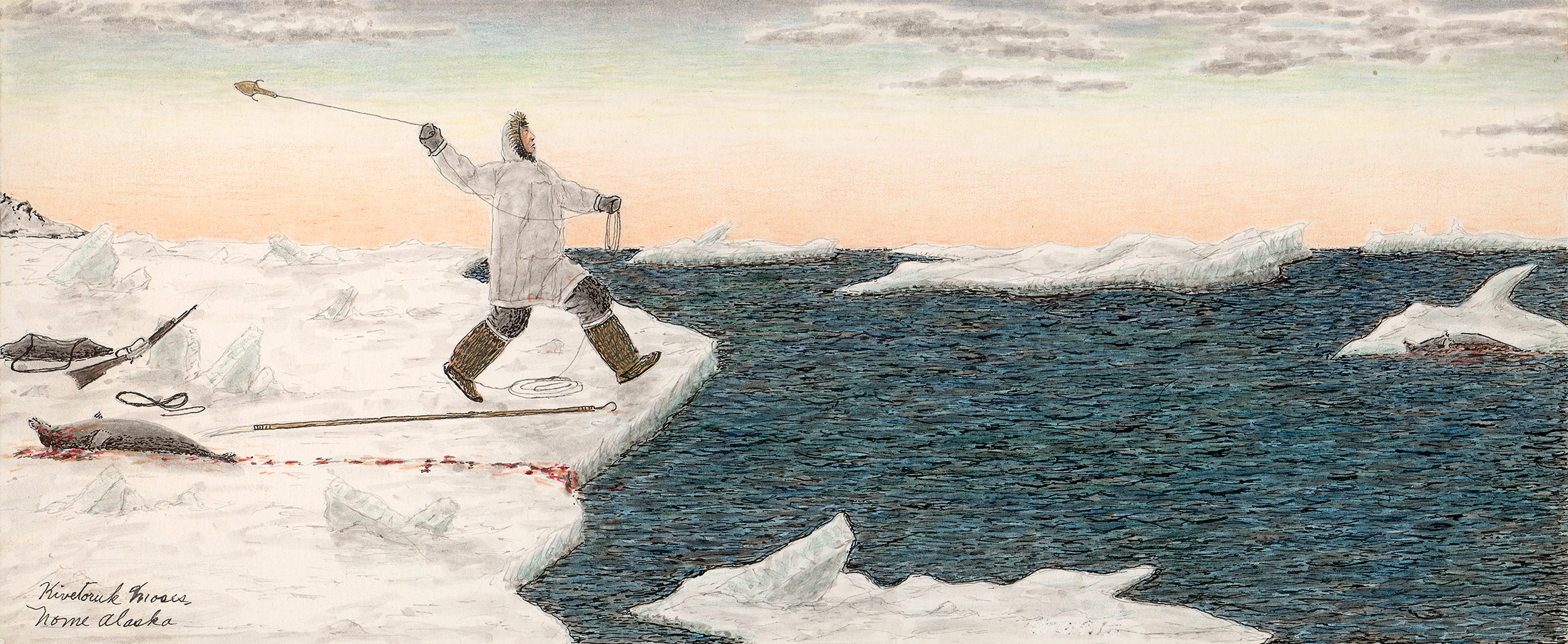

Thankfully, one mystery gave way easily—the pots’ small size. Traditionally, the Thule and other people derived most of their food from hunting seals, walruses, and whales, and they ate most of the flesh raw, as a palliative against scurvy, a chronic lack of vitamin C. Most traditional societies ingested vitamin C through plants, but given the dearth of edible plants in the far north, especially during winter, that wasn’t an option. Animal flesh contains plenty of vitamin C, but only in raw form, since heat destroys the nutrient. Consuming raw flesh, then, was a necessary adaptation to Arctic life.

Still, there is something nice about a warm meal sometimes. Traditional Alaskan cuisine also prizes texture contrasts, including one dish that involved dunking chunks of frozen meat in boiling water. This produced a soft, warm outer shell with a frozen crunch in the middle. Small pots were perfect for dishes like this, since the Thule simply needed to parboil a few bites at a time, not simmer a big kettle of stew. The small size of Alaskan pots, then, was simply a reflection of culinary habits.

But if the pots’ size now made sense to Harry and Frink, other mysteries persisted. Why the thick, unfired walls and sharp, stress-prone joints?

These characteristics, it turns out, were a byproduct of the damp climate of Northern Alaska. Most traditional societies across the world sealed pots by firing them. On a microscopic level, putting the pots in a kiln or near flames will initiate a process called sintering where the tiny individual grains of clay fuse together into one hard, solid mass. If a pot isn’t sintered or otherwise sealed, the cooking liquid will leach into the pot’s walls, crumbling them and contaminating the food. Before long, the pot collapses.