Kate Pickert. Radical: The Science, Culture, and History of Breast Cancer in America. Little, Brown Spark, 2019. 336 pp. $28.

Ask the average American woman what she knows about breast cancer prevention and treatment, and she’s likely to reply, “Get a mammogram every year beginning at age 40.” That’s certainly the message suggested by the dozens of pink-beribboned items appearing every October during Breast Cancer Awareness Month. And it’s the message in the ads for mobile mammogram vans: “Early detection saves lives. Get your mammogram.”

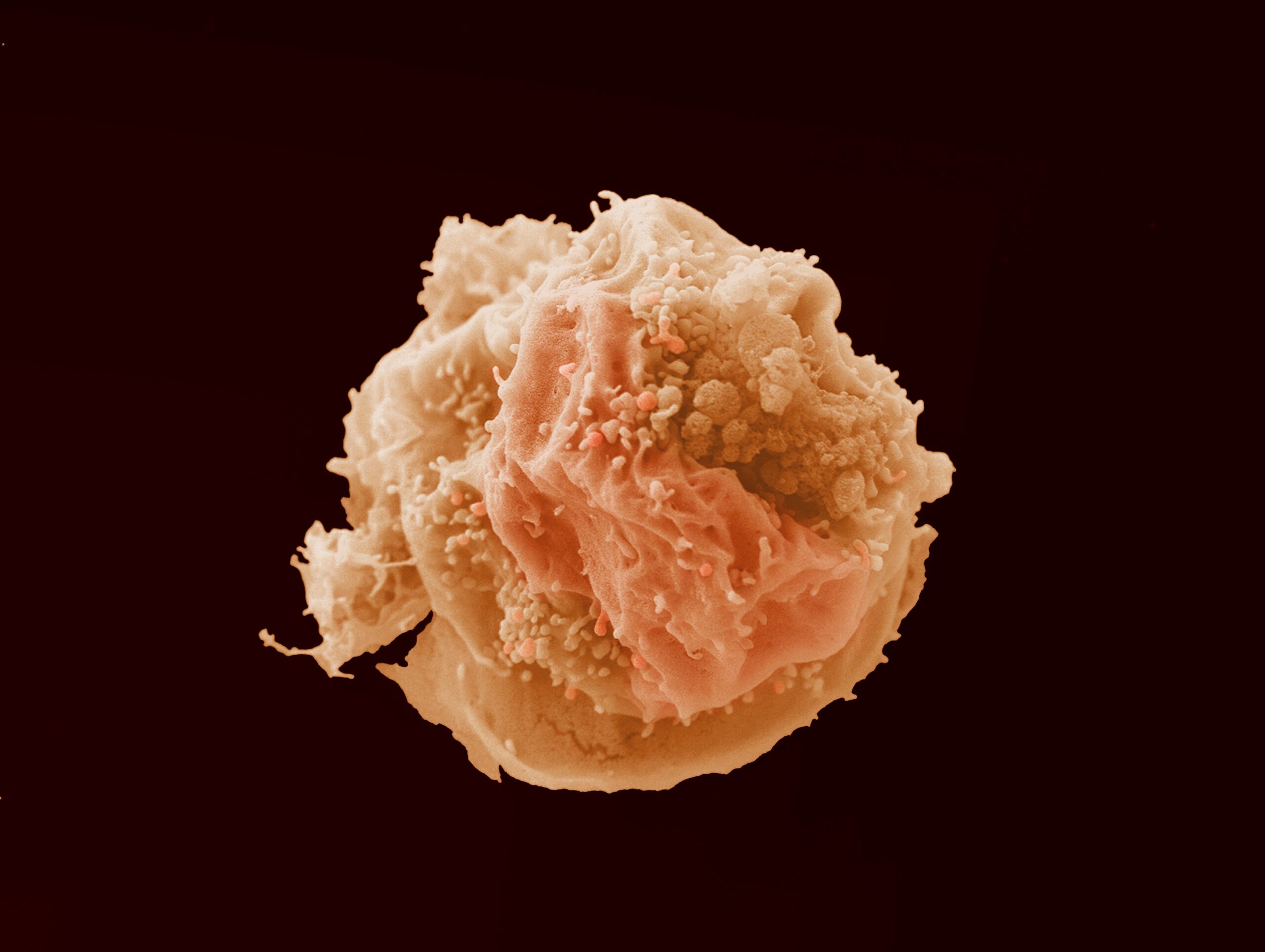

But no mammogram alerted Kate Pickert to the fact she had breast cancer; instead it was an oozing nipple. Imaging revealed calcifications, which may indicate the presence of breast cancer. Her doctor ordered a biopsy. Pickert, a former health reporter for Time who knows something about unnecessary testing, asked if a biopsy was needed. The radiologist insisted, and good thing, too: the test revealed ductal carcinoma in situ (or DCIS), abnormal cells inside a milk duct in the breast. It’s sometimes called stage 0 breast cancer. Further testing uncovered two invasive tumors and that cancer had spread to lymph nodes.

Pickert endured chemotherapy, radiation, and a double mastectomy, treatment that so far has kept her cancer at bay. “I had gone from being a happy mom and wife to a dying woman and back again in less than a year,” she writes in Radical: The Science, Culture, and History of Breast Cancer in America, a book that “began as an attempt to understand that boomerang.”

The estimated cost of mammography screening in the United States in 2010 was $7.8 billion, with approximately 70% of women age 40 to 85 participating, according to a 2014 study published in Annals of Internal Medicine. But many researchers now believe these annual screenings might be a waste and might lead to more harm than good.

Even suggesting regular mammograms aren’t essential to ensuring women’s health can make people feel nervous. What? Not get a mammogram? But early detection saves lives! This “fact,” says Pickert, has been drilled into us since the 1980s by “public campaigns that were intentionally simplistic and easy to understand.” Researchers, however, had little evidence for the usefulness of mammograms in women younger than 50. But given the number of 40-something women developing breast cancer, it seemed worth trying. And so, Pickert concludes, “Getting annual mammograms at the age of forty became a rite of passage for American women.”

In 2009 the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), which evaluates the effectiveness of tests and treatments independent of their financial cost, reviewed decades of data on hundreds of thousands of women to determine the best use of mammography. The task force concluded that women in their 40s—unless they have particular risk factors—don’t really need mammograms at all because the number of false-positive results far outweighs the number of tumors found. The USPSTF also determined that women age 50 to 74 should be screened every two years instead of every year.

The country erupted when the findings were released. Health advocacy groups feared insurance companies might use the report as an excuse to quit paying for mammograms. (USPSTF recommendations aren’t binding, but they are frequently used by insurance companies to determine coverage.) The American Cancer Society, the American College of Radiology, and other special-interest groups produced a flurry of press releases in support of the status quo. “A few weeks later, the U.S. Senate passed a law barring Medicare and Medicaid from refusing to cover screening mammograms for forty-something women,” Pickert writes. “Politicians of all stripes seemed to agree on one thing—the task force was wrong.”

Diana Petitti, then the vice chair of the USPSTF, received death threats. “I am the ultimate rationalist,” Petitti tells Pickert. “This is the rational way to interpret this data.” She was completely unprepared for the onslaught: “You should die,” the email messages read. “I hope you die.”

Such vitriol seems particularly senseless given that mammography might not even be the best tool to detect breast cancer. The majority of cases are found through human touch: by gynecologists during a woman’s annual visit (13%) or, as was the case with Pickert, by the women themselves (43%). Mammograms reveal another 43%, but it turns out the superior technology may be magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is better than X-rays at picking up high-grade DCIS, the type of DCIS most likely to become aggressive and invasive. MRIs also show tiny and fast-growing tumors earlier than the low-dose X-rays used in mammography, and MRIs produce no harmful radiation.

MRIs are especially preferable for women with dense breast tissue. Mammograms have a hard time penetrating such tissue, allowing tumors to lurk undetected. Nearly half of all adult women and an even larger share of younger women have dense breast tissue. “Having dense breast tissue can hide a tumor on a mammogram and also increases the odds a woman will develop breast cancer,” explains Pickert. “And yet, for decades, women with dense breasts . . . were not told that the value of their annual screening mammograms was diminished by this fact.” That is, our default tool for detecting breast cancer falls short for about half the population using it.

Pickert interviewed Christine Kuhl, a German radiologist and the chair of the radiology department at RWTH Aachen University, who is studying whether MRIs might be used as a widespread screening tool. She is looking particularly at abbreviated MRIs, which take only five minutes to complete and produce only a few images. Standard MRI breast screening takes between 45 minutes and an hour, but Kuhl has found abbreviated MRI works just as well at picking up cancer. Since MRI can detect cancer so much earlier than mammography, a screening window of every two to three years would be sufficient. Yet this idea, Pickert writes, “unnerves many doctors, who say it’s far too early to know whether the upside of the test (finding more cancer) justifies the downside (finding too much cancer).” Kuhl pushes back hard against such trepidation: “People who say we can’t use MRI due to a lack of evidence are the ones who simply don’t want a change. Of course, overdiagnosis is a problem. But the main problem we have right now is underdiagnosis.”

Kuhl is a David facing a Goliath. “The oncology community’s obsession with mammography has saved lives,” writes Pickert, “but as I talked to Kuhl it became clear to me that faith in the technology has also stunted scientific inquiry. Other tests exist or could be developed to improve breast cancer screening, but mammography has remained the dominant technology, even in the face of evidence that it falls short for many women. For all the awareness about breast cancer, women, by and large, remain unaware of their risk of developing the disease and oblivious to the fact that the primary tool used to screen for it often does not work.”

Why is the medical establishment so slow to pivot away from yearly mammograms starting at age 40 toward more productive methods, whether that’s a reduced screening schedule or a switch to MRIs? One reason is the fear of more false-positive results with MRIs and the subsequent costs, but inertia is also to blame. The system we have is mostly (sort of) working (for some people), so why expend a lot of effort to change it? Increasing complexity—whether that’s personalized medicine, different screening options for different types of breasts, or some other consideration—means more work.

Another roadblock to change—at least to cutting back on mammography, whether by starting at age 50 or shifting to biennial screening—is pushback from radiologists. Radiologists make their living reading mammograms. Cuts in screening mean cuts in income. Doctors’ careers can sometimes trump patients’ needs. Pickert argues that some doctors are “more dedicated to their disciplines and careers than to their patients, staking out turf and defending their domains rather than responding to new science and working together.”

Finally, there’s the fear women might abandon regular breast screenings altogether. Deborah Rhodes, who studies breast imaging techniques at the Mayo Clinic, was initially surprised by the difficulties posed by dense breast tissue and remains surprised no one ever seems to share that fact with patients. She tells Pickert, “The mammography community and advocacy groups have been very reluctant to communicate it in plain English precisely because they worry that it will erode confidence in mammography and women won’t do it at all.” (Rhodes is researching yet another screening technology, molecular breast imaging, or MBI, in which the patient is injected with a radioactive tracer that’s absorbed by cancer cells, making them much easier to spot.)

The fact that breast cancer is so strongly associated with women (even though men can be diagnosed with it) may also be a stumbling block. The medical establishment has a long, well-documented history of taking women’s health care complaints less seriously than those of men. A 2019 article in the Washington Post concluded that “women’s pain is . . . less thoroughly investigated, especially initially, when the cause of pain is unknown.” The same article reported that a 2008 study of patients visiting an emergency department found “women waited an average of 16 minutes longer than men to get medication when reporting abdominal pain and were less likely to receive it.” Amy Miller, president and CEO of the Society for Women’s Health Research, says it’s common for women—particularly those with pelvic and menstrual pain caused by such conditions as endometriosis and fibroids—to be told their pain is just a normal part of being a woman.

This problem is compounded by our society’s socialization of women: they’re taught not to make waves. Don’t be assertive, listen to the experienced doctor, be a good girl. If we complain about our pain, we’re seen as melodramatic—look up the etymology of the word hysterical—leaving many women hesitant to even broach the subject, which in turn may lead to poorer care. It’s a catch-22: complain about pain, and you’ll be dismissed as exaggerating; don’t mention your pain, and it won’t be treated. As I wrote this piece, a friend of mine died from metastatic breast cancer at age 36. Like so many women diagnosed with breast cancer, she found it herself rather than through a mammogram, and her one regret was “not pushing my OB/GYN on what I knew wasn’t a clogged duct.”

My friend asked that instead of describing her as having lost her battle with cancer, we say that she was assassinated by cancer. So here’s to you, Linda Shaver-Gleason, assassinated by cancer, and in Linda’s memory I encourage everyone with breasts to examine them regularly and push for medical attention when you believe it is warranted.