One hundred and fifty years ago a Kentucky doctor and Confederate agent worked tirelessly through the summer heat on the island of Bermuda. By day he treated men and women stricken by yellow fever; by night he collected and hid away the soiled clothes and bedding of the dead.

Even as this well-known humanitarian worked to save lives, he was concocting a scheme he hoped would decimate the Union army’s ranks and change the course of the American Civil War.

Luke Pryor Blackburn was born into a politically well-connected family, but after spending an undistinguished term in the Kentucky General Assembly in 1843, he left politics for a career in medicine. In the years that followed, Blackburn established himself as an expert in treating yellow fever and gained prominence for his humanitarian impulses. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Blackburn sided with the Confederacy. But at age 44 the doctor was too old to enlist in the army. Instead, his political connections and professional expertise were put to use as an envoy and a doctor to the Confederacy. His duties eventually led him to Canada, where he helped organize Southern blockade runners bringing supplies to the rebel army.

In Toronto, Blackburn met Colonel Jacob Thompson, a Confederate spy and former member of President James Buchanan’s cabinet, and Godfrey Joseph Hyams, an impoverished English shoemaker displaced by Northern troops from his Arkansas home. In 1864 the South was in retreat, and the Confederates were desperate for a way to turn the tide. Blackburn, who knew firsthand how yellow fever could ravage a population, hatched a plan: infect Northern cities and Northern-occupied cities in the South by unleashing the fever on Union troops using the vomit- and blood-soaked clothes of ill and dying yellow-fever sufferers. He had only to wait for a new outbreak to acquire the infected clothing. Thompson agreed to help fund the scheme, and Blackburn promised Hyams $100,000 for distributing the clothes.

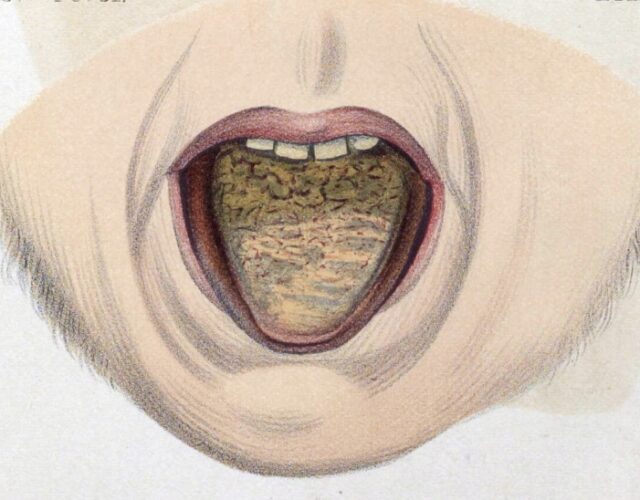

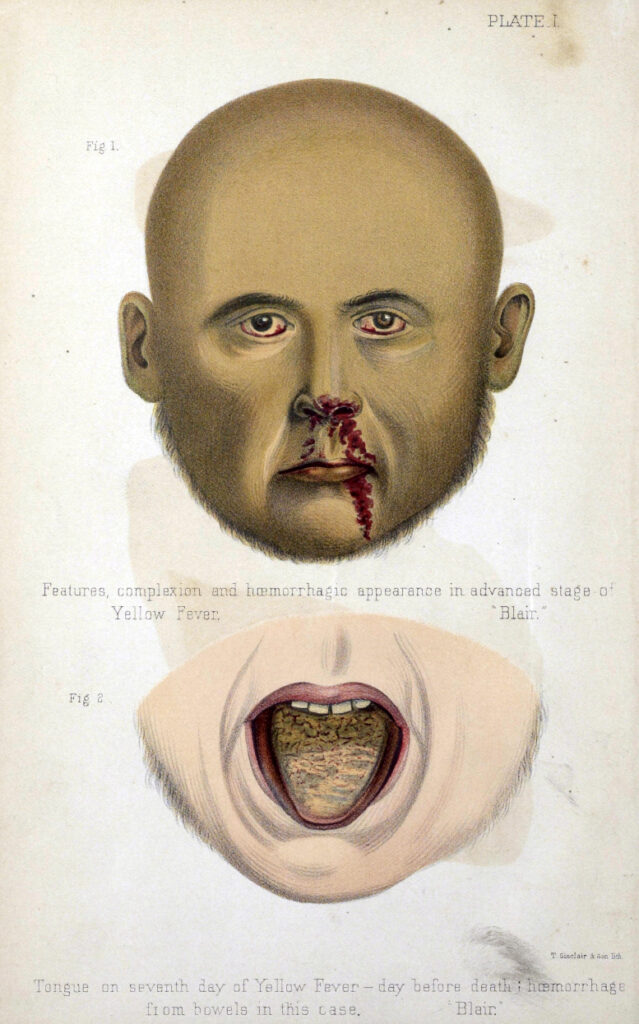

Yellow fever is a viral infection transmitted mainly by the Aedes aegypti mosquito and, when severe, can put its sufferers through days of hemorrhaging, vomiting, and pain before killing them. It gets its name from the sickly yellowish hue a victim’s eyes and skin take on. During epidemics yellow fever can kill up to half of those who develop its severe form. Even today the disease is life threatening to the unvaccinated. At a time when viruses had yet to be discovered and mosquitoes were considered a nuisance rather than a vector of disease, Blackburn erroneously expected the sweat, blood, and vomit on dead men’s clothes to transmit yellow fever and, most important, disrupt the Union army.

In April 1864 Blackburn learned of an outbreak in Bermuda. He volunteered to sail to the island and treat the sick for free, instructing Hyams to stay in Canada and await his orders. Once in Bermuda, Blackburn spent weeks treating patients ill with yellow fever; all the while he secretly collected victims’ bedsheets and clothing and stored them in trunks. When the epidemic ended in July 1864, Blackburn returned to Canada with more luggage than he had left with.(He later returned to Bermuda to stock up on even more “infected” clothing.) Blackburn passed the trunks to Hyams, instructing him to auction them off in cities occupied by Union troops. He warned Hyams that the clothing was contagious, cautioning him to handle the contents of the trunks with care and to always wear gloves. Hyams’s final stop, in August, was Washington, D.C., where he sold the trunk Blackburn had called “Big No. 2,” containing goods Blackburn had said “will kill them at sixty yards’ distance.”

Eager for his payment, Hyams returned to Canada and met Blackburn. The Kentucky doctor would only give Hyams $50 for his work, claiming that he wanted confirmation the clothes had been sold before giving Hyams the rest of the promised $100,000. After trying repeatedly to get his money, Hyams realized Blackburn would not pay up.

Frustrated and desperate for cash, Hyams revealed the conspiracy to the U.S. consulate in Toronto on April 12, 1865, three days after Southern General Robert E. Lee’s surrender and the day before Lincoln’s assassination. In exchange for testifying against Blackburn, Hyams was granted full immunity and paid (a fact Blackburn would later use in his defense). Blackburn was arrested by Canadian police in May 1865 for plotting an act of war against the United States while living in Canada (violating the nations’ neutrality agreement) but was acquitted when the court found only circumstantial evidence. (Most of the trunks of clothes were lost, and not all of Hyams’s testimony could be confirmed.)

But Blackburn wasn’t out of trouble yet. U.S. authorities still had a warrant out on the doctor for conspiracy to commit murder with his yellow-fever plot. The United States also suspected Blackburn was a coconspirator of John Wilkes Booth in his plot to assassinate the president. According to Hyams, Blackburn packed a trunk of bloodstained fancy shirts especially for Lincoln. Hyams for his part said he refused to deliver the package.

Blackburn denied ever hatching a scheme to spread yellow fever. But Hyams’s testimony was reinforced by testimony from people in Bermuda at the time of Blackburn’s visit, and there were records of Hyams’s auctions. Details may be lost to time, but clearly Blackburn was up to something.

Northern newsmen were convinced of Blackburn’s guilt, and his infamy grew. In 1865 the Montreal Gazette called his plan an “outrage against humanity” and referred to him as “Dr. Black Vomit” and the “Yellow Fever Fiend.”

In the years after the war a homesick Blackburn tried to rebuild his reputation; he offered to help during outbreaks of yellow fever and at one point wrote directly to President Andrew Johnson asking for leniency. He never received a reply.

In 1872, seven years after the war’s end, Blackburn quietly crossed the border, returned to his Kentucky home, and began doctoring again. He was never arrested on the murder charges.

Blackburn’s coconspirator Thompson, who also orchestrated a string of train robberies and attacks on Northern infrastructure during the war, followed a similar path. Thompson fled to Europe for a few years, eventually returning to his home in Mississippi without facing prosecution. After testifying against Blackburn, Hyams wasn’t heard from again.

Eventually Blackburn’s prestige from fighting yellow fever eclipsed his infamy. He ran for governor of Kentucky in 1879, leaving the campaign for a time to battle against another outbreak of yellow fever. Despite a resurgence of bad press, Blackburn won the election. Once in office he worked to improve conditions in Kentucky’s prisons.

In war and peace Blackburn was defined by his work with yellow fever, although he never could have known why his plot failed. He died in 1887, more than a decade before mosquitoes were confirmed as the carriers of yellow fever. The people Blackburn served later in life only knew him as a doctor and a governor. Four years after his death the state of Kentucky erected a monument by Blackburn’s grave. The parable of the Good Samaritan appears in bas relief.