Here, Kitty, Kitty . . .

Searching for the cats hiding in our collections.

Searching for the cats hiding in our collections.

Last year, the collections blog celebrated the dog days of summer with a post about dogs in our collections by then-Curatorial Fellow Sheu. Now, I love dogs. I love all animals. But I’m especially partial to cats, since I’ve been sharing my home and rescuing and fostering them for many years. And so I vowed to respond with an investigation of cats in our collections.

My mission is not purely personal: Philadelphia, where the Science History Institute is located, was recently ranked as the sixth U.S. city for cat ownership. And surely there’s some kinship between cats—renowned for their curiosity—and the scientific investigators that create, as well as the researchers that use, our collections.

So where are our collection cats? As any cat caretaker knows, the animals are experts at finding secluded or unexpected spots in which to lounge. It turns out that the cats in our collections are also a bit challenging to find, but with dedicated searching, I’ve turned up a charming clowder.

The earliest cat I could find in our collections appears in a printer’s device on the title page of a 1595 book about military art and science: Girolamo Ruscell’s Precetti della militia moderna. This handsome mouser is the trademark of the Sessa Printing House.

Other early works in which cats make an appearance are two 17th-century paintings in our fine art collection. In The Alchemist in His Laboratory (1649), a cat passes through the lower-right hand corner of the image, his curious gaze on a large bowl as if he’s considering dipping his paw into the vessel. In The Alchemist (1600s), a cat stares intently at a mouse, as focused on his work as the alchemists are on theirs. Whereas Sheu found that dogs frequently appear in scenes of alchemical laboratories as steadfast companions, curled up quietly in bed while their “masters” work, only these two alchemical paintings in our collection depict cats. Given their propensity for knocking things over, perhaps it’s no surprise that cats are not depicted as welcome participants in alchemical work.

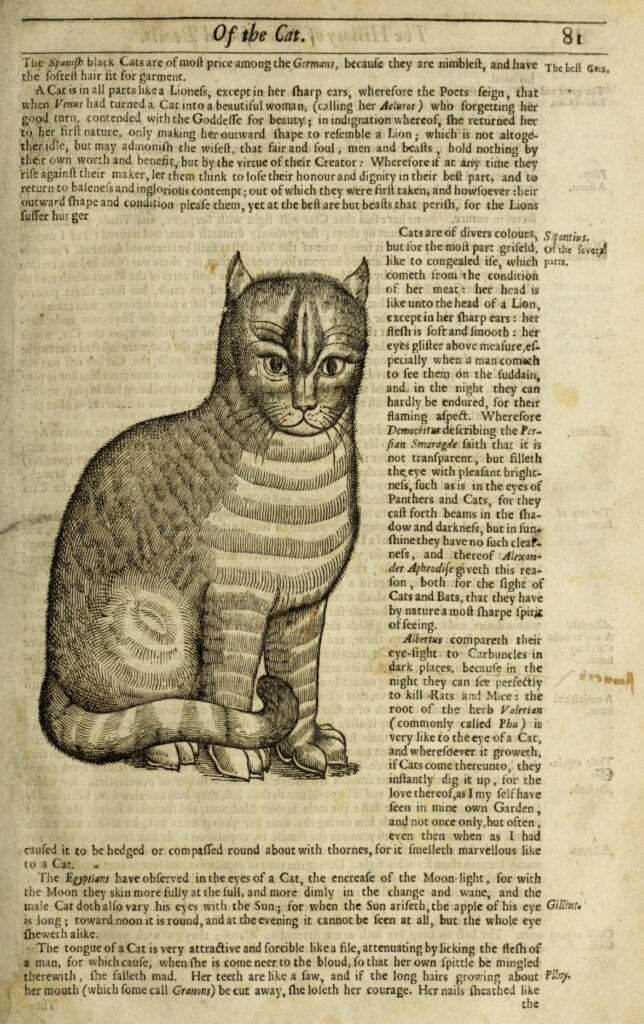

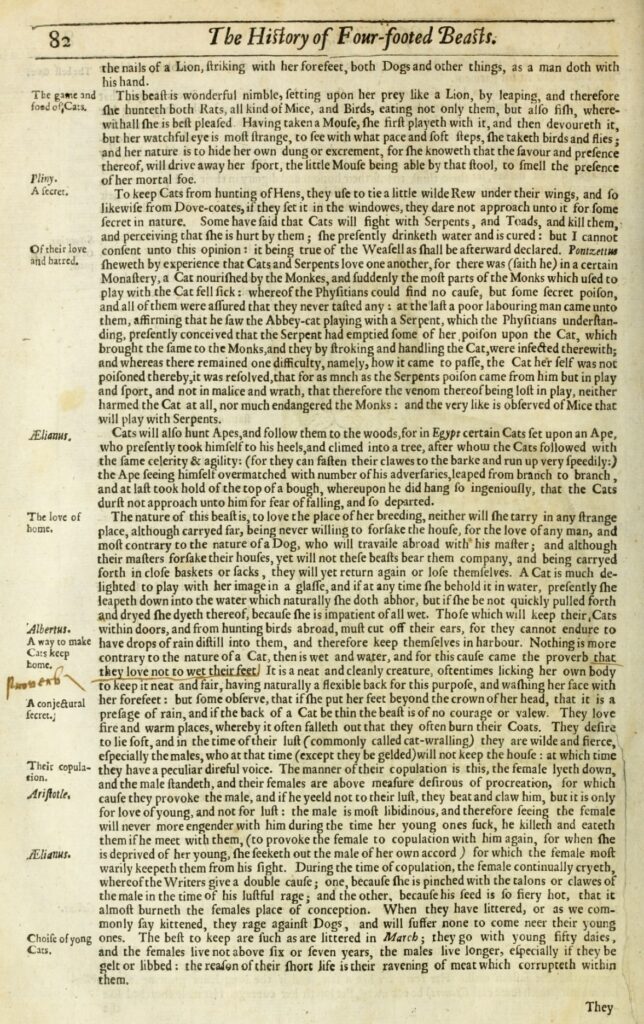

The earliest textual mention that I found of cats in our library collection is Edward Topsell’s The History of Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents (1658), which devotes five pages to the domestic cat. Things start out well, with a discussion of how the ancient Egyptians worshiped cats, only to take a turn: “And not only the Egyptians were fools in this kind, but the Arabians also, who worshipped a cat for a god.”

What’s the problem, Edward?

Otherwise, the description sounds familiar to the contemporary cat lover: Cats do not like to travel. They like to play with their image in a mirror. They dislike water. They are “neat and cleanly creature[s].”

Illustration and description of the domestic cat, from The History of Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents, 1658.

A cluster of 19th-century natural science books present the domestic cat with varying degrees of enthusiasm and accuracy, but always a fun picture!

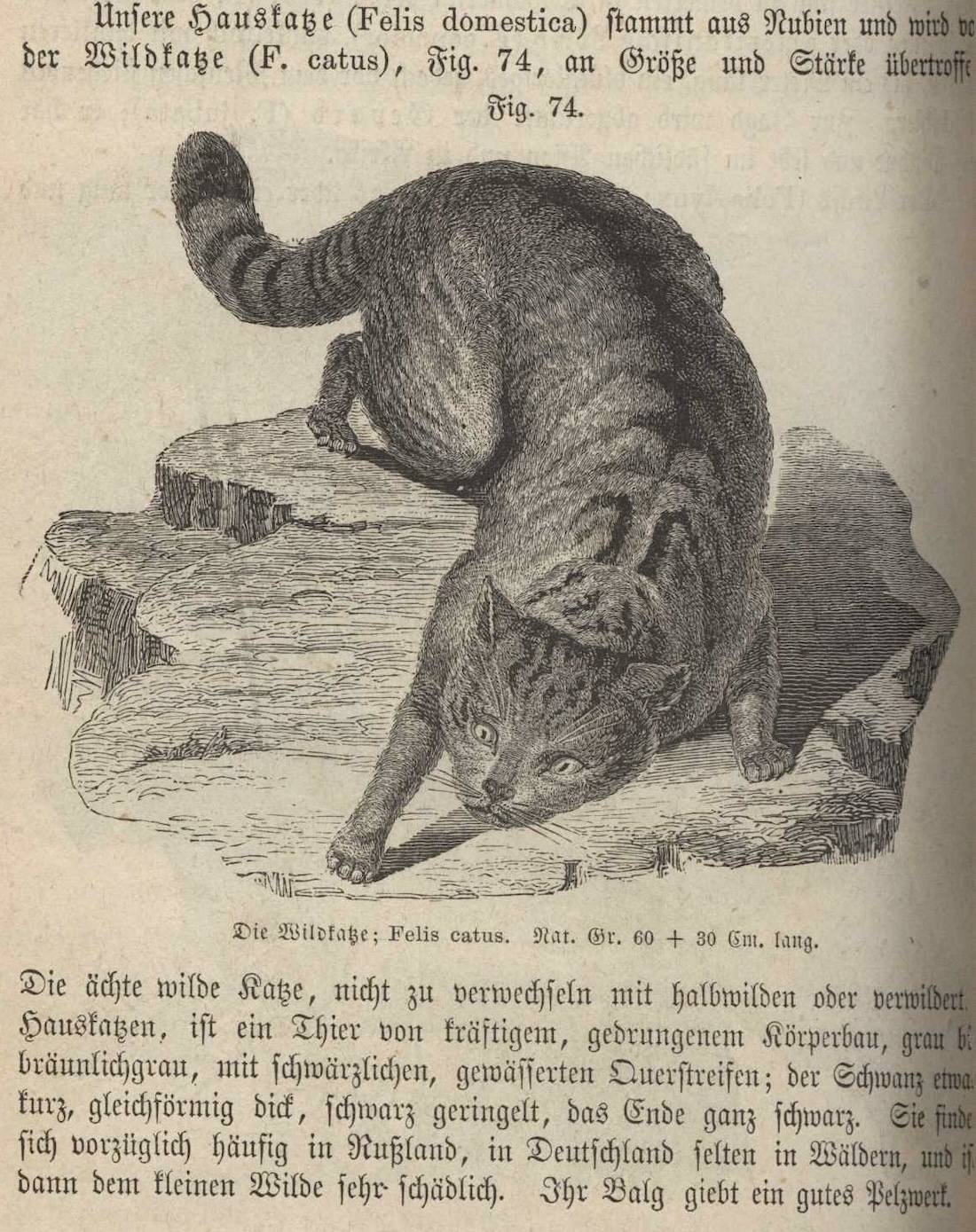

In Friedrich Schoedler’s Das Buch der Natur (1875), the familiar domestic cat gets only a brief mention as a counterpart to the “true wild cat”: “Our domestic cat (Felis domestica) originates from Nubia and is surpassed in size and strength by the wild cat (F. catus) . . . The true wild cat, not to be confused with semi-wild or feral domestic cats, is an animal with a powerful, stocky build, gray to brownish-gray, with blackish, watery transverse stripes. The tail is somewhat short, uniformly thick, black-ringed, and completely black at the end. It is found mainly in Russia, rarely in forests in Germany, and is then very harmful to wildlife.”

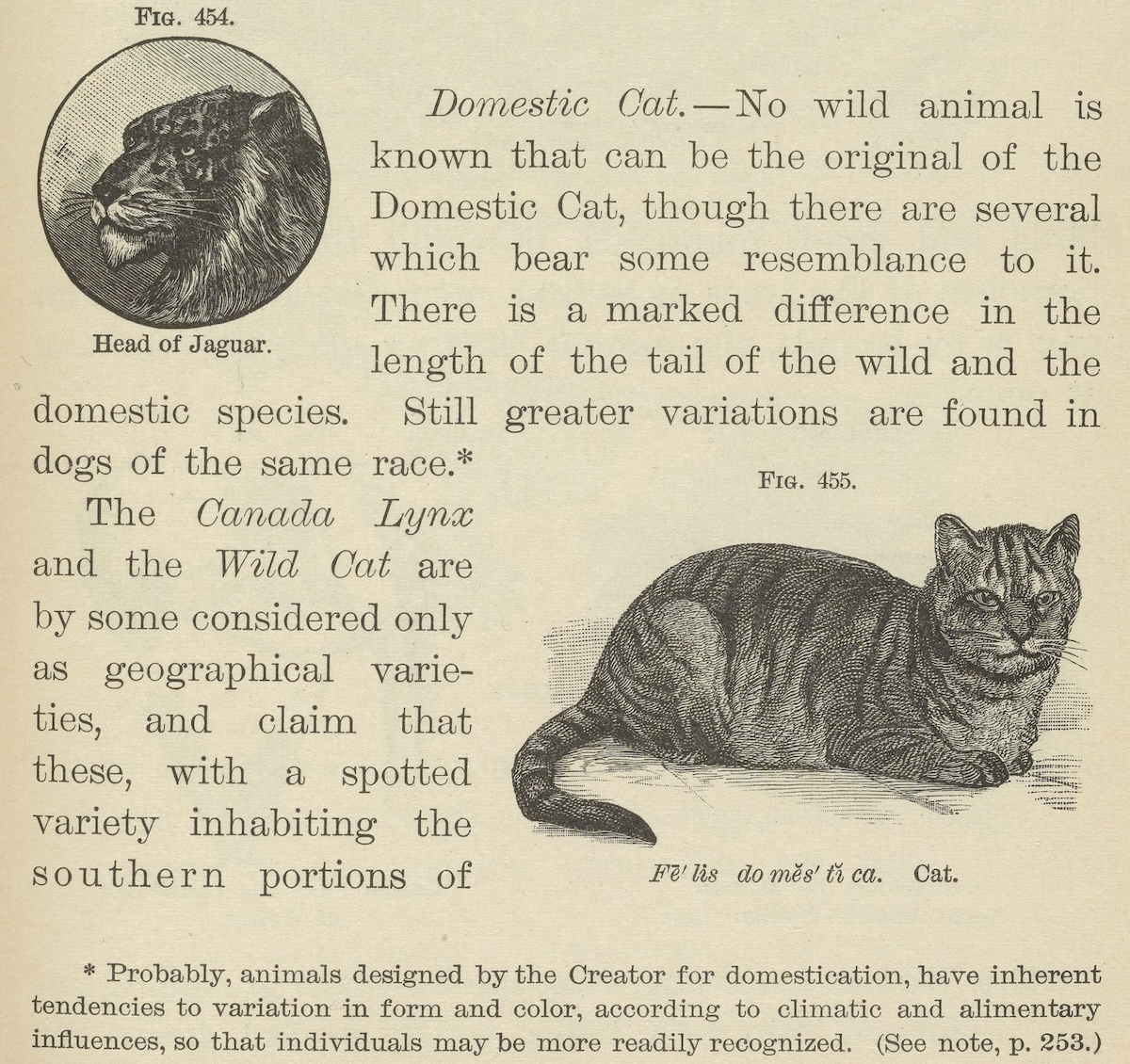

Popular Zoology (1887) concludes a section on tigers, lions, leopards, pumas, and jaguars with this humble fellow, who I would not kick off my couch.

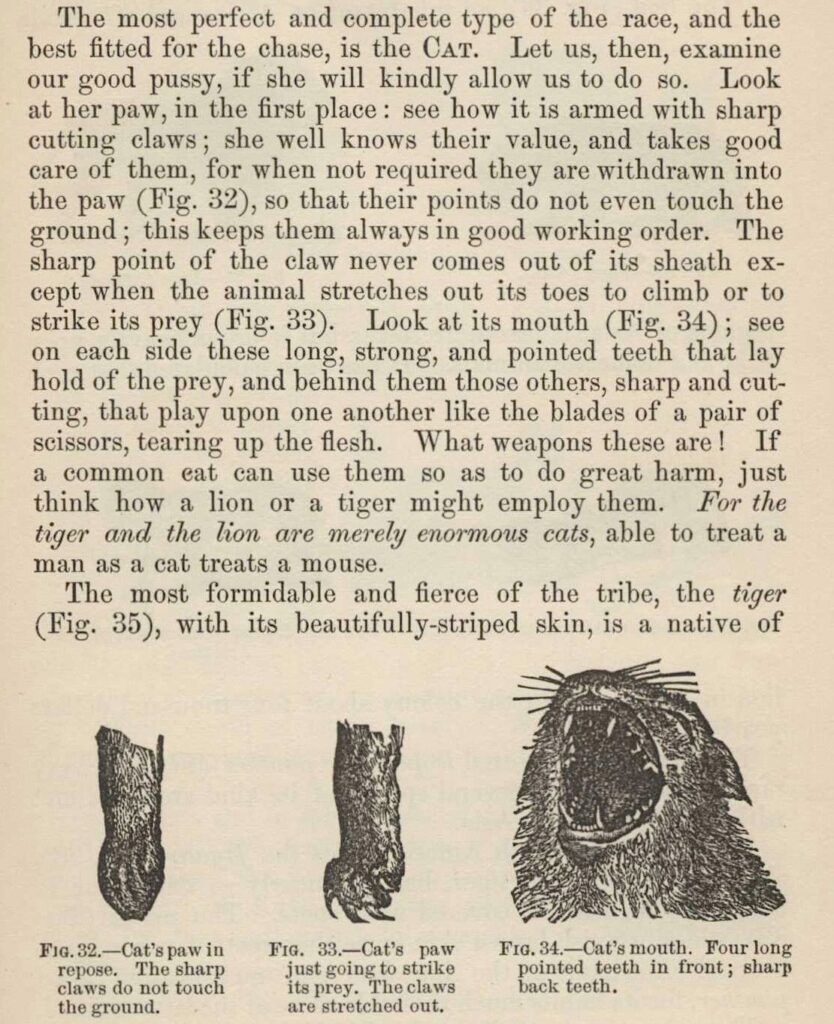

In Paul Bert’s First Steps in Scientific Knowledge (1887), cats, including our domestic companion cats, sound like the monster in a horror film: “We will now begin to study animals that live upon flesh, that devour mammals and birds alive. Those are the Ferine, or carnivorous animals . . . The most perfect and complete type of the race, and the best fitted for the chase, is the CAT.”

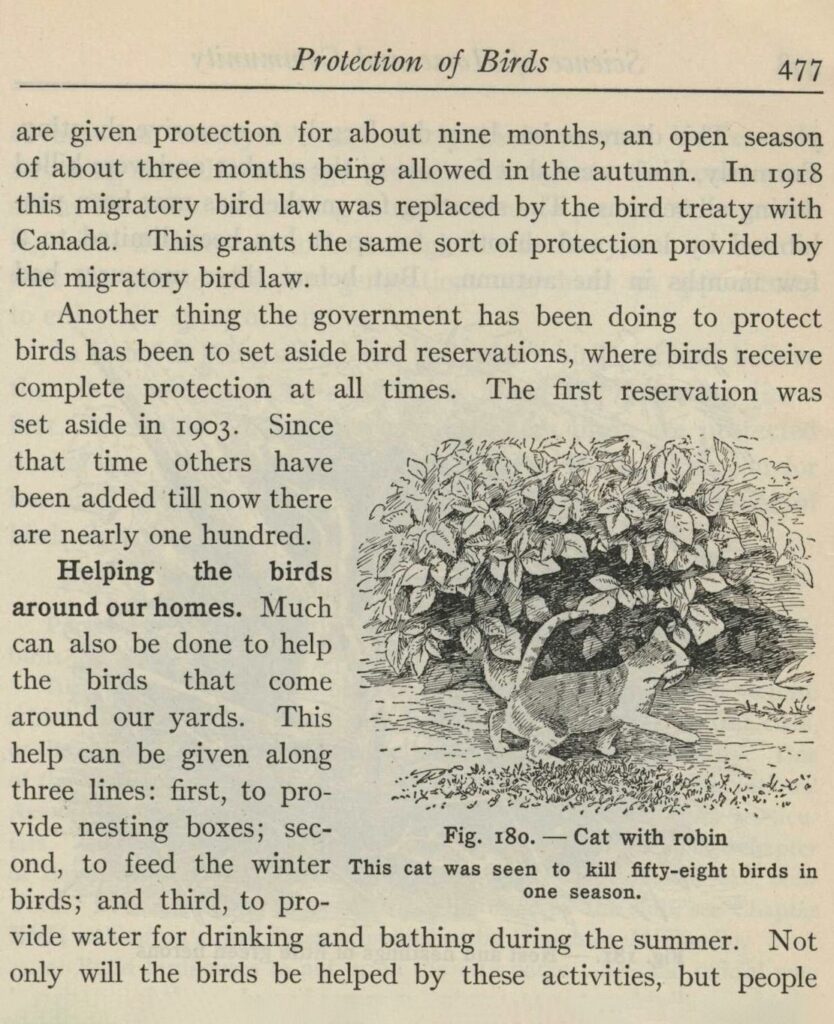

The cats-as-murderers motif pops up again in Science of Home and Community (1926), which discusses cats only insofar as they hunt birds, and ignores their otherwise considerable charms or qualitiies of scientific interest.

Faster pussy cat, kill kill! Left: Figs. 32, 33, and 34. Illustrations of a cat’s paw and mouth, from First Steps in Scientific Knowledge, 1887; Right: Fig. 180. Cat with robin, from Science of Home and Community, 1926.

Speaking of scientific interest, quite a few works aimed at juvenile scientists suggest using a cat as the unwitting subject of an experiment in static electricity. In Electrical Experiments: A Manual of Instructive Amusement (1891), G. E. Bonney writes:

Adding insult to injury, Bonney implies that only a grumpy cat would take umbrage at this activity: “The animal suffers some discomfort on drawing sparks from her in this way, and unamiable cats are liable to resent such liberties.”

I hope that ol’ Murder Mittens scratched anyone who tried this!

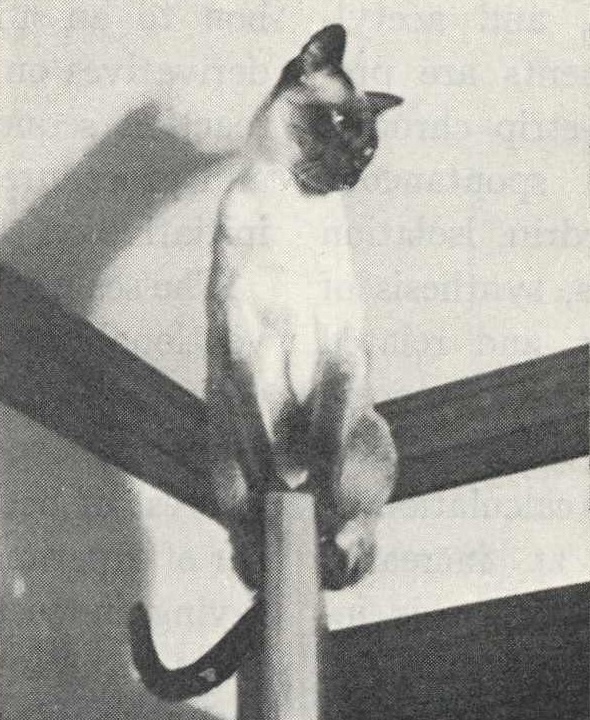

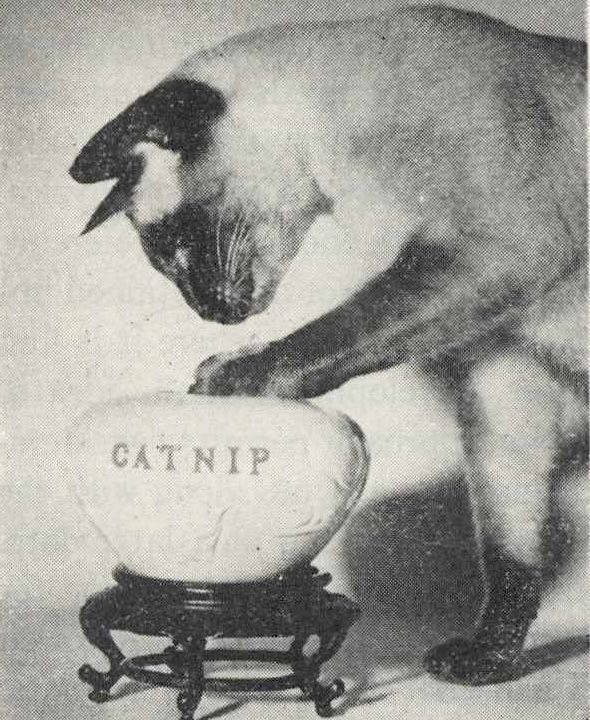

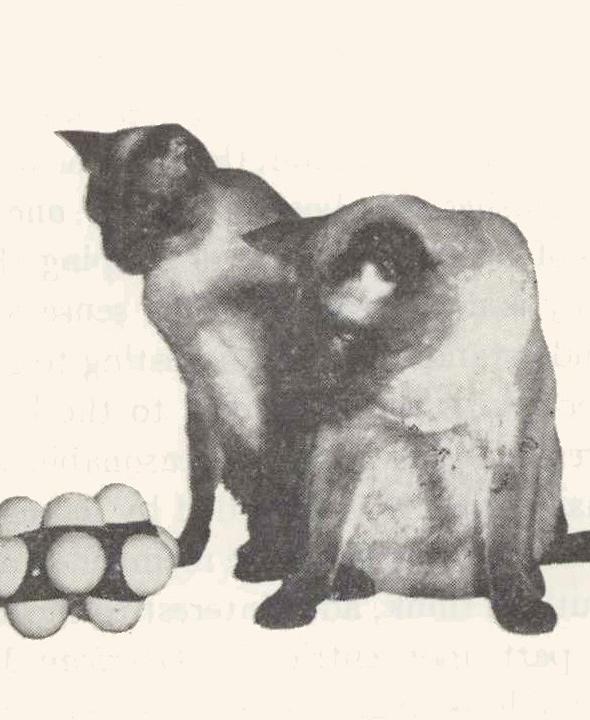

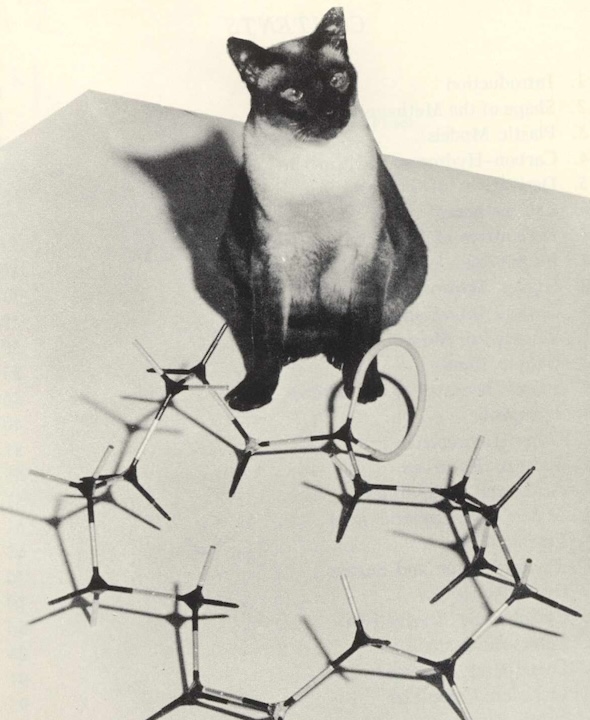

Perhaps the best-known intersection of cats and scientists in our book collection are the works of chemists Mary Fieser and Louis Fieser, who individually and together authored many books and textbooks on organic chemistry. Photographs of their Siamese cats frequently appeared in the prefaces of their books. The Science History Institute also has a delightful and intimate archival photograph of Mary hugging one of their cats.

Illustrations of Louis and Mary Fieser’s cats: (top row, left) Experiments in Organic Chemistry, 3rd ed., 1955; (top row, right) Introduction to Organic Chemistry, 1957; (middle row, left) Advanced Organic Chemistry, 1962; and (middle row, right) Chemistry in Three Dimensions, 1963. (Bottom row) Mary Fieser with her cat Georgie (J.G. Pooh), from the Louis Fieser Photograph Collection, 1949–1952.

Speaking of Louis Fieser, in his oral history interview, Gilbert Stork recalls that while Fieser could be difficult, his love for cats revealed a softer side: “He liked cats, which is a positive sign . . . So he was obviously capable of empathy, if he wanted to.”

And in his oral history interview, chemist Constantine Anagnostopoulos, who studied under Louis Fieser at Harvard University, surmised that his wife’s love of cats may have endeared him to Fieser: “The other thing was that Professor Fieser was—as his books always indicate—a lover of cats, and my wife [Malika Sesi] was also a lover of cats. There was that relationship as well. He might have favored me.”

Our oral history collection includes other anecdotes about cats and the scientists who loved them. Cyril Norman Hinshelwood, under whom Keith Laidler studied at Oxford University, “was a great cat lover. He always had a cat in his room in Oxford and went to great lengths to feed it . . . He enormously enjoyed his cats. He painted. His rooms were lined with his own paintings, some of them of cats.”

And Hubert Alyea, who met Svante Arrhenius while studying in Sweden, recalls the bond between Arrhenius and a cat that reminds me of the one considering mischief in The Alchemist in His Laboratory painting above: “Arrhenius lived right next door [to the lab], and he would come in twice a day . . . He had a cat, who came in with him each day. She loved to wind in and out of all the delicate apparatus and look up triumphantly when she got to the end without knocking anything over.”

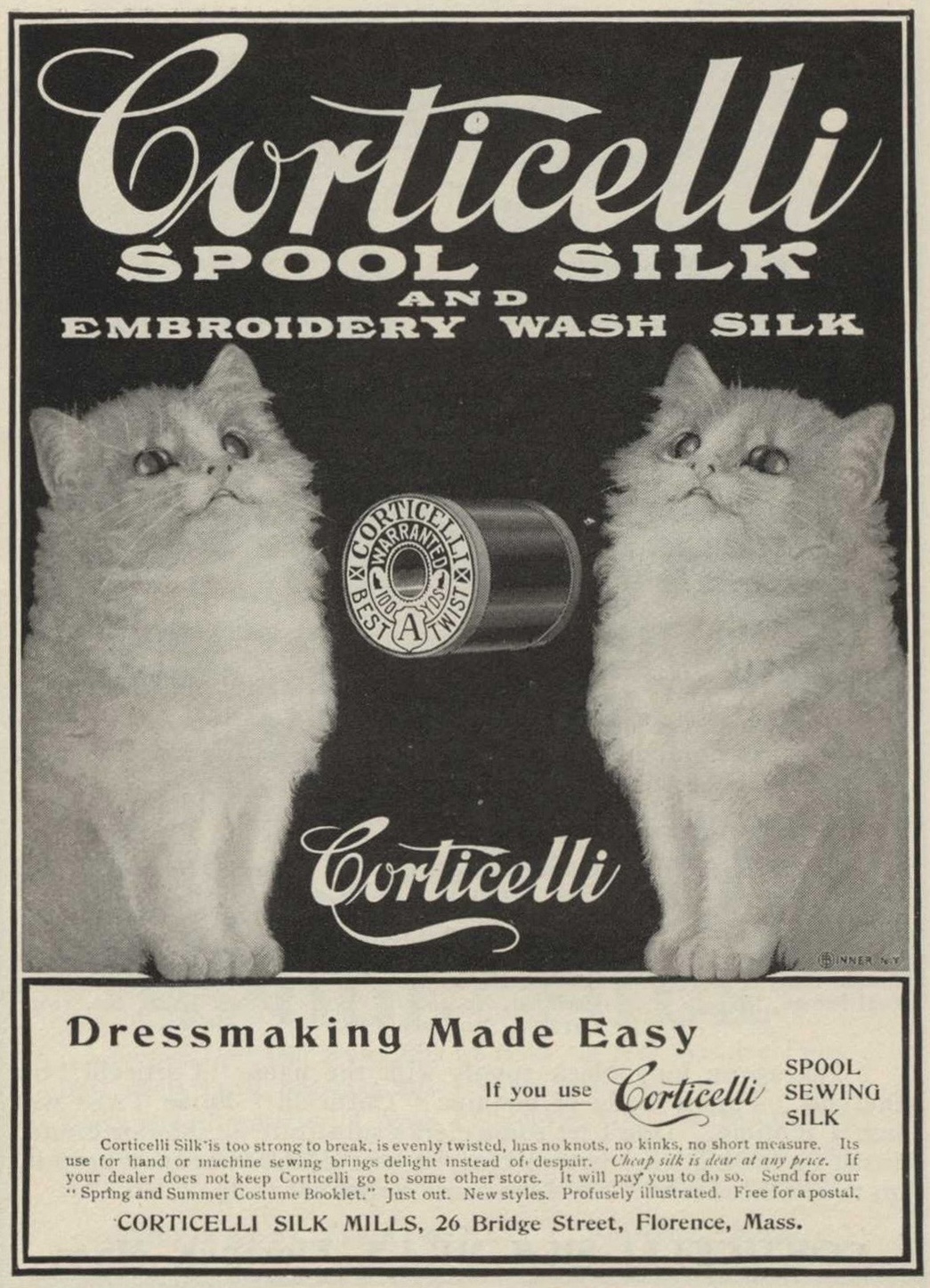

From our 21st-century perspective in which cat images, videos, and memes rule the internet, the use of cats in advertising—particularly when the product has nothing to do with felines—is a familiar phenomenon. I was surprised, however, to see how frequently “catvertising” appeared in our collections. As the examples below show, cats and kittens have been used to market products ranging from silk thread to camera lenses and scientific instruments.

These are just a handful of cat-themed advertisements, most culled from the pages of the journals in the library’s collection. No doubt there are many more to find, hidden in the pages like a cat who knows it is time to go to the vet.

Catvertisements from The Photo-Miniature, volume 3, no. 34, 1902 (left) and Modern Plastics, volume 39, no. 11, July 1962 (right).

The ad for a Collinear camera lens promises that the lens is “quick as a cat.” The ad also draws on the association of cats with exceptional eyesight, as does a 1962 ad for a vinyl developed by Argus Chemical Company.

I wish I knew the story behind the Argus Chemical Company’s use of a Siamese cat in its logo and many advertisements, but so far I’ve been unable to find the connection.

What do kittens have to do with glass bottles? Who knows, but they sure are cute.

Better yet, use polystyrene containers, which won’t shatter when your cat clears the table!

Whoever designed this 1963 ad for the Beckman Instruments Dynograph recorder must have known that Siamese cats are known for their chattiness.

Perhaps the message of this ad is that vinyl strapping is so wonderful that even cats will find it superior to yarn?

This ad for a fabric finishing product recalls the “cats-as-murderers” motif, referring to this sweet little tuxedo as “Carnivora.”

The Corticelli Silk Company frequently used kittens in their advertising, likely because they appealed to the female purchasers of thread and textiles.

Catvertisements from Silk: Its Origin, Culture, and Manufacture, 1902.

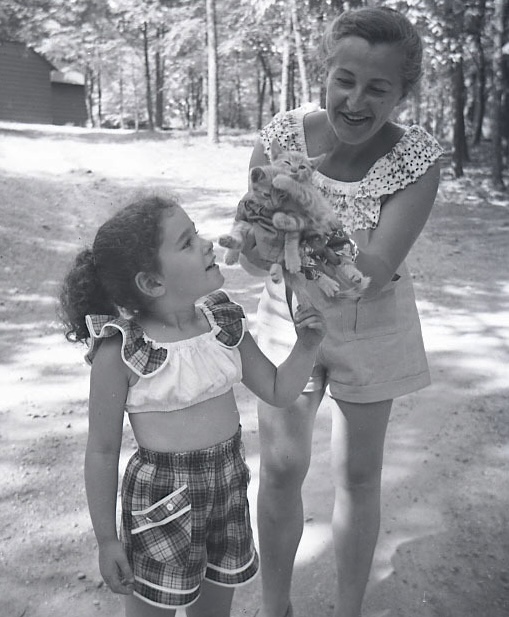

We’ve seen a lot of collection cats, but I’ve saved my favorite for last: a photograph of Gabor Levy’s wife, Friedel, and daughter, Margaret, carrying two (maybe three?) orange kittens. The setting—tall trees, dirt path—and their attire make me think they are on vacation. They look warm, relaxed, and happy. That’s how I feel when I’m holding kittens, too.

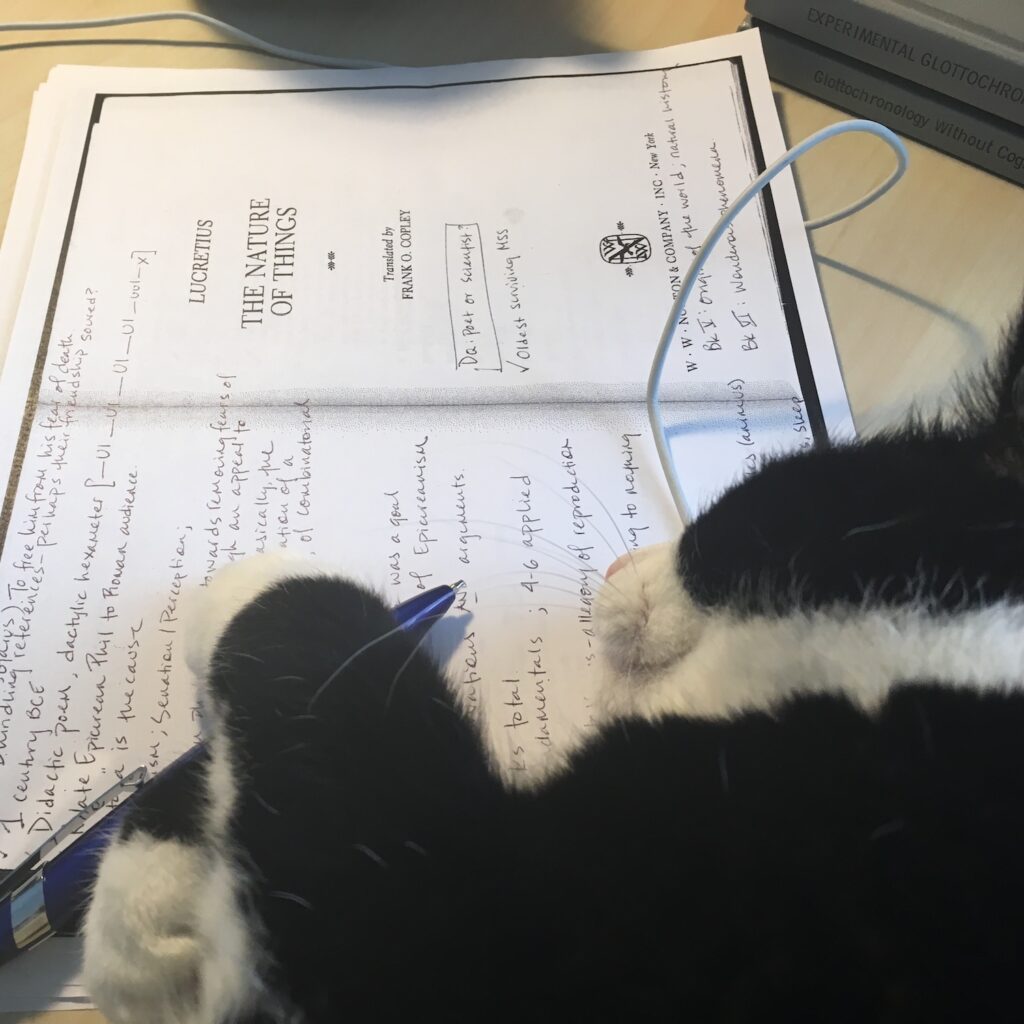

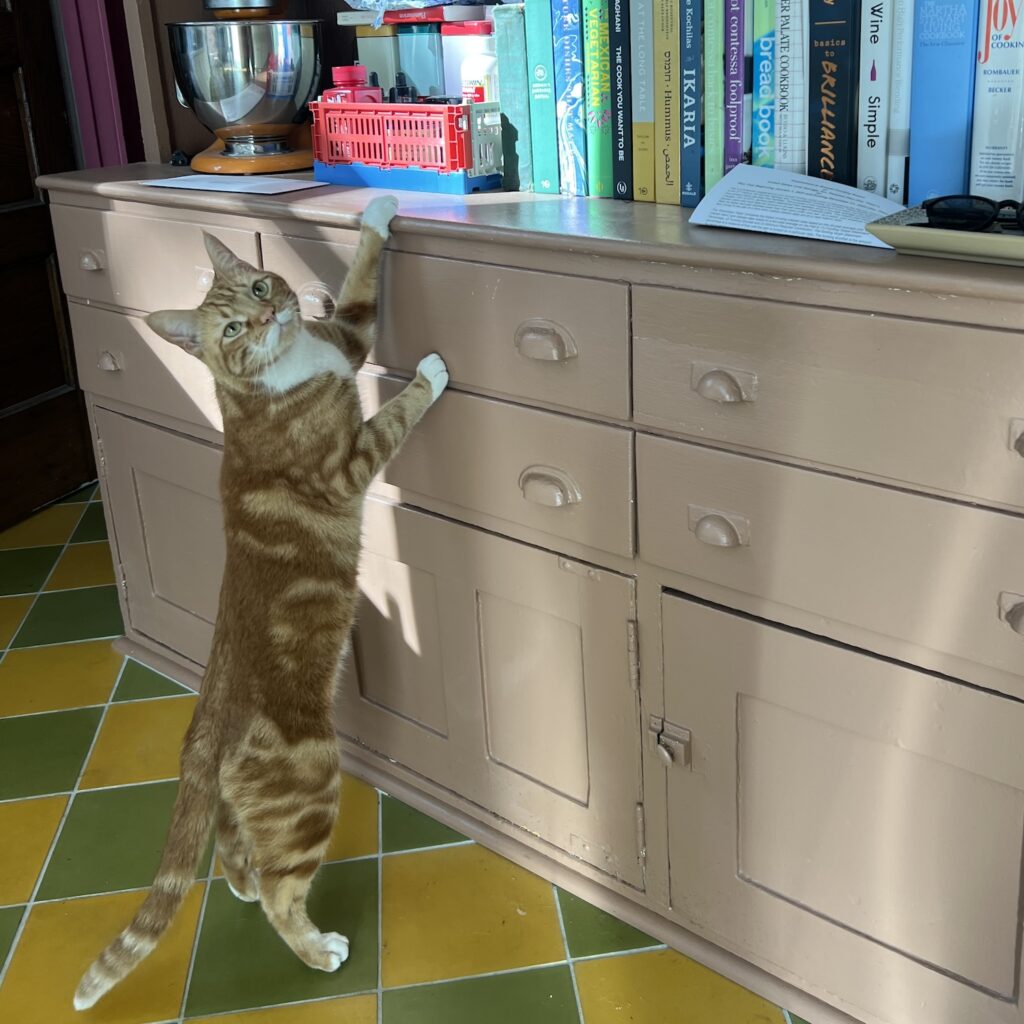

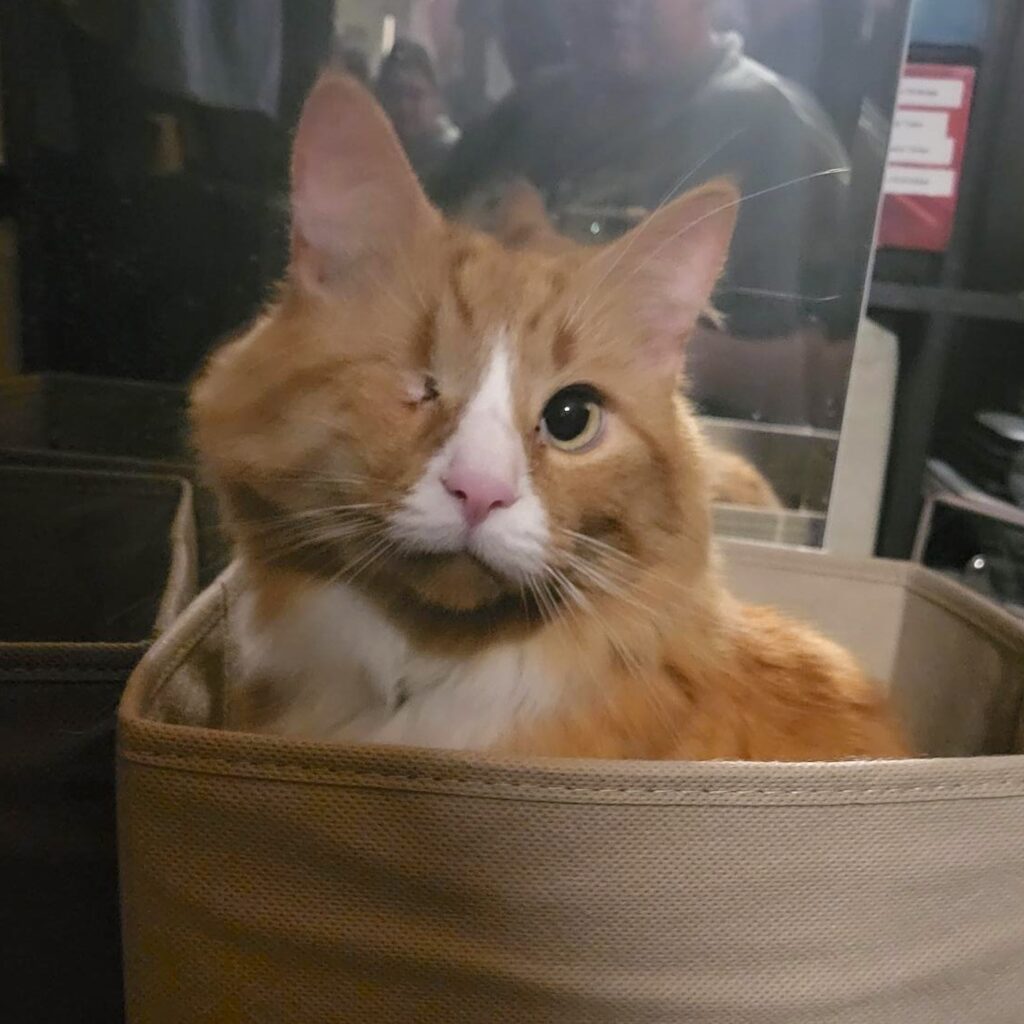

And finally, I couldn’t write about collection cats without including the cats that share the lives of the librarians, archivists, museum workers, and other staff members from every department at the Science History Institute!

Featured image: Detail of a catvertisement from Modern Plastics, volume 39, no. 8, April 1962.

The Institute’s museum education team partners with Philly Touch Tours to offer a more meaningful history of science experience.

Mapping Philadelphia’s industrial past with digital tools.

Memory, materials, and the history of science in the Eugene Garfield Papers.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.