It’s Written in the (Word)Stars

Recovering a scientist’s journal entries from obsolete digital files.

Recovering a scientist’s journal entries from obsolete digital files.

I often like to explain my job as a digital archivist by comparing it to what an analog archivist does (simplified):

Step 1: Receive a collection of papers from a donor.

Step 2: Open a box within that collection.

Step 3: Review the papers inside.

Step 4: Put the papers in order (what order that is depends on a lot of things, such as the context and content of the collection, professional archival standards, and the time the archivist can spend on the collection).

Step 5: Write a finding aid or collection description so researchers know what’s in the box.

The catch for digital archivists is that sometimes we get stuck at step 2: we can’t open the “box”—i.e., the floppy disk, the CD-ROM, the folder, etc.—and if we don’t open it the correct way, we might destroy the contents. (Imagine a hacking scene mashed together with a bomb defusing scene from a ’90s action film.) Maybe we can’t open the box because our hardware or software doesn’t recognize the disk or drive, and so our computer can’t even see the box. Or—surprise!—a donor encrypted something and the archivist can’t get in. Or a file format is so old that the archivist’s modern software can’t open it.

The challenge of trying to read old files with contemporary software is one I faced while working with the born-digital materials in the Kenneth R. Shoulders Papers. Shoulders was an omnivorous and prodigious electrical engineer. He worked on 1950s computers, microelectronics, aerospace projects, experimental aircraft (a helicopter backpack! personal flying cars!), and what he believed was a new source of energy: “Electrum Validium” (EV) or “Exotic Vacuum Objects” (EVOs).

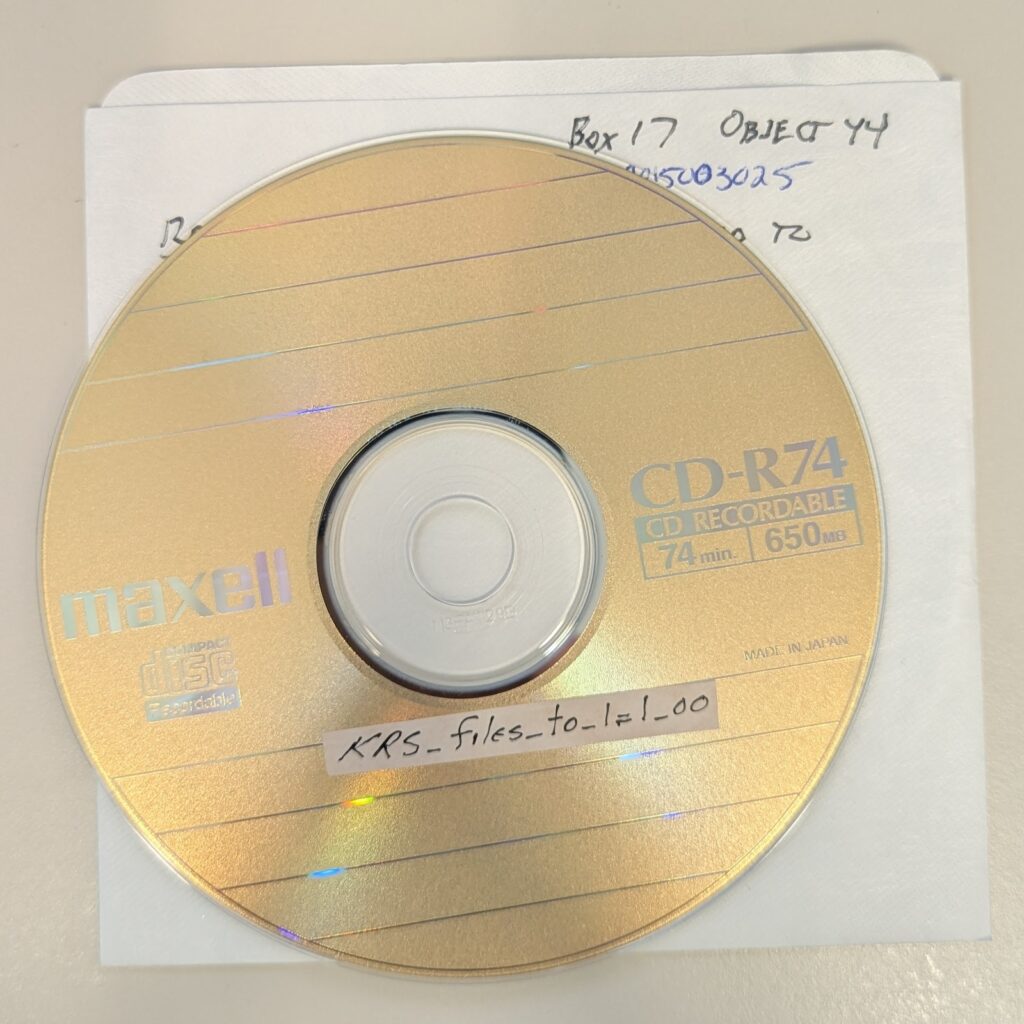

The floppy disks and CDs in Shoulders’s papers mostly contain documents and data related to the EV portion of his career, from the 1980s through the early 2000s. And this is where I found some unopenable boxes.

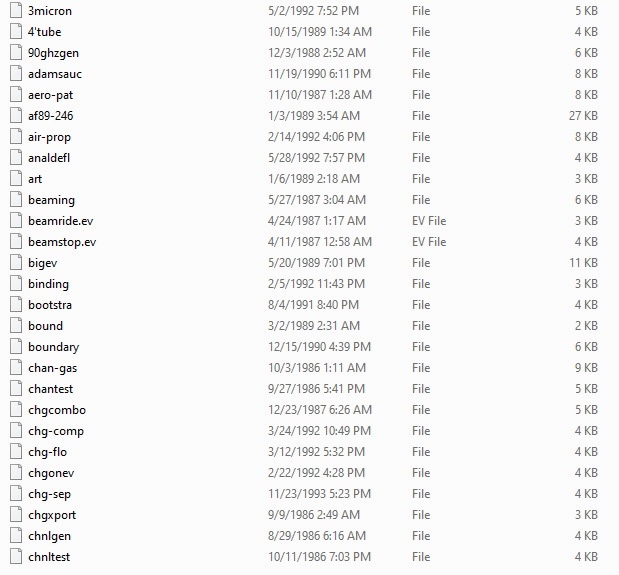

This is a box:

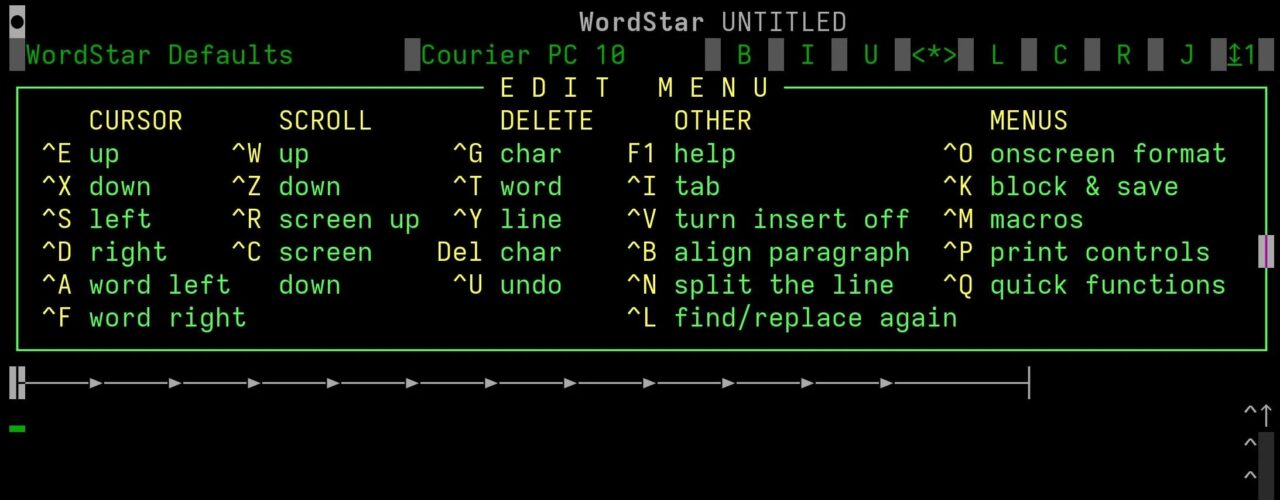

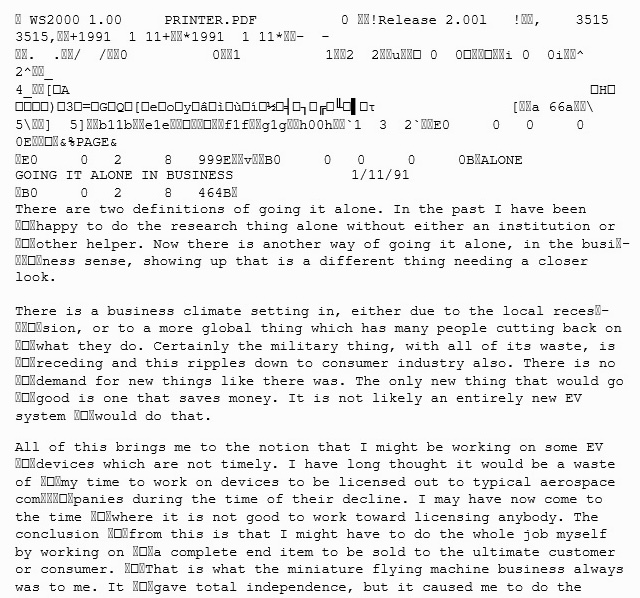

And this is the lock:

The contents of these files are locked behind an unknown file format. Usually, a digital file will end in a three-character string called an extension that tells you (and your computer) what kind of file it is and what kind of software created it, such as .docx for a document made using Microsoft Word, or .jpg for a digital image.

But these files are missing an extension (except for two with the mysterious extension “.ev”). There’s no easy clue about what format they are. Fortunately, there’s a tool for figuring this out: Siegfried. Siegfried is often the first step in working with born-digital archives—it looks in a file’s hex code for a “byte signature” that can help identify the software that created the file. (For more about how Siegfried works, see this excellent blog post from its creator, Richard Lehane). And so by running Siegfried on the contents of this disk, I learned that these are all WordStar files.

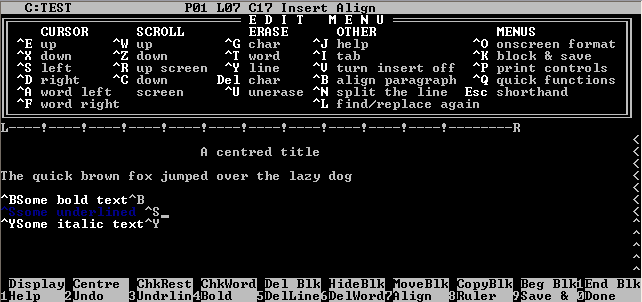

WordStar was a word processing software popular from the late 1970s through the 1990s. It was especially beloved by science fiction and fantasy authors. Michael Chabon, Arthur C. Clarke, George R. R. Martin, and Anne Rice all sang its praises, and author Robert J. Sawyer is keeping the flame alive on his own website.

WordStar let users enter formatting commands in line with the text (see the “^B” and “^S” above). These would be visible on the screen but disappear and be rendered as styling or formatting when the document was printed.

WordStar also did not require files to have an extension, and in fact encouraged users to create their own extension that contained information about what was in the file—like “.LET” for a letter or “.REP” for a report—but told the computer nothing about the file’s format and how to open it. This explains both the lack of extensions on these files and Shoulders’s use of “.ev” as an extension for files about Electrum Validium.

But these file extension quirks are a problem, because modern word processing software (such as Microsoft Word) will actually open a WordStar file, but only if it has a “.ws” extension.

So the second step in making these files accessible was to use ReNamer to:

With that, I could actually open the files!

As you can see, WordStar files open imperfectly in Microsoft Word. The top of the page contains a lot of information that would be meaningful to WordStar, but that Word interprets as gibberish. There are also junky-looking symbols throughout the text, which are likely where Shoulders entered a formatting command, such as a line break, that the software also doesn’t know how to read.

That said, this is a good step toward accessibility. We’ve gone from a locked box with who-knows-what inside to an openable file in which we can actually read Shoulders’s words. And some of that slightly garbled information in the header is useful, like the version of WordStar and the date the file was created.

However, even though modern word processors will open .ws files today, in 2025, it’s extremely likely that they will stop doing so in the future. That’s why I decided to convert these .ws files into a stable format that has a greater chance of being accessible in the future, such as PDF. (PDF has the added benefit over .doc or .docx of being less easily editable, so there’s a much lower chance a researcher will accidentally change a file while looking at it).

The issue with doing that is (as always) scale.

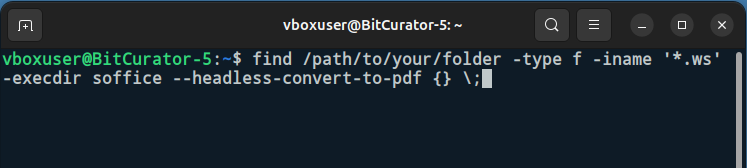

There are more than 1,300 WordStar files on this disk alone, so converting each into a different format one at a time isn’t an option because of how much time that would take. Enter LibreOffice, the Swiss Army knife of digital document management. With LibreOffice, I can type a command into a terminal or command prompt and tell it to do something to a lot of files, all at once. For example, I can tell it to convert all of them into PDFs.

Within 30 minutes of running this command, I had 1,300 newly accessible PDF files, ready for me to investigate so they can be described in a finding aid. That way, researchers will know what we have and, more importantly, the files will be ready for those researchers to study.

These WordStar files are a great example of the balancing act digital archivists do. We try to:

This balancing act usually requires some compromise, and digital archivists often hedge our bets by also keeping the original files, unaltered (as I did with the WordStar files). This way, we’re ready for both the tech-savvy researcher who wants to run WordStar in a DOS emulator or the scholar who just wants to get at the files’ contents in the friendly context of a PDF. And I have to think that inventor extraordinaire Ken Shoulders would appreciate the chain of tools, devices, and discoveries that it took to get us here.

Featured image courtesy of r/vintagecomputing.

The Institute’s museum education team partners with Philly Touch Tours to offer a more meaningful history of science experience.

Mapping Philadelphia’s industrial past with digital tools.

Memory, materials, and the history of science in the Eugene Garfield Papers.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.