Look, Up in the Sky! It’s a Meteor Shower! It’s an Aurora! It’s Super Cloudy!

When bad weather eclipses celestial sightings, our collections can save the day.

When bad weather eclipses celestial sightings, our collections can save the day.

I’ve always lived in or near a big city, so I never gave much thought to the sky, probably because I could barely see it. But in the last few years, I have become a bit obsessed with witnessing every celestial show and cosmic phenomenon under the sun. So now that my son and daughter are older, instead of theme parks, water parks, and amusement rides, my (kid-free, dog-friendly) vacations revolve around sunsets, eclipses, meteor showers, planet parades, and northern lights.

Except all I’ve seen are clouds. Lots and lots of clouds.

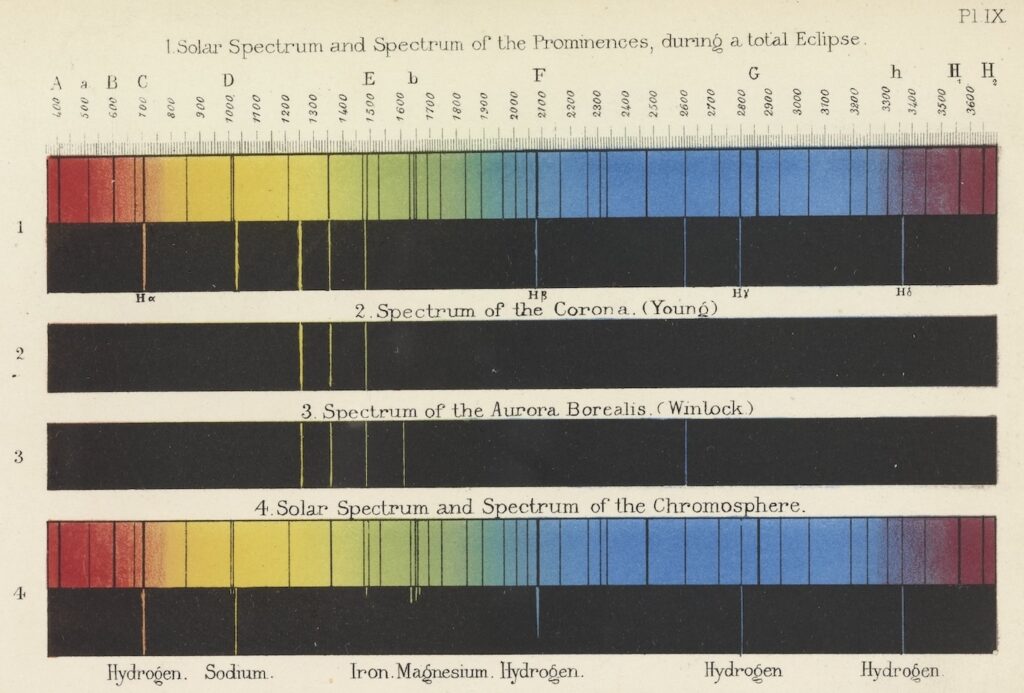

The aurora borealis—or northern lights as they’re more commonly known—is a “natural light display caused by electrically charged particles from the sun colliding with gases in Earth’s upper atmosphere near the north magnetic pole.”

These collisions result in stunning auroras like the one below from the cover of Chemistry Connections: The Chemical Basis of Everyday Phenomena (2003), a second edition reference book found in the Science History Institute’s Othmer Library. I could look at images like this all day, but I’d much rather see one of these dazzling light shows in person so I can check it off my bucket list.

I tried to achieve that bucket list goal in 2023, when my aurora fever led me on a road trip to Michigan’s Headlands International Dark Sky Park where the northern lights can often be seen. Northern lights in Michigan: who knew? Although the park and the surrounding areas around the Great Lakes were breathtaking, I did not see any auroras.

I saw clouds. Lots and lots of clouds.

The following year was (of course) a peak year, producing strong auroras that were visible much further south than usual because of a significant increase in solar activity. I remember my news and social media feeds being flooded with incredible images of the northern lights from around the world—especially from Michigan—and from places where you can’t normally see them, like New Jersey where I live.

What did I see this time? Clouds. Lots and lots of clouds.

A total solar eclipse happens when the moon passes between the sun and Earth, completely blocking our view of the sun and darkening the sky as if it were dawn or dusk. Did you know that there are two to five eclipses per year, with a total eclipse taking place every 18 months or so? I did not; I thought these awe-inspiring events were less common than that. I also did not know that total eclipses are only visible from the same place on Earth once every 375 years on average.

Having to wait almost four centuries to be in the path of totality again is likely why the total solar eclipse of April 2024 caused such a frenzy across North America. The Institute joined the eclipse mania here in Philadelphia with a First Friday “Celestial Celebration” that set a record for attendance in our museum. We even had custom eclipse glasses made so our visitors could safely view it.

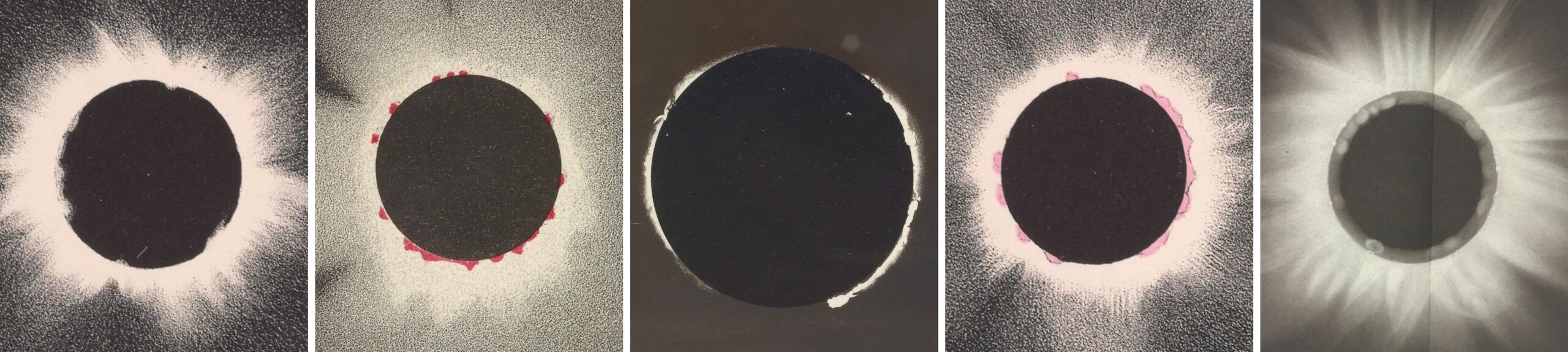

Various images of total solar eclipses from the late 1800s. Let’s hope the photographers didn’t look directly at the sun while taking these!

Unfortunately, I waited too long to plan a total eclipse getaway, so I had to settle for a partial view from my deck. There I was, sporting my official Institute glasses, looking up at the sky. And just as the moon was about to block the sun . . .

Yep, you guessed it. Clouds. Lots and lots of clouds.

Once again, my feeds were inundated with amazing photos and news of what a clear view everyone in the path of totality had. Places like Cleveland, where the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame hosted a four-day SolarFest while “Here Comes the Sun,” “Bark at the Moon,” and “Total Eclipse of the Heart” streamed under a cloudless sky. The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame: the very same museum I had visited the year before on my way to Michigan.

Sigh.

“Most people, at one time or another, have seen what looks like a star shoot right across the sky, and disappear. On a clear starlight night you may often see one or more of these bright lights flash through the air; for one falls on average every twenty minutes . . . these bodies are the ‘meteors,’ or the ‘falling stars’ . . . [they] are not really stars . . . they are simply stones or lumps of metal flying through the air, and taking fire by clashing against the atoms of oxygen in it.”

This description of a meteor shower is from the Institute’s copy of The Fairy-Land of Science (1883), a collection of 10 children’s lectures by writer and science educator Arabella Burton Buckley. And she is mostly correct: I have at one time seen a “falling star,” but not another.

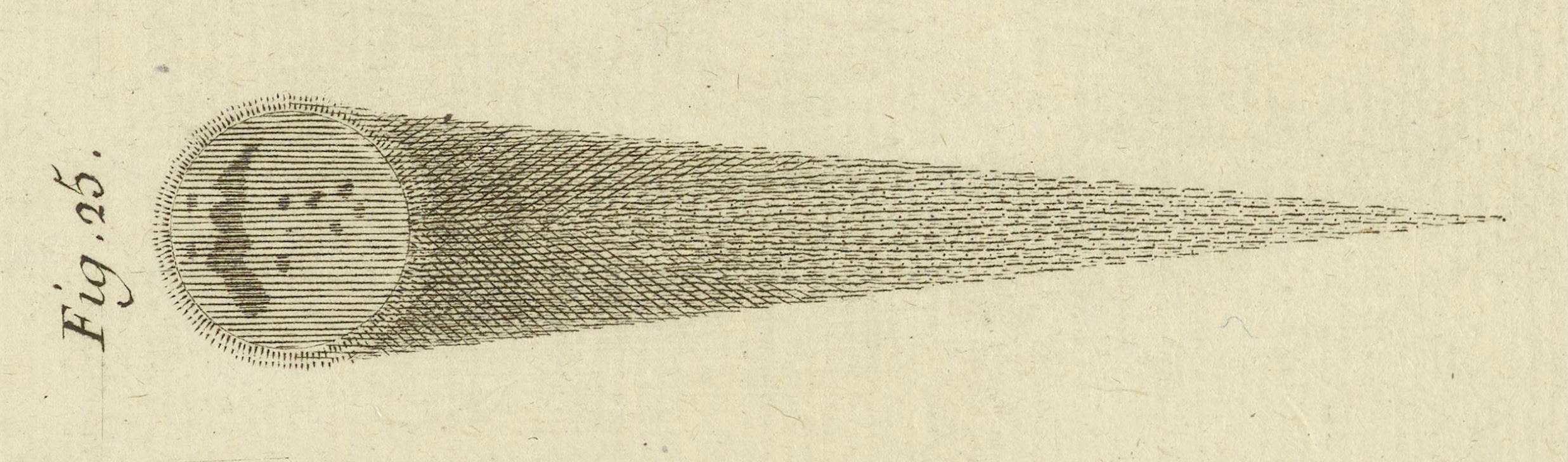

Plate II: Figure 25, illustration of a comet from the “Astronomie” section of Volume 5 of Recueil de Planches, sur les Sciences, les Arts Libéraux, et les Arts Méchaniques, avec leur Explication (1767), which consists of illustrated plates to accompany the volumes of text from Denis Diderot’s Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers (1751-1780).

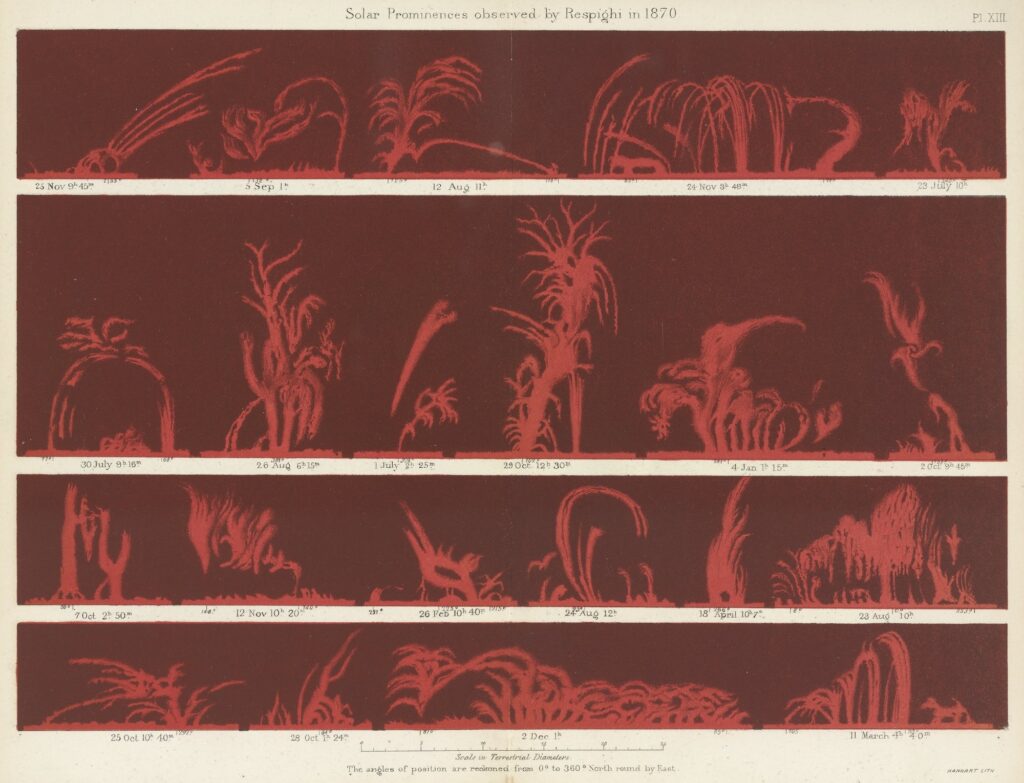

While some meteor showers are caused by asteroids, most are caused by comets, which leave behind a trail of icy and dusty debris in their orbits around the sun. When Earth passes through this debris stream, the small particles burn up in our atmosphere, creating the streaks of light we see as a meteor shower.

Named for the constellation Perseus, the Perseid meteor shower peaks every August when Earth travels through Comet Swift-Tuttle’s dust and rock trail. My news feeds promised that despite a nearly full moon this year, I would still be able to see around 10 to 20 meteors per hour and maybe even a few “fireballs,” which are exceptionally bright meteors. So off I went on a last-minute trip to the Pocono Mountains in Pennsylvania, where the skies are much darker, and saw . . .

Clouds. Lots and lots of clouds.

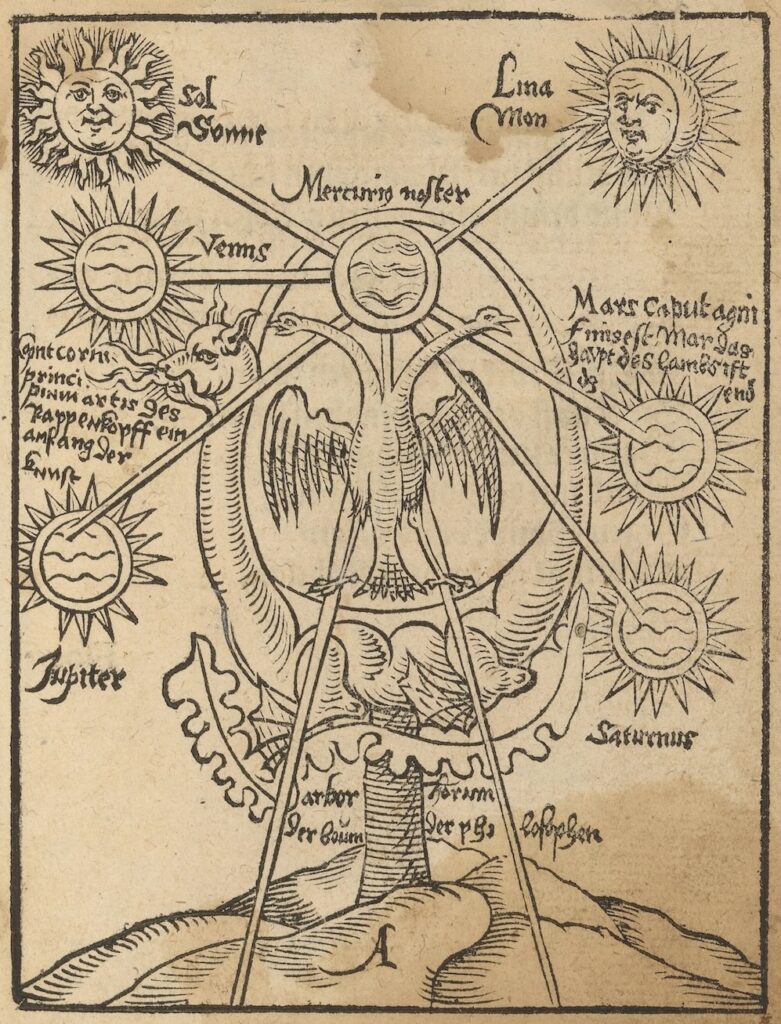

My news feeds also promised I would be able to catch a “parade of planets” at the same time as the Perseids. This rare six-planet alignment of Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune was supposed to be visible just before sunrise in the eastern sky.

All I saw were clouds. Lots and lots of clouds.

A Google search for “what do you call a person who loves sunsets” returned the word “opacarophile,” which I definitely am. Maybe even a super opacarophile. Derived from opacare (Latin for dusk) and phile (Greek for love), it’s pronounced “oh-PAK-uh-roh-file.” I’ve been repeating it over and over since learning there is an actual term for my sunset obsession.

To be fair, I love sunrises, too. But there’s something magical about the moment the sun slips silently beneath the horizon, especially over a body of water. Just look at the fiery scene created by the sun reflecting off the water in the ad above. It’s even more magnificent to see in person.

And I can see it in person often thanks to my recent discovery of North Cape May, New Jersey (emphasis on north), a mainly residential community right on the Delaware Bay that boasts some of the most beautiful sunsets I’ve ever seen. Only 90 minutes from my house, this quiet bayside town has become an annual vacation destination, where I can live my best opacarophile life and experience a gorgeous—and always unique—sunset every day from the dog-friendly beach.

Plot twist: clouds actually enhance sunsets. Significantly.

Similar to water, clouds act as a reflective surface for sunlight, providing a canvas for stunning displays of red, orange, pink, and sometimes even purple. These vibrant hues create dramatic vistas that contrast with the sky’s backdrop. My favorite part might be all the striking colors you continue to see well after the sun has set.

I’m writing this post while sitting on the front terrace of my North Cape May rental, which is directly across the street from the bay. It’s the last day of my 2025 trip and the weather has been pretty perfect all week: partly sunny, highs in the 70s, lows in the 60s, and breezy. The sunsets have been incredible all week, too, but the one above from my first night was truly spectacular.

The reason? Clouds! Lots and lots of clouds!

Featured image at top: Detail of Time, Space and the Balance Sheet, Hercules Powder Company advertisement featuring an illustrated depiction of the solar system, 1930.

The Institute’s museum education team partners with Philly Touch Tours to offer a more meaningful history of science experience.

Mapping Philadelphia’s industrial past with digital tools.

Memory, materials, and the history of science in the Eugene Garfield Papers.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.