Rama IV—more commonly known as the king from the Broadway musical The King and I—had a great love of science including astrology. His passion for the sciences was partially fueled by his fight to keep Siam more modern in the face of encroaching colonialists, but this passion may have led to his untimely death.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineering: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

For most of history, humankind has been absolutely terrified of eclipses. The Vikings, the Mayans, the ancient Chinese—they all trembled in fear. And understandably so. Imagine the sun being blotted from the sky with no warning. I’d be terrified, too.

Many cultures had taboos surrounding eclipses. In some cases, pregnant women had to stay indoors. And people often banged on pots or drums to scare away the mythological wolf or snake or dragon they imagined was devouring the Sun. Some people even shot flaming arrows into the sky to reignite the sun.

Moreover, natural disasters like earthquakes have long been linked to eclipses. As have untimely deaths. Famous historical deaths that have been linked to eclipses include Charlemagne, King Henry I of England; the Prophet Mohammad’s son Ibrahim; and Jesus of Nazareth, as the land was cast into darkness during his crucifixion.

Nowadays we’re likely to dismiss the link between eclipses and death as superstition, or the thinking of pre-scientific minds. There’s no way watching an eclipse could kill someone, right?

Well, not so fast. I’ve written before about how the element helium was discovered during an eclipse in August 1868. But among astronomy buffs, that eclipse is known as the King of Siam eclipse. That’s because it led to the death of the king of Siam. His name was Rama IV, and he’s best known from the musical The King and I.

But if the eclipse killed Rama IV, it also had another, bigger effect on Siam overall. The king may have perished. But his deep love for astronomy ended up saving the kingdom itself from destruction.

Rama IV was born in Siam—modern-day Thailand—in 1804. The young prince was groomed for the throne from an early age, and by all accounts, he enjoyed the royal life. He lived in a palace and fathered two children with concubines during his teenage years.

Then, he gave it all up, at least temporarily. At age 19, he entered a monastery. He became a Buddhist monk and renounced his former life.

You see, joining a monastery was simply a common thing for young men to do then—a way to teach them humility and discipline. And it wasn’t permanent. He had to endure the monk lifestyle only until his father the king died. Then he could resume his former life.

Except, life swerved on him. His father died in 1824, just months after Rama joined the monastery. But instead of allowing Rama to ascend the throne, royal advisors passed over him. They promoted his thirty-six-year-old half-brother instead.

Rama could not have been happy with this. Not only had he been passed over, but he now had to remain a monk. Which meant begging for food, renouncing all worldly possessions. Quite a downfall for a prince! He couldn’t even talk to women now.

Rama endured this life for the next twenty-seven years. But, being ambitious, he made the most of the time. He helped reform religious orders in Thailand, instilling discipline and tightening standards. He also began studying European languages and cultures. He did so because Great Britain and France were beginning to colonize southeast Asia, and he wanted to understand the colonizers. Along those same lines, he began studying astronomy.

As an ancient kingdom, Siam had its own cosmology, including constellations. What we call Ursa Major, the great bear, they called the crocodile. They also used the stars to cast horoscopes, plot out their calendar, and determine the dates for religious holidays.

Unfortunately, Rama soon realized that the monks in charge of the calendar were using outdated techniques to do all this. This led to poor and inaccurate results. Christian Europe had actually experienced similar problems until about 1600.

So Rama decided to fix things. He began reading up on scientific methods of tracking planets and stars. And he got pretty sharp at this. He eventually revised the Buddhist calendar in Siam, bringing it up to date and rendering it more accurate and stable.

So that’s how Rama spent his time—fasting, praying, studying astronomy, and waiting to become king.

After nearly three decades of this, he must have seriously wondered whether he would ever rule Siam. Especially with his iffy health. Pictures show him looking thin and weak and white-haired. He lost all his teeth. He also suffered a small stroke, which caused the right side of his face to droop.

Finally, though, in 1851, Rama’s half-brother died. At age 46, he ascended the throne as Rama IV.

And to be frank, he made up for lost time. He held an elaborate coronation, and built several sumptuous palaces. And after 27 years of celibacy he took multiple wives, along with many, many concubines. The concubines actually lived in a small town separate from the rest of the population, complete with their own female-run police force and prison. Rama eventually fathered 82 children over all.

Meanwhile, Rama began the serious job of running Siam. One big concern was keeping Siam independent. British and French colonialists were closing in on all sides, eager to carve the country up.

Perhaps to win allies against the French and British, King Rama wrote a letter to U.S. president James Buchanan in 1859. In the letter, he offered Buchanan a gift: a pack of Siamese elephants. He thought they could be let loose on the plains of America and trained as beasts of burden.

The letter took so long to arrive that it was not Buchanan but his successor, Abraham Lincoln, who actually received it in the White House. Lincoln joked about using the elephants to “stamp out the rebellion” of the Confederacy. But he ultimately told Rama that the climate in America didn’t seem right for pachyderms.

Beyond international affairs, Rama faced the domestic challenge of how to educate his many, many children. As noted, he was greatly impressed with Western science, especially astronomy. And he wanted his children exposed to Western ways and ideas, partly to better resist colonization. Know thy enemy. So he began scouting around for Western tutors.

He found plenty of candidates—but swiftly rejected every one of them. You see, most Westerners in Southeast Asia then were missionaries. And Rama did not trust them. He knew they’d try to convert his children to Christianity on the sly, which would undermine the kingdom. He admired Western science, but didn’t want to abandon traditional ways.

After an exhaustive search, he finally found the perfect tutor—Anna Leonowens, a young widow. She ran a school, and promised to focus on education, not preaching the gospel.

The relationship between Anna and Rama became the basis of the musical The King and I. And the show’s central struggle involves the clash of two cultures, European and Asian. And the film is considered so offensive in Thailand that it’s still banned today!

In part because the historical truth was far more complicated than the movie shows. In reality, Anna was only half-European. She’d been born in India, the daughter of a British soldier and an Anglo-Indian woman. But she concealed her ethnicity for the rest of her life and told everyone she was Caucasian. Probably to avoid prejudice among British expats in Asia.

Now, Anna’s heritage was not known when the musical was written. So the authors weren’t trying to whitewash her or anything. But it does add a layer of complexity to the story. And possibly because of her background, Anna tutored Rama’s children on Western ways without undermining their traditional values.

With his children’s education secure, Rama kept studying astronomy whenever he could. For example, when British officials visited his court, he quizzed them on the recent discovery of the planet Neptune. I’ve mentioned that story in a previous podcast—how a snooty French astronomer conjured the planet up using nothing but math and shrewd deductions. Rama was blown away.

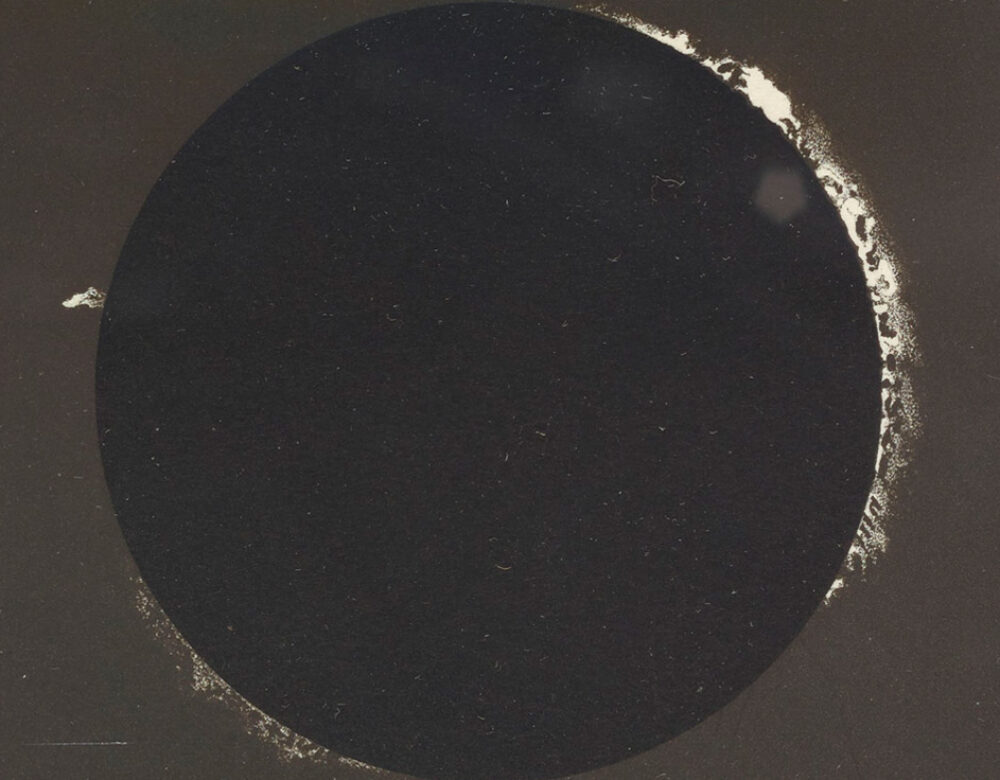

Even more exciting, in 1868, Rama’s kingdom became the center of the astronomical world. That’s because a solar eclipse crossed Siam.

Solar eclipses occur when the moon slides in front of the Sun and blocks it. Hearkening back to his days as a monk, Rama set out to calculate what time exactly this would happen, and how long the eclipse would last in Siam.

Calculations like this were tricky. Rama had to determine the size of and distance to both the Moon and Sun, then calculate their exact path and speed through the sky. There were tons of variables to juggle. And given the vast distances involved, even a tiny mistake could throw the whole result off.

But Rama had learned his astronomy well. He determined that the “shadow cone” of maximum darkness would sweep across the small village of Wakor in southern Siam. He calculated that the length of the eclipse would be 6 minutes, 46 seconds. To check this result, he got in touch with some French astronomers in the region. They told him that he was off by only two seconds in his calculation. Pretty good for an amateur!

Still, not everyone was excited. Royal astrologers actually warned Rama not to go view the eclipse—his horoscope for that day looked ominous.

The big day was August 18th, 1868. The village of Wakor sat between some craggy mountains and low-lying floodplains. It was lush and green and bursting with life. Birds and monkeys—and bugs, my god, the bugs. They were everywhere.

Rama brought his entire kingly retinue down to Wakor. This included his son the prince, dozens of servants, and a train of elephants. In the village, he met a team of French astronomers—plus, the inevitable French and British colonial officials, still eager to carve the country up.

But, any looming international tension was laid aside that day. Everyone simply enjoyed the magic of the eclipse. And magic is the right word. People in Rama’s time could obviously understand eclipses scientifically. But there’s still something enchanting about them. And primal.

Animals chatter and howl in confusion. The temperature plummets. Above all, watching the sun vanish from the sky, you’re truly aware that you’re on a celestial body—on a planet, spinning amid other planets, at unfathomable speeds and distances. Even astronomers forget all their book-learning, and stand in awe before the cosmos.

The Siam eclipse was especially tickling for King Rama. Siam was the center of the astronomical world that month. And it turns out his science wasn’t so bad, either.

Again, he’d calculated that the eclipse would last 6 minutes, 46 seconds. French astronomers had patted him on the back for getting so close to their superior number.

Well, it turned out that the French astronomers were the ones who’d made mistakes. Rama’s number was dead right. The king and former Buddhist monk had outshined the professional astronomers.

Rama and everyone else celebrated the eclipse with a feast afterward. It included buckets of champagne on ice. That might sound standard for a royal feast today, but remember that this was tropical Siam, in 1868. Ice there was unbelievable, a decadent luxury. But Rama spared no expense celebrating the eclipse. It was one of the great days of his life.

Sadly, it would also prove one of the last days of his life. While the scientists and the kings guzzled champagne and listened to the birds chirp and the monkeys chatter, they also had to fight off bugs—including malaria-carrying mosquitoes.

It’s impossible to know when it happened. But mosquitoes are most active at dusk. And given that eclipses produce a false dusk that confuses animals—it’s possible that King Rama got bitten during his eclipse, and because of his eclipse. Regardless, he got bit at some point. Malaria microbes invaded his bloodstream.

He wouldn’t have noticed at first. Malaria takes days to take hold. But when it does, there’s no mistaking it. The quaking chills, the roasting fevers, the bed-drenching sweats. It’s a body-destroying cycle of hot and cold, over and over and over.

Several British and French officials fell sick with malaria as well. As did the King’s son, Prince Chulalongkorn. But while most people pulled through, including the young prince, King Rama did not.

His body was already weak from 27 years of deprivation and hardship as a monk. He ended up dying six weeks after the greatest day of his life. Ironically, Rama’s court astrologers and their horoscopes had proved right—the eclipse had indeed been his doom.

In the end, fascination with astronomy cost the king his life. But in a roundabout way, it also saved his kingdom overall.

Again, during this era, Southeast Asia was being carved into colonies. The British took over Singapore, Burma, and Malaysia; the French took over Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Siam sat smack in the middle of all of them. And you can bet that both European tigers were circling it hungrily.

Ultimately, though, neither country colonized Siam. It escaped. How?

A few reasons. Because Siam sat right between British and French colonies, it served as a convenient neutral territory—a buffer zone that kept these belligerents separate.

But the other big reason was Rama’s passion for science. Whenever he talked to European officials about Neptune, or eclipses, he struck them as very modern, very up-to-date. He seemed more worldly—for better or worse, more like them.

So did his children. Remember that Prince Chulalongkorn had accompanied his father to view the eclipse. This made him seem worldly as well. And Rama had insisted that Anna Leonowens educate his children, so they knew Western ways.

In short, Rama and his heirs impressed the Europeans by playing on their prejudices of what modern leaders should do and say. As a result, they trusted that Siam would play ball when it came to trade and alliances and such. So they left Siam alone. And the kingdom remained proudly independent—one of the few places that was never colonized by European powers.

It’s a truism that science and politics don’t mix well. Politics corrodes the independence that makes science possible, and most politicians simply can’t think like scientists do. But the King of Siam, Rama IV, was adept at both. And when his country was at stake, science proved to be just politics by other means.