The Kids Are Alright

Understanding past attitudes toward science and medicine through children’s books.

Understanding past attitudes toward science and medicine through children’s books.

Today’s blog post features a conversation with science historian Bert Hansen, who talks about the fascinating collection of juvenile biographies of scientists he recently donated to our Othmer Library. Dr. Hansen is the author of Picturing Medical Progress from Pasteur to Polio and has written many articles for our Distillations magazine.

Science History Institute: Professor Hansen, you recently donated about 25 children’s books, mostly from the 1950s and 1960s, to our Othmer Library. Can you tell us why these works are important to the history of science?

Bert Hansen: Admittedly a very modest gift, this small collection calls attention to the large place that the history of science used to have in popular, non-academic reading in the U.S. These books are biographies of scientists, doctors, and other medical professionals of the past. Many of the subjects were famous for discoveries.

Everyone’s heard of Edward Jenner, Louis Pasteur, and Walter Reed. But very interesting people like William Crawford Gorgas and Joseph Goldberger are largely unknown. William Henry Welch, a medical dean at Johns Hopkins, was nationally famous and appeared in 1930 on the cover of Time magazine, but few recognize his name today.

Left: Cover of Prophet with Honor: Dr. William Henry Welch by William D. Crane (Julian Messner, 1966). Right: Cover of William Crawford Gorgas: Tropic Fever Fighter by Beryl Williams and Samuel Epstein (Julian Messner, 1962).

For those mid-century decades, the history of science and medicine occupied significant space in popular culture of all sorts—novels, non-fiction books, Hollywood movies, magazines, and comic books. The field had not yet retreated to a limited space in medical and graduate schools, historical journals, and a few notable centers like the Science History Institute.

SHI: Children’s books are short and don’t have citations, so what can they reveal about someone like Pasteur that’s not known from the original writings and the scholarly literature already in the Othmer Library collections?

BH: Their value, I think, is not for enlarging our picture of the development of science, but in documenting and bringing to light the U.S. public’s feelings and ideas about what science does, what it contributes to society, what kind of people have done science, and how those people became interested in scientific careers. These books bring to life the postwar enthusiasm for scientific progress in U.S. culture and reveal how writers and publishers tried to engage children and teenagers through adventure stories and promises of exciting careers.

Fascinating careers await! Left: Cover of Pioneer Oceanographer: Alexander Agassiz by Beryl William and Samuel Epstein (Julian Messner, 1948). Right: Cover of The Sherlock Holmes of Medicine: Dr. Jospeh Goldberger by Dian Dincin Buchman (Julian Messner, 1969).

SHI: Can you say a little more about this postwar enthusiasm for science? Was there a public consensus around support for science then? That seems to contrast with later decades when we’ve faced persistent beliefs in creationism, an upwelling of anti-vaccine sentiment, several decades of denial of the dangers of smoking and causes of climate change, and questions over the very nature of science.

BH: U.S. science and medicine experienced what you could call a “golden age” from the 1930s through the ’60s, characterized by widespread optimism for scientific progress and public support for funded research. Notable in this context was an expansion of the National Science Foundation’s mandate to support activities at the pre-college levels of school with the aim of increasing the number of students pursuing careers in science, medicine, and engineering.

It would take us too far from these books to describe or account for this golden age, but a few major factors can be mentioned. In medicine we had witnessed a rich hundred years with a continuous flood of discoveries such as anesthesia, antisepsis, the germ theory of disease, and the role of microbes in infectious disease; a new awareness of public health; the discovery of vitamins and hormones; new vaccines; and antibiotics.

Penicillin’s development and deployment in World War II marked the pinnacle of such publicly applauded benefits of research. And then in 1955, America went even more crazy with excitement and gratitude for the successful trial of the Salk polio vaccine.

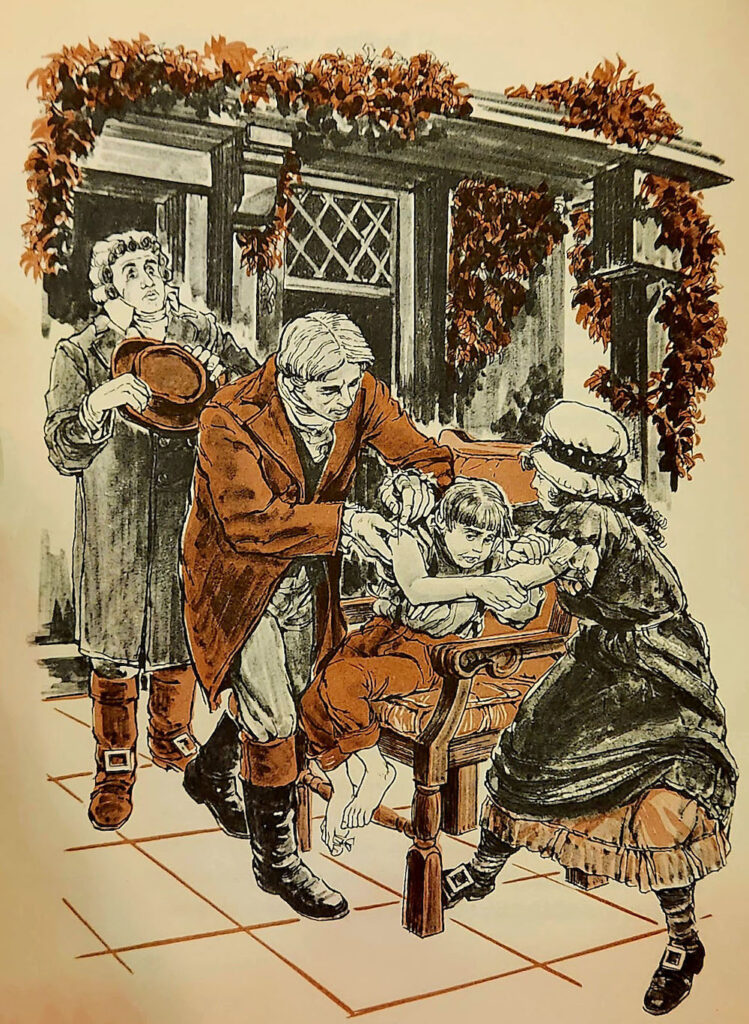

Left: Cover of All About Great Medical Discoveries by David Dietz (Random House, 1960). Right: An illustration from the book showing Edward Jenner inoculating young James Phipps with cowpox taken from lesions on the hands of milkmaid Sara Nelms.

The natural sciences and engineering were also transforming both industry and daily life with fertilizers, air conditioning, commercial passenger flights, radio, technicolor films, and television—and the personal computer was just over the horizon. The atomic and hydrogen bombs brought dissonant and chilling notes to the chorus of enthusiasm, but nuclear science did not quiet our songs of praise for science until popular enthusiasm waned in general in the late 1960s. Then, in 1972, the press’s exposure of research abuse in the Tuskegee syphilis experiments added momentum to a rising skepticism about science as a universally valued enterprise.

SHI: And what do biographies written for children have to do with this period?

BH: I think biography came to dominate non-fiction accounts of science starting in the 1920s. Several factors made this a useful genre for spreading particular values around science. Biography automatically includes change and implies a direction. Biography is inherently optimistic and future-oriented. And perhaps most important here, the story of a single life acquainted young readers with people their own age, and not just with adult scientists who ran around in white lab coats, holding flasks and using multisyllabic words and dense equations.

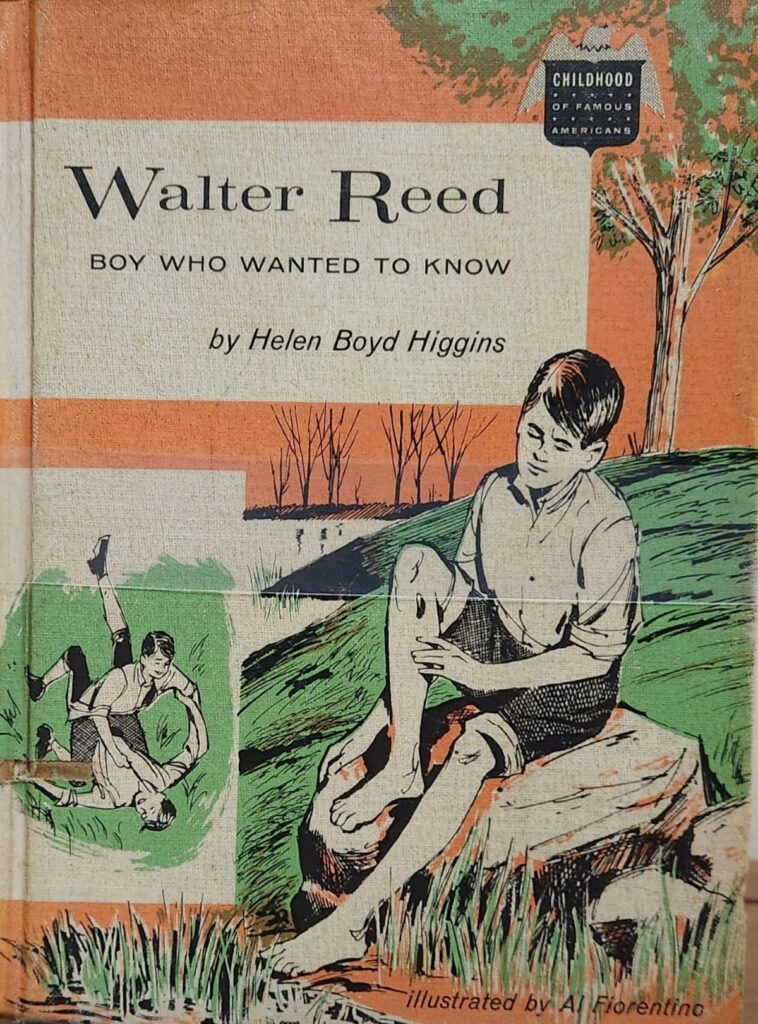

The cover of Walter Reed: Boy Who Wanted to Know shows him seated near a pond, examining the cut on his leg that he received in a scuffle with another boy.

Publishers intended a peer connection to heighten engagement, a way for readers to imagine themselves embarking on a career in science as something familiar.

SHI: As you noted, there are some famous names in this collection, but there are less familiar names, too. Are any of them surprising to you?

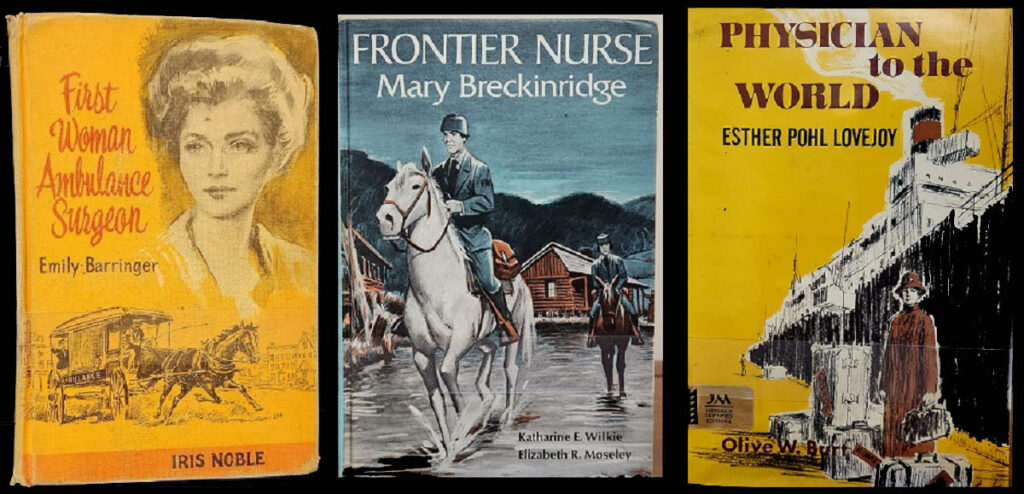

BH: What struck me as I was accumulating these books haphazardly at flea markets, garage sales, and online was finding many more about women than I had expected.

We have stories not only of Dr. Emily Barringer (First Woman Ambulance Surgeon) and Mary Breckinridge (Frontier Nurse), but also of Dr. Esther Pohl Lovejoy (Physician to the World), the leader of the largest organization for women in medicine in the United States.

There are biographies of many other women in health care and science not present in my little collection, such as Elizabeth Blackwell, Ellen Richards, Dorothea Dix, Mary Ann Bickerdyke, Edith Cavell, Florence Nightingale, Ora Ruggles, Lillian Wald, Alice Fitzgerald, Irène Joliot-Curie, Isabel Barrows, Clara Barton, Berthenia Owens-Adair, and one book on four women who won the Nobel Prize.

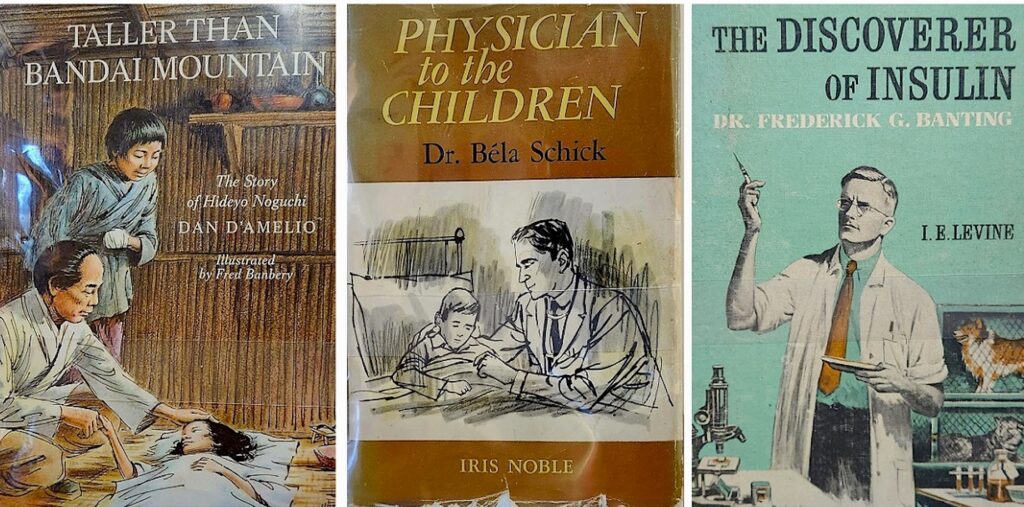

I was especially surprised to find a book about Hideyo Noguchi, a Japanese physician who came to the U.S. for laboratory research at the frontier of medicine in the early 20th century—hardly an expected choice shortly after a brutal war with Japan and years of anti-Japanese propaganda and discrimination in the States.

Works in this little collection also tell the life stories of the Hungarian American physician Béla Schick, who developed a diphtheria skin test that helped wipe out this childhood disease, and the Canadian research doctor Frederick Banting, co-discover of insulin for diabetes.

That era did not have diversity-and-inclusion efforts for the STEM fields, as we do, but the publishers and writers clearly made serious effort to include many women. Unfortunately, I am aware of only three Black scientists who were featured in children’s books like these, and none of these showed up when I was collecting. They are Benjamin Banneker, a mathematician and astronomer in the Revolutionary Era; George Washington Carver, pioneering agricultural scientist of the late 19th and early 20th century; and Charles Drew, who revolutionized blood banking at the time of World War II.

SHI: What kind of research do you envision for these books?

BH: They offer good entry points whether for an undergraduate paper, a graduate student project, or the start of a master’s thesis. As a teacher, I’d suggest first examining the stories themselves, reading to be alert for tropes, themes, morals, and messages embodied in them. Look next at reviews of a sampling to see what story characteristics were noted by contemporary book reviewers. Then search for scholarly or popular accounts, including magazine and newspaper stories of that era, about some of the publishing houses that produced a number of juvenile biographies.

Business journalists may well have reported on trends in publishing, especially for new series. And publishing industry trade magazines may have taken note when a new series was introduced. Then, perhaps as a last step, a search of scholarship on “the public understanding of science” (there’s even a journal with that title) will provide more context for judging the significance of what the student’s research has discovered.

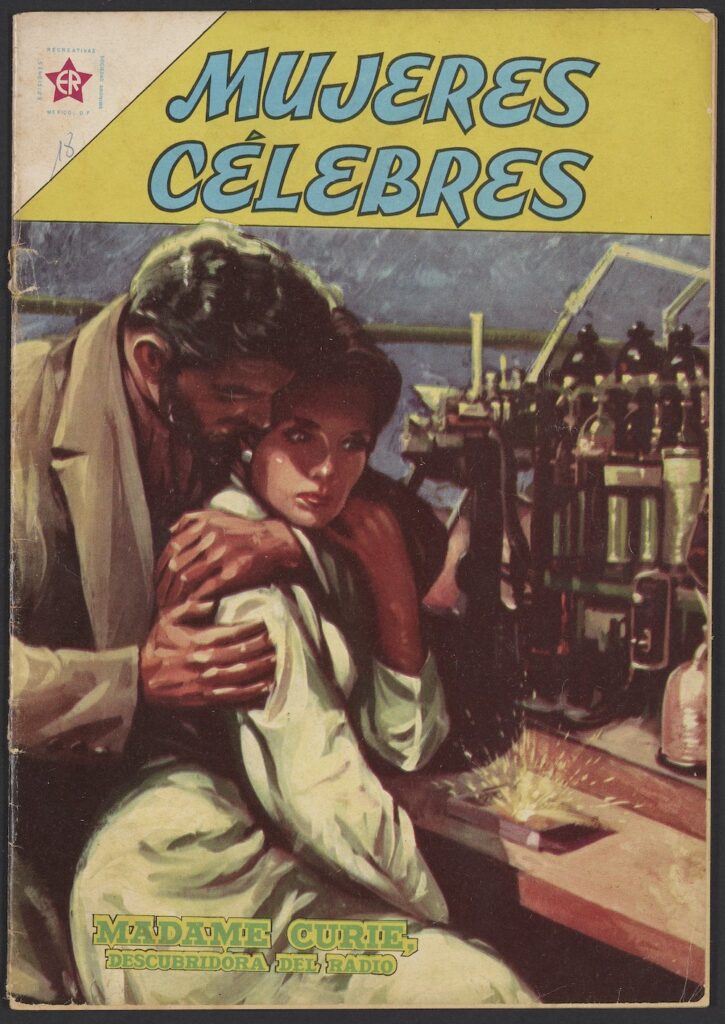

A few years back, Boaz N. Adler and I published a piece in the Institute’s Distillations magazine on science biographies in Spanish-language comic books of this era, working from examples that had been donated to the Science History Institute.

Following that, Adler published a scholarly article titled “Illustrative Lives in Spanish: Mexican Comic Books about Scientists as Inspiration for Science Education” in the fall 2012 issue of the International Journal of Comic Art. Those pieces would be handy starting points for studies on these biographies.

I could say much more, of course, but maybe it’s better to invite readers and researchers to explore these books for themselves, to see what they will discover about mid-century understandings of science. Besides the books here in Philadelphia, many examples are still on the shelves of public libraries around the country, and some have been digitized.

SHI: Any final remarks before we close our conversation?

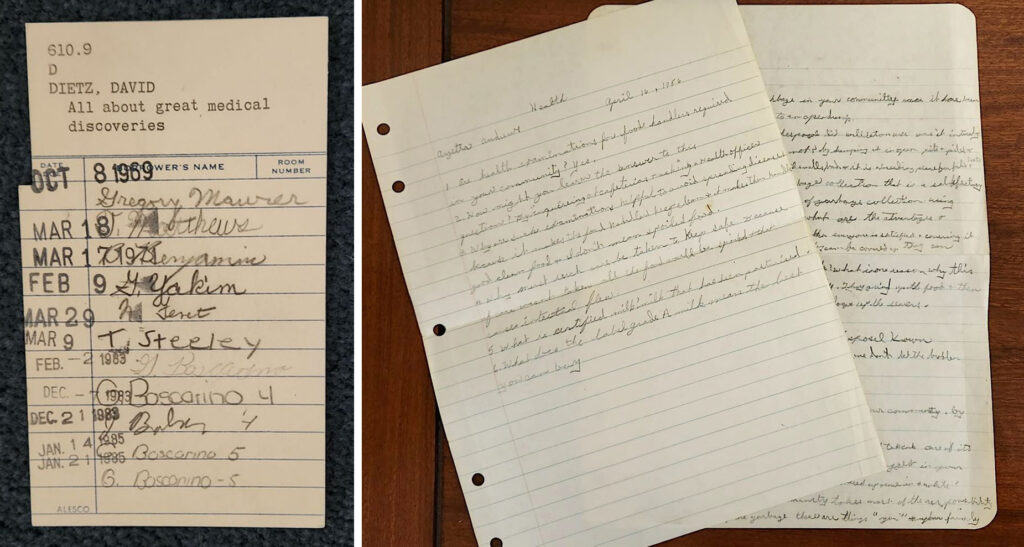

BH: This little collection, though fascinating, is just a tiny sample of what might have been hundreds of books like these. But it’s hard to know, since children’s books are rarely acquired by research libraries. Like comic books, each book was shared among many children until they were discarded and were never preserved systematically.

The books in my donation are humble books with no fine bindings, no pristine copies, no small editions, and no author signatures. But they offer endearing evidence of their use: library markings, check-out slips, school ownership stamps, wear-and-tear, and other signs of their lived history as hand-held inspiration for would-be future scientists.

My guess is that some of our readers may well have similar books on their shelves or in their grandparents’ attic. If they do, I hope they’ll look at them with fresh curiosity and a new pride. And perhaps such items might be offered to the librarians at SHI to see if they are appropriate items to build out this collection.

Many thanks to Dr. Hansen for this generous gift and for chatting with us about his donation. Selections from the collection are on display in the Othmer Library Reading Room through spring 2024. If you are interested in using the collection, please contact the library for an appointment.

Featured image at top: Page from All About Great Medical Discoveries featuring an illustration of French physician René Laennec watching children playing, which gave him the idea for the stethoscope.

Science History Institute

In pursuit of something memorable and meaningless.

How does a museum and library negotiate biography, civics, and the history of science?

Searching for the cats hiding in our collections.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.