The Making of ‘Arrowsmith’

A fraught collaboration ushered a medical classic into the world.

A fraught collaboration ushered a medical classic into the world.

As a summer curatorial intern at the Science History Institute, I spent a lot of time exploring the ways scientific discovery appears in U.S. popular literature through the book collections of the Othmer Library. My work revolved mostly around the writing of Paul de Kruif (1890–1971), a bacteriologist, author, and public health advocate perhaps best known for his collective biography Microbe Hunters (1925), which celebrated the achievements of early microbiologists.

While developing digital educational content on de Kruif for the Institute, I learned about a set of de Kruif books recently donated to the Othmer Library by historian of science and medicine Bert Hansen. The set includes eight copies of a novel de Kruif contributed to called Arrowsmith (1925), an intrigue-filled exploration of the darker side of laboratory-based bacteriology research in the early decades of the 20th century.

Although Arrowsmith is a relatively unknown title today, throughout the 20th century, it dominated as the premiere example of the medical research adventure novel. It follows Martin Arrowsmith, an idealistic, Midwestern doctor-turned-bacteriologist, as he struggles against hypocritical, profiteering doctors and the ethical dilemmas of research plaguing 1920s American medicine. The book taught audiences to regard biomedical researchers as heroes and inspired numerous young readers to pursue careers in science themselves.

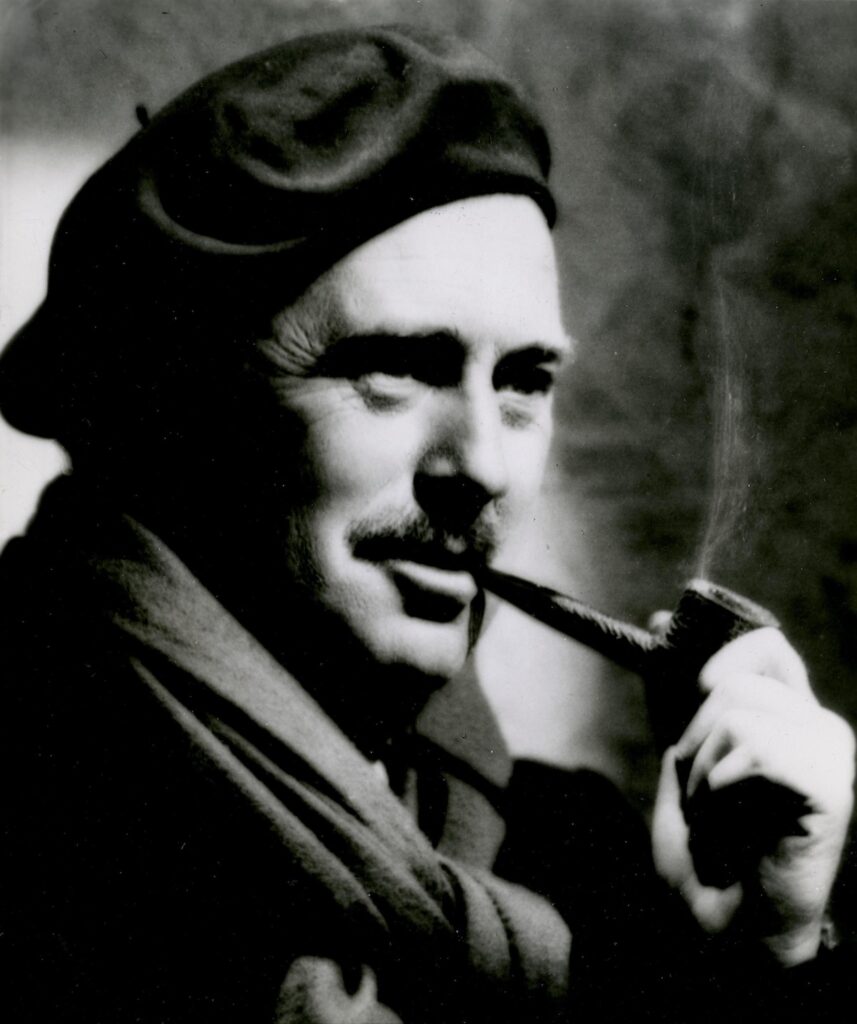

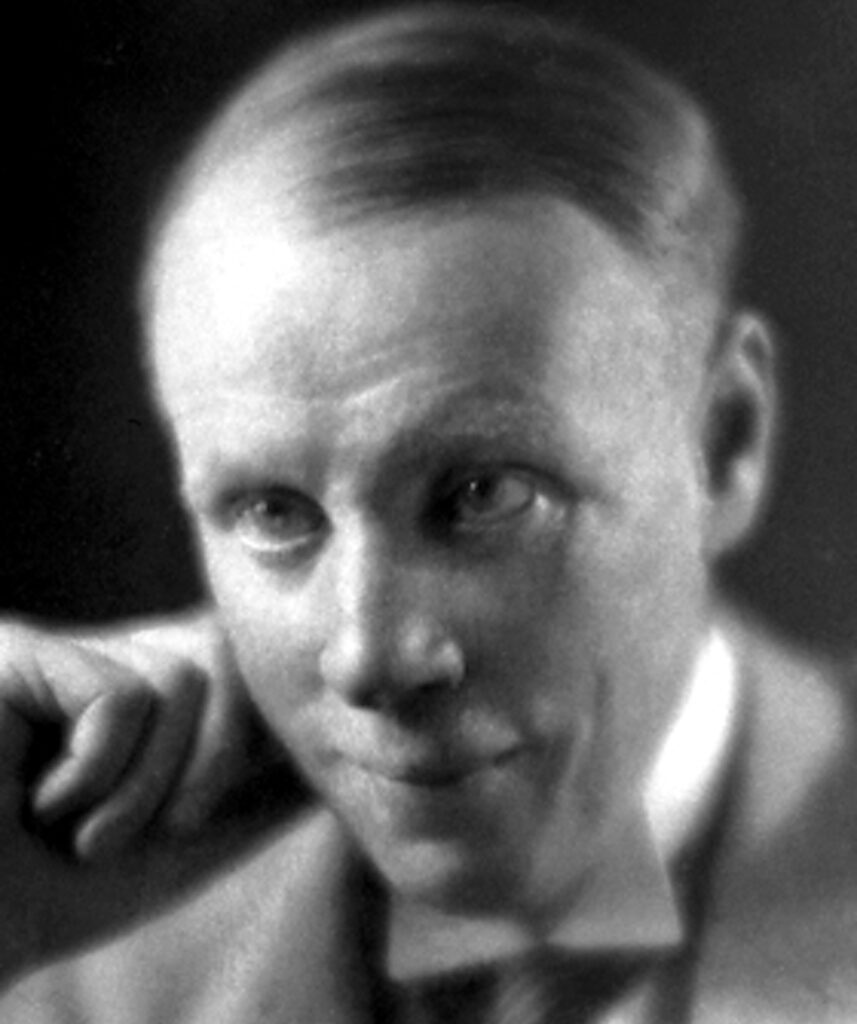

The book was written by novelist Sinclair Lewis (1885–1951), in collaboration with Paul de Kruif. De Kruif (rhymes with “life”) was a bacteriologist who conducted laboratory research at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York, a leading site for biomedical research in early 20th-century America. De Kruif was forced to resign in 1922, however, after penning a series of essays for Century Magazine accusing researchers—including his Rockefeller colleagues and superiors—of prioritizing profit over cures. The essays prompted his boss, Simon Flexner, to call for his resignation, and de Kruif transitioned to a full-time career as a science writer for popular audiences. He spent the next several months writing more articles against medical malpractice and quackery, traveling far and wide across the United States to interview experts.

One such expert was Morris Fishbein (1889–1976), physician and assistant editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, who also focused on exposing corrupt doctors. At around the same time, novelist Sinclair Lewis was interviewing Fishbein to gather information for a project of his own handling medical corruption. Anticipating that Lewis’s research would benefit from conversation with de Kruif, Fishbein introduced the two. Their meeting launched a multiyear partnership that involved travel to the Caribbean and Europe, heated arguments, tearful reunions, and, eventually, the snub that ended their relationship and muddled public knowledge of de Kruif’s role in the project.

Lewis was the author of bestselling novels Main Street (1920) and Babbitt (1922), but when he met de Kruif he had a new novel in the making: a story on the controversies and contradictions of U.S. medicine. Lewis was no stranger to this world, as many of his family members were doctors themselves, including his father, grandfather, brother, and uncle. Moreover, Fishbein had told him stories of profiteers selling fake cure-all pills and tonics, along with other forms of medical corruption. Lewis was also sensitive to some critics’ dislike of Main Street and Babbitt for being too satirical, and he now sought to write a story with a more likable protagonist while still criticizing corruption. De Kruif, an outcast bacteriologist and former med student, was intrigued. He’d been mulling over the idea of writing such a novel himself—at the suggestion of fellow bacteriologist and friend Karl Meyer (1884–1974)—but de Kruif wrote magazine exposés, not novels.

After an evening of visiting friends and heavy drinking in Chicago, de Kruif joined Lewis in his apartment to brainstorm. He told Lewis stories of his experiences as a young med student and then as a bacteriologist at the University of Michigan and Rockefeller Institute. In characteristic fashion, de Kruif didn’t shy away from emphasizing the hypocrisy of his former colleagues. Lewis, whose previous work centered heavily on calling out American moral inconsistencies, was eager to bring de Kruif on as a collaborator. Together—he hoped—they would write a bitterly accurate account of medicine in the United States.

It would be a few months before the collaboration truly got underway. In late 1922, de Kruif and Lewis reunited in New York to settle matters of business with Lewis’s publisher, Harcourt, Brace, and Company. In his memoir, de Kruif recalls Lewis’s pitch being quite different than their early plans back in Chicago:

The meeting with the publisher reeled Lewis back in, however, and de Kruif was satisfied that the projected novel could be a “work of art” after all. The three parties—publisher, Lewis, and de Kruif—then drew up their agreement. Although Lewis originally offered de Kruif half of all royalties, de Kruif requested only 25 percent. With Harcourt, Brace, and Company prepared to fund the duo’s research travels, they planned their departure.

Trouble was already brewing. Before they could even begin their journey, Lewis informed de Kruif of a change in plans: de Kruif’s name would no longer appear on the title page of the book. Lewis argued the book might not perform well if readers discovered the Sinclair Lewis had brought in someone else to help him write. De Kruif wrote that this explanation “sounded like what’s on the floors of stables,” but acquiesced.

The first stop for the writing duo, who set sail on the SS Guiana on January 4, 1923, was Barbados. De Kruif and Lewis explored the Virgin Islands, St. Lucia, Trinidad, Venezuela, Curaçao, and Panama, building the setting for their upcoming book. They developed a fictional island, St. Hubert, struck by the bubonic plague. The epidemic was inspired in part by contemporary interventions of U.S.-based researchers into tropical communities. For example, the Rockefeller Foundation Yellow Fever Commission began sending researchers in search of a cure to South American countries such as Ecuador and Columbia in 1916. They also drew inspiration from the 1900 plague outbreak in San Francisco.

As de Kruif and Lewis traveled, the people and places in the book began to take shape. De Kruif spent hours developing “fictional biographies” of certain characters, heavily inspired by his own mentors, peers, and coworkers. Indeed, the novel’s protagonist, Martin Arrowsmith, was meant to reflect Paul de Kruif, who pictured himself the embodiment of scientific “objectivity.” Like de Kruif, Arrowsmith clashes with doctors who prioritize profit over truth. He abandons his medical practice for a research post at a prestigious research institute, where he finds fault with his coworkers’ complacency.

After developing a possible cure for the bubonic plague, Arrowsmith travels to St. Hubert, where he plans to test his treatment on human subjects. Here, Arrowsmith must make an impossible choice: should he conduct a controlled experiment, likely sentencing the control group of infected patients to death? Or should he just administer the unproven treatment indiscriminately, compromising the experiment but possibly curing everyone?

This ethical dilemma captured one of the biggest debates of U.S. medicine in the 1920s, and it was personal to de Kruif. Previously, while he was still at Rockefeller, de Kruif was outraged that some researchers refused to use control groups. He argued this practice made it impossible to know if experimental treatments were combatting diseases as intended. (Much later in his career, de Kruif would change his tune, advocating for greater access to experimental treatments before their efficacy was proven).

In March, Lewis and de Kruif left the Caribbean for London. Traveling between England and France, their research now involved dining with bacteriologists such as William Bulloch (1868–1941) and Émile Roux (1853–1933), and touring laboratories. (These dinner meetings helped develop the structure of another project de Kruif was working on, the hit collective biography, Microbe Hunters.) While overseas, both Lewis and de Kruif documented their experiences collaborating with one another. Lewis wrote to his publisher that “[d]e Kruif is perfection,” praising the bacteriologist’s scientific knowledge, storytelling, and ability to stay out of Lewis’s hair. On many occasions, both men recorded their partnership as “perfect,” devoid of any rough patches. This, however, was not entirely the case.

In April 1923, while the pair was in London, de Kruif and his wife, Rhea, made Easter weekend plans with his mother and sister. Angered that they would not be joining him for Easter, Lewis fired de Kruif from Arrowsmith on the spot (and then, within a few hours, apologized and re-hired him). This episode, not representative of the general flow of the two-year collaboration, nevertheless reveals Lewis’s temperamental nature. Some tensions were also stirred up by de Kruif’s dislike of Lewis’s wife, Grace, fueled by his belief that she looked down on Rhea.

Lewis finished his draft of Arrowsmith from the comfort of Fontainebleu, France, in the absence of de Kruif. When they reunited in September 1923, Lewis presented the draft to de Kruif, who was thrilled.

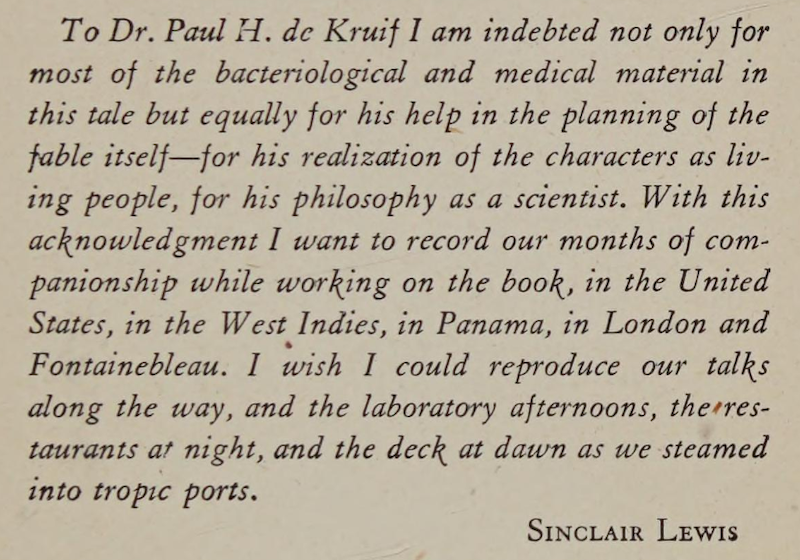

But when de Kruif saw the Arrowsmith page proofs in 1924, Lewis had acknowledged him merely for helping with the scientific details of the book. To de Kruif, the acknowledgement denied the hours of brainstorming, as well as his role in shaping the characters and the central themes of the book, especially its heart-wrenching conclusion. De Kruif angrily wrote to the publishers, telling them that if Lewis would not list de Kruif as collaborator, he should not acknowledge him at all. The publishers, in turn, informed Lewis. The limited preview edition of the book had only a brief note—“Paul de Kruif, assistant”—but after some back-and-forth between Lewis and de Kruif (mediated by Harcourt, Brace, and Company), the first trade edition of Arrowsmith contained a substantially expanded acknowledgment.

The disagreement over authorship and acknowledgement irreparably damaged the friendship. Henceforth, de Kruif ceased written correspondence with Lewis and avoided the author at all costs. In 1926, Arrowsmith won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Lewis, however, had previously determined that he would refuse the prize after his book, Main Street, was snubbed in 1921. Even without the Pulitzer Prize, Arrowsmith grew in popularity, making its way into classrooms and home libraries. Indeed, many of the scientists interviewed in the Science History Institute’s Oral History Collection mention Arrowsmith as a major inspiration for their own career trajectories. This project taught multiple generations of readers to strive for the qualities de Kruif and Lewis deemed most honorable in scientific researchers: commitment to the principles of controlled, meticulous study, a refusal to conform to the demands of authorities, and determination in the face of criticism and danger.

Unpacking the creative process behind Arrowsmith sheds some light on the difficult nature of collaboration on a project that was, for both Lewis and de Kruif, a meaningful adventure. Both had high hopes for the novel, believing it would propel them forward in their respective writing careers. Furthermore, both wanted to expose bad practice in American medicine as a matter of public necessity. With payment and personal pride at stake, however, de Kruif and Lewis seemed to alternate between smooth forward momentum and dysfunction, making their collaborative process just as memorable as the narrative they told through Arrowsmith.

De Kruif, Paul. The Sweeping Wind. Harcourt, Brace, & Co, 1962.

Gerald, James Fitz. “‘These Jests of God,’: Arrowsmith and Tropical Medicine’s Racial Ecology.” Literature and Medicine 39, no. 2 (2021) 249-272.

Gest, Howard. “Dr. Martin Arrowsmith: Scientist and Medical Hero.” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 35, no. 1 (1991): 116-124.

Greenberg, Stephen. “Microbe Hunters Revisited – Paul de Kruif and the Beginning of Popular Science Writing.” Houston History of Medicine Lectures. 7. 2020.

Kohler, Robert E. “A Policy for the Advancement of Science: The Rockefeller Foundation, 1924-29.” Minerva 16, no. 4 (1978). 480-515.

Lewis, Sinclair. Arrowsmith. Harcourt, Brace, and Company. 1925.

Löwy, Ilana. “Martin Arrowsmith’s clinical trial: scientific precision and heroic medicine.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 103, no. 11 (2010) 461-466.

Rosenberg, Charles E. “Martin Arrowsmith: The Scientist as Hero.” American Quarterly 15, no. 3 (1963): 447-458.

Schorer, Mark. Sinclair Lewis: An American Life. McGraw-Hill. 1961.

Stapleton, Darwin H. “Lessons of History? Anti-malaria strategies of the International Health Board and the Rockefeller Foundations from the 1920s to the era of DDT.”

Public Health Reports 119, no. 2 (2004). 206-215.

Tobin, James. “The Michigan Scientist Who Was Arrowsmith.” Michigan University: Heritage Project.

Verhave, Jan Peter. A Constant State of Emergency: Paul de Kruif: Microbe Hunter and Health Activist. Van Raalte Press, 2020.

Featured image: Detail of the cover of Arrowsmith.

Mapping Philadelphia’s industrial past with digital tools.

Memory, materials, and the history of science in the Eugene Garfield Papers.

Explore the history of science behind U.S. efforts to feed schoolchildren with Lunchtime exhibition curator Jesse Smith.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.