Touching the Past

The Institute’s museum education team partners with Philly Touch Tours to offer a more meaningful history of science experience.

The Institute’s museum education team partners with Philly Touch Tours to offer a more meaningful history of science experience.

Historic artifacts on display in the Science History Institute’s museum—whether they be an impressive mass spectrometer, a cuddly Teddy Ruxpin, or an everyday nylon stocking—serve as links to the past. These objects invite guests to learn about the people who once used them and the science they demonstrate.

Occasionally, when viewing collections items in our exhibitions, visitors are filled with such palpable impressions of the past they suddenly become overwhelmed with the need to touch. For me, one such object is the elegant blue nylon gown in our “Spinning the Elements” display.

When observing the dress, it takes all my strength not to reach out and brush my hand against its soft billowing skirt. In my imagination, I have worn this dress a million times, twirling and hopping to the gentle “oomp-pah-pah, oomp-pah-pah” of a graceful waltz. But it is only through my mind’s eye that I get to experience how this dress was loved and adored by its previous owner.

Alas, most museums are only designed to transport guests into the past through traditional viewing of museum objects, without touch or interaction. But visual learning can only go so far. If the goal is to rouse poignant and meaningful connections to history, touch becomes necessary.

Telling stories while interacting with historical artifacts allows guests to touch the lives of people who came before them—to feel what they felt, both literally and figuratively. And this is where the museum’s handling collection comes in . . . well, handy. Artifacts in this collection are meant to be interacted with by guests to facilitate learning. During our recurring Stories of Science program on Saturdays, museum educators bring out specific touchable objects to teach about various history of science topics, such as chemistry sets or elements and minerals.

Most recently, the museum education team has found another exciting use for our handling objects: touch-based programming designed to engage guests who are blind or have vision impairment. And for the past nine months, we have been working with the folks from the accessibility consulting organization Philly Touch Tours to develop such programming.

Philly Touch Tours (PTT) was founded in 2015 by Trish Maunder, an art and museum educator, to ensure that individuals with vision loss have equitable access to arts and cultural institutions. Having close personal ties to folks with vision loss, Trish has seen firsthand the ways in which museums can be unwelcoming spaces to the blind and low vision community, starting with the universal museum rule: “Do Not Touch!”

While the no touch rule is in place to safeguard the conservation of historical artifacts, it is also the biggest limiting factor for guests with vision loss to experience museum exhibitions. The PTT team also includes program director Katherine Allen and Vision Council members Simon Bonenfant and Denice Brown. This dedicated crew partners with Philadelphia institutions to teach staff how best to engage with blind and low vision visitors, and design touch-based tours that provide meaningful learning experiences.

“The ultimate goal is to have accessibility become embedded into an institution’s philosophy and to create sustainable relationships,” says Trish. She also shares that the process of designing inclusive programming turns into a very personal experience “because you are making human connections and sharing the desire we all have to want to know more and learn more and communicate more with whoever that audience is.” Katherine adds: “We want to inspire thinking and empathy and creativity around how to engage a community they [museums] may not have thought about before. To take away the reluctance to engage with the blind and low vision community. We are creating connections.”

To strengthen connections and safeguard positive impacts, it is vital to gain knowledge from folks who have vision loss. Simon and Denice instructed Institute staff how to best engage with guests who are blind. During these training sessions, Denice strives to impart comfort by “making sure the staff knows that using words like ‘watch’ or ‘see’ are normal words to say, and they shouldn’t be afraid to say them to us.” Because these folks are “your friend, they just happen to be blind . . . this is just a normal thing.” Simon adds that taking part in designing these touch tours is a privilege: “Witnessing the fruits of our labor, and the community building that happens, that is very rewarding.”

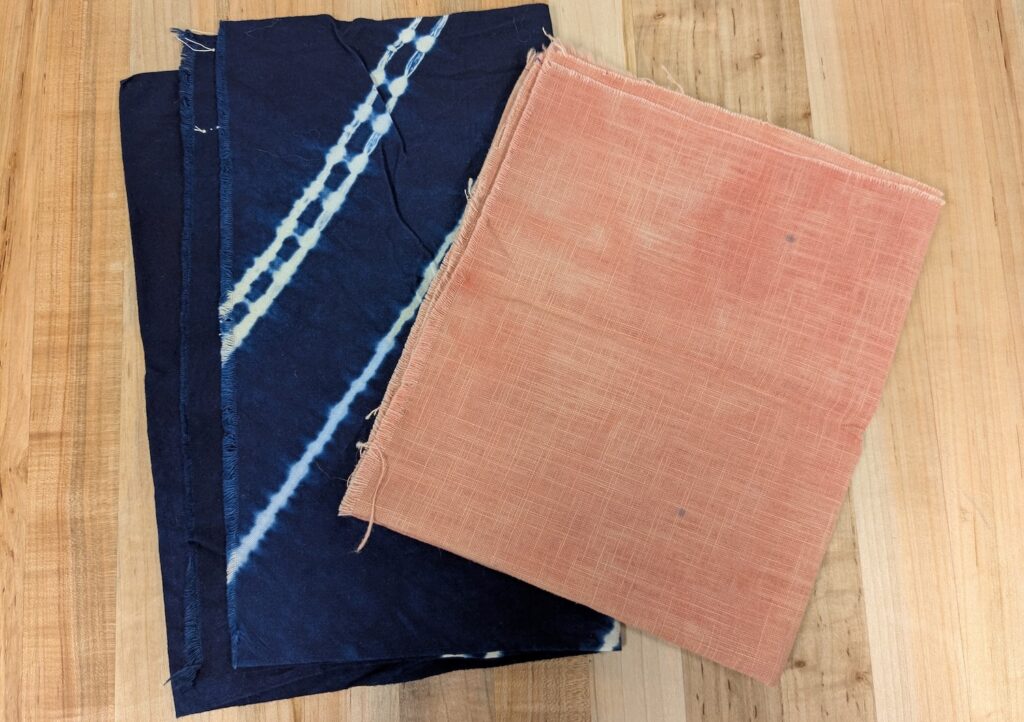

When the partnership with PTT began in June 2025, the first step taken in touch tour design was to determine which history of science topic might work best for a tactile learning experience. Coming off the heels of our popular BOLD exhibition, which covered the history of textile dyes, the handling collection had acquired a rich variety of fabrics and cloth samples. Likewise, displays in our permanent exhibition discuss the chemistry and development of many everyday materials, especially clothing. So, it became very apparent that telling the story of fabrics and fibers for our first touch tour would be the perfect fit.

Clockwise from top left: Indigo-dyed cotton cloth (left) and madder-dyed linen cloth (right); Arrow brand detachable cotton shirt collar, ca. 1920s; and detachable celluloid shirt cuffs, ca. early 1900s.

The idea of focusing on the history of science for a touch-based tour is very exciting to PTT team members, since science learning and the use of tactile tools go hand in hand. “Learning about science when I was in school, I had a lot of tactile aids, and I think that tactile exploration of science really makes a lot of sense,” says Simon. And some inspiring new tools have been developed to make science more accessible for the blind and low vision community.

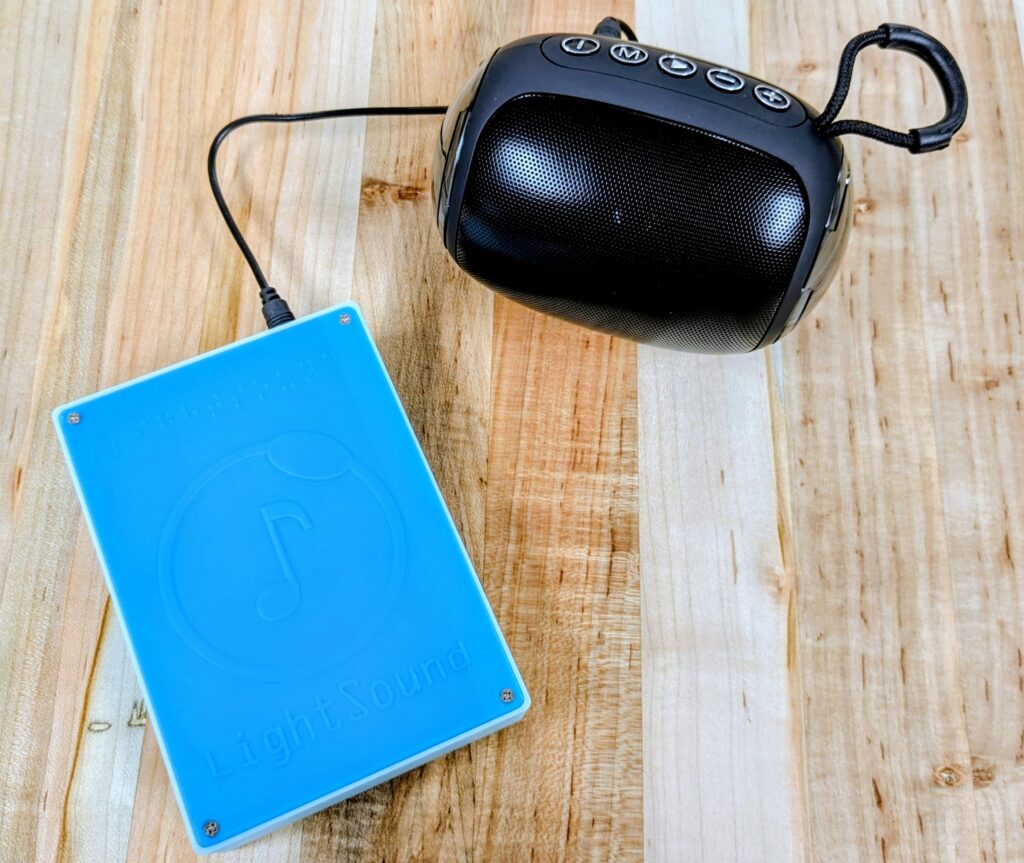

For example, the LightSound Project device was developed by astronomers in 2017 to be used as a tool to experience a solar eclipse with sound. The device converts light intensity to sound so changes in ambient light can be heard rather than seen. In 2024, PTT organized an eclipse watch event utilizing this tool, and Simon recalls being surprised by how much he was able to observe. “To simulate something that was visual, we ended up realizing there are a lot of sensory cues that you can get that are not visual. We would not have known that unless we took a chance and had this experience. And we realized something very profound, that [science] is more than just visuals.”

LightSound device and speaker.

Vision loss is no longer a disqualifier to participate in science. Denice shares that the organization Independence Science has developed “different measurement instruments to be used in the classroom for people who are blind to use their other senses to analyze data.” These tools ensure that science labs are “fully integrated” so all students may learn safely and independently.

The folks at PTT could not be more elated to witness these advancements. Katherine has observed that despite threats to diversity initiatives, “more institutions are now becoming more open to inclusion and the history of disability education. We are at another pivot point, and it is really exciting doing this stuff and working with each other. We are in this shift, and it’s pretty cool.”

The Institute’s museum education team strives to make everyone’s visit impactful, exciting, and fun. The purpose of our touch tour is no different. It provides an engaging experience for guests who are blind or visually impaired so together we may have meaningful conversations based on a stimulating sensory exploration of the history of science. Astronomer Allyson Bieryla said it best when speaking about the importance of science accessibility: “This is how we get the next great generation of ideas. Just because someone doesn’t have sight doesn’t mean they don’t have great ideas.”

And I think the world is ready for more great ideas.

It has been a privilege working with Philly Touch Tours, and we thank them for all the knowledge they so generously shared. Philly Touch Tours and the museum education team are very excited to share what we have created together!

For more information or to register for one of our “From Nature to Nylons: A Touch-Based History of Textiles” touch tours, please visit our events listing page.

Featured image: Blazing the Trail to New Frontiers Through Chemistry, detail of a page from a promotional booklet advertising products such as nylon stockings produced and sold by DuPont, 1940.

Mapping Philadelphia’s industrial past with digital tools.

Memory, materials, and the history of science in the Eugene Garfield Papers.

Explore the history of science behind U.S. efforts to feed schoolchildren with Lunchtime exhibition curator Jesse Smith.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.