The story of how abortion became legal in the United States isn’t as straightforward as many of us think. The common narrative is that feminist activism and the sexual liberation movement in the 1960s led to Roe v. Wade in 1973. But it turns out the path to Roe led over some unexpected and unsettling terrain and involves a complicated story winding through culture, society, disease, and our prejudices and fears about disability.

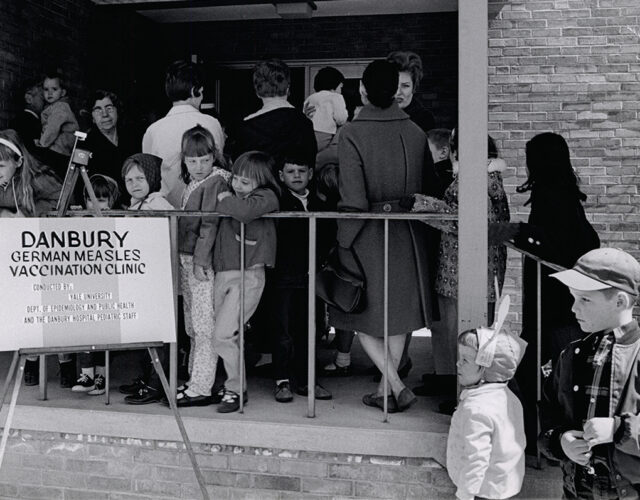

In the 1960s, a rubella epidemic swept the United States and panicked every pregnant woman in the country. Rubella, also called German measles, is a disease we hardly remember anymore, but it’s the “R” in the MMR vaccine. Though the virus is relatively harmless for most people, when contracted during pregnancy, it can severely harm the developing fetus. During the epidemic, many pregnant women who may have never identified as abortion-rights advocates suddenly found themselves seeking abortions and dismantling barriers to access.

Though not everyone agreed with these women, people listened. And this historical moment, sparked by a virus, helped pave the way for the legalization of abortion.

Credits

Hosts: Alexis Pedrick and Elisabeth Berry Drago

Reporter: Mariel Carr

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: James Morrison

Special thanks to our colleague Ashley Bowen for bringing our attention to this story and providing us with guidance along the way.

Physicians for Reproductive Health gave us permission to use the oral history interview with Jane Hodgson.

Music by Blue Dot Sessions: “Wahre,” “Kalsted,” “Gambrel,“ “Messy Ink,” “Throughput,” “Watercool Quiet,” “Uneasy,” “Drone Pine,” “Mute Steps,” “Thin Passage,” “Topslides,” “An Introduction to Beetles,” “Filing Away”

Resource List

Books and Articles

Drash, Wayne. “Mom at Center of ‘Wrongful Birth’ Debate: If Lawmakers Cared, They Would Have Called.” CNN. April 4, 2017.

Drash, Wayne. “Texas ‘Wrongful Birth’ Bill Fails to Pass.” CNN. June 7, 2017.

Dynak, H., T. A. Weitz, C. E. Joffe, F. H. Stewart, and A. Arons. “Honoring San Francisco’s Abortion Pioneers.” San Francisco: UCSF Center for Reproductive Health Research and Policy, 2003.

Hodgson, Jane E. “Oral History Interview with Jane Hodgson (electronic resource).” 2000. Physicians for Reproductive Health and Choice Oral History Project, Columbia Center for Oral History, Columbia University, New York.

Joffe, Carole. Doctors of Conscience. Boston: Beacon, 1996.

Loofbourow, Lili. “They Called Her ‘the Che Guevara of Abortion Reformers.’” Slate. December 4, 2018.

Reagan, Leslie. Dangerous Pregnancies. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

“Rashes to Research.” Exhibition Program, U.S. National Library of Medicine website.

Films

Cochran, Gloria G., and Winston E. Cochran. Challenge for Habilitation: The Child with Congenital Rubella Syndrome. 1977. Documentary. U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections website.

Fadiman, Dorothy. Motherhood by Choice, Not Chance. 2004. Documentary. Menlo Park, CA: Concentric Media.

Guttmacher, Alan F., Frank J. Ayd, and Richard D. Lamm. Indications for a Therapeutic Abortion. 1969. Documentary. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Public Health Service. U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections website.

Infections and Birth Defects: A Research Approach. 1966. Documentary. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections website.

Rubella Testing in the Small Hospital Laboratory. 1983. Documentary. Buffalo, NY: Mark-Maris, Inc. U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections website.

Sherri Finkbine Departs for Sweden. 1962. Huntley Film Archives. YouTube. Posted on December 4, 2015.

Society for Humane Abortion Press Conference. 1965. Newsfilm, KTVU, Oakland, CA. Bay Area Television Archive, San Francisco State University.

Transcript

Sherri Chessen: So I put the phone down and instead of crying like I’m kind of doing now, I put my hands on my hips and said I’m calling the county attorney’s office. And I called, and I said I just want to know what the attorney general has to do with interfering in any family’s decision to take care of their, what they think is best for their own family.

Dortha Biggs: It’s important that others understand what some of us did to get rights. And it scares me to think that people who have never walked in our shoes and have never experienced this try to make decisions for us.

Leslie Reagan: One thing you see is the insistence that as hard as it is, they are the ones who have to make the decision. The hard decisions are theirs to make.

Alexis: Hello and welcome to Distillations. I’m Alexis Pedrick.

Lisa: And I’m Lisa Berry Drago. Most of us think we know the story of how abortion became legal in this country. Activism in the 1960s led to Roe versus Wade in the 1970s, bing, bang, boom. It turns out the fight for reproductive freedom actually involves a complicated story around culture, society, disease, and our prejudices and fears about disability.

Alexis: In the end this is a story about hard choices and who should get to make them. Now we should say our story focuses on the women at the heart of the struggle, and disability is a big part of their stories. But the bigger fight for disability rights, the lived experiences of those with disabilities, is a much larger story that we can’t adequately cover in this episode.

Challenge for Habilitation archival film: Maternal viral infection during pregnancy, especially in the first three months, has the potential for producing a number of harmful effects in the developing fetus. An estimated 20,000 to 30,000 children were born with the congenital rubella syndrome as the result of the 1964–65 rubella epidemic in the United States.

Lisa: So imagine this. It’s the mid-1960s and you’re pregnant. There’s a rubella epidemic sweeping the country. It’s very contagious. Rubella is, in a way, kind of like Zika. It’s pretty harmless for most people, even for most children, but when it’s contracted during pregnancy, it can cause devastating birth defects in developing fetuses. This is a news clip from 1969.

NBC News Archive: Crippling abnormalities, bad sight and hearing, heart disease, mental retardation. At least 20,000 other babies were stillborn. Rubella epidemics come in cycles six to nine years apart. Most authorities expect the next epidemic to come in the spring of 1971.

Alexis: Rubella is one of those diseases that we barely remember anymore, but you’re probably familiar with the vaccine. It’s the R in the MMR vaccine. But in 1964 there’s no vaccine yet and no reliable diagnostic test yet either. Doctors are still working on that. There’s also no real way to prevent yourself from getting it. And if you wind up having a baby with congenital rubella syndrome, you’re on your own. There’s no social support of any kind for people with disabilities.

Lisa: And abortion is not legal, and it won’t be for nearly a decade. Dortha Biggs was one of the tens of thousands of women who contracted rubella while pregnant in the 1960s. It wasn’t during the big epidemic of 1964 to 1965 but years later in 1969. She had it when she was just two-and-a-half weeks pregnant, but it went undiagnosed. So it wasn’t until after her daughter Leslie was born that she realized something was wrong.

Dortha Biggs: I was walking down the hall, and the way the lights hit Leslie’s eyes … I thought, something doesn’t look right about her eyes.

Alexis: Cataracts are a frequent symptom of congenital rubella syndrome. Blindness often follows like it did with Leslie.

Dortha Biggs: I think one of the most difficult things for us was that we just kept getting blow after blow after blow because one disability would show up and then other ones would show up and then another one would show up.

Lisa: Children born with congenital rubella syndrome like Leslie often have multiple disabilities, and the virus’s effects on the fetus are more severe the earlier the mother has it. Remember, Dortha had it when she was just two-and-a-half weeks pregnant. Leslie is now 50 years old. She’s blind and deaf. She has heart problems and severe intellectual disabilities.

CNN Clip: Can Leslie hear you? No. Can Leslie see you? No, no. How do you communicate with your daughter? This is the way: it’s through touch. Not hearing or seeing, I’ve often thought, you know, this is just a dark silent world for her.

Lisa: Dortha struggles with the idea that things could have gone differently.

Dortha Biggs: I had been ill before I even knew I was pregnant and went to the doctor to see, you know, what was going on. And I had had a slight rash. So I asked the doctor, could this rash be rubella?

He first said, well, if you were going to have rubella, you’d have had it in the 1964–65 epidemic. He did tell me that he ran a test and that it was not rubella. So when Leslie was born and we started seeing disabilities, I went back to him, and he said, well, I’m just going to have to be more careful next time. He said, I was so sure that it wasn’t, I didn’t run the test.

It’s been a suffering life as I see it, and it’s something that I wish I could have really known at the early part of the pregnancy because I would never have let her go through all this. I definitely would have chosen abortion to save her from all she’s gone through.

I think it’s important for people to know that it’s not because you think, oh, I’m going to have a baby who’s disabled and it’s going to cause me a lot of trouble. It’s more that you just don’t want them to have to go through that. It’s not you’re not wanting you to go through it. You don’t want the child to go through it.

Alexis: Maybe you’re wondering what Dortha Biggs means when she said she would’ve gotten an abortion in 1969, because we just told you abortion was illegal. Well, there’s an asterisk.

Lisa: A big asterisk, so big, in fact, that this entire story actually takes place within it. Roe versus Wade won’t happen until 1973. But before then abortion laws in most states had some kind of exemption for medically necessary or so-called therapeutic abortions, but each state made up its own rules. Some are strict. In Arizona or Minnesota, for example, you could only get an abortion if you were going to die. Other states’ rules were more vague. In Illinois, for example, there just had to be a bona fide medical reason.

Alexis: But even in states where therapeutic abortion was legal and the grounds for one were well-defined, getting one was anything but straightforward. It varied between states but also between cities, hospitals, individual doctors.

Lisa: By the mid-1960s there was already a growing movement of feminists who were pushing to legalize abortion without restriction. But they weren’t gaining enough traction. To get to Roe it actually took an epidemic and an uneasy alliance with an unlikely group of activists—1960s housewives.

Alexis: During the rubella epidemic, many women who may have never identified as abortion rights advocates found themselves seeking abortions, only to discover that that asterisk was not big enough. So they pushed on it. Many of them spoke out and insisted that they were in an impossible position, one that was not only devastating and heartbreaking but completely out of their control. And they demanded that they get to be the ones to make tough decisions about their own reproductive lives. They demanded that people listen to them, and people did—eventually.

Lisa: Because of who these women were, but more importantly how they were portrayed by the media—white, middle-class, responsible, married mothers—they changed the national conversation around abortion from something rooted in sexual depravity and danger to something rooted in the cares and concerns of motherhood.

Alexis: Though certainly not everyone agreed with them. People listened, and this historical moment, all sparked by a virus, paved the way for the legalization of abortion.

Chapter One: The Origin Story

Alexis: Rubella has been around for a long time. It’s not like it suddenly appeared in 1964, but for most of its history, no one was really worried about it.

Leslie Reagan: You know, it’s an infectious disease. It was very minor. And there are lots of things that people got that we don’t get so much anymore in the U.S.—mumps, chickenpox, scarlet fever in the early 20th century—that were dangerous, and you would quarantine your kids at home and you hope they survived. But German measles was a really, really minor rash that lasted a couple days. You didn’t even try to confine your kids to bed, and nobody worried about it. Sometimes you didn’t even know you had it.

Lisa: Historian of medicine Leslie Reagan wrote a book about the rubella epidemic and how it helped change abortion law, called Dangerous Pregnancies. And by the way, she calls rubella German measles when she’s talking about the 1960s because that’s what most people would have called it at the time.

Leslie Reagan: So this wasn’t something people paid any attention to, and it’s not until World War II that there is a connection that’s figured out between German measles, pregnancy, and a series of birth defects.

Alexis: Remember how Dortha Biggs said it was Leslie’s eyes that caught her attention? Cataracts were also the key clue for an Australian ophthalmologist named Norman Gregg in 1941. All of these mothers whose babies had cataracts started coming to see him.

Leslie Reagan: Now this is a very rare problem, and he begins to investigate this and go and send out questionnaires to other doctors to find out, are you seeing many of these cases? And then when he begins to make a connection, they also start talking to the mothers of the children who are bringing them in. And somebody said to him, you know, I wonder if it’s related to my having German measles when I was pregnant. And rather than dismissing it as, that doesn’t make any sense, that’s ridiculous, he actually kept that as a question in mind and began looking at the other cases and asking, Do you remember whether you had a rash? Did you have German measles? And he found out that in almost all of the cases where they could get information, they had had a rash; they had had German measles during their pregnancy.

Lisa: Norman Gregg did something fairly radical. He listened to women, and he learned something important and alarming from them. A virus that had previously been thought of as harmless was in fact harming babies in utero. And remember, this is 1941. Women won’t be told about the dangers of things like smoking and drinking during pregnancy for another few decades. Most people don’t yet understand that things that a pregnant woman ingests or a virus she contracts can affect a developing fetus. In 1941 Norman Gregg didn’t have the whole picture yet, but he started spreading the word. He talked to other doctors at medical conferences. He also went on the radio to alert regular Australians.

Leslie Reagan: And he immediately got phone calls from other mothers where their children were maybe three, four, five years old. And they said, my child is deaf and I had German measles during pregnancy. So I think there’s something else as well, and then because of those calls, he followed that. So that’s one of the things that’s really important in this, is he listened to the mothers when they came in with their knowledge of their infants and their own bodies and their suspicions.

Alexis: Newsweek and Time wrote about Gregg’s discovery in 1944 and 1945, and in 1949 studies from around the world confirmed the harmful effects of rubella on developing fetuses.

Lisa: But throughout the 1950s and into the early 1960s, medical advice columns and newspapers and even public health pamphlets intended for pregnant women were silent about it. Leslie Reagan says that this misguided, paternalistic approach was actually intended to reassure women by keeping information away from them.

Alexis: But when the rubella epidemic hit the U.S. in 1964, newspapers finally started sounding the alarm, and women were caught off guard, partly because expectations about pregnancy and child mortality had changed.

Leslie Reagan: This particular moment is the middle of the baby boom. And we now have women having three, four, five children, and they have them all close together. So everybody’s having babies. They don’t expect to die in childbirth, and they don’t expect that their children, that their infants, are going to die either. They expect healthy babies.

Alexis: So the idea of a rubella syndrome was frightening and contrary to people’s expectations, and women didn’t have a lot of information.

Lisa: At the same time, the news did sound eerily similar to something that had just happened in Europe.

Chapter Two: Thalidomide and Disability

NBC News Archive: Thalidomide is a sedative once given to pregnant women, until it was discovered that they frequently, after receiving it, gave birth to deformed children. Thalidomide is now banned everywhere, but the ban came after an epidemic of thalidomide babies in Germany and in Britain.

Lisa: In 1962 the U.S. watched from a distance as the so-called thalidomide disaster hit Europe. The drug was thought to be so harmless it was given to women for morning sickness. Of course, later we realized it wasn’t harmless at all.

Alexis: There were a whole range of disabilities associated with thalidomide, but the FDA never approved it. So people in the U.S. saw themselves as having avoided a tragedy.

Lisa: Which reminds us of the undercurrent running through this entire story, a deep-seated fear of disability.

Alexis: When housewives began demanding abortions, it wasn’t just that mainstream society saw them as nice, respectable ladies who of course should make decisions about their own bodies for themselves. It’s that each one was seeking an abortion for a very specific reason: to prevent what mainstream society saw as a tragedy—a disabled child. Thalidomide sparked the anxiety among women, but rubella made it persist.

Leslie Reagan: And so to understand the world they’re living in, this is what they’re being told. There are these headlines: there’s going to be 20,000 damaged babies in the United States with German measles, and they’re calling them deformed and dangerous children that are going to be born. So the picture that people had in their minds and the pictures that were running in the newspapers at the exact same moment were pictures of thalidomide babies, as they were called, and they were called freaks and monsters. This was the picture in people’s minds, and they were terrified.

Alexis: The response to the forecast of so-called damaged rubella babies was widespread panic, and it was considered a crisis in the making. But a huge part of that crisis was actually the social situation that these children would land in.

Lisa: Beyond the stigma around disability, which let’s face it, still very much exists to this day, in the 1960s there was zero material social support for babies, children, or adults with disabilities.

Leslie Reagan: They don’t think at all about what can we do for the babies. How could we improve the world for them? It doesn’t come up as a question. Everything that might be needed was on the shoulders privately of the parents in terms of education, in terms of therapy, medical needs. There’s no right to public education. There’s no mainstreaming. There’s not like a disability rights movement. This is all in the future.

Lisa: In fact, many parents of children with congenital rubella syndrome went on to advocate for disability rights and helped eventually get the Americans with Disabilities Act passed. Of course, that’s still decades away, but it was this historical moment when the specter of thalidomide enters the American consciousness that abortion too enters the debate.

Alexis: In 1961 Sherri Chessen was living in Arizona with her husband and four young children. She was pregnant with her fifth when she took some thalidomide her husband had gotten in Europe.

Sherri Chessen: I can still remember him putting them up in the highest cabinet in our kitchen. Why he was saving them, I have no idea. I never thought of that till this moment. Why did he save them?

Lisa: Sherri Chessen, by the way, is called Sherri Finkbine in almost all the media we found of her. She told us that Finkbine was her first husband’s name, but it was never her legal name. So in a sense, she says, the press created Sherri Finkbine.

Alexis: Sherri became the first woman in the country to deliberately tell the public about her decision to get an abortion, but that was not her original plan. She quietly went to her doctor in Arizona, and he consented to a therapeutic abortion. But before the scheduled procedure, she started to worry about all the other women who might find themselves in the same position.

Sherri Chessen: My first thought was, oh my God, the Air National Guard from Phoenix had been in Germany the year before. So I thought maybe they brought it back and other mothers would inadvertently take it like I did.

Alexis: So she called the newspaper and anonymously told a reporter her story.

Sherri Chessen: That Monday on the front page of the paper was an article with the words, “Baby-deforming drug may cost a woman her child here.” It did not name me at that time. It came close. It said “Scottsdale mother of four,” and I think it said that Bob was a teacher at Scottsdale High School.

Lisa: It didn’t matter what was printed. The county attorney announced that any doctor who gave her an abortion would be violating Arizona’s abortion law, which, remember, only permitted them if the woman was going to die. Sherri’s doctor called her at work and told her he couldn’t go through with it.

Sherri Chessen: So I put the phone down, and instead of crying like I’m kind of doing now, I put my hands on my hips and said I’m calling the county attorney’s office. And I called, and I said, I just want to know what the attorney general has to do with interfering in any family’s decision to take care of what they think is best for their own family.

Lisa: Sherri did get an abortion, but she had to go to Sweden to do it. Every doctor she approached in the U.S. refused her for fear of being prosecuted. Her story became a sensation, and reporters documented every step of her experience. Here’s a news clip from 1962 just as she’s leaving for Sweden.

Sherri Finkbine Departs for Sweden, archival film: What are your plans after Sweden? I’m so worried about today and that I just want to do what’s right for myself and my family. And I don’t feel bitter towards anyone. I don’t feel bitter towards people who oppose us religiously. I only hope that they know, can feel that we’re doing what’s best in our case and could feel some of what’s in my heart and trying to prevent a tragedy from happening.

Alexis: As American women watched her story unfold, they learned two things. One was how dangerous thalidomide was. The second was how hard it was to get an abortion for what people increasingly saw as a valid reason.

Lisa: And even though she was an unlikely spokesperson for abortion, she was also kind of the perfect one to change the conversation. In 1961 the media framed abortion as dangerous and women who got them as sexual deviants or at best victims. Then along came Sherri. She was young, married, white, and a mother four times over. She was also pretty and practically made for TV. In fact she was actually the beloved host of a children’s TV show called the Romper Room.

Alexis: She was completely inoffensive to 1960s middle America, and she went on TV and very sweetly told the world that she needed an abortion. And she explained why, and they listened to her.

Society for Human Abortion Press Conference, archival film: This is Sherri Finkbine, who was at the center of the 1962 thalidomide controversy, who was also at today’s press conference.

Sherri Chessen: Let me tell you first. I am not an expert in this field. I have never studied the question. I’m not a doctor or a lawyer. I’m not sociologically involved at all. All I know is that I was somebody who needed one under certain given conditions.

Lisa: A Gallup poll showed that 52% of Americans approved of her abortion, but there were so many people who didn’t approve, to put it mildly, that the FBI had to help protect her family.

Sherri Chessen: The negative reaction was pretty damn ugly, I will tell you, in some of these letters. They would send me a picture of myself with a dagger through my head, with blood running down. The worst ones were pictures that people would send cutting the limbs off of my children, and, you know, it was heartless. It was criminal. It was insane.

Alexis: We asked Sherri if she was surprised that she had to leave the country to get an abortion.

Sherri Chessen: I guess shocked would be more than surprised because I thought my doctor would just pop me in the hospital. I realized one day I had poisoned myself with a man-made poison, and I was going to get a man-made doctor to get that poison out from me. And I just fought till I was successful. But the trouble is pregnancies don’t wait while you’re fighting. I was lucky I found this out when I was, you know, just a couple months pregnant. So I had a little more time because I always felt if I felt quickening, you know, the baby move, I was really gone because then it would become, instead of fetal growth as I was told to think of it, it would become a baby. And I didn’t want it to be a baby.

How does a mother knowingly bring into the world a child to suffer? I cannot do it. I couldn’t do it for two seconds. Knowing what I knew, I had to take the course that I did, and I don’t regret it.

Chapter Three: The Mothers

Alexis: As the rubella epidemic unfolded, the realities of caring for babies and then children with multiple disabilities became concrete.

Challenge for Habilitation, archival film: This group of one-and-a-half to four-year-old children in the clinic reception area are all in the rubella program at the Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

Individual sessions with the social worker focus on current stresses produced by the presence of a handicapped child in the family.

Lisa: Dortha Biggs already had a young son when her daughter Leslie was born.

Dortha Biggs: She was in the hospital about six months her first year of life. Within the first just few years, she did have a total of 20 surgeries. We did everything in the world we knew to do to try to give her the best chance we could. We were so poor. We didn’t have, we had just borrowed money to, you know, to do anything that we could. One of the hardest lessons that kind of hit me was when she became school age. I worked for the schools. I worked for the Dallas public schools. And I went into the office, and I said, you know, I want, I know that you don’t have a facility to help her, but I want her enrolled. She’s of age to be enrolled in school, and I want her name down so that you know that she is out here. And they refused to even do that.

Lisa: Dortha’s husband left the family when Leslie was five.

Dortha Biggs: I think his words were, I just don’t know how to handle it.

Alexis: And so Dortha was a single mother to both Leslie and her son until Leslie was nine and she went to live in a group program for children with congenital rubella syndrome.

Dortha Biggs: If I don’t sound at this point being sorry for myself or dramatic here, which I’m trying not to do, but it was literally 9 years of, you didn’t know if you could take a shower. You couldn’t do anything because you had to be on alert all the time and, you know, be able to provide that care. And it was, I guess I went into probably deep depression during those times.

I don’t think I recognized it then, but I know that I can remember thinking, you know, oh, if I had never been born, then this wouldn’t have happened to her.

Lisa: Some people were starting to recognize the impossibility of the situation. And it wasn’t only about how 1960s America viewed and treated disability; it was also how they viewed and treated women.

Alexis: The gender imbalance was real, and the unequal demands on women began during pregnancy, starting with an impossible assignment. Just don’t get rubella.

Leslie Reagan: So German measles, what are you supposed to do when you get this message? Here’s an epidemic. The main vector is little kids. And then the advice that they’re given is, okay, so avoid children. Women of childbearing age avoid children. So this is the most ridiculous advice. It’s the baby boom. It’s not exactly easy for women to avoid children. Their lives are often wrapped up in children.

Alexis: We probably don’t have to tell you that when these women brought their babies home, they were the primary caregivers.

Lisa: Because of the lack of societal support, because of how hard that made it to keep special-needs children at home and how expensive it could be, many parents saw no other option but to place their children in institutions. In fact, doctors often pressured parents to institutionalize their children at birth.

Leslie Reagan: Newborn infants are institutionalized commonly at that time. They’re advised to institutionalize the blind child, the intellectually impaired child. Just go have another baby.

Alexis: In some ways, these women were losing their children no matter what.

Lisa: If this all sounds like a trap, that’s because it was. There was no ideal or perfect choice here. That’s what we mean when we keep saying this was an impossible situation. Women recognized that.

Leslie Reagan: And you have right away women looking for abortions. Right off the bat. I mean, they put it all together themselves, and they find people and they say, you know, I’m pretty sure I’ve been exposed. I want an abortion.

Alexis: It’s important to note that throughout the roughly 150 years between the first law criminalizing abortion in 1821 and Roe v. Wade in 1973, women still had abortions. A lot of them.

Lisa: They just had them quietly and very often unsafely. Estimates of how many women died from illegal abortions in the pre-Roe era range from 1,000 to 10,000 each year. Rubella was not the first time women got abortions, and it wasn’t the first time they’d talked about it either.

Leslie Reagan: But it was talked about privately, in kitchens, in friendships, but not in public forums. In the media and in newspapers, the representations of abortions were always about death and crime and sexual deviance. So it’s not until first, thalidomide with Sherri Finkbine, and then German measles that you have women who have abortions themselves talking about why, and why they need to, and really being kind of listened to seriously really for the first time. One thing you see with the women speaking is the insistence that as hard as it is, they are the ones who have to make the decisions. The hard decisions are theirs to make.

Lisa: Media attention was key. in 1965 Life magazine devoted a cover story to rubella and abortion. Inside was a photograph that took up two full pages. It showed women in hospital beds waiting to get abortions because of rubella.

Alexis: The title of the article was “The Agony of Mothers about Their Unborn.” These women were always talked about as mothers, and this brought them a lot of sympathy. They weren’t shirking their maternal duties. They wanted to be mothers. Many of them already were.

Lisa: People worried about how their family lives would be disrupted, how other children might suffer. In one interview, Sherri Chessen actually told the media that without an abortion, she felt she would only be able to be a partial mother to her other children.

Alexis: So this is kind of the twist. Yes, a movement to legalize abortion is gaining steam, and yes, people are starting to listen to the women, but in some ways it’s for the wrong reasons.

Leslie Reagan: It’s not what most of us think of as the movement for abortion rights because it’s not grounded in sexual freedom.It’s really about family and children, and it’s grounded in motherhood.

Alexis: Rubella mothers weren’t talking about abortion in terms of sexual liberation, but in the 1960s there were other women who were. One of them was Patricia McGinnis, widely considered the first abortion rights activist in the country.

Lisa: If Sherri Chessen was the gentle wave of the abortion rights movement, calmly convincing the world that things needed to change, Pat McGinnis was the fire. She advocated for total repeal of all abortion laws. She helped connect women to illegal abortion providers or ones out of the country. She also taught them how to do it themselves.

Alexis: Pat McGinnis never asked women why they needed abortions. She just trusted that each one had her own good reason.

Motherhood by Choice, Not Chance documentary film clip: Do you approve of abortions for any reason? Some hundred thousand women every year, this is California women alone, subject themselves to improperly or illegal abortion. I think that in itself is a rather staggering figure, and I feel great indignation as a woman to think that women have to subject themselves to second-rate medical care for a safe surgical procedure.

Alexis: But women like Pat McGinnis weren’t gaining traction with mainstream America. It took women talking as mothers, about disability, for the idea of abortion rights to gain traction.

Leslie Reagan: I think a lot of feminists, lots of us, did not want to look at what this meant—that German measles was about birth defects and disabilities, that this was a scary thing to touch. But that’s what they begin talking about, that it’s as mothers they make this decision. And eventually they do change the laws.

Chapter Four: The Doctors

Lisa: By the late 1960s most doctors had come to agree that rubella was a valid medical reason for an abortion. In fact, many doctors had already been providing abortions for other reasons often out of a sense of ethical obligation. An outrageous number of women died from illegal or so-called back-alley abortions for what could have been a safe surgical procedure. Doctors saw the results in their emergency rooms.

Lisa: Jane Hodgson was an obstetrician in Minnesota during the 1960s. Minnesota’s abortion laws were very strict, and Jane became frustrated by not being able to help the women who came to her desperate for abortions. Jane Hodgson died in 2006. The following are excerpts from an oral history that Columbia University did with her in 2000.

Jane Hodgson: I was besieged by women who wanted pregnancies interrupted. I would warn them about illegal abortion. I could do nothing about it. But you know very well that some of them were going to ignore you and they’d be back. And then sure enough, they’d be back in my office in a few days, and they’d be bleeding and I would have to take care of them.

Alexis: Sociologist Carole Joffe writes about doctors like Hodgson in her book Doctors of Conscience.

Carole Joffe: I mean she would refuse women, and then she would tremble looking at the local paper. She would tremble, you know, to find out if they killed themselves.

Jane Hodgson: One of the first patients that I saw there was a young woman who had gone through a series of pelvic infections, I’m sure following an abortion. It was a tragedy. We all knew that this young woman was going to die eventually because she was just getting worse and worse and worse.

You think now I could have prevented this. She came to me when she was well, and if I could have solved this problem for her, she would have been spared all this. When people asked me if I was ever worried about the abortions that I had done, I said, no, the only ones that ever haunt me are the ones I didn’t do. I said, and was quoted as saying, this was lousy medicine that we were practicing by not taking care of these women.

Carole Joffe: She said, you know, I had been taught abortion was immoral, and at a certain point I realized the law is immoral.

Lisa: In Minnesota the law was clear. Abortion was forbidden unless the woman was going to die. But in other states the laws were not so clear. And this put doctors in tricky positions.

Carole Joffe: Doctors were operating in a gray area. I mean, they just didn’t know whether some of the abortions they were doing were legal or not legal. In the pre-Roe era, if a woman came to a doctor and said, I don’t want to be pregnant anymore, and was otherwise healthy, which describes most of abortion patients, and they did an abortion on her, they knew they were doing something illegal. When a woman was very sick like with rubella, it just wasn’t clear. So it was a very high-anxiety time.

Alexis: In the late 19th century, when abortions were first criminalized, the system for approving them in hospitals was actually very informal.

Carole Joffe: Three guys, and they were always disproportionately guys, you know, would get together. One would say, look, I have this patient, and the other two would say, okay, you can do it. Over time it became more formalized. They started what’s known as therapeutic abortion committees. These committees were in the words of one doctor a complete and total disaster. I mean, it was very clear how unfair they were. There was a quota. You couldn’t do too many or you would invite unwanted attention.

Lisa: The committees caused problems for doctors, but they caused more problems for patients.

Leslie Reagan: It was a harrowing process. Their first doctor would have to agree to it or suggest it, and then they would have paperwork to complete, and they might have to go through interviews with additional physicians. They might go through additional medical exams, meaning gynecological exams, and the review board could accept or reject this original recommendation for a therapeutic abortion. And then if she’s rejected, she might try another hospital. But if they go backwards to try to find out why did the other hospital, what was their decision? It’s basically a blacklist because they listen to each other.

Carole Joffe: It was more likely to be private patients than so-called ward patients—in other words, the patients who came to the clinics but didn’t have a private doctor. I mean it was like everything else in American society—stratified by class and race.

Lisa: Anxiety was in the air for doctors, and it soon came to a breaking point. In 1966 the California Board of Medical Examiners charged nine prominent doctors for performing abortions on women who had had rubella. These were considered the most legitimate kind of abortion. Each one had gone through the therapeutic abortion committee process. Until this point the risk to doctors had mostly been theoretical. Prosecutors just didn’t actually investigate abortions that took place in hospitals. They spent their energy on the blatantly illegal back-alley ones.

Alexis: Leslie said that this went against our historical understanding that the law didn’t bother “respectable” medical men. It challenged the understanding that what goes on between doctors and their patients was private. The investigation of the San Francisco Nine, as they were called, energized both the growing antiabortion movement and the growing abortion rights movement. It turned doctors into activists.

Lisa: By 1967 a nationwide survey reported that 93% of doctors supported abortion reform, and like the women who started publicly admitting to needing abortions, doctors started announcing that they performed them. They realized that in order to practice the kind of medicine they wanted to practice and the kind their patients wanted them to practice, the laws had to change.

Alexis: Throughout the 1960s things were changing fast, but then in 1968 a medical discovery almost derailed the energy of the abortion activists.

NBC News Archive: The National Institutes of Health today disclosed development of a German measles vaccine, which in tests so far has proved more than 90 percent effective in preventing the disease. Officials say it’s possible the vaccine could be on the market within the year.

Rubella Vaccine archival film: Now with an approved vaccine, prospects are good that the birth defects of rubella can be eliminated. It depends on the medical profession and the parents of America.

Leslie Reagan: Doctors from the very beginning immediately were like, we need a vaccine. And it was always this imagined, you know, beautiful future where the vaccine solves everything. Not just we won’t have German measles anymore, but that we will not have the problem of therapeutic abortion, and we won’t have to deal with the moral question or the legal question, the social question, for women of how do you decide what to do when you’re in the middle of this? And we’ll just eliminate that problem. Which of course also doesn’t eliminate it. It’s one particular event. It’s just the case of German measles. It does not eliminate this at all.

Alexis: On the surface the vaccine was a simple scientific solution to the simple scientific problem of rubella. But the situation was actually very complicated, and women realized there was no simple scientific solution. They needed a cultural one, a shift that would let them make complicated decisions for themselves.

Lisa: By the time the vaccine was made available, the tide had changed. The abortion genie was out of the bottle, and it wasn’t going back in. Even the initial narrow arguments for therapeutic abortions, it was no longer enough. Even Sherri Chessen kept moving forward towards total repeal when she started to realize how her original position had been too limited.

Sherri Chessen: You know, if it isn’t thalidomide, if it isn’t rubella, it’s going to be something else.

Leslie Reagan: Within a year they’ve got all these different organizations, and they’re right away saying, this will not be enough because we know all the other reasons that women need abortions. But they’re in a political world that started out really small, where reform was first brought up by doctors and lawyers in order to protect doctors. That’s where these laws first came from. And the only reason they went anywhere was because of German measles and the demand from women across the country and the anxiety. And these laws got pushed forward, and then you have actually, you know, people calling for repeal. It’s really only a few years later. It’s really pretty fast.

Alexis: By 1970, 12 states had passed reform laws, and that year New York, Hawaii, Alaska, and Washington repealed their criminal abortion laws completely.

Lisa: Something else happened in 1970. A woman in Texas named Norma McCorvey filed a lawsuit against a district attorney named Henry Wade. She was single, pregnant with her third child, and had tried to get an abortion. But her life was not considered in danger, so it was illegal in Texas. And she couldn’t afford to leave the state. Her case made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where they used the pseudonym Jane Roe. This was Roe versus Wade.

Roe v Wade Archive: The Supreme Court today ruled that abortion is completely a private matter to be decided by mother and doctor. The seven-to-two ruling to that effect will probably result in a drastic overhaul of state laws on abortion. Specifically, the court today overturned laws in Texas and Georgia and ruled the government has no right to enter into a decision which should be made by the mother and her doctor.

Alexis: The 1973 ruling put an end to the therapeutic abortion puzzle. It was a huge win for all the women who fought to make it happen, from Pat McGinnis to Sherri Chessen, and also the doctors, because without them fighting to protect themselves, it might not have happened at all.

Carole Joffe: The main author of Roe was Harry Blackmun, who did a great service to American women. And I in no way mean to at all to denigrate him, but for him, writing Roe was all about protecting doctors. It’s not that he was unsympathetic to women getting abortions. But you know, if you read the language of Roe, it’s, you know, the physician in his capacity should be able to decide etc. etc. And a lot of feminists, actually including Ruth Bader Ginsburg, you know, have criticized Roe, saying rather than being decided on the right to privacy and rather than focusing on protecting the physician, ideally Roe should have been decided on the issue of gender discrimination. Only women get pregnant. Therefore only women are denied certain “benefits,” such as being able to participate in society, you know, because of unwanted child bearing.

Conclusion

Lisa: There’s still a stigma around having and talking about an abortion. There’s still a lot of assumptions out there about who gets abortions and who becomes an abortion advocate, what kind of people they are. In the 1960s Sherri Chessen confounded a lot of those expectations.

Leslie Reagan: I think what it does show us is, like, maybe the assumptions people have is these people are actually much more radical than they think. If they would look at their pictures, they see women dressed in early 1960s suits and pearls and things and might write them off. But they’re actually quite radical in talking about abortion. I mean, coming forward with something that is incredibly stigmatized.

Alexis: Sherri didn’t disappear after she got an abortion. She kept speaking out for all the other women who still needed them, and the experience changed her.

Sherri Chessen: At the time, I knew that I wasn’t going to get my way if I ranted and raved. But over the years, and if you were to meet me now, I think my anger built up. And when I see other people suffering, and in the same manner, and when I see mostly the male of the species deciding for us what we should do, I get, excuse the expression, pissed as hell. I do. I finally got angry.

Lisa: Dortha Biggs too, still speaks out about reproductive rights.

Dortha Biggs: I will do anything that I can to help. It’s important that others understand what some of us did to get rights. And it scares me to think that people who have never walked in our shoes and have never experienced this try to make decisions for us.

Lisa: Today, access to abortion is actually more vulnerable than it has been for decades. In 2019, 58 abortion restrictions were passed. The state of Alabama has banned it almost entirely. New restrictions are being proposed all the time.

Carole Joffe: I think one way to put all this together is to, you know, is to just show the sort of strange combination of, on one hand, the steady progression of women throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. And yet at the same time, you know, the backlash, you know, arguably it was a more in some respects, a more progressive period right around the time of Roe than it is now.

Alexis: Distillations is more than a podcast. We’re also a multimedia magazine.

Lisa: You can find our podcast videos and stories at distillations.org.

Alexis: And you can follow the Science History Institute on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Lisa: This episode was reported by Mariel Carr and produced by Mariel Carr and Rigo Hernandez.

Alexis: It was mixed by James Morrison.

Lisa: Also, there’s a lot more to Jane Hodgson’s story, but we couldn’t fit it all here. So we added a mini bonus episode just about her. Check it out in your feed!

Lisa: Special thanks to our colleague, historian of medicine Ashley Bowen, for bringing us this story. And thanks to Physicians for Reproductive Health, which gave us permission to use the oral history.

Alexis: For Distillations, I’m Alexis Pedrick.

Lisa: And I’m Lisa Berry Drago.

Alexis: Thanks for listening.