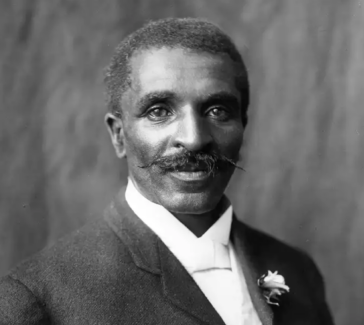

Francisco Hernández

The Spanish physician and natural historian led the first European state-sponsored scientific expedition to the Americas in the 1570s.

Francisco Hernández of Toledo (1515–1587) was a physician and natural historian in early imperial Spain. He is best known as the director of the first European state-sponsored scientific expedition to the Americas. From 1571 to 1577, he traveled throughout Mexico (then New Spain), collecting the region’s plants, animals, and history. His work reflects the nature of early imperial science: he sought not only to understand the natural world, but also to exploit it.

Scientific Expeditions to the Americas

By the late 1500s, Spain controlled much of the landmass that Europeans referred to as the “New World.” Yet the imperial government knew relatively little about the plants, animals, and people who lived in the territories they controlled. Spanish colonizers hoped that the plants and animals they encountered, so unusual in comparison to what they saw in Europe, would have economic value. Before they could profit from the land’s natural resources, though, they first needed to know what those natural resources were.

Hernández, a learned botanist and anatomist who had served as royal doctor since 1567, was ordered by King Phillip II to collect knowledge of the natural resources of Spain’s colonial territories, with a special focus on those that might have medicinal value. Upon his arrival in New Spain four years later, he would interview anyone who might have knowledge of the land’s resources. He went to gardens, markets, and hospitals to gather information about the physical characteristics of plants and their usage as medicines.

But Philip II did not want to rely on testimonials alone; rather, he instructed Hernández to conduct experiments to test the efficacy of these proposed treatments. Sometimes, Hernández resorted to testing the medicines on himself to meet the king’s demands. Hernández was also charged with collecting biological samples that could be brought back to Spain and with treating the sick during disease outbreaks. After completing this project in New Spain, he was instructed to travel to Peru and repeat the project there. By all accounts, it was a monumental task.

The Realities of Fieldwork

Hernández had a complicated relationship with the people he interviewed for this project. On one hand, he saw the value of Indigenous peoples’ knowledge. He believed that his final project should be organized according to linguistic categories that existed in Nahuatl, the dominant Indigenous language of central Mexico, because he believed that naturalistic knowledge was embedded in it. For instance, one term for a spiny tomato plant, “neixpopoaloni,” directly translates to “that which cleans the eyes,” suggesting medical usage. He also insisted upon translating his work into Nahuatl so that it could benefit the Indigenous population.

Unfortunately for Hernández, his relative closeness to Indigenous people, their cultures, and religions led the Spanish colonial forces—including the infamously intolerant Spanish Inquisition—to view him with suspicion. On the other hand, he frequently wrote disparaging comments about Indigenous people, especially when he believed that they were restricting his access to their knowledge:

CLASSROOM DISCUSSION

Historians can read the opinions that Hernández had of his guides and informants, but they have not found any opinions that those individuals wrote about Hernández. What might they have written about him? How might this biography, and broader historical understandings, be modified if those perspectives were written down and preserved?

Hernández originally believed that he could complete his project in five years. Upon arriving in New Spain, however, he realized that this was far too ambitious. His early letters to King Phillip II in 1572 pleaded for an extension of his trip. By 1575, however, Hernández changed his mind. Increasingly concerned that his manuscripts would be censored by the Inquisition if he sent them unaccompanied to Spain, he begged for the right to return and oversee their publication.

His deteriorating health also contributed to his desire to return to Spain, rather than continue his work in Peru. Nearly 60 years old and weakened by his self-experimentation, Hernández worried that he did not have the time or strength required to finish the expedition. He was especially concerned about the constant exposure to diseases that his work required. Many of these diseases were recently introduced to New Spain from infected Spanish conquerors and enslaved Africans. They had a large impact on vulnerable Indigenous communities, which had little biological immunity or previous medical knowledge of how to treat them. Yet nothing could prepare Hernández for the epidemic of cocoliztli that struck central Mexico the next year. Hernández wrote:

By 1577, many of the Indigenous people who had helped Hernández complete his project were now dead from this devastating disease. He set sail for Spain that year.

Hernández’s Legacy

Hernández returned with six volumes describing more than 3,000 plants, over 400 animals, 35 minerals, and 10 volumes of paintings. These manuscripts were never published in their entirety. Instead, in the years after he died from an unidentified chronic illness in Madrid, numerous books were published using selections from these manuscripts.

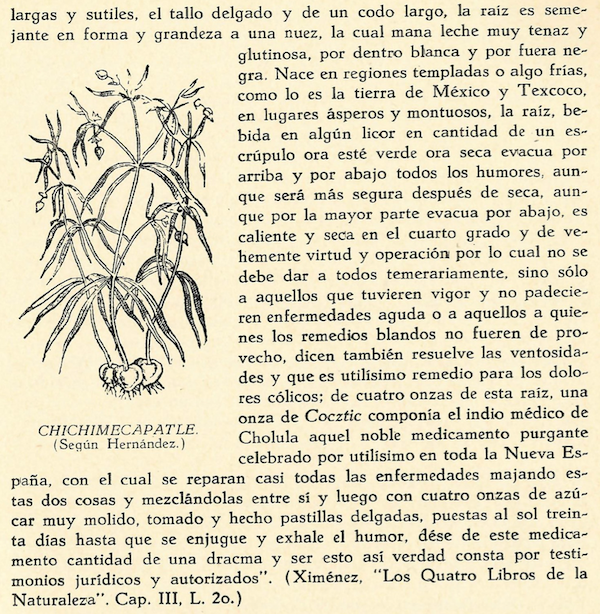

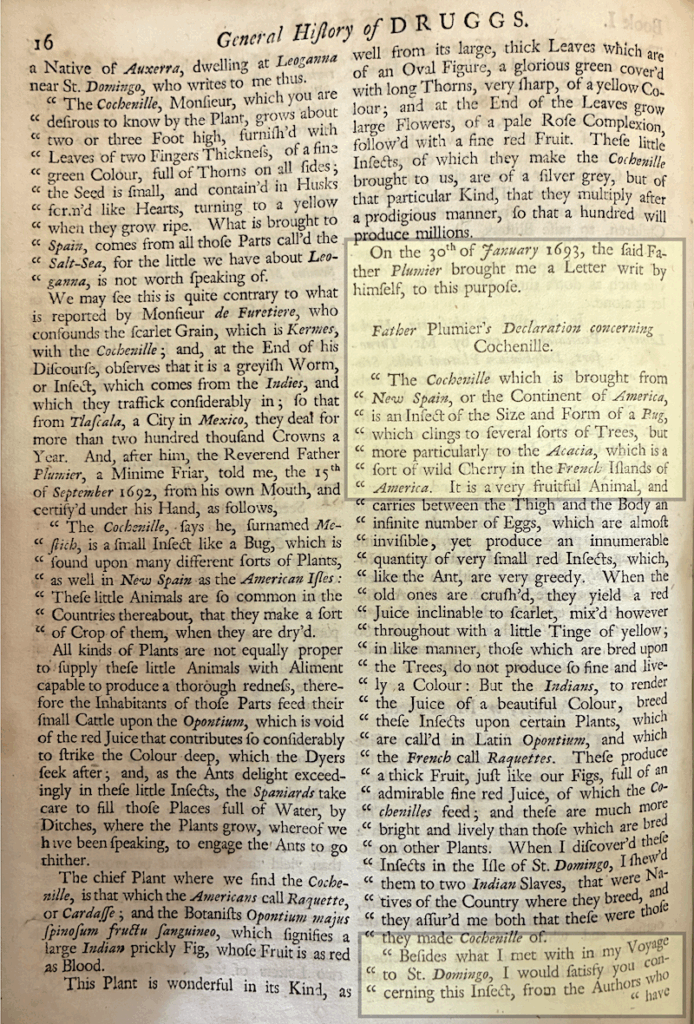

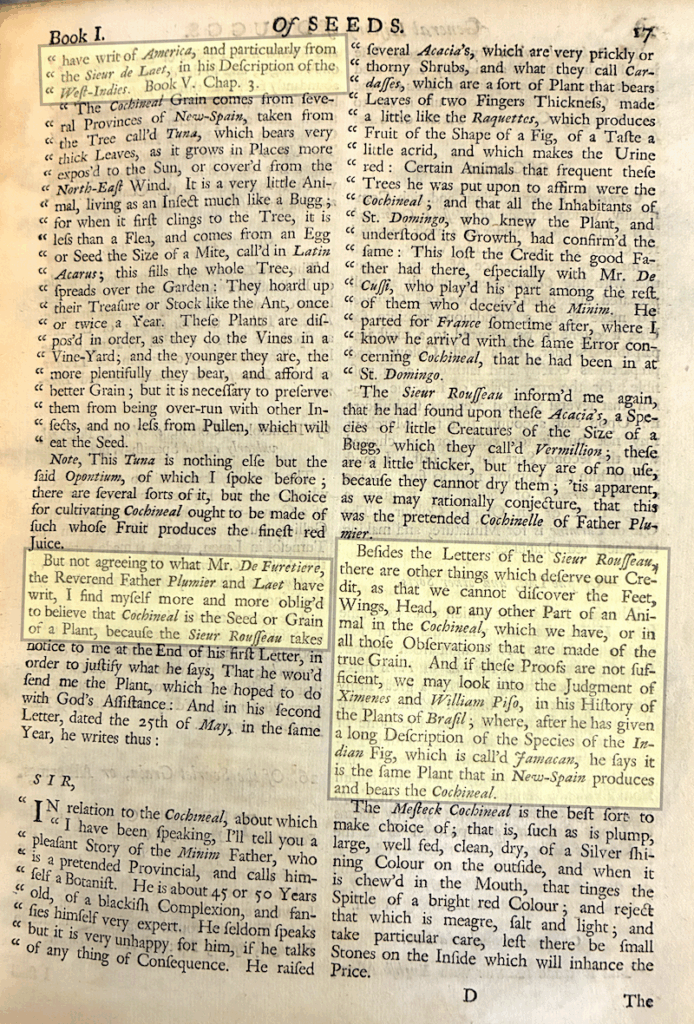

Some, like the Quatros libros (1615) by Friar Francisco Ximenez and Novus Orbis (1633) by Johannes de Laet, translated entire chapters of Hernandez’s manuscripts into Spanish, Dutch, Latin, and French. Translators occasionally added their own comments. Others, like the Rerum medicarum Novae Hispaniae thesaurus (1651) by an Italian scientific society, included not just text but also hundreds of illustrations. This task required careful creation of wood carvings based on each of Hernández’s paintings. With each translation into a new language, the words that Hernández wrote spread widely throughout Europe and the Americas. It is through these translations that historians can see Hernández’s influence on scientific fields, including medicine, zoology, and botany.

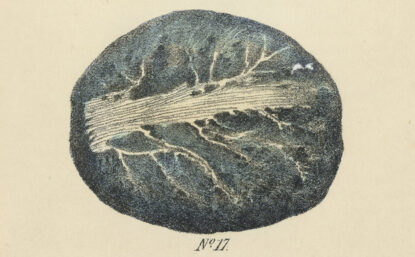

There is a sample of cochineal, a vibrant dye that Hernández collected alongside medicinal plants, on display in the Science History Institute Museum. Explore the museum’s permanent exhibition above to learn more about how cochineal relates to the broader history of textiles and dyes.

These editions of Hernández’s work accompanied a growing interest in collecting American plants and animals for European botanical gardens and cabinets of curiosity. Collectors believed that, in gathering and organizing “exotic” specimens from around the world, they would uncover more general principles that could explain the astounding diversity of life forms seen on Earth. Naturalists relied on these editions as authoritative descriptions of phenomena that they often had no chance to observe themselves. But details were often lost in translation. Rather than serving as a single foundation on which all naturalists agreed, the many editions of Hernández’s work—and the slight differences between them—fueled scientific debates for years to come.

LEARN MORE

One particularly intense debate in 17th-century Europe concerned the biological nature of cochineal, a vibrant red dye that was one of Spain’s most profitable exports from their American territories. Was it an insect or a seed? Examine the attached letter and the recipient’s response. Which translations did each writer cite? Which conclusions did each of them reach about the nature of cochineal? If you were alive at this time, how would you determine who was correct?

Pages 16 and 17 from the English translation of A General History of Drugs (1737) by Pierre Pomet.

Glossary of Terms

Natural history

A branch of biology that uses observational methods to study plants, animals, and other organisms.

Back to top

Spanish Inquisition (1478–1834)

A court system that surveilled, punished, and executed individuals suspected of being insufficiently or insincerely Catholic due to their Jewish, Muslim, Indigenous, and/or African ancestry/cultural practices. The Inquisition was active both in Spain and in its colonial territories.

Back to top

Imperial Spain

The historical period beginning in 1492 in which Spain colonized numerous parts of the world, especially the Americas but also parts of southeast Asia and north-central Africa. Although most colonies gained independence in the 1800s, this period did not officially end until 1976.

Back to top

Indigenous Peoples of the Americas

Communities who were already present in the Americas prior to European colonization, as well as their descendants. These communities are known in different countries as “First Nations,” “Native Americans,” or “Original Peoples (Pueblos Originarios).”

Back to top

Further Reading

Bleichmar, Daniela. (2021). New Worlds, New Texts. In A. Blair, N. Popper, & D. Bleichmar (Eds.), New Horizons for Early Modern European Scholarship (pp. 53-71). John Hopkins University Press.

Caraccioli, Mauro Jose. (2021). Writing the New World: The Politics of Natural History in the Early Spanish Empire. University Press of Florida.

Dumbarton Oaks, “Francisco Hernández’s Expedition.”

Hernández, Francisco. Quatro libros de la naturaleza y virtudes de las plantas y animales que estan receuidos en el uso de la medicina en la Nueva España [Four Books on the Nature and Virtues of Plants and Animals for Medicinal Purposes in New Spain]. Mexico: Diego López Dávalos, 1615.

Varey, Simon. (2000). The Mexican Treasury: The Writings of Dr. Francisco Hernández (R. Chabrán, C.L. Chamberlin, & S. Varey, Trans.). Stanford University Press.

Varey, Simon, Chabrán, Rafael and Weiner, Dora B. (Eds.) (2000). Searching for the Secrets of Nature: The Life and Works of Dr. Francisco Hernández. Stanford University Press.

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.

You might also like

SCIENTIFIC BIOGRAPHIES

Eizi Matuda

The Japanese Mexican botanist made extensive collections of Central and South American plants, aroids and cacti in particular.

COLLECTIONS BLOG

Natural Blues

In a world dominated by synthetic textile dyes, natural alternatives persist.

DIGITAL EXHIBITIONS

Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Poisonous Plants

Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories from 1887 to 1927 open a window to the history of medicine and empire.