Friedrich Mohs

The German mineralogist created the Mohs Hardness Scale, a simple tool for determining the hardness of minerals that is still used today.

A passion for mineralogy, order, and professional recognition shaped the career of Friedrich Mohs (1773–1839). Mohs’s research networks and his proximity to influential figures in politics and business made his career possible. His lasting contribution was a tool for the classification of minerals.

Early Life in the Mountains

Friedrich Mohs’s life began in the market town of Gernrode, on the northeastern edge of the Harz Mountains (located in the center of present-day Germany). It was a thriving mining area rich in silver-bearing galena and zinc blende. The eldest son of a wealthy merchant, Mohs yielded to family pressure and went to work in his father’s business as a young man.

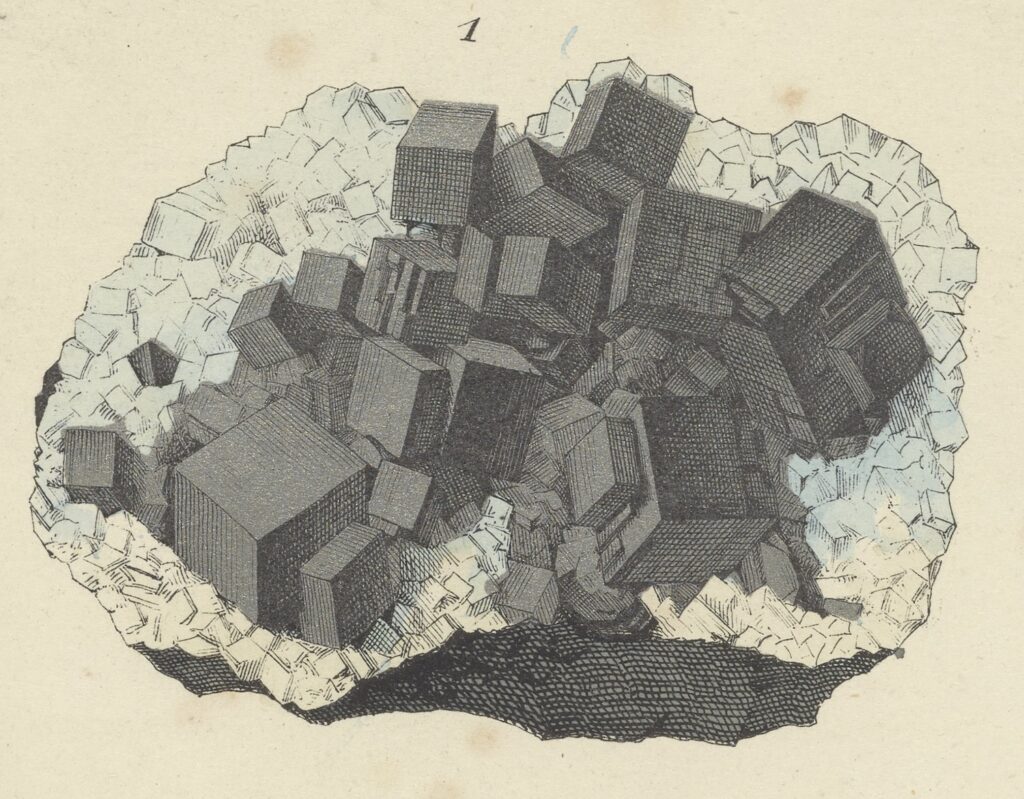

(Left) Undated galena specimen featured in the Institute’s Earthly Matters exhibition and (right) an illustration of galena from The Mineral Kingdom (1859).

But at 23, Mohs’s intellectual curiosity led him to study mathematics at the University of Halle in Prussia. Lecturers there addressed the mineral kingdom, which Mohs resolved to learn more about. After a year at Halle, Mohs left to further his education at the Freiberg Mining Academy, an internationally recognized training center for the mining industry where Abraham Gottlob Werner, the famous mineralogist, taught. At Freiberg, Mohs received practical training in mining and quarrying, and learned how to identify rocks.

Upon completing coursework in 1801, Mohs was offered a position as a “lower foreman,” supervising a section of a mine in Neudorf, near his hometown. He drew on his training at Freiberg and Werner’s mentorship to suggest ideas for modernizing the local mining industry. But these were not implemented, so Mohs resigned the position and returned to Freiberg in 1802.

LEARN MORE

Biographers have to be selective; they must decide which events in a life are relevant and which are not. They describe these events from distinct perspectives. In this biography, my approach examines the ways Mohs intervened and took control of his life. Mohs voluntarily left gainful employment twice (first in his father’s business and second as a foreman), so one might describe his life path—at least in this early phase—as self-determined. This self-determination was possible because of his wealth and privilege.

A System of Mineralogy

Freiberg attracted students of mineralogy from all over the world who forged lasting friendships and significant professional networks. Upon his return, Mohs met George Mitchell from Belfast and Robert Jameson from Edinburgh. They planned to establish an institute in Dublin modeled on the Freiberg Mining Academy and invited Mohs to help them develop these plans. In the course of their relationship, Mitchell drew Mohs’s attention to the world-famous mineral collection of the Viennese banker Jakob Friedrich van der Nüll. Van der Nüll was looking for an expert to catalog his collection, and Mohs, though still inexperienced, was given the opportunity.

An enthusiastic Mohs completed the task in one year. By 1804, he had published his findings in a three-part work. In this catalog and treatise, he expressed concerns about Werner’s approach to classification. Both Mohs and Werner were inspired by Carl Linnaeus’s method of botanical classification, which was based on external characteristics. But Mohs thought Werner’s approach was overly dependent on the internal characteristics of minerals and was therefore limited by the analytical chemistry of the time. Mohs, in contrast, prioritized accessible external characteristics such as color, form, brilliance, hardness, and specific gravity more exclusively.

LEARN MORE

At a time when the distinction between amateurs and professionals was still fluid, catalogs like the one Mohs wrote for van der Nüll were shared by private mineral collectors and specialists who we might think of as “scientists” today. They appeared in large numbers and offered guidance on classifying specimens from other collections. Can you think of other examples of books that help both scientists and the broader public identify and organize the world?

Mohs drew these interrelated characteristics into a new comprehensive system, one that was geographically broader and more diverse than Werner’s. He broadened the basis of his system through his travels and professional networks. Mohs’s catalog contained descriptions of each individual specimen, totalling 1,654 pages. He also previewed the new classification method he was beginning to develop, which related individual characteristics and specimens to his “true object of study,” namely, “the Earth itself.”

Envisioning the catalog as both a practical tool and a theoretical treatise, he subtitled it Uber die oryktognostische Klassifikation, nebst Versuch eines auf blosse aussere Kennzeichen gegriindeten Mineralsystems (A system based entirely on external characteristics, described and made useful as a handbook of oryctognosy with the addition of many explanatory notes and necessary corrections appropriate to the current state of mineralogy) [Vienna, 1804]. Intended as a “guide for beginners,” the work made Mohs famous immediately.

Alpine Minerals

Mohs made frequent trips to mines of the Habsburg territories and he wrote a study of the Villacher Alps in the southern part of Austria during the early 1800s. These trips broadened his horizons beyond the regions of Anhalt and Saxony, his previous areas of focus. During this time, his interest in classifying minerals grew, and the work prepared him for a position in the Habsburg monarchy. When Archduke Johann of Habsburg founded the Johanneum Museum in Graz in 1811, Mohs was invited to curate the mineral collection. A pioneering institution that became a model for other museums in the territories of the Habsburg monarchy, the Johanneum highlighted Styrian material culture. It demonstrated new methods of teaching with collections.

Mohs took the opportunity to expand his teaching materials and to test them in the classroom himself. He attracted around 30 students a year, including many prominent figures from Austria’s intellectual elite. In 1812, he published his Versuch einer Elementar-Methode zur naturhistorischen Bestimmung und Erkennung der Fossilien (Attempt at an Elementary Method for the Natural-historical Determination and Recognition of Fossils) in Graz, which introduced his new approach to classification, the Mohs Hardness Scale.

LEARN MORE

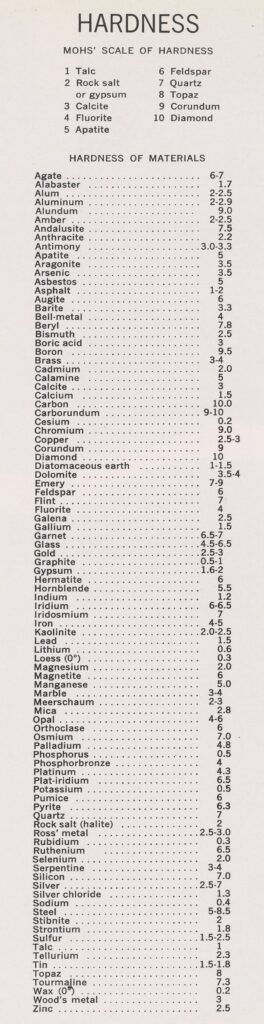

Although Mohs’s Hardness Scale was just a small part of his broader system of mineral classification, it was used widely, well into the 20th century. Mohs considered hardness to be one of the “physical properties” of minerals, those features that “neither depend upon their form . . . nor upon the presence or absence of light” (1825). Uniting such theoretical considerations with a practical test, he formalized degrees of hardness by scratching one mineral with another. Of the two minerals, “the harder one scratches the other, but cannot inversely be scratched by it.”

Using 10 reference minerals—talc, gypsum, calcite, fluorite, apatite, orthoclase, quartz, topaz, corundum, and diamond—he produced a relative scale with 10 ranks. Intermediate ranks were added in later years. Though the scale is widely known to lack precision, its enduring popularity reflects the overlapping mineralogical interests of scientists, industrialists, and collectors.

How does his scale compare to others you might have heard of, like the Richter Scale or even this test for sugar concentration?

For this, the press described Mohs as a “teacher who gives life to these dead masses,” “astute and ingenious”—in a word, he was “revered.” Contemporaries recognized him as the only person “capable of surpassing Werner.” Mohs continued to develop his system of mineral classification in Graz over the next five years.

Climbing the Academic Ladder

Mohs undertook a journey in 1817 to northern Germany and Great Britain, where he reconnected with some of his colleagues from Freiberg. In June of that year, Werner, his former professor, died in Dresden. Mohs stopped there as part of this tour and seized the opportunity to inform the members of the state body responsible for university hiring of his willingness to succeed Werner at the Freiberg Mining Academy. In doing so, he successfully presented himself at exactly the right moment, securing the position despite strong competition. Reflecting on this later in life, Mohs said that his decision to give up his position in Graz was only natural because succeeding Werner in Freiberg was, in his view, “the highest [position] he could achieve in the scientific field.”

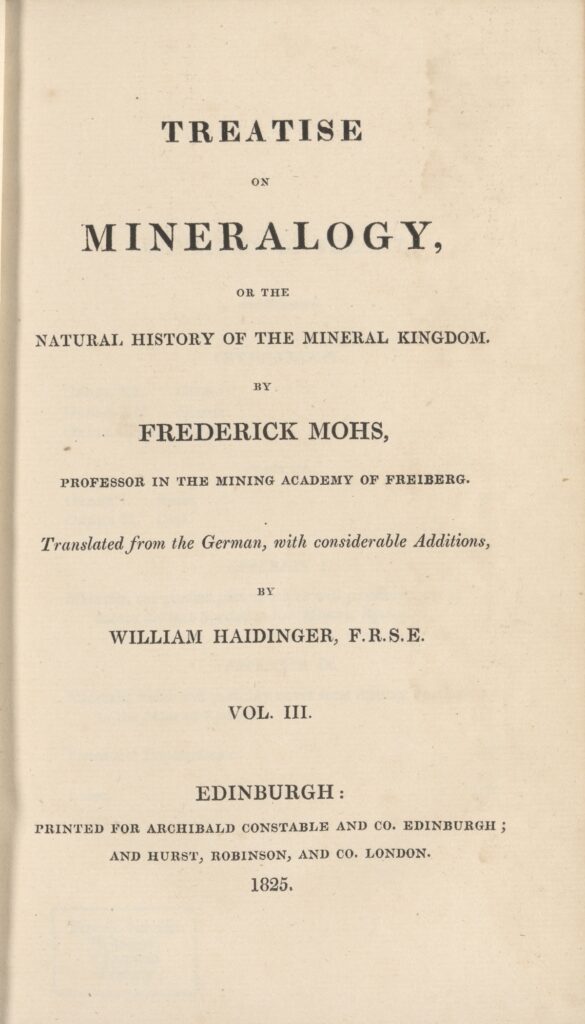

In Freiberg, Mohs further developed his method of mineral classification in Die Charaktere der Klassen, Ordnungen, Geschlechter, und Arten der naturhistorischen Mineral-Systems (The Characters of the Classes, Orders, Genera, and Species or, The Characteristic of the Natural History System of Mineralogy. Intended to Enable Student of Discriminate Minerals on Principles Similar to Those of Botany and Zoology), published in 1820. It was translated into English that same year. As Mohs later explained, he felt it was necessary to publish quickly to defend his claim to priority.

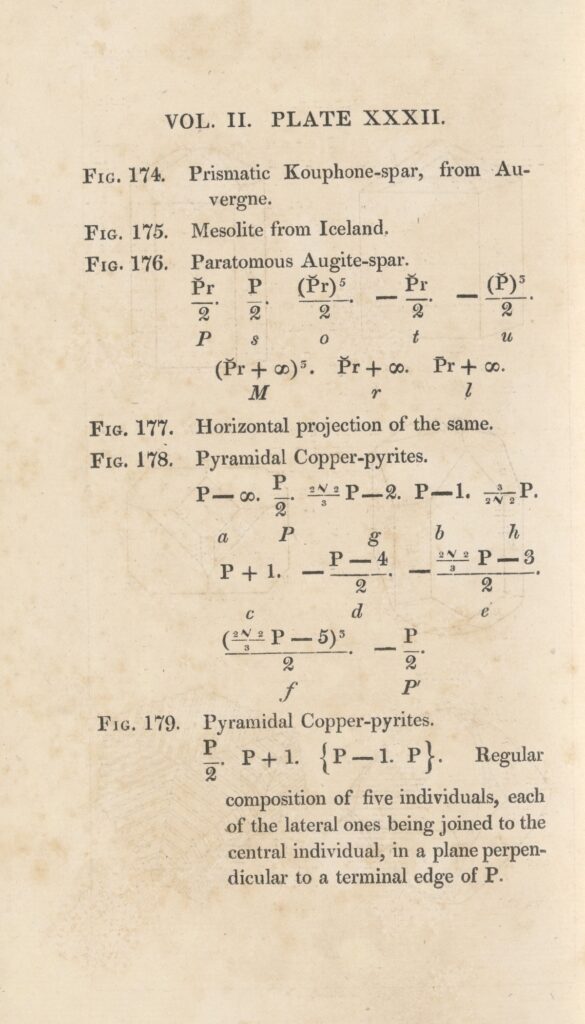

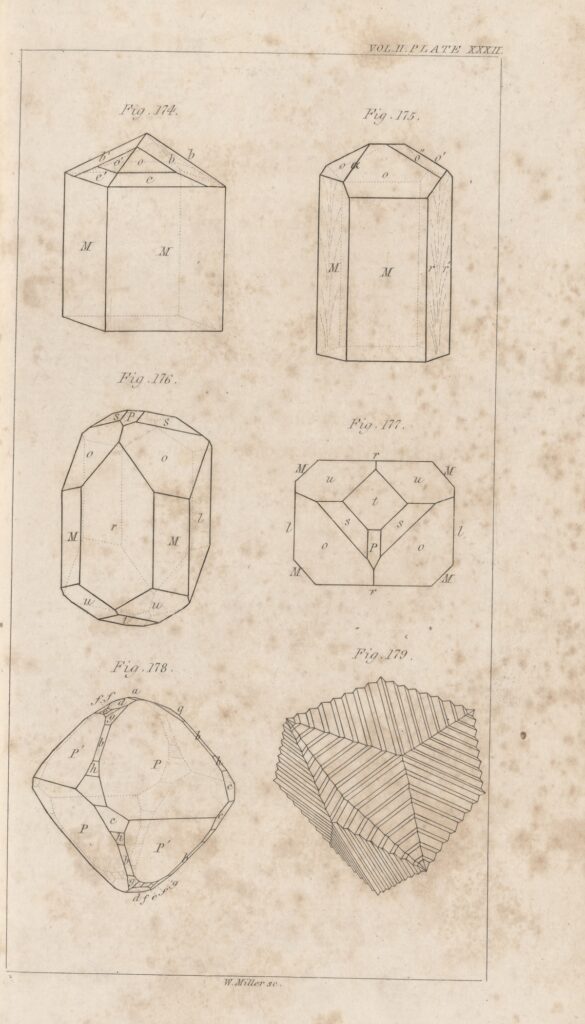

Mohs’s 1825 Treatise on Mineralogy offers a comprehensive description of his system.

Austrian Minerals

In July 1826, Friedrich Mohs received a royal decree from Emperor Francis I, declaring that he would take Mohs into his service as the first full professor of mineralogy at the University of Vienna. The opportunity to establish his method of mineral classification prominently in the imperial city and to communicate it directly to teaching staff throughout the monarchy convinced Mohs to give up his prestigious professorship at Frieberg. He also hoped it would inform the design of museums and requested access to the Vienna Court Mineral Cabinet accordingly. Emperor Francis I was in favor, as Mohs’s expertise would allow the Court Mineral Cabinet to easily adopt the latest display practices. For Mohs, the interaction between collections, research, and teaching was crucial. He considered it to be a guarantee of basic research and the fundamental value of mineralogy as a science.

The emperor also wanted Mohs to undertake exploratory trips to the provinces of the Austrian Empire and to act as an expert advisor on proposals for reform. Mohs thus became a state advisor on mineralogy, working across three institutions: the university, the court collection, and the mint and mining authority. His standing and influence increased considerably during his early years in Vienna.

But in 1835, Mohs left the Court Mineral Cabinet to resume work in the mines. In the final years of his life, the professor who had always presented himself as a theorist in his textbooks renewed his interest in practical mining. As Mining Councillor, he published Anleitung zum Schürfen (Guide to Mining) in 1842. With this book, he achieved the broad influence he had hoped to attain through teaching and the museum: it was distributed to every mining authority in the Austrian Empire.

Glossary of Terms

Oryctognosy

The study of all things dug up from the ground.

Back to top

Styria

A heavily forested and mountainous region (today, a state) in southeast Austria.

Back to top

Natural History

A branch of biology that uses observational methods to study plants, animals, and other organisms.

Back to top

Further Reading

Wilhelm Fuchs et al., Friedrich Mohs und sein Wirken in wissenschaftlicher Hinsicht. Ein biographischer Versuch. Wien: Frandel und Comp. 1848; included: Mohs’ Autobiography, p. 26-60.

Marianne Klemun, “Die Gestalt der Buchstaben, nicht das Lesen wurde gelehrt.” Friedrich Mohs’ “naturhistorische Methode” und der mineralogische Unterricht in Wien, in: Mensch, Wissenschaft, Magie: Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Wissenschaftsgeschichte (2004): 43-60.

Luzzini, Francesco. “Harvesting Underground: (Re)generative Theories and Vegetal Analogies in the Early Modern Debate on Mineral Ores.” Notes and Records of the Royal Society (2023).

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.

You might also like

EXHIBTIONS

Earthly Matters

Explore a unique collection of minerals that tells the story of human curiosity about the material world around us.

NEWS

New Mineral Exhibition Unveiled at Packed Opening Celebration

Ribbon cutting officially opens ‘Earthly Matters’ and brand-new gift shop.

DIGITAL COLLECTIONS

Earthly Matters Collection

View the 23 elements, crystals, gemstones, and precious metals featured in our ‘Earthly Matters’ exhibition.