Mary Letitia Caldwell

Caldwell’s lab at Columbia University helped launch the careers of several women in U.S. biochemistry during the early 20th century.

Mary L. Caldwell (1890–1972) became the first woman to hold a professorship at Columbia University in 1929. Over the course of her 40-year career there, she developed a vibrant research program focused on nutrition and biochemistry. She mentored several women chemists in her lab, helping to promote the study of amylase enzymes and opening up new professional opportunities for her students in industry and academia.

Education

Mary Letitia was born in Bogotá, Colombia, to Milton and Susannah Caldwell, Presbyterian missionaries from Ohio. Her family prioritized education, and Caldwell was supported in her studies just like her four brothers. All of the Caldwell children eventually received a college education and went on to noteworthy careers in academia and public service.

The family returned to the United States in time for Caldwell to attend high school in Greenfield, Ohio. She entered the Western College for Women (present-day Miami University) upon her graduation in 1909. Women’s colleges, or seminaries, were an important refuge for young women with interests in science at the time. Western had been created in 1855 by Presbyterian founders who sought to blend intellectual rigor with moral cultivation. The school promoted affordability and diversity through a “domestic system” in which students took care of daily chores alongside their coursework. Western’s science curriculum around 1900 was wide-ranging: it included courses in astronomy, geology, biology, physiology, botany, physics, chemistry, geometry, trigonometry, and domestic science. It also offered courses in such traditionally “male” subjects as Latin and Greek. Caldwell completed her undergraduate degree in 1913.

While many graduates of Western College went on to pursue missionary work, Caldwell remained on campus after receiving her degree. She became an instructor and taught chemistry at Western for an additional four years. But she soon realized that she wanted to pursue a research career beyond teaching. In 1918, she accepted a fellowship to begin graduate studies at Columbia University in New York. She completed her master’s degree the following year and earned her PhD in 1921 under the mentorship of Henry C. Sherman, a food chemist and nutritionist.

Enzymes

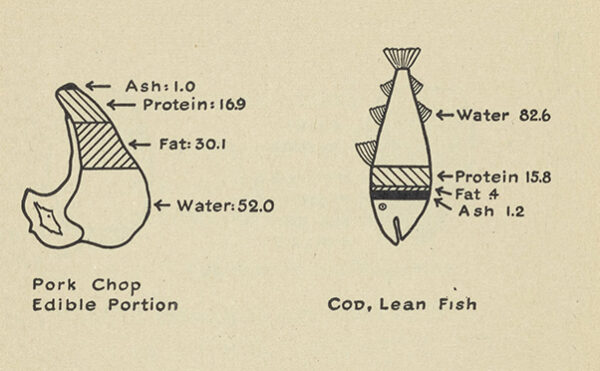

Caldwell’s dissertation, “An Experimental Study of Certain Basic Amino Acids,” investigated the processes by which enzymes from the pancreas break starches down into sugars. She wanted to know which compounds “activated” this process and which ones did not. It aligned with the broader goals of Sherman’s lab, which sought to promote human health and agricultural efficiency through precise understanding of the chemistry of life processes. Together, Caldwell and Sherman demonstrated that enzymes are essentially proteins, challenging the work of Nobel laureate Richard Willstätter.

A significant part of Caldwell’s dissertation involved the development of new methods for purifying the amino acids that were involved. At the time, researchers in her line of work often purchased commercially available samples for their experiments. But the impurity and scarcity of these materials prompted her to start preparing her own samples.

Caldwell’s preparation techniques would become one of her lasting contributions to biochemistry. She and her collaborators were the first to crystalize pancreatic amylase, which allowed for more precise measurements of its stability and activity. Her work shows that the development and standardization of tools and techniques is no less important than the discovery of new truths about nature in the history of chemistry.

Caldwell’s preparation techniques were later applied to other enzymes by laboratories across the U.S. and in Europe. Her generalized enzyme purification procedure was reportedly used by businesses for everything from wallpaper glue to the manufacture of prepared foods. Her published acknowledgments point to particularly close relationships with the Corn Industries Research Foundation and the Takamine Ferment Company.

Mentorship

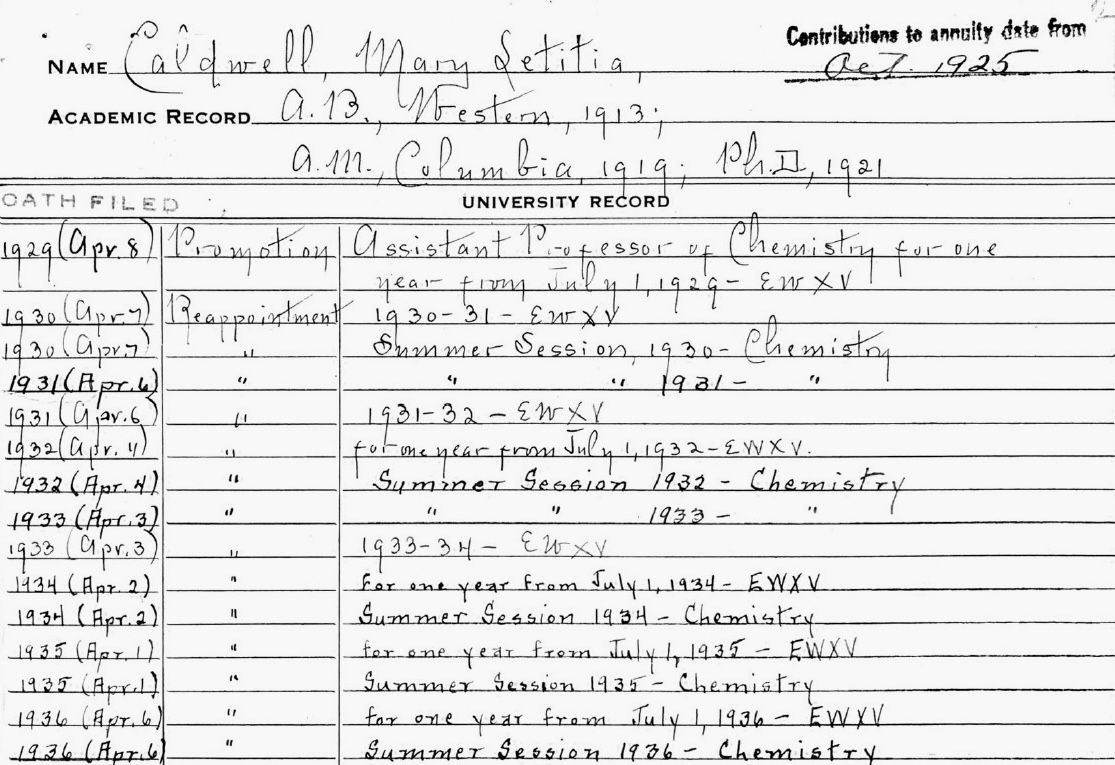

Caldwell was hired as an instructor of chemistry by Columbia as soon as she finished her PhD. She was reappointed on short-term contracts 13 times until 1929, when she was promoted to assistant professor. Becoming a professor was highly uncommon for women in the 1920s, and it was a distinct achievement. But in Caldwell’s case, it did not bring the professional security one might expect of the position today: she had to be reappointed on a year-by-year basis through 1938. Caldwell was promoted to associate professor in 1943 and finally achieved the rank of full professor in 1948, a prestigious title that she held until her retirement in 1959.

Caldwell faced an uphill battle to win respect in the role because of her sex. As Marie Maynard Daly, who was one of Caldwell’s advisees, recalled:

Daly’s account of her mentor also suggests that discrimination played a role in Caldwell’s day-to-day labor. Not only did she take on Sherman’s teaching load after he retired, she also served as graduate advisor and secretary to the department—several jobs rolled into one. She was responsible for mapping out students’ individualized courses of study, for assigning their teaching responsibilities, and for negotiating the financial details of their stipends and fellowships. Caldwell used the extra responsibility, however, to win support for the students in her lab, an unusually high percentage of which were women.

LEARN MORE

Caldwell mentored the PhD projects of 18 students during her career at Columbia, often publishing papers with them. Her publications can help us reconstruct her scientific network, which included numerous women chemists. Among her coauthors are Mildred Adams, Roslyn B. Alfin, Mary M. Becker, Lela E. Booher, Ruth M. Chester, Jane E. Dale, Marie M. Daly, Emma S. Dickey, Susan E. Doebbeling, Mary Eitingon, Virginia H. Gettler, Virginia M. Hamrahan, Florence M. Mindell, Mary Misko, Louise L. Phillips, Ildiko Radichevich, Gloria C. Toralballa, Marguerite G. Tyler, Gertrude W. Volz, and Ruth S. Weil.

The acknowledgements that Caldwell’s students wrote in their PhD theses characterize her lab as a supportive environment for women chemists. In her dissertation, “Study of the Action of Pancreatic Amylase on Waxy Maize Starch,” Florence Mindell expressed her “deep appreciation to Professor Mary L. Caldwell for suggesting the problem and for her advice during the course of the investigation. Without her aid and encouragement, it would have been impossible to undertake this research.”

Mindell also acknowledged other students in the lab, who thanked her in return, giving the sense that the Caldwell lab was a place of collaboration and mutual respect. This reinforces Daly’s recollection that “the high point” of Caldwell’s life came in 1960, when she was awarded the Garvan Medal by the American Chemical Society. This award, like Caldwell’s mentorship, has helped to uplift the contributions of women chemists since the 1930s.

Glossary of Terms

Seminary

Female seminaries were founded in the U.S. during the mid-1800s. They were intended to provide young women with a serious education and graduates often went on to careers in teaching.

Back to top

Enzyme

A kind of protein that can break down and change different types of molecules or ingredients.

Back to top

Further Reading

Columbia University Archives. “Mary Leticia Caldwell and Marie Maynard Daly.”

Daly, Marie M. 1976. “Mary Letitia Caldwell, 1890–1972,” in Wyndham D. Miles, Ed., American Chemists and Chemical Engineers. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society, 62–63.

Grinstein, Louise S., Rose K. Rose, and Miriam H. Rafailovich. 1993. Women in Chemistry and Physics: A Bibliographic Sourcebook. Westport, CN: Greenwood Press.

Sherman, H. C., Florence Walker, and Mary L. Caldwell. “Action of Enxymes upon Starches of Different Origin.” Journal of the American Chemical Society 41 (1919): 1123–1129.

Support

Support for this biography was made possible by the Wyncote Foundation.

You might also like

COLLECTIONS BLOG

Ladies Who Lab: Lesser-Known Women in Science, 1920–1970

Highlighting the work of 20th-century female scientists in our library collection.

STORIES BY TOPIC

Dig Deeper: Food Science

Interested in historical materials about food science? Explore our museum and library collections!

DISTILLATIONS PODCAST

Flemmie Kittrell and the Preschool Experiment

A 1960s home economist runs a radical experiment in her preschool laboratory—with big implications for millions of kids living in poverty.