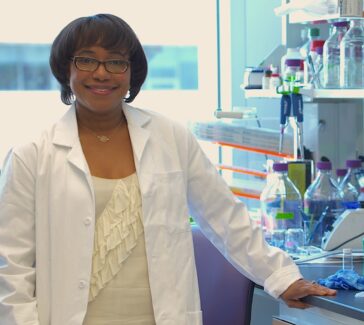

Uma Chowdhry

Polymer science and technology are just two of the areas to which Chowdhry, former chief science and technology officer at the DuPont Company, contributed.

An ambitious teenaged Uma Chowdhry (1947–2024) left her home in India to study physics and engineering in the United States. But after falling in love with chemistry, particularly materials science, the study of solids at the molecular level, Chowdhry decided to work in industrial research. She was fascinated by the possibility that her findings might end up in a practical application on the open market.

LEARN MORE

Biography is one way of learning about a person. Oral history is another. Spend a few minutes listening to Uma Chowdhry’s interview archived by the Science History Institute’s Center for Oral History. What do you hear? Has the recording picked up background noises, interesting accents, nervous laughter, or meaningful pauses? What might these tell you about the interview context, who is speaking, or how the speakers feel about the memories being discussed? What do think you can learn about Chowdhry from her oral history that is different from the content of this biography?

Dreaming the Impossible

Chowdhry was born in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, in 1947, the year her home country became independent from Great Britain. She first became interested in science in high school and studied physics at the University of Bombay, graduating with a bachelor’s of science degree in 1968.

She moved to the United States, hoping to study nuclear physics in graduate school, but two people got her hooked on chemistry: her future husband, chemist Vinay Chowdhry, and Pol Duwez, a materials chemist at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), where she was earning her master’s degree in engineering. After graduating from Caltech in 1970, she worked at the Ford Motor Company for a short time and then went on to earn a PhD in materials science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1976.

DuPont and Superconductors

The next year Chowdhry went to work at DuPont in their main labs in Wilmington, Delaware, where she became involved in many different research projects. One of the earliest studied better ways to make a compound called tetrahydrofuran, or THF, a common laboratory solvent used in industry.

Later she did research on ceramics—materials like porcelain and china that are chemically very similar to glass. Ceramics do not normally conduct electricity and, in fact, are often used as insulators in electrical gadgets. Chowdhry cleverly applied chemistry to make ceramics that conduct electricity; moreover, she was able to make ceramics that conduct electricity even better than metals do.

Such materials are called superconductors (materials that have no resistance to electrical current at temperatures near absolute zero), and they have many potential uses in computers, batteries, and other electrical devices. The technologies she contributed to at DuPont are now part of electronic packaging, photovoltaics, batteries, biofuel, and many sustainable products that fundamentally change the way we use everyday things.

Getting “Kicked Upstairs”

Eventually, Chowdhry was promoted into management at DuPont, although this had not been her career goal. Some chemists do not necessarily want to be “kicked upstairs,” preferring research to management. Chowdhry, however, soon found she not only loved her new work, but she was good at it too. She discovered in herself the characteristic that all good leaders have—the ability to inspire people to want to do their best.

For a while Chowdhry was head of DuPont’s Terathane operations. Terathane is a substance used to make various polymers, including polyurethanes. Most polyurethane molecules consist of alternating shorter chains of molecules—some very stiff and straight, others floppy and flexible—hooked together like cars in a train.

This arrangement allows the polyurethane to be strong yet flexible and not brittle. The floppy, flexible segments in polyurethane chains are Terathane molecules. Polyurethanes are used to make items as diverse as foam seat cushions, paints, and skateboard wheels.

Polymer science and technology are just two of the areas to which Uma Chowdhry contributed. For Chowdhry, a leader in both research and business, it was not enough to make a new material that she was proud of as a scientific accomplishment; she also had to find practical uses for it. She focused on moving new chemicals from beakers in the lab to products in the store.

In 2006 Chowdhry became DuPont’s chief science and technology officer, a position from which she retired in 2010, after 33 years with the company. She was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 1996 and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2003.