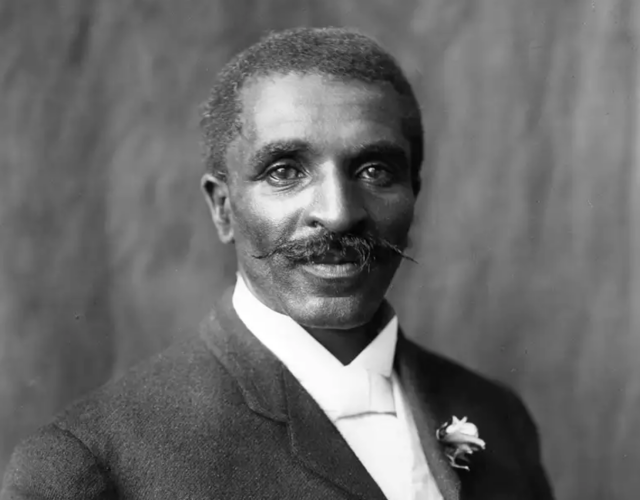

George Washington Carver

Known to many as the Peanut Man, Carver developed new products from underappreciated Southern agricultural crops and taught poor farmers how to improve soil productivity.

In the post–Civil War South, one man made it his mission to use agricultural chemistry and scientific methodology to improve the lives of impoverished farmers.

George Washington Carver (ca. 1864–1943) was born enslaved in Missouri at the time of the Civil War. His exact birth date and year are unknown, and reported dates range between 1860 and 1865. He was orphaned as an infant, and, with the war bringing an end to slavery, he grew up a free child, albeit on the farm of his mother’s former master, Moses Carver. The Carvers raised George and gave him their surname. Early on he developed a keen interest in plants, collecting specimens in the woods on the farm.

Education

At age 11, Carver left home to pursue an education in the nearby town of Neosho. He was taken in by an African American couple, Mariah and Andrew Watkins, for whom he did odd jobs while attending school for the first time. Disappointed in the school in Neosho, Carver eventually left for Kansas, where for several years he supported himself through a variety of occupations and added to his education in a piecemeal fashion.

He eventually earned a high school diploma in his twenties, but he soon found that opportunities to attend college for young black men in Kansas were nonexistent. So in the late 1880s Carver relocated again, this time to Iowa, where he met the Milhollands, a white couple who encouraged him to enroll in college.

Carver briefly attended Simpson College in Indianola, studying music and art. When a teacher there learned of his interest in botany, she encouraged him to transfer to Iowa State Agricultural College (now Iowa State University), dissuading him from his original dream of becoming an artist. Carver earned his bachelor’s degree in agricultural science from Iowa State in 1894 and a master’s in 1896. While there he demonstrated a talent for identifying and treating plant diseases.

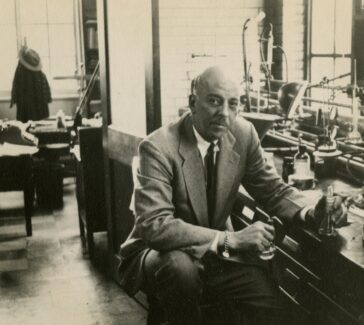

Tuskegee

Around this time Booker T. Washington was looking to establish an agricultural department and research facility at his Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama. Washington, the leading black statesman of the day, and two others had founded the institute in 1881 as a new vocational school for African Americans, and the institute had steadily grown.

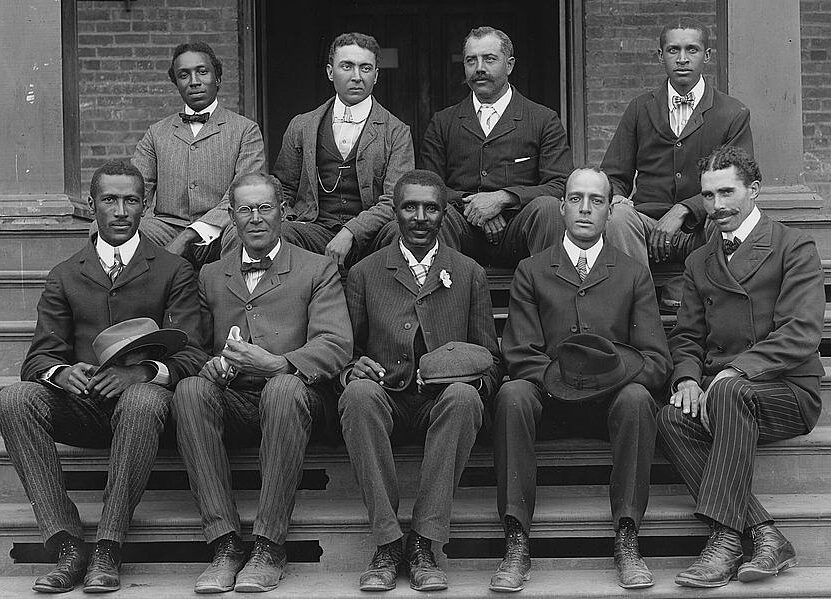

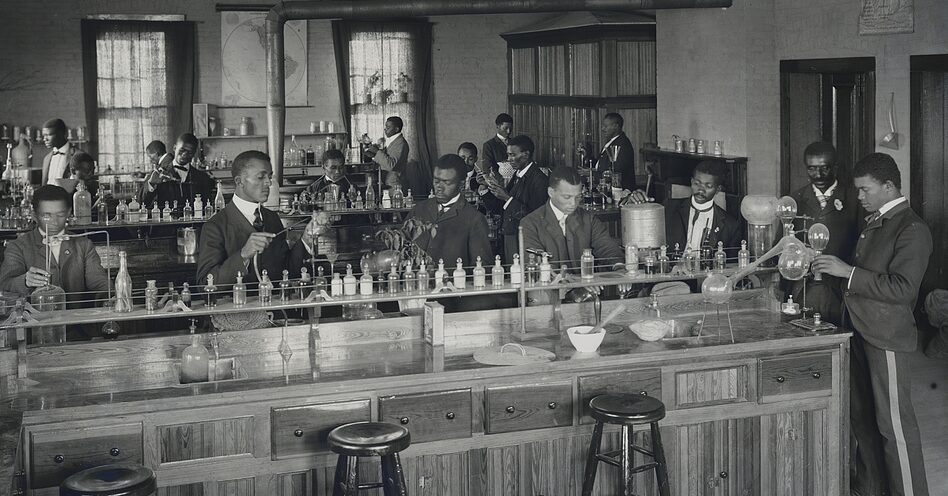

As Carver was the only African American in the nation with an advanced degree in scientific agriculture, Washington sought him out. Carver joined the faculty of Tuskegee in 1896 and stayed there the rest of his life. He was both a teacher and a prolific researcher, heading up the institute’s Agricultural Experiment Station.

Crop Rotation

Carver’s primary interest was in using chemistry and scientific methodology to improve the lives of impoverished farmers in southeastern Alabama. To that end he conducted soil studies to determine what crops would grow best in the region and found that the local soil was perfect for growing peanuts and sweet potatoes. He also taught farmers about fertilization and crop rotation as methods for increasing soil productivity. The primary crop in the South was cotton, which severely depleted soil nutrients, but by rotating crops—alternating cotton with soil-enriching crops like legumes and sweet potatoes—farmers could ultimately increase their cotton yield for a plot of land. And crop rotation was cheaper than commercial fertilization. But what to do with all the sweet potatoes and peanuts? At the time, not many people ate them, and there weren’t many other uses for these crops.

New Uses for “Undesirable” Crops

Carver went to work to invent new food, industrial, and commercial products—including flour, sugar, vinegar, cosmetic products, paint, and ink—from these “lowly” plants. From peanuts alone he developed hundreds of new products, thus creating a market for this inexpensive, soil-enriching legume. In 1921 Carver famously spoke before the House Ways and Means Committee on behalf of the nascent peanut industry to secure tariff protection and was thereafter known as the Peanut Man.

When he first arrived at Tuskegee in 1896, the peanut was not even a recognized U.S. crop; by 1940 it had become one of the six leading crops in the nation and the second cash crop in the South (after cotton). Both peanuts and sweet potatoes were slowly incorporated into Southern cooking, and today the peanut especially is ubiquitous in the American diet.

Carver also developed traveling schools and other outreach programs to educate farmers. He published popular bulletins, distributed to farmers for free, that reported on his research at the Agricultural Experiment Station and its applications.

Recognition

Through chemistry and conviction Carver revolutionized Southern agriculture and raised the standard of living of his fellow man. In addition to the popular honor of being one of the most recognized names in African American history, Carver received the 1923 Spingarn Medal and was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. The George Washington Carver National Monument was the first national monument dedicated to a black American and the first to a nonpresident.