Despite what you’ve heard, neuroscience’s most famous patient did not turn into a lying, drunken psychopath. He’s actually an amazing example of resiliency and overcoming trauma.

About The Disappearing Spoon

The Science History Institute has teamed up with New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean to bring a second history of science podcast to our listeners. The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Audio Engineer: Jonathan Pfeffer

Transcript

It was a lovely September day in 1848. A construction foreman named Phineas Gage was helping lay track for a railroad company in Vermont. Some boulders were blocking the railroad’s path, so the company hired a gang of rowdy Irishmen to blast their way through.

As foreman, Gage supervised the Irishmen. He also helped drill holes into the boulders and fill them with gunpowder. Gage then packed the gunpowder down into the hole with an iron rod. The rod looked like a short javelin. It was 1¼ inches thick, stretched 3 ½ feet long, and weighed 13 pounds.

Around 4:30pm, the Irishmen were loading some busted rock onto a cart. It was near quitting time, so perhaps they were a-whooping and a-hollering. Gage had just finished pouring gunpowder into a hole, and turned his head.

Accounts differ about what happened next. Some say that Gage was packing the gunpowder down with the iron rod, and scraped it against the side of the hole, creating a spark. Regardless, a spark shot out somewhere inside the hole and ignited the gunpowder. At which point the iron rod reversed thrusters.

The iron rod blasted upward, and entered Gage’s skull below his left cheekbone. It destroyed a molar, pierced his left eye, and plowed into his brain’s left frontal lobe. The rod then exited on top, and landed twenty-five yards distant. One report claimed it whistled as it flew, and was streaked with blood.

The rod’s momentum threw Gage backward. He landed hard. Amazingly, though, he never lost consciousness. He twitched a few times on the ground, but was talking within minutes. He even walked under his own power to a nearby cart, and sat upright on the trip back to town.

At his hotel, Gage waited in a chair on the porch and chatted with passersby—who were, uh, startled to see a volcano of bone jutting out of his scalp.

Thus began perhaps the most famous case in medical history. Every neuroscience textbook in existence has a section on Phineas Gage. Incredibly, though, nearly every textbook gets the story wrong.

You might have heard that, after his injury, Gage became a criminal, a drunk, a psychopath. None of that’s true.

Instead, there’s good evidence that, far from turning toward the dark side, Gage recovered after his accident—and perhaps resumed something like a normal life. It’s a possibility that, if true, could transform our understanding of the brain’s ability to heal.

***

When the first doctor arrived, Phineas Gage greeted him by angling his head and saying, “Here’s business enough for you.” Finally, around 6pm, the first doctor turned the case over to Dr. John Harlow. It’s not clear why. Harlow was a country doctor. He mostly treated people who’d fallen off horses. Not neurological cases.

Harlow didn’t believe Gage’s story at first. Surely, the rod hadn’t passed through his skull? But it had: Gage had a flap in his cheek and everything. Harlow then watched Gage lumber upstairs to his hotel room and lie on the bed. Which ruined the linens, since his upper body was one big bloody mess.

In the room, Harlow shaved Gage’s scalp and peeled off the dried blood and brains. Harlow then extracted skull fragments from the wound. Throughout this all, Gage vomited every twenty minutes. But otherwise, he remained calm and lucid. He betrayed no discomfort or pain.

Over the next few days, an infection set in and Gage’s brain swelled dangerously. Things were touch and go for a week, and Gage lapsed into a coma. A local cabinetmaker measured him for a coffin.

But Harlow’s diligent care allowed Gage to pull through. Gage soon returned to his family farm on Potato Road to recover. Gage did lose his left eye, but his memory, language, and motor skills remained intact. All in all, he seemed almost normal.

Almost. Harlow had kept Gage alive, but Gage’s family swore that he’d changed. The man who returned home was not the same man they knew and loved. His memory, language, and motor skills remained intact. But his personality changed.

Before the accident, Gage was known for making plans and sticking to them. Afterward, he changed his mind willy-nilly and rarely stuck things through. Before, Gage was also indifferent to animals. Afterward, Gage adored critters of all kinds. And while the original Gage was courteous and polite in company, the new Gage was coarse and foul-mouthed.

Most strikingly, Gage lost all money sense and developed irrationally strong attachments to certain objects. Harlow once tested Gage by offering him money for some random pebbles that Gage had picked out of a stream. Gage refused to part with them even for $1,000. Gage also carried with him at all times the iron rod that had brained him.

Harlow summed up Gage’s new personality by saying that, quote, the “balance … between his intellectual faculties and his animal propensities seems to have been destroyed.” More pithily, friends said that Gage “was no longer Gage.”

Despite his stellar work record before, the railroad refused to reinstate Gage as foreman. He took to working odd jobs on farms instead. He also indulged his newfound love of horses and became a carriage driver in New Hampshire. At one point, Gage even exhibited himself at P.T. Barnum’s freakshow museum in New York, staring back at the audience with his one good eye. For an extra dime skeptics could part his hair and watch his brain pulsate through a flap of skin over the exit wound in his skull.

After his stint at the museum, Gage’s life gets murky for a few years. Facts are hard to come by. But that hasn’t stopped scientists from filling that vacuum of facts with rumors and unfounded speculation.

One rumor claimed that Gage developed a drinking problem and started getting into brawls at taverns. Another claimed that he became a scam artist. He supposedly went to a medical school and sold them the exclusive rights to keep and study his skull after he died. Then he went to another medical school—and sold the same rights. And then another school, and another, skipping town and pocketing the cash each time. One ridiculous source even claimed that Gage lived for a dozen years with the iron rod still impaled in his noggin.

Other rumors in modern textbooks contradict each other. Some sources describe Gage as sexually indifferent, while others call him promiscuous. Some sources say he was hot-tempered, while others call him emotionally void, as if lobotomized. One neuroscientist even claimed that Gage “had lost his soul.”

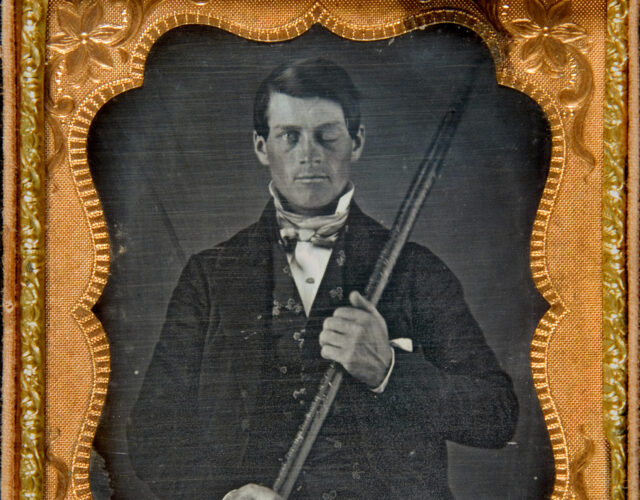

To be clear, there’s zero historical evidence for any of those rumors of Gage’s mental or physical decline. In fact, in the only known picture of Gage, he looks nothing like a wastrel or someone whose life is spiraling out of control. He’s proud, well-dressed, even handsome.

To be clear, Harlow’s reports make it clear that Gage’s personality changed somehow. It’s about the only hard fact we have, neurologically speaking. But his other comments about Gage’s mental state are ambiguous.

Take the comment about Gage’s life being taken over by “animal propensities.” That sounds dramatic, but what does that mean—“animal propensities”? Did he eat too much? Demand sex? Howl at the moon? We have no idea.

Or consider this. In addition to loving animals after his accident, Gage also felt drawn to children suddenly. And on his visits home, Gage would reportedly spin wild tales for his nieces and nephews. Made-up stories about his supposed adventures on the road.

Some neuroscientists have interpreted Gage’s storytelling as evidence of confabulation. It’s a neurological symptom that involves chronic lying. It usually arises after frontal lobe damage. Then again, who hasn’t made up a tall tale to make little kids laugh? They love that stuff. It’s a pretty weak case for brain damage.

Similarly, we know that Gage had trouble sticking to plans after his accident. That’s another sign of frontal-lobe damage, because the frontal lobe controls mental skills like reasoning, planning, and self-control. In addition, Gage seemed to lose the impulse control that prevents most people from swearing in public. But it’s a far cry from someone saying saucy words like “hell” and “damn” to claiming that Gage was a drunken, brawling criminal.

In all, Gage’s life story, as appears in textbooks, has become as much legend as fact—a mélange of scientific prejudice, artistic license, and outright fabrication. Most people who learn about Gage in classes or textbooks have no idea how weak the case is for Gage becoming a villain.

Moreover, some modern historians have argued, forcefully, that Gage seems to have recovered some of his faculties in the decade after his accident. He never became the Phineas Gage of old. But some of his negative traits either diminished or disappeared, possibly because his brain proved plastic enough to heal and recover some lost functions.

***

In 1852, Phineas Gage’s life took a dramatic turn. He left the New England of his youth and followed a gold rush down to Chile in South America. He was seasick the whole voyage. Once ashore, he found work driving a horse carriage. His job involved shuttling passengers along the rugged, mountainous trails between Valparaiso and Santiago.

Gage held this job for seven years. Which is staggering, considering both his brain damage, and the complexity of the work. Gage likely drove a team of six horses. And horse reins at the time were complicated because you had to control each horse separately.

For instance, consider rounding a bend. To do so without tipping the coach over, you had to slow down the inner three horses a touch more than the outer three horses, simply by tugging on their reins with varying amounts of pressure. That would have taken a lot of dexterity. I mean, imagine driving a car while steering all four wheels independently. This could not have been easy for someone with brain damage.

Especially because the trails in Chile were quite crowded. This would have forced Gage to make quick stops and dodge other carriages. And because he probably drove at night sometimes, he would have had to memorize the trail’s twists and turns and fatal drop-offs. Plus keep an eye out for bandits.

Gage also likely cared for his horses by grooming and feeding them—a significant responsibility. And, contradicting the claim that he lacked all money sense, Gage probably collected passenger fares. Not to mention that he presumably picked up some conversational Spanish while in Chile—no mean feat for any adult.

You wonder how many of Gage’s passengers would have climbed aboard had they known about their one-eyed driver’s little accident a few years earlier. But all in all, Gage seems to have handled himself fine.

It probably helped Gage that he followed a similar routine each day. He likely arose before dawn to prepare his horses and carriage. Then he spent the next thirteen hours driving the same road back and forth from Valparaiso to Santiago.

Now, the fact that Gage seemingly carved out a life for himself in Chile doesn’t mean that his brain recovered fully. But scientists now know that the brain’s neural circuits can recover somewhat after damage, partly by rewiring themselves. And perhaps Gage retained enough of his frontal lobes to retain some basic planning skills. At the very least, Gage didn’t deteriorate into the drunken sociopath that many modern textbooks claim.

In truth, those claims about Gage are probably influenced by modern cases of brain damage. Cases where people did turn into sociopaths. You can hear more in a bonus episode at patreon.com/disappearingspoon. People who gambled money wildly, abandoning their family, and suddenly become pedophiles. That’s patreon.com/disappearingspoon.

Sadly, despite building a life for himself in Chile, Gage couldn’t outrun his brain damage entirely. And when it did catch up to him, the end was swift.

Poor health forced Gage to leave Chile in 1859. He caught a steamer up to San Francisco, where his family had moved. After a few months of rest in California, Gage found work on a farm and seemed to be doing better.

Unfortunately, a punishing day of plowing in early 1860 wiped him out. He had a seizure the next night over dinner. More seizures followed.

Gamely, Gage tried to keep working during this spell of trouble. But after years of steady work in South America, the seizures made him restless and capricious again. He began drifting from farm to farm, quitting each job for unknown reasons.

Finally, on May 20th, 1860, while resting at his mother’s home, he had several violent seizures in a row. He died the next day at age thirty-six, having survived his accident by almost a dozen years.

Gage’s skull was later exhumed by doctors. It remains on display at Harvard University today, along with the iron rod that remodeled his brain. Oddly, his skull has become something of a pilgrimage spot for people with an interest in macabre history.

I’ve spent a lot of time in this podcast bemoaning the lack of hard facts about Gage’s life. But in truth, that dearth of details probably secured Gage’s fame. That lack left infinite room for interpretation, and allowed each generation of scientists to reinterpret his case anew. Everyone from legendary neurosurgeons to phrenologists reading head bumps have invoked Gage to support their pet theories. Overall, Gage has become a Rorschach blot for neuroscientists. What we think of him changes from era to era, as the obsessions and preoccupations of each era change.

Including our era. Nowadays scientists cite Gage in support of theories about multiple intelligences; emotional intelligence; the social nature of the self; brain connectivity; every modern neuro-obsession.

And what Phineas Gage means now will probably change in the future, too. In fact, Gage’s story will probably always be with us. In part because it’s a hell of a story! Once upon a time, a man with a funny name really did survive having an iron rod explode through his skull. It’s tragic, gruesome, bewildering—and even comes with a science lesson.

But the deeper reason that Gage will always be with us is this. Despite all that remains murky and obscure, his life can teach us something important—that the brain and mind are one. After all, about the only hard fact we know is that his personality did change. And that’s no small thing.

As one neuroscientist has written, “beneath the tall tales and fish stories, a basic truth embedded in Gage’s story has played a tremendous role in shaping modern neuroscience: that the brain is the physical manifestation of the personality and sense of self.” That’s a profound idea, and it was Phineas Gage who first pointed us toward that truth.