When Charles Dickens published Bleak House in the early 1850s, he included a scene where a character spontaneously combusts. Readers loved it, but one of Dickens’s good friends—a former scientist turned literary critic—blasted Dickens for including such a scientifically ignorant scene. But Dickens refused to back down, igniting one of the strangest controversies in literary history.

About The Disappearing Spoon

Hosted by New York Times best-selling author Sam Kean, The Disappearing Spoon tells little-known stories from our scientific past—from the shocking way the smallpox vaccine was transported around the world to why we don’t have a birth control pill for men. These topsy-turvy science tales, some of which have never made it into history books, are surprisingly powerful and insightful.

Credits

Host: Sam Kean

Senior Producer: Mariel Carr

Producer: Rigoberto Hernandez

Associate Producer: Sarah Kaplan

Audio Engineer: Rowhome Productions

Transcript

Before I start, a content warning: this episode contains some gruesome descriptions of death. And now, on with the show…

The first thing they noticed was the smell—like someone frying rancid lamb chops.

The two men sat in their flat in London and chatted uneasily about their midnight appointment with old Mr. Krook, whose shop was downstairs. But ominous sights and smells kept interrupting them. Black soot swirled around the room like the devil’s dandruff. It stained one man’s sleeves. And when the other man leaned on the windowsill, his hands came away streaked with yellow grease. “Give me some water!” he cried, “or I’ll cut off my hands.”

Midnight finally struck, and they descended the stairs. Mr. Krook’s shop was crammed with bottles, rags, and other hoarded trash. Walking through it was unpleasant even in the daytime. That night, they sensed something positively evil. They clung to each other as they crept along.

Krook lived in the back of the shop, and outside his bedroom door, a black cat leapt out and hissed. When they entered Krook’s room, the odor choked them. Grease stained the walls and ceilings as if painted on.

They squinted and saw Krook’s coat and cap on a chair. A bottle of gin sat on the table. But the only sign of life was the cat, still hissing. They swung their lantern around, searching for Krook.

They finally spied a pile of ash on the floor. They stared stupidly for a moment—before turning and running. They burst into the street and shouted help!,help! But it was too late. Old Mr. Krook was gone—a victim of spontaneous combustion.

Charles Dickens penned this scene in December 1852—an excerpt from his novel Bleak House. And most readers swallowed the story completely. After all, Dickens wrote realistic stories, and he took great pains to render scientific matters accurately. His observations on smallpox and neurological disorders are as acute as any doctor’s. So even though Krook was fictional, the public trusted that Dickens had portrayed spontaneous combustion with precision.

But a few readers heard about Krook’s death and began burning up themselves—in rage. Scientists then were laboring to debunk old nonsense like clairvoyance, mesmerism, and the idea that people sometimes burst into flames for no reason. And recent discoveries about heat and metabolism had provided strong support for their views. They proved that the human body, far from being removed from nature, was subject to strict laws.

But enough mysteries remained for old wives’ tales to flourish about things like spontaneous combustion. This only made both sides more desperate to prove their case. And within two weeks of Dickens publishing this chapter, skeptics began challenging him in print—igniting one of the strangest controversies in literary history.

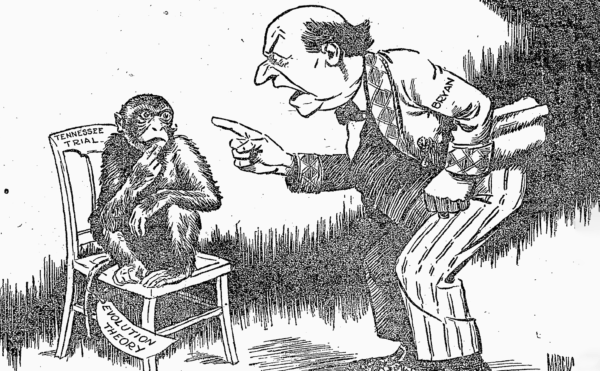

The man who led the charge against Dickens and spontaneous combustion was George Lewes. Lewes came from a line of actors and had a foot in the literary world. He was a critic and playwright, and was novelist George Eliot’s longtime lover.

Later in life, Lewes would pioneer the study of the unconscious mind. He also studied physiology as a young man, so he understood the body well. And he served as a sort of Victorian Richard Dawkins—always ready to attack superstition.

Lewes first met Dickens at age twenty; Dickens was five years older. They ran in the same circles, and they once acted together onstage in a benefit for a Shakespeare theater. Lewes played a part from Merry Wives of Windsor. Overall, Lewes counted Dickens as a friend.

Not that you’d know that from Lewes’s response to Bleak House. After reading about Mr. Krook’s death via spontaneous combustion, Lewes began fuming and wrote a column attacking the chapter.

In it, he acknowledged that artists have a license to bend the truth. But he protested that they can’t just ignore laws of physics. As he wrote, “The[se] circumstances are beyond the limits of acceptable fiction, and give credence to a scientific impossibility.” He furthermore accused Dickens of cheap sensationalism and of, quote, “giving currency to a vulgar error.”

Dickens was miffed. He always had an ambivalent relationship with science. He couldn’t deny the marvels that science wrought. He also had famous scientists for friends, like anatomist Richard Owen and the pioneering computer scientist Charles Babbage. Both formed the basis for characters in his books.

But Dickens was fundamentally romantic at heart.

He thought that science killed imagination and undermined Christian society. He detested the growing dependence on data and reductionism as well.

So when Lewes attacked Dickens, Dickens swung right back. He published Bleak House serially, as installments in a monthly magazine. So he had time to slip a rebuttal to Lewes into the January issue.

The novel’s action picks up with the inquest into Krook’s death. And the narration mocks critics of spontaneous combustion as eggheads too blind to see plain evidence. As Dickens wrote, “Some of these authorities (of course the wisest) hold … that the deceased had no business to die in the alleged manner.” To them, “going out of the world by any such by-way [was] wholly unjustifiable and personally offensive.”

But according to Dickens, common sense eventually triumphs. The coroner in the story declares, “These are mysteries we can’t account for!”

In letters to Lewes, Dickens continued his campaign. He claimed to have looked into the matter as thoroughly as a judge would have, and found thirty cases overall. He leaned especially hard on the case of an Italian countess who combusted in 1731.

The woman reportedly bathed in spirits of wine infused with camphor, possibly for her skin. The morning after one bath, her maid walked into her room to find the bed unslept on. As with Mr. Krook, soot hung suspended in the countess’s chamber, along with a yellow haze of oil.

The maid found the countess’s legs—just her legs—standing several feet from the bed. A pile of ashes sat between them, along with three fingers and her skull. Nothing else seemed amiss, except for two candles: the tallow had melted, but the cotton wick lay there unburned. A priest had recorded this tale, so Dickens considered it trustworthy.

Nor was he the only author to believe in spontaneous combustion. Mark Twain, Washington Irving, and Herman Melville all had characters combust as well.

Melville’s depiction was especially vivid. In it, two sailors drag a shipmate onto a boat. The man is dead drunk, and they leave him to sleep it off. A while later, they smell something foul—a dead rat, they fear. In hunting the odor down, they’re led back to the drunk sailor.

All of a sudden, the man erupts in fire. Melville describes how his “cadaverous face was crawled over by a swarm of wormlike flames”—flames that are a lurid green. The man also has a white tattoo that shimmers beneath the green blaze.

These literary scenes have certain elements in common. They usually involve old, sedentary alcoholics. Dickens’s Mr. Krook drank gin by the barrel.

During the actual combustion, people were consumed alarmingly quickly. Their torsos always burned completely, but their extremities sometimes survived. Eeriest of all, beyond the occasional scorch mark somewhere, the flames never consumed anything but the victims’ bodies. Afterward, foul odors and choking fumes pervaded the scene, along with soot and yellow grease.

The scenes are similar in part because the authors drew on the same sources for their material—magazine stories, medical accounts, and legal texts. According to such authorities, gin was the booze most likely to produce spontaneous burning, followed by brandy and whiskey. Rum, for some reason, was safer.

Preachers also used spontaneous combustion to rail against the evils of drinking. After all, can you imagine a more vivid depiction of hellfire than someone’s body going up in flames?

Believe it or not, Dickens and these other authors had some science backing them up here. Dickens wrote Bleak House within a decade of the discovery of nitroglycerin—an explosive oil that can indeed detonate spontaneously.

More significantly, spontaneous combustion seemed linked with one of the most important discoveries in medical history, involving the deep connections between combustion, blood, and breathing.

In 1628 the English doctor William Harvey provided the first modern evidence that blood flows around the body in a circuit, with the heart acting as a pump. Most people before this assumed that the liver converted food into blood and that our organs “drank” blood like plants do water.

At the same time, Harvey got some things wrong. He knew that both blood and air passed through the lungs, but he insisted that the two didn’t mix there. Instead, he thought the lungs merely cooled the blood by waving back and forth, like a fan. He insisted that the lungs didn’t alter blood chemically.

Later, in the 1660s, two other scientists proved that idea wrong. They showed this through a series of blood-curdling experiments.

These involved dissection, and using a bellows as an artificial lung. They observed that the organs seemed to function as long as air streamed through the lungs. From this, they concluded that the motion of the lungs meant nothing.Instead, we now know the lungs trigger chemical changes in the blood.

Then, chemists in the late 1700s got more specific. They determined that the lungs took in oxygen, which dissolves into the blood. The blood simultaneously released carbon dioxide, with the lungs expel.

When oxygen enters the blood, it slips inside red blood cells and latches onto hemoglobin molecules. Blood cells then carry that gas to tissues inside the body.

At that same time, the late 1700s, chemists were also investigating the role of oxygen in fire. They determined that oxygen is vital for combustion. Oxygen supplies the energy that makes fires burn. And they realized that oxygen might play a similar role in the body during metabolism.

To be sure, these scientists didn’t get everything right. They believed that the combustion of metabolism took place in the lungs. Blood then merely carried that energy to the cells. Not until the 1870s did they realize that that’s mistaken. Cells and tissues actually burn oxygen inside themselves—that’s where combustion-metabolism takes place.

Still, by the mid-1800s, scientists had the overall idea right. Our lungs take in oxygen for fuel. And the burning of that fuel induces a sort of slow combustion—a constant burning—inside us.

And Dickens and others argued, if slow fires were perpetually burning inside us, why couldn’t they suddenly flare up sometimes?

Scientists had proved that low fires were constantly burning inside us. And, maybe the fires flared up sometimes.

Such flare-ups seemed especially likely in alcoholics, whose very organs were dripping with gin or brandy. As for what sets off a spontaneous fire, perhaps fevers did, or raging hot tempers. Overall, in defending spontaneous combustion, Dickens was throwing more fuel onto a smoldering scientific debate. As one historian noted, “It was an exciting and confusing period. Lurid sensationalists as well as serious scientists [both] wrote about spontaneous human combustion” and took the matter seriously.

George Lewes, however—the Richard Dawkins of his day—was having none of this. Again, Dickens had cited historical sources that mentioned spontaneous combustion. But Lewes dismissed Dickens’s sources as, quote, “humorous but not convincing.”

Lewes noted that several were over a century old. He also pointed out that none of the accounts were written by eyewitnesses. The author had always heard the story secondhand from a cousin’s friend or a landlord’s brother-in-law. It didn’t help that Dickens had also cited the support of a celebrity doctor who promoted phrenology as well.

Most damning of all, Lewes cited evidence against spontaneous combustion from recent experiments in physiology. These experiments revealed that the liver metabolizes booze and breaks it down. As a result, our organs aren’t soaking in flammable substances.

More evidence came from Justus von Liebig. I’ve mentioned Liebig before on the podcast—the German chemist who tried to make artificial breast milk, the so-called deadly soup for babies.

Liebig cast doubt on spontaneous combustions by pointing out that our bodies are something like 75 percent water—far too wet to burn. Liebig even ran experiments where he tried to burn cadaver organs. They wouldn’t ignite without external fuel. As Lewes gleefully pointed out to Dickens, this undermines the whole premise of spontaneous human combustion.

Not surprisingly, Dickens dug in his heels and again cited those historical cases. Unfortunately, Dickens didn’t seem to grasp that eyewitness accounts about spontaneous combustion and scientific experiments on spontaneous combustion were not equally reliable evidence. As a result, he continued to insist on the reality of humans suddenly lighting on fire.

This wasn’t all stubbornness, though. It reflected a fundamentally different view of what science should mean to humans. As one critic put it, for Dickens, empirical science “merely corroborates what the heart already knows.”

Artistically, too, Dickens considered the scene in Bleak House with Mr. Krook burning up to be central to the novel’s theme. The story involves a ruinous court case that “consumes” the lives and fortunes of everyone involved. Krook’s death was a potent symbol of that, and Dickens couldn’t stand his metaphor being picked apart.

And the more defensive Dickens got, the more disgusted Lewes felt. They continued to bicker for ten months, until the final magazine installment of Bleak House appeared in September 1853. After that, when the novel appeared in book form, Lewes begged Dickens to put a notice in the preface, admitting the error. The very idea offended Dickens. Eventually, both disgusted, they mutually dropped the matter.

History of course has judged Lewes the winner here. Outside of supermarket tabloids, no human being has ever spontaneously combusted. And while there are some mysterious modern cases of human beings burning up, there are far more likely explanations—however morbid.

In every known case, open flames were burning near the person. Also, a flammable liquid like alcohol was often on hand. In all likelihood, the person died of a stroke or heart attack and simply caught fire. The parts of the body left behind were spared because they lack fat and may not have been covered with clothing which is often flammable.

But these realizations require modern understanding. Back in Dickens’s time, the idea wasn’t quite as ridiculous as it seems now. One medical text was still discussing spontaneous combustion as late as 1928.

Plus, Dickens was undeniably right about one thing: that in human affairs, spontaneous combustion can happen. Friendships and reputations can ignite instantly and consume themselves in smoke and ashes. Dickens and Lewes eventually patched things up, but for those ten months in London in 1853 the fires of resentment and umbrage burned awfully hot.